9 May 2021 – Nowadays, when family and friends bring up the prospect of parenthood, there is this paramount question always on the table: should we? Contemplating the catastrophe of climate change, New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez asked, on behalf of a generation, “Is it still okay to have children?” Her question caught the spirit of the age, spawning countless replies, some incensed, others more empathic. Is it fair to bring a child into a world of mass extinction, looming floods, droughts, shortages of food and water, civil war, resurgent fascism—and now a global pandemic? There’s an old Jewish joke: “In these days, it is better never to be born. Yet who is so lucky? Not one in a thousand!”

* * *

Jackson Kennerly, a philosopher by profession who teaches at Cambridge University, says we should not have been surprised by AOC’s question. It has been studied in sophisticated ways by contemporary thinkers. The first thing they teach is that our retrospective joy, our affirmation of life, is no guide to the wisdom of past decisions. Our hackneyed argument in favor of procreating – that you’ll be glad you did – is decisively flawed. He says:

An example shows why being glad is not enough: Imagine that, while trying to conceive, you are offered a drug that ensures that only sperm with genetic damage are able to fuse with the egg. It is obviously wrong to take the drug. If you do, and if a child is born—prone, perhaps, to recurrent migraines, or suffering from celiac disease—and grows up glad to be alive, as you are glad to be a parent, that doesn’t justify your choice. In a sense, you can’t regret the choice in retrospect, since the existence of the child you love depends on it. If you hadn’t made that choice, a different child would have been born. But your action was immoral. It doesn’t follow from your present affirmation of your child’s existence that you were right to have the child back then.

He says once we separate the parent’s retrospective question – How do I feel about my child’s existence? – from the would-be parent’s quandary, we can ask more clearly whether you should, or may, conceive a child. Philosophers have their doubts. This is true even before we get to the peculiarly awful prospects of the world ahead of us. We need only attend to the inevitable trials of life. I am thinking here of an extraordinary essay by the philosopher Seana Shiffrin, which begins with a niche question in jurisprudence and ends by locating a flaw in the human condition. Reflecting on “wrongful life” suits – in which representatives of a child born with predictable, crippling disabilities sue the parents or their doctors – Shiffrin dwells on the fact that life is invariably hard. Suppose we grant, for the sake of argument, and in favor of procreation, that the gift of life is a benefit, that it’s good for you that you exist. Still, we can’t ignore the downsides. As Shiffrin puts it, matter-of-factly:

By being caused to exist as persons, children are forced to assume moral agency, to face various demanding and sometimes wrenching moral questions, and to discharge taxing moral duties. They must endure the fairly substantial amount of pain, suffering, difficulty, significant disappointment, distress, and significant loss that occur within the typical life. They must face and undergo the fear and harm of death. Finally, they must bear the results of imposed risks that their lives may go terribly wrong in a variety of ways.

When you bring children into being, you give them the gift of life, but you also impose on them these terrible costs. Even if the good outweighs the bad, that may not be enough to justify your action.

In a mordant thought-experiment, Shiffrin compares the prospective parent to a man who drops million-dollar gold bars from a helicopter onto unsuspecting victims, cracking skulls and breaking limbs. On balance, the recipients of this largesse may well be glad they were hit: They’ll recover from the injuries, use the gold to pay their bills, and have a wad of cash left over. But what their beneficiary did was wrong. It is quite different when you harm someone in order to prevent a greater harm- for instance, breaking their leg as you pull them from the wreckage of a burning building. What is not okay is to injure someone in order to deliver what Shiffrin calls “pure benefit” – a nice thing they didn’t need and wouldn’t miss – without their actual consent.

You see where the analogy is going. How are parents different from the crazed philanthropist, conferring benefits their children would not miss – because the children would not otherwise exist – along with, quite literally, the suffering of a lifetime. The unconceived are in no position to accept the bargain, however sensible that might be. Shiffrin’s essay closes with uncertainty. It may not be wrong to have kids, she concedes, but there is a moral objection to be met.

* * *

In the beginning it’s all preventative: No, you can’t just eat more cookies. Broccoli first! You can play with my phone for two minutes, but I need it back. You have to get another shot; it will be over in a second. A lot of this counts as causing harm so as to mitigate further harm. Vaccinations hurt, but they prevent you from getting sick. You could make a similar case for eating vegetables.

But it’s increasingly clear that the bulk of what parents do … the costs you impose … are not preventative. They are intended to make the child’s life better in ways that we hope they will one day appreciate, even if they cannot do so now. How else to justify the nagging insistence “practice the piano every day” – if not to confer the pure benefit of knowing how to play, something she/he doesn’t need and likely wouldn’t miss? Why else require that she/he pick an after school activity? Aspiring parents put their kids through all sorts of travails – going to temple, learning to ride a bike – that are not geared to preventing greater harms but to enhancing future lives.

This all could be a grave mistake, a gold brick dropped from a dangerous height. I do think there are moral risks in such paternalism; when and why parents are entitled to impose burdens on their children to make their lives go better overall is a difficult moral question. But I don’t think the answer is only when imposing such burdens prevents a greater harm. At least for now, you feel justified in making Jamie practice the piano and go to choir.

Within limits, parents are entitled to impose costs on their children for the sake of pure benefit. If your child’s life is good, on balance, that is the bargain you make when you procreate: Shiffrin’s objection can be met.

As we turn from ordinary hardship to the present crises – climate change, fascism, coronavirus – the basic moral calculus does not change. If things get so bad you can’t expect your child to have a life worth living, that is a reason not to procreate. But as long as things are not so bleak, you can justify yourself to your potential child: “You’ll thank me one day—probably”.

