The year seemed to bring home that we live in an inherently unstable system: everyone is connected but no one is in control.

31 December 2020 (Chania, Crete) – My good friend Shaun Usher runs a blog called Letters of Note. He troves biographies, autobiographies, libraries, correspondence files, etc. to find letters written by such folks as Zelda Fitzgerald, Iggy Pop, Fidel Castro, Leonardo da Vinci, Bill Hicks, Anaïs Nin, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Amelia Earhart, Charles Darwin, Roald Dahl, Albert Einstein, Elvis Presley, Dorothy Parker, John F. Kennedy, Groucho Marx, Charles Dickens, Katharine Hepburn, Kurt Vonnegut, Mick Jagger, Steve Martin, John Steinbeck, Emily Dickinson …. oh, the list of authors is endless. He also has hundreds of letters sent to him by subscribers and fans.

It was through Shaun I was able to troll bookstores and collectors and assemble my own trove of letters from some of my favorite authors such as Michel Montaigne, Henry Miller, Henry James, and H. L. Mencken.

Note: Michel Montaigne was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance, known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. He showed how to merge casual anecdotes and autobiography with intellectual insight. His work gave birth to many literary devices, such as the British magazine tradition of a weekly diary – on the issue, but a little distant from it, personal as well as political, conversational more than formal. I have tried to emulate that in my writing.

Shaun had not posted a lot in recent years but when he did they were zingers: the first recorded use of the expression “OMG” was in a letter to Winston Churchill; Gandhi’s appeal for calm to Hitler; Leonardo da Vinci’s remarkable job application letter, etc. These were celebrations of the power of the written word.

In 2019 and 2020 he ramped up with a Substack newsletter – the online platform that provides publishing, payment, analytics, and design infrastructure to support subscription newsletters. Shaun is an example of one of the biggest ongoing changes in media … accelerated by the coronavirus lockdown … which I wrote about in my “TL;DR” post last week: the Cambrian Explosion of virtual spaces. Over the last 5-8 years we have been learning so much about the dynamics of digital places and semi-spatial software, and the mega-leap in video and film production. This is driving an incredible evolution in design and content patterns which will accelerate over the coming months and years.

In his end-of-the-year newsletter, Shaun spent a fair amount of time looking for mention of the New Year in the letters of others. Ones on the negative side. On the downbeat. For me, this was the standout:

So we go into this happy new year, knowing that our species has learned nothing, can, as a race, learn nothing — that the experience of ten thousand years has made no impression on the instincts of the million years that proceeded. Maybe you can find some vague theology that will give you hope. Not that I have lost any hope. All the goodness and the heroisms will rise up again, then be cut down again and rise up. It isn’t that the evil thing wins — it never will — but that it doesn’t die. I don’t know why we should expect it to.

It seems fairly obvious that two sides of a mirror are required before one has a mirror, that two forces are necessary in man before he is man. I asked Paul de Kruif once if he would like to cure all disease and he said yes. Then I suggested that the man he loved and wanted to cure was a product of all his filth and disease and meanness, his hunger and cruelty. Cure those and you would have not man but an entirely new species you wouldn’t recognize and probably wouldn’t like.

John Steinbeck in a letter to Pascal Covici dated 1 Jan 1941, from “Steinbeck: A Life in Letters”

The COVID-19 pandemic was a challenge perfectly crafted to feed on our every societal and informational weakness. From the American perspective it was worse: health insurance, inequality, federalism, leadership, Trump, individualism, social media, broadcast media – all the shortcomings of every one of those elements felt built to exacerbate this crisis.

COVID was an enemy which had no side. Whatever/whoever your enemy or your country’s enemy has been, there was always a very clear character that brought you grief. That’s how our reality show works. It’s maddening, but we’ve all learned to process everything like this. This coronavirus was clearly none of the above. There was no “us” versus “them”.

