From spoons to semiconductors — we are what we make

Fired up: Anna Ploszajski gets to grips with the art of glass-making in her quest to fuse scientific theory and creative practice.

Handmade: A Scientist’s Search for Meaning through Making

Anna Ploszajski (2021)

2 July 2021 – Over the last 20+ years I have pursued a very eclectic conference schedule that covers 18+ technology and journalism events (my team covers another 8+ events) that has provided me perspective and a holistic tech education. You can see our “pre-COVID” annual conference schedule by clicking here. Our schedule is extensive. Call it my personal “Theory of Everything”. Although if you are not careful you can find yourself going through a mental miasma with all this overwhelming information.

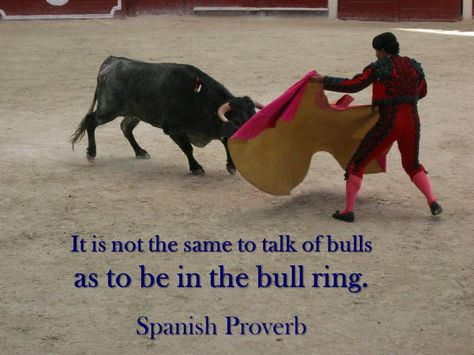

But much of this technology I have taken on board not only in my day-to-day operations, but to improve my writing, which can only be done by doing it. I take the old Spanish proverb to heart:

Because writing about technology is not just “technical writing.” It is about framing a concept, about creating a narrative, understanding perspective. So you need to “do the tech”. As a result I have been to Ukraine, courtesy of a long-time cyber security vendor, to see Russia’s “information warfare” campaigns in action, to meet and speak with experts on the front lines of those campaigns to see the nuts & bolts; I’ve been to Arina’s hands-on workshops/training sessions in Zurich to do digital analytics, extraction and decryption, forensics, and red team security testing; I’ve been to the IBM Research program in Haifa, Israel to do Project Debater, the system that can engage with humans in debating competitions, so I can understand how AI does “argument mining” and how it recognizes the statistical regularities of language. Oh, and a whole lot more hands-on adventures.

So when Bloomsbury sent out Anna Ploszajski’s new book for review (part of the publishers’ consortium in which I am a member) I pretty much dropped everything and read it in one day.

Anna is a materials scientist who took up science communication. But she found that the more she discussed her research with others, the less she could answer their questions. She knew all about the molecular interactions that give materials their strength, flexibility or hardness, but she couldn’t tell her friends and family about the best alternative to plastic, or why phone screens are made from glass even though it’s prone to smashing. To address these gaps in her knowledge, she got hands-on, exploring how artisans interact with substances that she knew only in theory.

In Handmade, Ploszajski investigates ten materials. She starts with the classic categories of her field: glass, plastic, metals such as steel and brass, and ceramics. She then moves on to materials common in making and crafts, and less often considered in the laboratory: sugar, wool, wood, paper and stone. She tries glass-blowing, pottery, steel casting, knitting and spoon carving; learns about plastic art, trumpet-making and stonemasonry; and gains a holistic perspective on objects to which she had never given a second thought. The efforts bring an understanding of the properties and cultural impact of materials that helps her to communicate more clearly. As a doer, I related deeply to her search.

Medicine: Discovery through doing

Ploszajski intersperses her experiences with the materials-science view of these media, from the amorphous molecular structure of glass to the chemical reactions between calcium minerals, moisture and carbon dioxide that give lime mortar its remarkable self-healing properties. She describes the history of each material’s use, with snippets of tradition and archaeology from around the globe — ranging from 3,000-year-old ancient Egyptian knitted socks to wind-operated furnaces in Iron Age Sri Lanka. And she offers anecdotes about what the materials have meant to her: her immigrant grandfather’s plastics-manufacturing business; the sugary snacks that got her through a swim across the English Channel; how paper, relaying thoughts and stories written by lesbians of centuries past, helped her to grasp her own sexuality. The result is fascinating and affecting.

Real-world impact

In the chapter “Steel”, she describes how, as an undergraduate, she won a place on a team building a vehicle to tackle a land-speed record. She worked out that cogs in the car’s engine were breaking under stress owing to carbon atoms clumping inside the metal. But, lacking the confidence to share her ideas with the older, male mechanics, she was unable to apply the understanding in a practical way that could help the team to reach its goal.

This disconnect between doing good science and presenting it in the way that people need has become all too obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers can understand the mechanisms of infection, produce effective vaccines and report compelling epidemiological data. Yet without an appreciation of why people cannot or will not take vaccines, the findings might not help people.

Spoons that Ploszajski carved as she explored the medium of wood

Ploszajski’s experiences also shine light on how people shape research. Scientists aim for objectivity, but often forget that their experiences and culture affect every aspect of their work. Just as the grain of a piece of wood dictates the shape of the spoon that Ploszajski carves, the structure of a society dictates the research questions that scholars pursue. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; trouble arrives when researchers forget that their approaches are shaped by their circumstances. Similarly, Ploszajski, a trumpet player since childhood, learns with surprise that the instruments are not always made of brass; some players prefer the sound produced by silver or copper. This put me in mind of how astronomy is usually considered a visual science — but some blind astronomers have pioneered investigating the cosmos through sound.

Regular readers will recall my piece about Wanda Diaz Merced, a blind astronomer who says that converting astronomical data into sound could bring discoveries that conventional techniques miss. Astronomy is inextricably associated with spectacular images and visualizations of the cosmos. In 1933, for example, U.S. physicist Karl Jansky reported detecting the first radio waves from space, as an audible hiss in his antenna. He moved toward more sound analysis. But at some point, visualization came to dominate the way we interpret astrophysical data. It was in 2005, at NASA, that Robert Candey created a prototype data analysis tool that would familiarize blind people with space-physics data. With advances in AI, software was developed that could map astronomical data into sound — its pitch, rhythm and volume. People were able to identify signals that were masked by noise by using vision only, by combining visual interaction and sound, and by using audio only. Researchers found that when you combine audio with visual interaction, your sensitivity to the signal improves.

I did wish for more from Ploszajski’s accounts. Directed mainly at lay readers, the book’s scientific explanations stopped just as I began to be intrigued. And she only scratches the surface of the history, cultural connotations and potential uses of each material. I almost wished for a volume based on each chapter, an encyclopedia of science and craft.

It’s enlightening to reflect on how our physical experience affects our thoughts. And, as Ploszajski points out:

“It’s unhealthy to compartmentalize: each can improve the other”.

I am not a crafter although in Greece I do grow grapes, raise goats and make cheese. So, in a way, I do understand the comfort Ploszajski finds in finding something magical about spinning disparate, fragile fibres into warm, strong yarn, or coaxing solid cheese curds out of liquid milk.

After a day of thought and theory, it’s delightful to hold something real in one’s hand and say “I made that” or “I grew that”.