Still, this speaks to only part of our dilemma. What AOC was getting at wasn’t just – was not primarily – the hardship your kids will face themselves, but the effects of their lives on others. Each biological offspring adds a half again to your ecological footprint, corresponding to your share in their creation. Don’t complain that it’s their footprint, not yours. The environment cares how much we use and how much waste we produce, not whose column it gets counted in. What should you think of someone who, for his own private reasons, opts for a lifestyle that expands by 50 percent or more the ecological harm he does? Selfish, uncaring, reckless at best.

* * *

A recently influential take is that we cannot rationally decide to have a child because parenthood is an “epistemically transformative experience”. Yeah, I gagged on that one, too. But the point is easy: you can’t know what it’s like to be a parent until you become one, so there’s no rational path to that decision. You don’t know what you’re choosing. (By the same token, I suppose, you can’t know what it’s like to be old and childless until you are. So there’s no rational path to that conclusion, either).

Even those who don’t frame the decision to procreate as a choice of subjective sensations often suggest that the reasons for having kids are basically selfish. We do it because we think, or hope, that it will make our own lives better. Or as Benedick avows in Much Ado about Nothing, “The world must be peopled.” It’s good for humankind to persist, for future generations to build on what we have done and to repair the many things we have done wrong. We need them to take care of us as we grow old, and to a degree we rarely appreciate, our investment in our own activities depends on their place in traditions that project into the future.

* * *

There are no simple answers here. In the end, the practical, nuts-and-bolts question, whether or not to try for a child, leads inexorably to the most difficult problems of moral philosophy, problems about the basis of ethics, as such. Let’s agree that if bias, oppression, and selfishness come naturally to us, they are not thereby justified. What’s natural is not always good. Moved by this fixed point, we may look to Plato, for whom ethics is transcendent, its standards written in the pristine language of Forms, untarnished by the ugliness of human nature.

Nah. I’m sick of Plato. There is no transcendent Platonic reality. But I do believe philosophy matters, especially in its more abstruse and esoteric forms. The problems of metaphysics and epistemology are technical, and intricate, and inaccessible. But it turns out that you can’t respond to a question that stokes fierce emotions in many of us – Is it okay to have kids? – without taking an implicit view of these problems. But as Jackson tells me:

We are not wrong to find the question difficult. We are wrong if we think it’s difficult only because we don’t know how our children’s lives will go, or how they will affect the wider world. It’s difficult because the answer turns on a puzzle that goes back to the birth of Western philosophy. How does our nature as human beings, our peculiar embodiment, shape how we should and should not live?

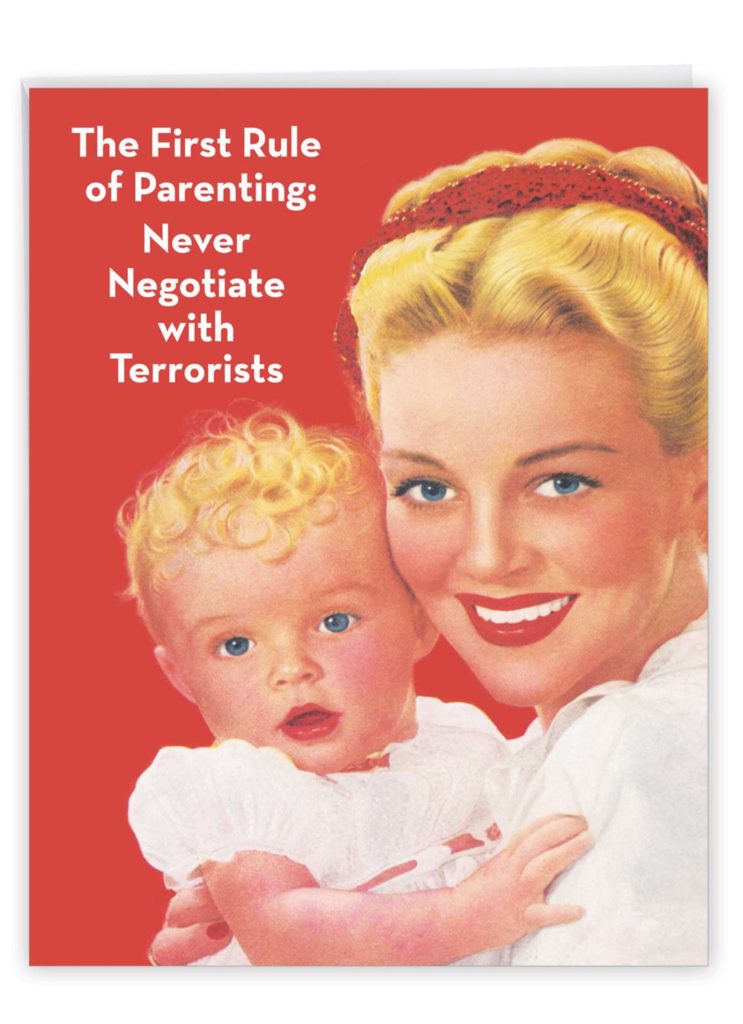

And Moms? Moms are like velcro. They hold everything together, and I have no dang clue how they do it. Ok, not all of them. Some are loud, prickly, and leave an unpleasant sticky residue when they leave. But the good ones? It’s that brilliant combination of one side bristly and the other side soft. That’s how Velcro works and pretty much how moms do, too.

Happy Mother’s Day.