Part of my large writing project this summer about the ultimate opposition, the big binary kahuna: Life and Death. But vis-a-vis technology, which infiltrates all culture. I stumbled across the idea while reading a memento mori art book, plus the works of Maël Renouard and Kathleen Wallace on technology and the fluid self.

Based on my readings to date, the first known appearances of a suite of modern human innovations relating to technology, social organization, symbolism and exploitation of the landscape and resources occurred in Africa during the Middle Stone Age period.

In Kenya, the earliest evidence of deliberate human burial in Africa. The discovery of the burial of a young child in a cave around 78,000 years ago sheds new light on the role of symbolism in the treatment of the dead during the Middle Stone Age.

22 June 2021 – The discovery of the burial of a young child in a cave in Kenya around 78,000 years ago sheds new light on the role of symbolism in the treatment of the dead during the Middle Stone Age. Much of the current debate surrounding the location and timing of the emergence of modern human behavior focuses on Africa during the Middle Stone Age (MSA), which lasted from about 320,000 to 30,000 years ago.

The first known appearances of a suite of modern human innovations relating to technology, social organization, symbolism and exploitation of the landscape and resources occurred in Africa during this period. This time frame is also associated with the earliest known hominin fossils placed in the modern human lineage. The emergence of more-complex behaviors surrounding the treatment of the dead is often framed in the broader context of an increase in symbolic capabilities.

Writing in Nature Magazine, María Martinón-Torres, Francesco d’Errico, and Michael D. Petraglia¹ present a convincing case for the intentional burial of a young child in eastern Africa, at Panga ya Saidi, a cave in Kenya (see figure below). The authors’ meticulous recording of this archaeological evidence has revealed the earliest known human burial in Africa.

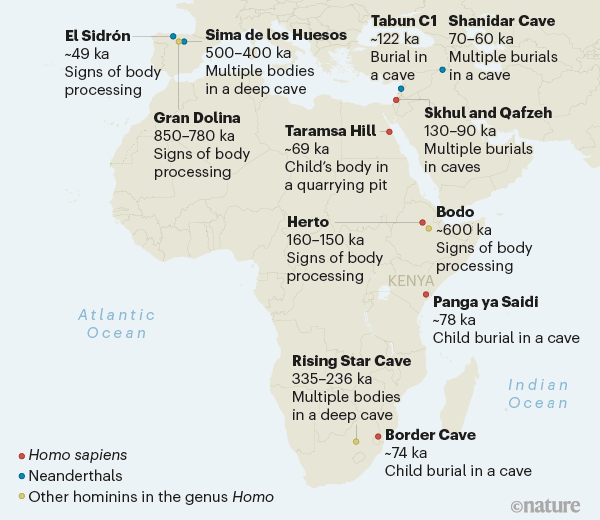

Above: archaeological sites where treatments of the dead have been found.

A range of behaviors are associated with ancient handling of the dead, which include body processing (sometimes associated with cannibalism), placement of a body in a relatively inaccessible location (such as a deep cave) or signs of a deliberate burial. Some sites at which such behaviors have been identified are linked to Homo sapiens and to other closely related species (other hominins belonging to the genus Homo). The authors report the excavation of a child’s grave at Panga ya Saidi in Kenya dated to around 78,000 years ago (78 ka), which is the earliest known human burial in Africa. The fossils at El Sidrón, Sima de los Huesos, Tabun C1 and Shanidar Cave are those of Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis); those at Gran Dolina are Homo antecessor; the cranium at Bodo is Homo heidelbergensis or Homo rhodesiensis; and the fossils at Rising Star Cave are Homo naledi.

The child, estimated to have been around three years old, seems to have been carefully arranged in a deliberately excavated pit and then covered by sediment scooped up from the cave floor. Microscopic features of the bone structure and the chemical composition of the sediment surrounding the bones reveal that the body was fresh when it was buried, and decomposed in the grave. The arrangement of the surviving bone fragments reveals that the child was placed lying gently inclined on their right side, with their legs folded and drawn up towards their chest.

Several anatomical connections between adjacent bones have survived, which suggests that the body was covered quickly after burial. A gradual trickle of sediment from above the corpse presumably prevented the bones from collapsing into the empty spaces that would have otherwise formed during the putrefaction of the soft tissues. An exception to this was the cranium and three neck bones, which collapsed into a void thought to have been created by the decay of a perishable head support. The right clavicle (one of the bones of the shoulder girdle) and two ribs had rotated in the grave, which might imply that part of the upper body was originally tightly wrapped in a perishable material.

The burial pit and the archaeological layers surrounding it and directly above it are associated with MSA stone tools, securely anchoring the burial in the MSA. The authors date the burial itself to 78,300 ± 4,100 years ago.

And some bits of the tech involved. The date was obtained using probabilistic modelling and a technique called optically stimulated luminescence to determine the age of the entire sequence of the assessed archaeological layers.

In addition, equally fascinating is the remodelling process, using traditional two-dimensional (2D) techniques, plus the visualization and analysis of bone using high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) techniques to improve the understanding of bone biology and biological anthropology, which I touch upon in this post. Much has been learned regarding the biological information encrypted in the histomorphology of bone, yielding a wealth of information relating to skeletal structure and function, as well as structure and the chemical composition of the sediment surrounding buried bones.

