Data has become a crucial part of our infrastructure, enabling commercial and social interactions. Rather than just tell us about the world, data acts in the world. Because data is both representation and infrastructure, sign and system.

And people are completely missing the importance of augmented reality technology: looking at screens and pecking at keyboards will surely seem quaint by 2030

27 November 2020 (Chania, Crete) – Over the last few weeks I have written about Google’s data slurping and that we’ll need to brace ourselves for even more data grabs given Apple’s new M1-based machines which have launched a new type of computer system. We are making a major philosophical leap in the underpinning of computers and mobile devices. And I have written about the recent U.S. elections and what they have taught us about the futility of tech regulation.

It all relates to the insane conversations I have with “experts” who think data privacy is actually possible. Data is in perpetual motion, swirling around us, only sometimes touching down long enough for us to make any sense of them. We use data, these numbers, as signs to navigate the world, relying on them to tell us where traffic is worst and what things cost and what are friends thinking and what our friends are doing and placing an Amazon order and letting Amazon “logistic” the delivery of the package, etc., etc.

And because we do this, data has become a crucial part of our infrastructure, enabling commercial and social interactions. Rather than just tell us about the world, data acts in the world. Because data is both representation and infrastructure, sign and system. As media theorist Wendy Chun puts it, data “puts in place the world it discovers”. Restrict it? Protect it? We live in a massively intermediated, platform-based environment, with endless network effects, commercial layers, and inference data points.

For those of you who followed my series last year on the Appboy and Disconnect data trackers, you know that each of us who use an Apple or Android phone (and even your laptop) will engage with 5,400+ trackers, mostly embedded in apps, most feeding to data brokers. According to the privacy firm Disconnect, you spew out an average of 1.5 gigabytes of data about yourself over the span of a month. But you need special software to track all this. This all feeds into the big General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) problem over “transparency” and why EU citizens are struggling with “Data Privacy and Data Subject Access Requests” (DSARs) mandated under the GDPR: if you don’t know where your data is going, how can you ever hope to keep it private? (DSARs are a sham but data privacy vendors will not tell you that because they need to make money from their services. I’ll have a detailed post on “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” of DSARs in the coming year).

Big Tech has outgrown your office and your living room. They want to be with you literally every where you go, and constantly seduce you with entertaining and immersive experiences. The more of your attention they can monopolize, the more money they can make from selling chunks of it to advertisers and people developing software on their platforms. Four companies … Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft with a combined market capitalization of over six trillion dollars (as of 27 November 2020) … are mortal enemies fighting expensive digital wars of attrition in every setting – except one.

OpenStreetMap, the free Wiki map of the world

Jennings Anderson, Joe Morrison, and Vicky Johnson-Dahl (cartographers and geospatial specialists) along with Hacker News have done heroic work examining OpenStreetMap. I will try and consolidate all their findings and pepper it with my own thoughts.

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is the largest volunteered geographic information project in the world, characterized both by its map as well as the active community of the millions of mappers who produce it. What likely started as a conversation in a British pub between grad students in 2004 has spiraled out of control into an invaluable, strategic, voluntarily-maintained data asset the wealthiest companies in the world can’t afford to replicate – forming an unholy alliance of the world’s largest and wealthiest technology companies. The most valuable companies in the world are treating OSM as critical infrastructure for some of the most-used software ever written.

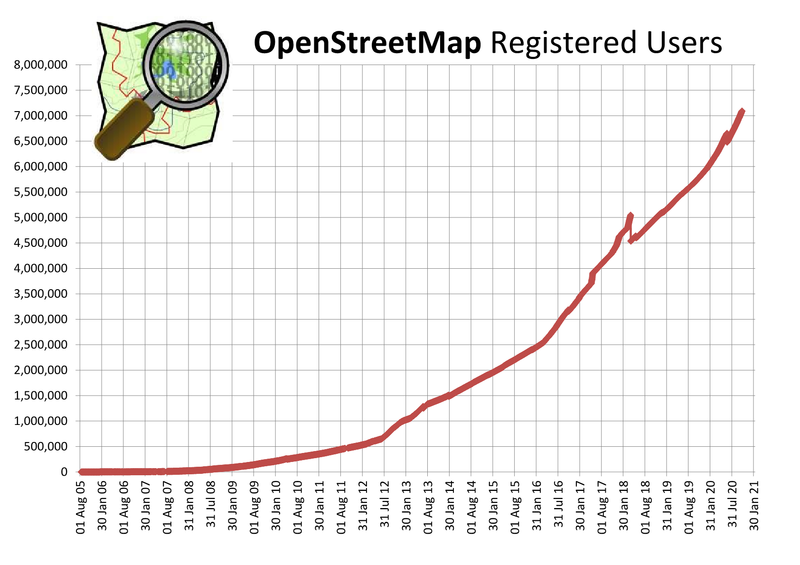

The numbers are incredible. Over 1.5M individuals have contributed data to it. It averages 4.5M changes per day. The stats page on the OSM Wiki is a collection of hockey sticks that look like this:

Cumulative registered users over time. Source: https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Stats

You can think of OSM in several ways:

• A distributed community of mappers contributing information about the geography of the world to a common repository

• A free web map hosted at https://www.openstreetmap.org/

• A loosely affiliated collection of free and open source tools for mapping the world

• A real-time stream of instructions representing how to add, change, or remove cartographically projected geometries and associated metadata based on a prior state

• … a kind of Google Maps, but openly licensed

It’s hard to get people to agree on what exactly OSM is, but almost everyone agrees on one thing: it’s extraordinarily valuable and important. And for those of you who read my posts, there is nothing new here. I have been writing about the advances in geospatial technology that few have been paying attention to.

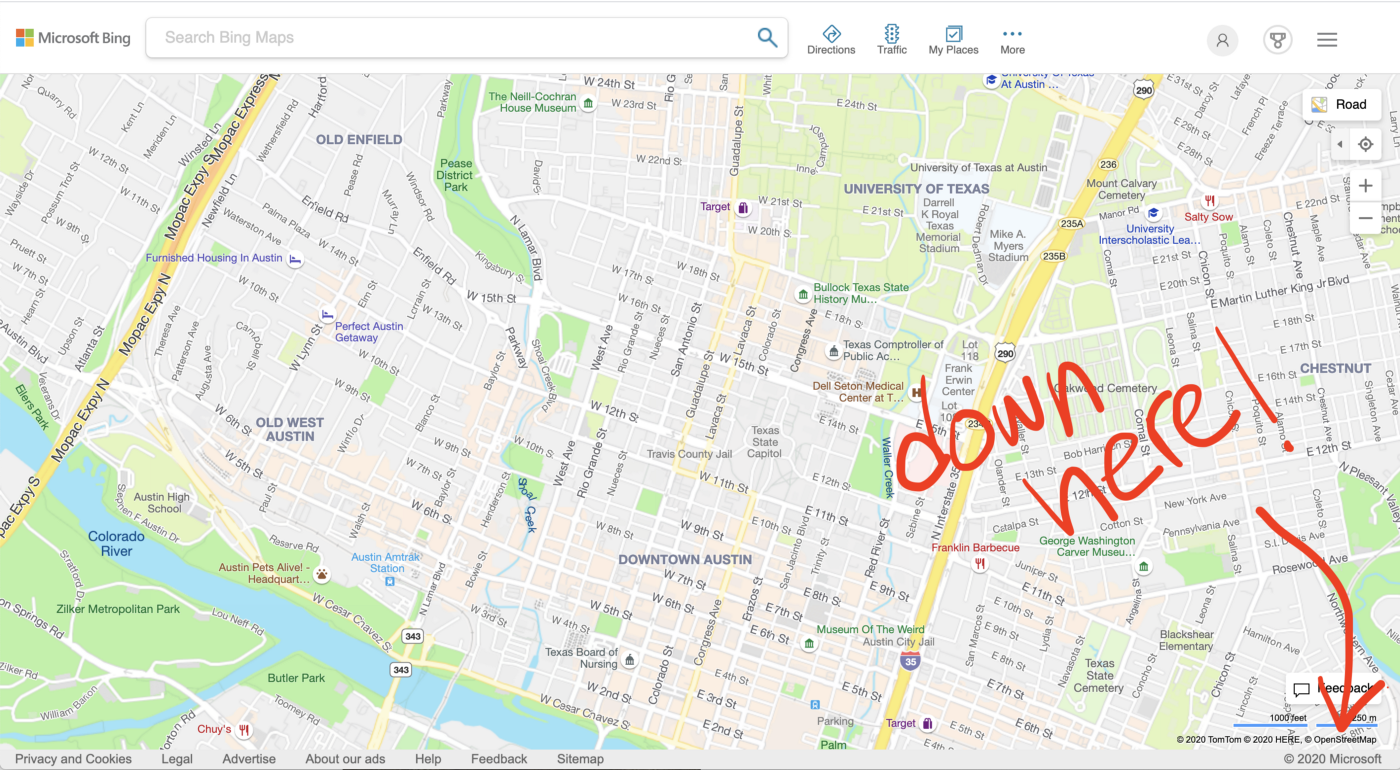

But news alert: if you’ve ever opened Snap Maps or Apple Maps or Bing Maps or even just peeked at the dash of your obnoxious neighbor’s new Tesla … you’ve used OSM.