We experienced many things in 2020, and for many of us they were deeply painful. But many (finally) crossed a critical threshold that most of us (at least those in the West) have known for a long time – that the world was “techonomic”. Tech has decisively become fully intertwined with the functions and institutions of society, politics and economics. Digital platforms have integrated themselves into every fabric of our social, economic and political lives. This year even the most obtuse could not fail to witness technology’s power all around us, for both good and ill. Tech’s pre-eminence as a force, an agency, a vehicle, and an instrument was everywhere evident. But we also have to be mindful of that built-in pernicious fallacy. Which is that to believe that change is driven by technology, when technology is driven by humans, will render force and power invisible.

If we did not live in a society that was digitally interconnected, for obvious example, the pains of the year would have been far more unbearable. For those still omitted from that connected society – like the roughly 30% of American schoolchildren who can’t connect – it was unbearable. Among many essential techno-epiphanies of 2020 is to acknowledge that excluding anyone from a broadband internet connection is like marooning them on a desert isle. Access is now a human right.

Those of us privileged to have such connections used them this year as an isthmus to connect our quarantined homes to the larger world – to work, to shop, to stay connected to friends in myriad ways, to engage in politics, and to do so many little things that make life good. As has often been remarked, if this pandemic had happened even five years ago it would have been much more economically and socially devastating. Tech’s many recent advances and innovations made all the difference.

But the dark side is equally evident. The year is ending with a cyberattack so vast as to be unquantifiable, an intrusion that appears to still be lurking in the bowels of a shocking percentage of our most important governmental and commercial institutions. The ramifications are likely to be felt for years, in ways we cannot predict, but that certainly will be malign. It will be fodder for my first post in 2021.

It all seemed to bring home that we live in an inherently unstable system: everyone is connected but no one is in control. The world is always in overdrive, with a relentless acceleration in human development over the past two centuries. We are living longer, producing more, consuming more, devouring energy and space on an unprecedented scale – and generating waste and emissions in tandem. To paraphrase Mary Bateson, the great irony of our time is that even as we are living longer, we are thinking shorter. This pandemic was “nature’s revenge” on our voracious species.

Our species will (probably) prevail in the current crisis. But that is hinged on the world successfully executing the most complicated vaccination program in history – and in the U.S., persuading a frayed and fractured nation to continue using masks and avoiding indoor crowds, and countering the growing quagmire of misinformation – as well as successfully monitoring and countering changes in the virus itself. The pandemic will end not with a declaration, but with a long, protracted exhalation.

We all learned much. In retrospect, many Western health experts were too focused on capacities, such as equipment and resources, and not enough on capabilities, which is how you apply those capacities in times of crisis. As scores of epidemiologists pointed out, many rich nations had little experience in deploying their enormous capacities, because most of them never had outbreaks. By contrast, East Asian and sub-Saharan countries that regularly stare down epidemics had both an understanding that they weren’t untouchable and a cultural muscle memory of what to do.

More importantly, we were all reminded that the glue holding modern societies together is alarmingly fragile, with devastating consequences that we are only just beginning to understand. I opened my “TL;DR” piece (referenced above) with a quote from the evolutionary biologist E.O. Wilson from one of my favorite books which he published in 2012, The Social Conquest of Earth:

“We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”

As he details in that book, kin psychology lies at the foundation of all groups. Humans form factions around almost anything and simply being a member of a group is usually enough. What we’re witnessing today reveals a logic of disintegration, in which national, ethnic and religious differences are being “tribalized” on a planetary scale.

All of this reminded me of my comfort in living and writing from a remote part of Greece, a bit mysterious at times and even a bit impenetrable at times, but awesome: made of earth, air, fire and water. It breathes. Here you can get a bit nearer to the stars and the ether.

What will we remember? The influenza pandemic that began in 1918 killed as many as 100 million people over two years. It was one of the deadliest disasters in history, and the one all subsequent pandemics are now compared with. It really disappeared from the public consciousness. It was swamped by World War I and then the Great Depression. All of that got crushed into one era. An immense crisis can be lost amid the rush of history, and I wonder if the fracturing of democratic norms or the economic woes that COVID-19 set off might not subsume the current pandemic. As Martha Lincoln noted in one of her blog posts (she is a medical anthropologist at San Francisco State University and has been a “go to” source for me):

“I think we’re in this liminal moment of collectively deciding what we’re going to remember and what we’re going to forget.”