This finding demonstrates that humans in East Africa were deliberately burying their dead at least 78,000 years ago. Archaeological and fossil records reveal a wide spectrum of mortuary treatments carried out by early humans (species in the genus Homo) spanning at least 800,000 years or so. The first step towards understanding the nature of these mortuary behaviours — the actions and beliefs surrounding the treatment of the dead — is to reconstruct the series of human actions associated with the deposition of a body.

A major component of geoarchaeology is the reconstruction of paleoenvironments at archaeological sites or within a region. Paleoenvironmental information can be essential for understanding the environment before, during, and after site occupation, and it may provide insights into environmental changes that influenced technology, social structure, human subsistence, and settlement strategies. I’ll return to this topic later this summer when I am back in Greece and I can continue my summer program on geoarchaeology at the University of Crete, cut-short last year due to COVID.

Not all mortuary behaviors leave traces that are archaeologically visible. The importance of a burial is that it documents a sequence of planned and deliberate actions involving: the creation of an artificial space to contain the body; the placement of a body or body parts into that space; and the covering of the body, often using the sediment that was removed during preparation of the grave. Each of these stages can, but might not always, leave visible archaeological traces, so not all burials will be recognized as such. Other actions that leave enduring traces in the archaeological record relate to processing of the corpse, and might involve the removal of soft tissues, separation of body parts, or signs of cooking or chewing indicative of cannibalism. Examples have been found in the archaeological record of human bones that have been shaped into tools and used as decorative objects.

The second step towards understanding these mortuary behaviors is to infer whether there was any meaning associated with the treatment of the dead beyond the practical measures required to avoid attracting animal scavengers to spaces used by the living and to prevent contamination of those spaces during decay of the body. Strictly functional interventions might also include disarticulation of the body to facilitate transportation, nutritional cannibalism, or the opportunistic use of bones or teeth as tools or as a raw material for manufacturing an object. Inferring signs of symbolic behaviour in burials is one of the more contentious areas of archaeology.

Behaviors that might point towards a departure from purely practical motivations and towards a more meaningful treatment of the dead are those that involve an investment of time and resources beyond what is strictly required to dispose of or make use of the corpse. Such actions include careful placement of the corpse in the grave to achieve a desired body position or orientation, the wrapping or binding of the body for reasons other than to aid transportation, or the deliberate incorporation of items of value in the grave. Such items include objects that could reasonably be considered to have a personal or decorative significance, and those linked to the social role of the deceased. The interred objects might also encompass articles thought to be needed by the deceased in another existence, such as food or medicine. Repeated depositions of corpses over a prolonged period at a single location might signify the recognition of a place for the dead, particularly if that location is difficult to access and other causes for the accumulation of the remains can be ruled out. The fossil assemblages at Sima de los Huesos in Spain and Rising Star Cave in South Africa can be interpreted as early examples of placement of the dead in a designated space (see figure above).

The presence of symbolic aspects elevates treatment of the dead from mortuary behaviour to funerary behavior. The burial reported by the authors reveal the care and effort taken to achieve a desired body position by supporting the child’s head and wrapping the upper body. This burial, together with a previous report of the burial of a child around 74,000 years ago, associated with a shell ornament in South Africa at Border Cave, suggests that a tradition of symbolically significant burials, at least for the very young, might have been culturally embedded in parts of Africa in the later part of the MSA.

Understanding the treatment of the dead intersects with our understanding of social organization, symbolic behaviors and the use of landscape, resources and technology. The act of burial restricts dispersal of the body and the other contents of the grave, increasing the likelihood of archaeological recovery, and provides an unambiguous association between the deceased — and hence the species they represent — and a certain set of behaviours at a specific time and place. Future discoveries in Africa and beyond could shed even more light on the evolution of modern traits and behaviour during the emergence of our species.

* * * * * * * * * * *

¹ The authors are:

* María Martinón-Torres

– CENIEH (National Research Center on Human Evolution), Burgos, Spain

– Anthropology Department, University College London, London, UK

* Francesco d’Errico

– UMR 5199 CNRS De la Préhistoire à l’Actuel: Culture, Environnement, et Anthropologie (PACEA), Université Bordeaux, Talence, France

– SFF Centre for Early Sapiens Behaviour (SapienCE), University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

* Michael D. Petraglia

– Department of Archaeology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany

– School of Social Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

– Human Origins Program, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA

– Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution (ARCHE), Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia

Thank you for an informative and thoughtful article. The discovery of these human remains, some possibly with related artifacts, add to the theoretical possibility of human thoughtfulness, perhaps also indicating fear or dread of death and of the unknown future of dead persons; whether a belief in an “afterlife” is part of these older rituals of course will be difficult to ascertain.

As a side note, I have wondered if the lack of evidence for ritualized burials in our far past could be linked, if even in a very small way, to a practice that is carried on today – the burning of the body and scattering of ashes “to the winds”, so to speak. I could envision that happening, even absent any religious aspect…perhaps as a combination of understanding the need to remove a dead body due to decaying, possibly matched with a desire to both protect the body from predators and perhaps as a recognition or symbolism of some sort.

As someone totally unconnected to any sort of organized religion or beliefs, I still recognize what seems to be a universal and historical need by humans to hold some sort of beliefs – not the “organized” or manufactured religions we see today but a deeply held drive to preserve humanity; whether through fear of the unknown or unexplainable, or some other reason, it exists…how far back it will be recognizable is undetermined, but I am certain the proof of such practices will continue to be pushed back in our distant past.