It was never about the money. Well, for Facebook it wasn’t. But as for the Australian media companies …

24 February 2021 (Chania, Crete) – So, it’s official. Google paid up. Facebook stood up and flexed its biceps. The Australian government swatted at the flies in Canberra, gurgled a Fosters, and rolled over. Facebook will walk back its block on Australian users sharing news on its site after the government agreed to make amendments to the proposed media bargaining laws that would force major tech giants to pay news outlets for their content.

The after party will rationalize what happened. But from here in rural Crete (as I write this the largest din is from the goats’ neck bells as they are herded home from the fields), it certainly seems as if Facebook is now able to operate as a nation state. Facebook can impose its will upon a government. Facebook can do what it darn well pleases, thank you very much. The best quote I read, attributed to Josh Frydenberg, the Australian government treasurer:

“Facebook is now going to engage good faith negotiations with the commercial players.”

Are there historical parallels? Sure, how about Caesar and that river thing? Turning points and benchmarks. Ah, what a market play.

If you haven’t been following the development of Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code, a quick recap (summary courtesy of Casey Newton) :

About three years ago, under pressure from Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. (the Australian government and Australian media sold their souls to Rupert) the Australian government set out to devise a way for news publishers to bargain collectively against the technology platforms that had disrupted their advertising businesses. The resulting code, which is expected to become law later this week, achieved that aim.

But it also came with several provisions that the platforms despised. It required them to give publishers advance notice any time they changed ranking algorithms that might affect publishers’ businesses – a privilege afforded to no other industry. It required them to commit to binding arbitration if they could not come to an agreement with any publisher that asked for a deal, leaving the amount of their payments up to an Australian arbiter.

Worst of all, from the perspective of platforms but also of advocates for an open internet, was what made the platforms eligible to be designated under the code in the first place. If a user posted a link to Facebook, or Google included a link in its search engine, they would be liable for the algorithmic disclosures, the publisher payments, the binding arbitration, and all the rest.

Alongside this deeply unpalatable set of requirements, though, the Australian Parliament dangled an alternative in front of the platforms. Sign enough voluntary deals with publishers, they suggested, and we’ll exempt you from all the rest. No algorithmic disclosures, no binding arbitration, no effective taxation on the posting of links.

To be clear, they never presented this as a formal alternative to designation under the code. It wasn’t written into the bargaining code. Parliament just kind of … let it be known that this was an option.

Because Australia’s media market is highly concentrated — there are only three major media companies there — platforms found this option highly preferable to the alternative. (Which, just to underscore this, was to be forced into binding arbitration with every publisher in Australia.) It’s why Google, after threatening to leave the country entirely, ultimately stayed: by buying off News Corp., Seven West, and Nine Entertainment, it believed that it could manage to avoid having to buy off every other news outlet in the country.