In The Past Is a Foreign Country, the historian David Lowenthal wrote, “The art of forgetting is a high and delicate enterprise … It can be a process of social catharsis and healing or one that sanitises and eschews the past.” The choice between those options is now before us, as the coronavirus pandemic enters its second full year. We will decide whether to resist the decay of memory and the elision of history – whether to forget, or to join the many who will never be able to.

Nope. We are not out of the woods but the trees do seem to be thinning out. I will remain (a bit) hopeful.

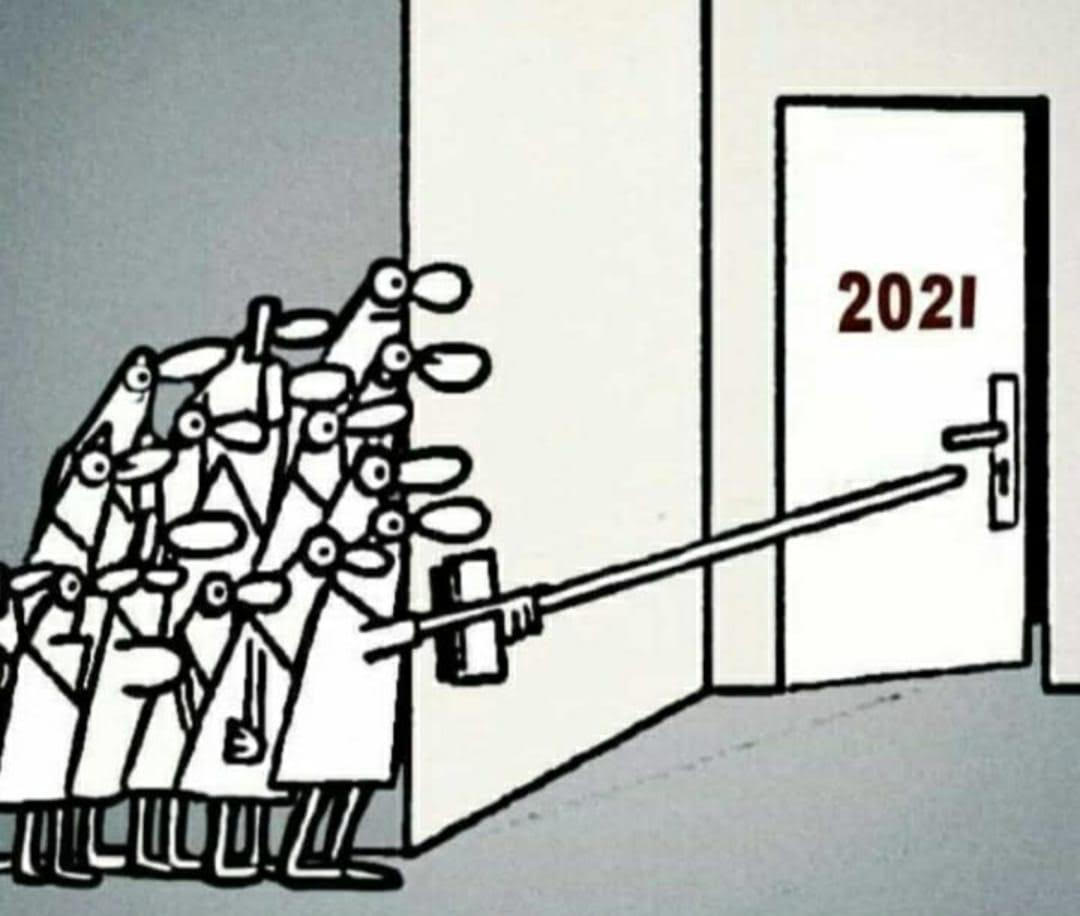

So, as we stagger into 2021, let me try and leave you with some uplifting words from my TikTok guru: