Plus, a book you really need to read

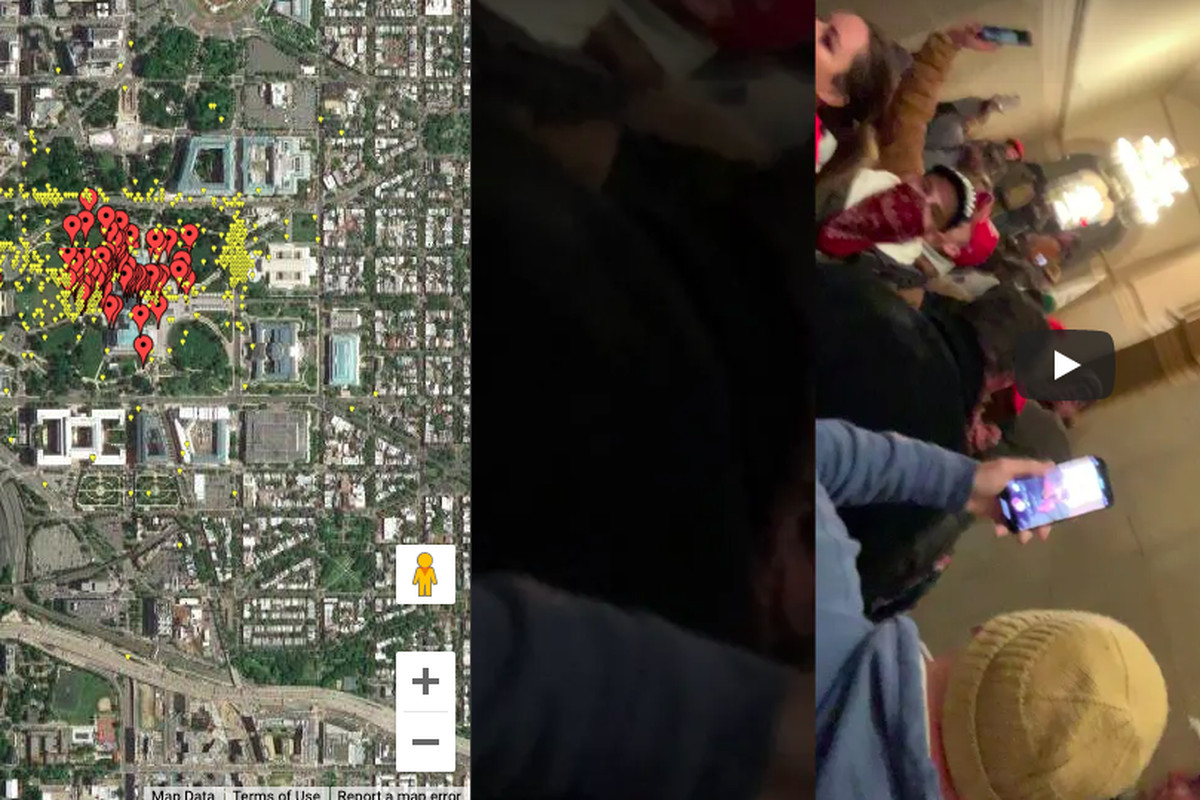

Source: https://thepatr10t.github.io/yall-Qaeda

Source: https://thepatr10t.github.io/yall-Qaeda

16 January 2021 (Chania, Greece) – Ah, the old days. Policeware/intelligence vendors once commanded big $$$ to help you match a person of interest to a location. But over the last decade prices have come down. Some useful products cost a fraction of those industrial strength, incredibly clumsy tools. Commoditization reared its ugly head. The latest surveil innovations lost their luster as they became common and a part of our expected daily life. Prices dropped with the rise in competition among those who provided the service.

But that’s commoditization for you. Since the dawn of the digital age, technology has continued to move forward, as innovations such as laptops and mobile phones and software and coding and services grew cheaper and more readily available – turning into a commodity. There are some absolutely stunning products out there in “policeware” which will lead this race but let’s leave them out for now.

The focus of this post is the useful information derived from the deplatformed Parler social media outfit. An enterprising individual named Patri10tic performed the sort of trick which Geofeedia made semi-famous. You can check the map placing specific Parler uses in particular locations at the U.S. Capitol based on their messages by spending some time on this link.

Just to highlight a few points certainly known to any of us that have worked in intelligence or the legaltech industry:

1. Metadata can be more useful than the content of a particular message or voice call

2. Metadata can be mapped through time creating a nifty path of an individual’s movements

3. Metadata can be cross-correlated easily with other data. If you follow the myriad of experts on Linkedin who know this stuff cold, or read the works of Gordon Corera, John Hughes-Wilson or Bruce Schneier (plus a host of others but they are my favs; email me and I’ll send you a reading list) the ease and magic of cross-correlation is an eye opener.

4. Metadata can be analyzed in more than two dimensions.

As a journalist, this type of data detritus has enormous value (see book review below). That is the reason third parties attempt to bundle data together and provide authorized users with access to them.

And industrial strength “policeware”? Almost anyone can replicate those systems that cost as much as seven figures a year or more – from their laptop at a coffee shop. The Parler analysis demonstrates that there are many uses for low or zero cost geo manipulations.

Which takes me to an extraordinary book.