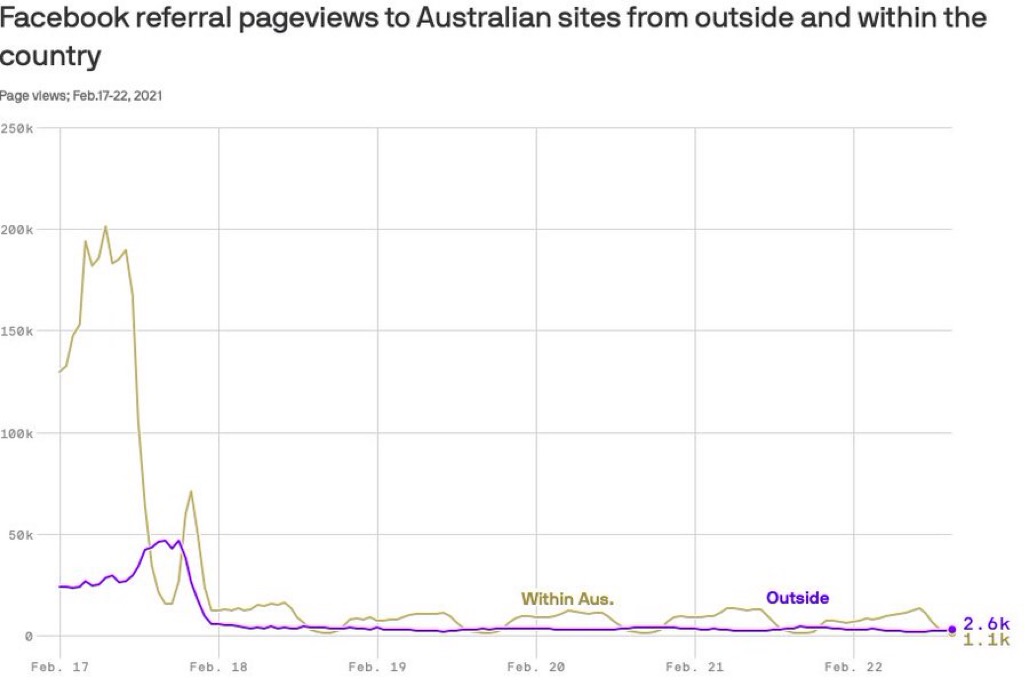

Facebook, though, was less willing to gamble on Parliament’s vague assurances, leading it to block the sharing of links last week. And after traffic to Aussie publishers predictable fell off a cliff over the past week:

The government came back to the negotiating table ready to cut a deal. On Monday, a bargain was struck.

The deal

Joshua Benton, who founded Nieman Lab in 2008 and served as its director until 2020, and is now the Lab’s senior writer, has been the “must read” chap the last 10 years or so on just about everything related to Facebook. A link to his recent piece on the Facebook/Australia imbroglio in a moment.

NOTE: if you are a journalist, Nieman Lab is on your daily read list. It was among the first to recognise the onslaught on the news and information business by the Big Tech platforms. Joshua created the Nieman Journalism Lab (its full name) in cooperation with the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University in an effort to investigate future models that could support quality journalism. They pioneered narrative journalism, with the jewel being their annual conference (the largest of its kind) which attracts hundreds of writers, filmmakers, and broadcasters to Boston, Massachusetts.

It took less than a week for Australia to backtrack. The mandatory arbitration that was the key to Australia’s proposed new law has been tossed out the window. Well, as Benton writes “it has been reduced to a matter of theory. Facebook can now decide to offer different publishers whatever amount it wants, including nothing at all, without risk of penalty.”

Facebook can do whatever it likes, negotiate with whatever Australia media company it likes – as Campbell Brown’s statement (she is the head of global news partnerships at Facebook) makes clear (emphasis in italics are mine) :

After further discussions with the Australian government, we have come to an agreement that will allow us to support the publishers we choose to, including small and local publishers. We’re restoring news on Facebook in Australia in the coming days. Going forward, the government has clarified we will retain the ability to decide if news appears on Facebook so that we won’t automatically be subject to a forced negotiation. It’s always been our intention to support journalism in Australia and around the world, and we’ll continue to invest in news globally and resist efforts by media conglomerates to advance regulatory frameworks that do not take account of the true value exchange between publishers and platforms like Facebook.

For the platforms, the money is not and has never been the issue here. Facebook and Google are both perfectly willing to throw money at publishers to hold off regulation. That has been well documented despite the (“we-really-are-not-that-ignorant-we-just-like-to-sensationalize-stuff-and-boy-do-we-miss-Trump”) main stream media.

Yesterday, Benton wrote a brilliant piece entitled “Facebook got everything it wanted out of Australia by being willing to do what the other guy wouldn’t” and well worth your time if you are into this stuff. I’ll summarise his key points and then provide my own comments.

• From the duopoly’s perspective (Facebook and Google), the biggest problem with paying for all the news coursing through their digital veins isn’t the money. They have plenty of money. It’s that paying for news in any systemic way would attack their core advantage as platforms: organizing other people’s content.

• No, any sort of systematic, performance-driven payments to publishers based on the value they offer platforms are a no-go. So Facebook and Google have normally always responded by looking for other ways to deal with the PR headache by getting money to news companies.

• If there were suddenly a law that says Google has to pay for some kinds of information in its search index — or that Facebook has to pay to have some kinds of information in News Feed — that core element of their model would be at risk. Suddenly, instead of being a toll road that commuters pay to use, you have to pay drivers for the privilege of using you? That’s the unthinkable.

• Facebook is a corporate nightmare that has done very real and meaningful damage to democracy. Australian regulators carry water for Rupert Murdoch and have been proposing a policy that would, as Tim Berners-Lee says, make the web “unworkable.” But a bad company facing bad regulations distills down to pure power, and by shooting the hostages, Facebook made it very clear where that still lies [read the full piece. The Keyser Söze analogy is brilliant].

And so, it seems, the deals will be done. (Some of) Australia’s biggest publishers will get their multimillion-dollar paydays … and might even choose to spend some of that money on journalism (there was a question if any of the money Facebook gives to publishers is required to be spent on journalists’ salaries or news gathering. There is no such requirement).

Journalism has great value — including financial value — and a world where Facebook and Google are paying to ensure that there is high-quality news on their platforms is far preferable than the alternative.

But .. it also advances a world where legacy publishers are even more dependent on the biggest companies of the moment, rather than on their own innovations. And whether these deals result in the creation of even a single new job in journalism remains depressingly irrelevant to everyone involved.

More depressing is the fact that we should expect to see similar deals proposed in other countries, and soon. It’s now clear that if you present platforms with the option of being subject to an unworkable “news bargaining code” or avoid it entirely in exchange for a bribe, the platforms will probably take the bribe. Governments can take credit for “reining in big tech,” as Australian politicians have done repeatedly in the past several days, but the only thing that changes is the number of zeroes in various media conglomerates’ bank accounts. For them, it was only about the money.

My other thoughts

The exponential growth of big tech platforms in information delivery has led to the digital disaggregation of the newspaper business, and other old line media. I’ve written about that ad nauseam as have scores of other journalists.

Ah, the internet used to be a vast and wondrous place. It was fun. It began simply as a giant data set, a contextless compendium of information consulted via websearch, a query to fill whatever momentary gnaw had interrupted your day. Once the internet evolved past the novelty of communicating over distance, it found value in experience. Forums proliferated, naturally subdividing so that people congregated around shared interests or life events.

Those of us who were into the Net early on will well remember that waaaaaaay back in 2003 there was the launch of a now legendary community-run MetaFilter which was called “Ask MetaFilter” where users could pose questions to the “hive mind.” AskMeta still exists but it has become what Peter Rubin (culture editor for Wired magazine) calls a “lurker’s dream”. You scroll through not to answer, or even look for something specific, but just to absorb the amazing content: road-trip conversations, playlists, science and literature tutorials – complete lives and stories revealed not in parcels but told in full. It is a delight. What “just scrolling the internet” is all about.

But then, alas, scale and greed and countless other culprits spun the internet geologic clock backward. A realm that once comprised countless nations has become a supercontinent, a monolith of homogenized use and mood. We have “hell sites” (Facebook and Reddit and Twitter and 4chan to name but four), not web sites, that manage to be more existentially unsatisfying everyday, manipulating our traditional knowledge ecosystem. And so our days are filled with discussions of “the struggle to detoxify the internet” and “the oxygen of amplification” which have reconfigured the information and media landscape … and not in a good way.

As recently as 17 years ago, before the internet completed its digital disaggregation of the newspaper business, I was a two-paper-a-day-via-the-plastic-delivery-bag guy: the Financial Times and Le Monde. But over time I would turn first to my desktop computer and then to my laptop and finally to my phone for news; digital subscriptions became my primary “information delivery system”. Beckoned incessantly to click on one link or another. Or still another. Those mysterious algorithms known only to the gremlins of Silicon Valley pushing me toward stories that those gremlins reckon must be of related interest. (Although I have returned to my old morning ritual of actually reading a print paper, the FT).

So I still watch the break-down and disintegration of my “imagined communities” (to use the late Ben Anderson’s term) … nation states, professions, civility, legal systems, etc. But I find the need to ask more questions than I did. It’s Socratic: examine one’s life. There are things that burn away at me, not only as a private individual, but also as a citizen of our century, our pixelated age. What can I do with the absurdity of life that swarms me daily? Well, the most I can do is to write — intelligently, creatively, evocatively — about what it is like living in the world at this time. It’s what led me to create Luminative Media.

We live in a time where new forms of power have emerged, where social and digital media have been leveraged to reconfigure the information landscape. It is a new domain, still evolving, but the Facebook/Australia imbroglio has certainly confirmed the death of the traditional information ecosystem.