Eliot Higgins’s book is not out yet, set to release in a few weeks. But as my regular readers know I am in a publisher consortium and so I receive lots of books weeks before their publication (normally cheaply produced paperback copies) in order to review them and/or to quote them in my blog posts to promote them.

I have quoted Bellingcat in numerous posts but for those who need some background, Bellingcat is the open-source investigative agency founded by Eliot Higgins, a British researcher and citizen journalist.

Bellingcat’s name comes from the old fable in which the mice hung a bell around the cat’s neck so that it would never catch them again.

In a video posted on YouTube last month, the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny described in chilling detail how a secret service hit squad had poisoned him with the novichok nerve agent. Navalny identified the intelligence operatives involved. He even telephoned one of them later and tricked him into describing how he smeared novichok on Navalny’s underpants, the subject of another video. The Kremlin dismissed the accusations on the novel grounds that it would have done a better job of killing Navalny had it wanted to do so. But Navalny’s video has severely dented the Kremlin’s denials of involvement and presented an alternative story to 22m viewers, something unimaginable in the pre-internet era.

This extraordinary exposé was aided by Bellingcat. Using airline passenger manifests, telephone records, geolocation data and personnel files, all circulating on the darker recesses of the Russian internet, Bellingcat was able to piece together the plot to poison Navalny.

That story, plus scores of others detailed in the book, speak to Bellingcat’s roll: to take aim at those who only bewail the downsides of the internet. As Higgens says in his book:

“At Bellingcat, we do not accept this cyber-miserabilism. The marvels of the internet can still have an impact for the better.”

Higgens also details how his team of researchers helped unmask the Russian spies responsible for the novichok poisonings of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury in 2018. Plus how they tracked down the Russian Buk anti-aircraft missile system that shot down Malaysia Airlines MH17 over eastern Ukraine in 2104, killing 298 passengers and crew. And how they documented chemical weapons attacks in Syria and human rights abuses in Libya, all of which has been used by the International Criminal Court.

Simply put, in his view, the internet remains an astonishing resource for helping redress the power imbalances between the rulers and the ruled. History is no longer just written by the winners, but filmed by the losers on their smartphones. To me, Bellingcat stands at the nexus of journalism, activism, computer science, criminal investigation and academic research.

This is not meant to be review of the book so just a few salient points that relate to my comments above about metadata and the many uses for low or zero cost geo manipulations:

1. In the book, Higgins recounts how he dropped out of college in the 1990s and worked in a series of dead-end jobs in Leicester, UK, taking refuge in video games. But his fascination with the Arab Spring sparked a new obsession with current affairs. By scouring online videos, using translation services and Google Maps, Higgins was able to piece together the unfolding drama and contributed to news blogs before setting one up himself. He built up a network of fellow citizen journalists around the world (more on that below), each having an area of particular expertise.

2. The investigators turn all their collected archive information into usable datasets, which can be used to identify patterns of behavior, visualize entire landscapes and show how things have changed over time, and cross correlate.

3. Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) has enabled many forensic breakthroughs in recent years and Bellingcat has made full use of it. Its origins lie in the world of intelligence and law enforcement. It was the 9/11 Commission that in 2004 first recommended the creation of an open-source intelligence unit, a proposal reinforced a year later by the Iraq Intelligence Commission. But the methodology has found its most innovative and effective use in the hands of journalists.

4. The central pursuit in open-source investigations is finding publicly accessible data on an incident, verifying the authenticity of the data, using that data to confirm the temporal and spatial dimensions of the incident, and cross-referencing the data with other digital records.

5. An open-source investigator will thus start by scouring social media for postings from the area around the time. For instance, once such images are found, they will be geolocated using Google Earth to cross-referencing geographical features. The time for each image will then be confirmed, using digital sundials to calculate shadow length and direction. For instance, a route for a missile launcher can then be constructed by placing the photographs on a map along with the time for each sighting.

6. For all its utility, such material always carries the risk of inauthenticity or manipulation. As Higgens points out, with the help of its ally Russia, Syria adapted to this new media environment by mobilizing armies of trolls to add digital noise to the mix, further diminishing trust in such material. This is where open-source verification becomes essential, establishing the authenticity of audio-visual material before any conclusions can be drawn from them.

7. And an important note. The remoteness of open-source analysts from the subject of their analysis is not as absolute as its critics make it out to be. Much of the data used in open-source analysis comes from witnesses on the ground who have more immediate access to events.

8. Most open-source investigators aren’t formally employed as journalists – many emerged from a gaming subculture where street cred derives from the economy and precision of one’s method – and professionals from other fields of expertise such as architecture, medicine, chemistry, finance, and law have found uses for their specialist knowledge in unraveling forensic puzzles. The British-Israeli architect Eyal Weizman has pioneered the entirely new field of forensic architecture, using open-source data for spatial investigations into human rights violations; the chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta has contributed to several Bellingcat investigations; UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Investigations Lab recruits from over a dozen disciplines.

9. For me, this is the closest that journalism has come to a scientific method: the transparency allows the process to be replicated, the underlying data to be examined, and the conclusions to be tested by others. This is worlds apart from the journalism of assertion that demands trust in expert authority.

BOTTOM LINE: In the years to come, responsible publishers will have to invest in greater capacity for robust fact-checking and digital verification. I think only media giants like the Times or the BBC have the resources to maintain fully-staffed open-source investigations units. But I am heartened that organizations like Bellingcat are receiving more and more funding.