NOTE: as an astute commenter on Hacker News pointed out, Tesla uses Google Maps for its dashboard. They only use OpenStreetMap for the auto-summon feature, which incidentally has resulted in lots of parking lots being added to OSM by the Teslarati.

And depending on what you are using, you can check the attribution:

So, of course, one of the consequences of increased corporate involvement in OSM is a significant backlash from members within the OSM community that feel the community (and data) is being irreversibly adulterated by these profiteering intruders. None of these companies is essential to OpenStreetMap. They are contributors, but OpenStreetMap could work perfectly well without them. The mainstay of OpenStreetMap is the millions of hobbyists, individuals that contribute to OpenStreetMap.

So what’s motivating the “Big Tech Gang of Four”? Joel Spolsky wrote earlier this year about the concept of “Commoditizing Your Complement” (securing chokepoints, getting a quasi-monopoly), and Joe Morrison has written about why Facebook acquired Mapillary and then gave away all the data they had just purchased, for free. Both are relevant to this conversation.

SHORT NOTE: I’ll get to Mapillary shortly but just a few points.

This year, the big news in the geospatial world was Facebook’s acquisition of Mapillary. For those unfamiliar, Mapillary is a darling of the mapping world and one of the highest-profile geospatial startups of the last decade – launched in 2013, their mission was to create a global street-level imagery dataset to rival Google Street View.

Mapillary was the prototypical “venture-scale” business – preposterously ambitious, technically impressive, inarguably valuable for the world, and plausibly monetizable. What Mapillary accomplished in a short seven years is simply staggering. Google, with an enormous head start and untold resources at the ready to support Street View announced last year that they’ve collected over ten million miles of street imagery. Mapillary, on the other hand, crossed three million miles of mapped streets in 2018 and has more than doubled the number of images in their catalog in the years since (to over one billion!), putting them squarely in the same conversation as Google. That’s an insane accomplishment for any company, let alone a startup who, over its lifetime, raised ~$25M or about half of the annual compensation package for a typical member of Google’s C-Suite.

Why did Facebook buy Mapillary, and then give all that data away, for free? to that? Short answer: to hurt Google, but it also complements their augmented reality business. Long answer? Achieving mapping hegemony which every Big Tech firm needs/wants. For more “long answer”, see the geospatial technology paragraphs which conclude this post.

Whatever the motivations of these mega-corporations with OpenStreetMap, they’ve succeeded in carving out a niche for themselves (in effect following Spolsky’s advice) within the OSM community whether the hobbyists like it or not. I’d like to highlight a nuance often lost in this discussion – just exactly who are these companies hiring to add data to the map? They are often already-active, enthusiastic contributors to OSM. These are people living the open data fanatic’s dream: getting paid to do a job they find so fulfilling they would otherwise do it for free in their spare time.

And, yes, for Facebook, there’s obviously a lot more to it than just sticking it to Google. Facebook, for instance, has ambitions of building new types of digital experiences that interplay with the real world (as evidenced by their focus on augmented reality and acquisition of novel user interface technology like CTRL-labs). Apple has added LiDAR to its new line of iPhones and iPods allowing customers to scan the 3D world in high fidelity among other exciting uses.

As I noted above, these firms have outgrown your office and your living room. Whether you like their motivations or not, the result is a desire to map the world in higher fidelity and at larger scale than even they can afford to accomplish independently. And that has, for better or worse, brought their interests into alignment with the grassroots OSM community.

Well, tough question. Are you a data privacy freak or antitrust freak? Well, I suppose any time the wealthiest institutions in history are quietly collaborating on something, I think it’s worth noting. There does not seem to be a precedent for such a collaboration: mega-corporations working with a global community of volunteers on a public dataset.

But if any of you have worked on enormous database projects … I am one of 3,000 working on a dataset of global data slurps, updated daily, and distributed to a selected client list … you know it requires ceaseless, grueling work to keep updated, and that means serious investment of time and money. One of the key differences between our data slurping projects and OSM is the exponential size of the OSM community of contributors. Without it, the project is “default dead,” as they say in Silicon Valley. Map data goes stale fairly quickly and therefore requires constant life support.

And yet that community is precisely what attracts corporate contributors. OSM provides two advantages over just buying privately collected data:

• Existing data is free and growing apace

• But proprietary data contributed to OSM may also be expanded upon and/or maintained at no additional expense by the community

So, the squirming: the community freaks out at the idea that their contributions to OSM help FAAM … after all, do they really need the help? But what’s beautiful is that FAAM is contributing (rather than passively mooching) because of the compounding value of having any/all data make it into the community’s growing number of hands.

BUT … and almost inexplicably … the goals of the OSM community and corporate contributors seem to be largely aligned. They all want an accurate, ubiquitous map of the world that can be maintained in perpetuity as sustainably as possible. It’s the opposite of the Tragedy of the Commons – all of the private property holders, acting in their own self interest, are enriching the common resource rather than depleting it. But we have yet to see how this will actually morph.

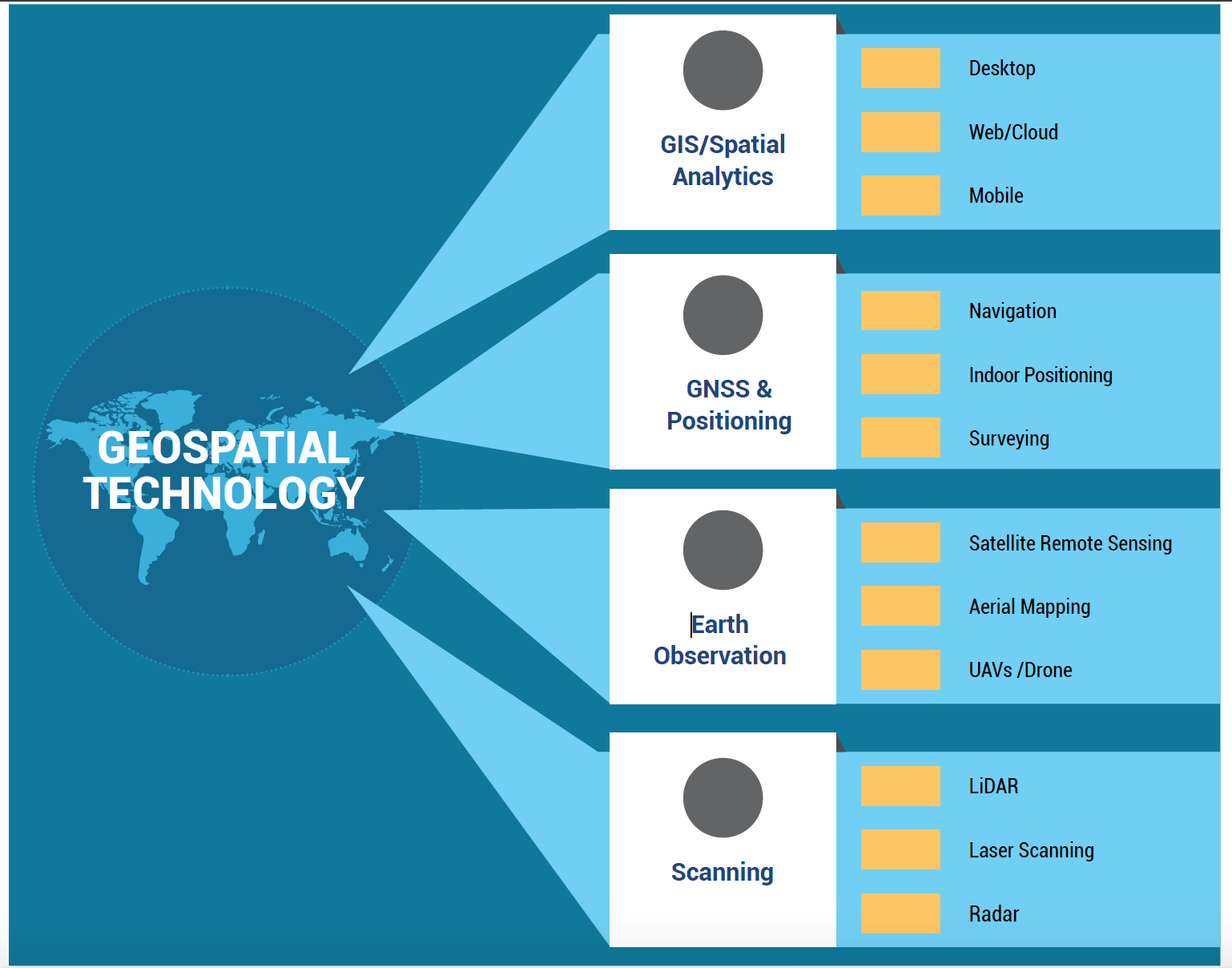

During the lockdown, I wrote a very detailed brief on geospatial technologies for a small set of clients (yes, I am retired but I still do a few one-offs, and next year I’ll be doing 2-3 guest keynotes at some tech events). So I shall crib bits and pieces from that masterpiece 🙂 Oh, and a special shout-out to Andrew Wiseturey, a “map guy” at Apple, for his help.

The term geospatial technologies is used to describe the range of modern tools contributing to the geographic mapping and analysis of the Earth and human societies. These technologies have been evolving in some form since the first maps were drawn in prehistoric times. In the 19th century, the long important schools of cartography and mapmaking were joined by aerial photography as early cameras were sent aloft on balloons and pigeons, and then on airplanes during the 20th century.

The science and art of photographic interpretation and map making was accelerated during the Second World War and during the Cold War it took on new dimensions with the advent of satellites and computers. Satellites allowed images of the Earth’s surface and human activities therein with certain limitations. Computers allowed storage and transfer of imagery together with the development of associated digital software, maps, and data sets on socioeconomic and environmental phenomena, collectively called geographic information systems (GIS).

An important aspect of a GIS is its ability to assemble the range of geospatial data into a layered set of maps which allow complex themes to be analyzed and then communicated to wider audiences. This “layering” is enabled by the fact that all such data includes information on its precise location on the surface of the Earth, hence the term “geospatial”.

In the data slurping/data protection world we see the end result of this technology all the time: Big Tech able to track peoples’ movements via mobile devices both secretly and-not-so-secretly. One of the aspects of the community data collection project I described above was logging every court case and article, world-wide, that involves deceptive and unfair practices used to obtain users’ location data, which is then (usually) exploited for lucrative advertising business. But more interesting is collecting information on a government’s ability to obtain – easily, quickly and cheaply – that precise geographical location at virtually any point in the history of the use of the device. In my U.S. searches, it has been an education on “geofence warrants”, Fourth Amendment probable cause … and bizarre “particularity requirements” I certainly never envisioned in law school.

The Mapillary acquisition

As I noted above, earlier this year Facebook acquired Swedish mapping technology company Mapillary, which collects images from tens of thousands of contributors to build immersive and up-to-date maps. Mapillary aims to solve one of the most expensive problems in mapping: keeping maps updated with “street level data” about signs, addresses and other information that can be observed from the road.

Big companies such as Apple and Google solve the problem by sending out fleets of vehicles outfitted with cameras and other sensors to gather images. But Mapillary crowdsources the images, ingesting pictures contributed from smart phones and other types of cameras, and uses “computer vision” technology to stitch them together into a three-dimensional map. Many consider that information key for self-driving car technology, although for Facebook it would also underpin its products under development like augmented reality glasses and virtual reality headsets.

It does some very cool stuff, all very much sought and admired by the geospatial community. Just two quick examples:

• OpenSfM, a popular computer vision engine for stitching together overlapping images to reconstruct places in 3D

• Vista, a free 25K image dataset labeled for semantic segmentation – one of the largest such open datasets in existence:

But what is really at stake here? Apple, Google, and Microsoft have invested billions into consumer mapping applications and acquired numerous companies to support those efforts. Any of those three behemoths would have felt like natural landing spots for Mapillary. But Facebook? What’s that about?

Unless you are already tapped into the geospatial industry you can be forgiven for not knowing that Facebook actually does do maps. Not only via OpenStreetMap as I detailed above, but such things as an open source, AI-assisted road mapping tool called RapID that is an impressive thing to witness in action.

Still, the mere fact Facebook has dipped its gargantuan toes into the mappy water explains why “geo” is so incredibly important to these platforms. There are three strategic reasons why Facebook made this acquisition and illustrates the importance of geospatial mapping to Big Tech:

#1: It Hurts Google

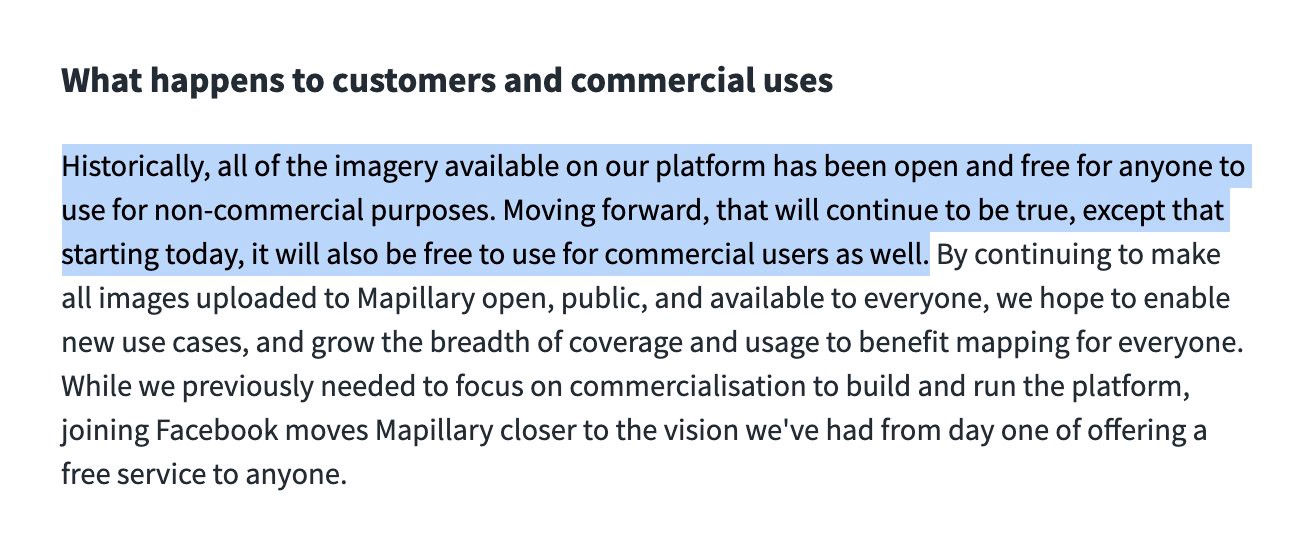

This is the leading theory among pundits. Joe Morrison pointed me to the acquisition announcement on Mapillary’s blog and said “look at this”:

Said Joe:

Previously, you could pay Mapillary for special commercial licensing if, for example, you wanted to use their imagery to inventory street signs and sell that data to municipal governments. Now it seems that Facebook just wants to give it all away for free. If you’re like me and have 100 ideas for how this data could form the foundation of a commercial endeavor, that is rather exciting news. It raises an obvious question, though: why would Facebook want to pay a bunch of money to take a revenue-generating company and turn it into an unabated cost-center?

Answer: to hurt Google. This is a strategy known as “commoditizing your complement” which I noted above. Essentially, if you’re getting your ass handed to you by a competitor with a software or data advantage you can’t replicate yourself, you can use permissive licensing as a weapon to erode that advantage by encouraging the world to collaborate with you. Google itself is no stranger to this strategy; their choice to acquire Android and support it as a free and open operating system for smartphones is an example of this tactic. In that instance, the complement was Apple and iOS.

Google is the clear leader in consumer mapping, and their Google Maps app consistently ranks as one of the most downloaded smartphone apps in existence. For a bunch of companies that sell your private data for incomprehensible sums, the value of a top-ten downloaded app that simultaneously gives you a “legit” reason to ask for the user’s location data AND provides an advertising opportunity is hard to assign a value to. I would guess it’s comfortably in the tens of billions.

Joe again:

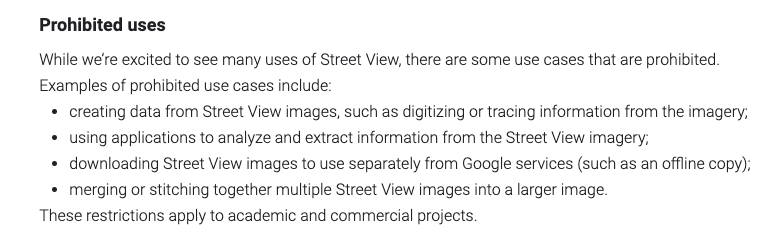

So if you’re Facebook, Apple, Amazon, or Microsoft and you’re wayyy behind Google in this very valuable category…why not all collaborate to simultaneously improve your collective offerings while eroding the value of Google’s? Street View is one of the signature elements of Google’s map offering. And if you’ve ever read the laundry list of limitations on how it can be used by 3rd party apps, you’d appreciate how jealously Google guards it, as follows:

#2: It Complements Their Augmented Reality Business

In a now famous leaked internal memo from 2015, Mark Zuckerberg laid out Facebook’s strategy for investing heavily in the emerging field of VR/AR. It boils down to an obsessive fear of missing the next great platform shift. Facebook survived the move from desktop to mobile by aggressively investing in mobile well before it was obvious that shift would make or break all social media companies. And while VR/AR may seem like a curious plaything now, the risk to Facebook of getting a slow start during another tidal platform revolution is much greater than their fear of being mocked for being too early.

These are not my ideas. Ben Thompson laid them out in exquisite detail in this blog post.

How does street level imagery fit into this strategy? Well, the same week this acquisition was announced, rumors began swirling that Google was testing out adding AR objects/markers to its street view imagery:

Facebook’s $2B acquisition of Oculus showed they were serious about the entertainment side of AR/VR, but I suspect their plans are much broader. Eventually, Mapillary might become one pillar of a suite of tools and data aimed at commercial uses for the technology. The fact it’s free to develop on top of for commercial use cases would certainly make recruiting an ecosystem of 3rd party developers to build value-added applications alongside the imagery much easier (and is clearly not something Google is prioritizing with their current licensing scheme).

And why am I harping on augmented reality? Because of the future of tech. Looking at screens and pecking at keyboards will surely seem quaint by 2030. Just like GPT-3 and its developing derivatives will enable our ability to mine and augment our collective intelligence. There is so much I need to write about this but I’ll save it for 2021. Well, God willing and the crick don’t rise.

#3: It Supports Facebook’s Place Data Generally

Lest we forget, Facebook is in the business of knowing who you are, where you are, what you like, and what you don’t. If you discover a new restaurant through Instagram, and then you leave that platform to open Google Maps and read reviews of that restaurant, Facebook (or the Facebook company or whatever they’re calling themselves now) has just lost a very valuable interaction.

But what if street level imagery and supplementary data like reviews were built directly into Facebook’s products or at least resided somewhere on a Facebook property that could be linked out to? That at least would keep users in their scrupulously measured web of control. Facebook’s company pages don’t offer any kind of street level view (whereas Google’s company pages certainly do) and they link directly out to Google Maps, which I imagine feels like waving a huge white flag of surrender to whoever the product manager is for Facebook pages:

Facebook links out to Google Maps in their own product.

If you’re Facebook, I would guess that sometimes it’s easier to negotiate buying a company outright than it is to negotiate a custom licensing deal that is orders of magnitude larger than any other deal that vendor will ever see in the life of their company. Because of their scale, the value of a particular data asset to Facebook may be entirely dislocated from the rest of the market. At a certain point, you just have to ask yourself, “Instead of buying that, why don’t we just buy them?”

Before I conclude with my wrap-up on geospatial technology, a few words on the “Data For Good” projects with which I was fortunate to work here in Europe.

In the earlier days of the coronavirus pandemic, an animated map from a company called Tectonix went viral. It showed spring breakers leaving a Florida beach to return to their homes across the U.S., as a series of tiny orange dots congregating on a beach in early March scattered across the country over the following two weeks. “It becomes clear just how massive the potential impact of just one single beach gathering can have in spreading this virus across our nation,” the video’s narrator said. “The data tells the stories we just can’t see.”

Most people were horrified but health experts saw an opportunity. How we move about in our communities – where we go and how often – greatly affects the spread of COVID-19. And few know our whereabouts better than Facebook and Google. So, in an effort to help researchers combat the pandemic, the two companies made their troves of GPS-based mobility data available. The data comes from users who opt in to location services on the companies’ platforms and is provided for public health use in an aggregated, anonymized way. Such data is vital to public health researchers’ efforts to understand trends in population movement and predict the spread of the disease, which is caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Local government officials can use the data to make informed decisions on travel and social distancing interventions.

Both Facebook and Google are providing information about where people are going, but the companies differ in the way they are releasing the information. Facebook, through its program, provides mobility datasets and maps directly to researchers upon request. Facebook generates the data in file formats that support epidemiological models and case data. Laura McGorman, policy lead for Facebook’s program:

“We’re sharing the data in a way that public health researchers can use. Once a researcher signs a license agreement, they can request data through our mapping portal and get it the next day. The mobility datasets let researchers look at population movement between two points, movement patterns such as commutes, and whether people are staying close to home or visiting many parts of a town. Almost anywhere across the globe”.

Scientists have used Facebook’s data in several ways over the last few months. The program first became well known when scientists used Facebook’s mobility data to study how social distancing measures and a stay-at-home orders have affected movement near Seattle, Washington in the U.S. They found that population movement indeed declined, which led to reduced transmission of the virus. We used it in Italy to analyze how lockdown orders affect economic conditions and create an economic segregation effect.

Google launched a mobility tracking tool called “COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports”. The web-based tool is available freely to the public and provides insights on how communities have reduced or increased their visits to certain types of places. The public can go to the website and choose a region, such as a state or country. The tool then generates graphs on a downloadable PDF displaying the percentage change in visits over the last few weeks to places such as retail stories, pharmacies, parks, places of work and public transportation hubs in that region.

Example: in Athens, Greece over the summer, before the government tightened lockdowns, people had reduced their visits to grocery and pharmacy stories by 27% and to other retail locations by 45%. Visits to area parks and waterfronts increased 64%. In a blog post highlighting the resource, Google executives wrote that they believe the mobility reports could help shape business hours, inform delivery service offerings, or indicate a need to add additional buses or trains to a particular public transportation hub. The company pulls the data from Google users who have opted in to location tracking services. The information is aggregated and anonymized, and does not provide real-time data in an effort to protect privacy.

Final thoughts

Your phone is the ideal tool for advertisers and data brokers, both as a means of collecting your information and serving you ads based on it. This is usually done through software development kits, or SDKs, which these companies provide to app developers for free in exchange for the information they can collect from them, or a cut of the ads they can sell through them. When you turn on location services for a weather app so it can give you a localized forecast, you may be sending your location data back to someone else.

I must assume even the most absent-minded smartphone user is probably aware that these apps keep tabs on where they go. Many apps wouldn’t work without location data. But few realize just how often that location tracking is happening – even when it’s not necessary, even when their apps aren’t being used, and, increasingly, even when a user isn’t even carrying their phone. Tracking you across the map isn’t always about improving user experience, of course, but rather about better understanding who you are and what kind of advertising to show you. If, for instance, a company knows that you’ve just stepped foot in one of their stores, they might start targeting you with ads touting a sale.

It’s hard to dispute the value of a good sale, but data privacy mavens say location tracking raises all sorts of privacy concerns. Not to mention that using the GPS will drain your smartphone’s battery faster. Should app makers know where we live, where our children go to school, where we go to get away from it all? And if so, how much should they tell us about it?

As I have detailed in numerous posts, location tracking is quietly, sometimes surreptitiously, baked into the web’s modern data collection regime. Google and Facebook have created a network of commercial surveillance with their tracking technologies. The practice of third-party tracking on websites has become so widespread and complicated that special software is needed to understand and track this modern data collection regime. For my most recent post with links to other pieces that will get you started on coming to grips with this please click here.

What we have seen in recent years is significantly enhanced information sharing and networking capabilities among smartphone users, advanced by geospatial technologies which have undeniably permeated almost all aspects of modern life in our society. Social media apps are increasingly location-based, providing analysts with access to a wide range of shared spatial data, such as check-ins, geo-tagged images, video clips or text messages, or reviews of businesses and other localities.

Now, there is a positive impact. Based on these data, research studies provide valuable insights into spatio-temporal aspects of marketing, event detection, political campaigning, disaster management, migration, transport, natural resource management, human mobility, urban planning, tourism, epidemics, and communication. But let’s ignore “the good” for the moment.

This has all led to the creation of a new discipline I wrote about before – geospatial data science. It is a transdisciplinary field that extracts knowledge and insight from geospatial big data using high-performance computing resources, spatial and nonspatial statistics, spatiotemporal analysis models, GIS (Geographic Information Systems) algorithms, machine learning methods, and geovisualization tools. It is also why we’ve seen the emergence of a geospatial cloud and the building of a comprehensive cyberinfrastructure.

For “The Horsemen of FAAMG” .. Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google … its meant a seamless technology stack which includes a geodata hub for sharing assets and facilitating community engagement, cloud services, online analytic tools, real-time big data processing, and a nice set of presentation options. “Location intelligence” in the trade.

And while location intelligence can be gleaned from social media enriched with locational clues, mined to a high degree, developers have realized that advanced geospatial / geographic information systems are foundational and not an add-on so they need to be baked into operating systems.

Even so-called “anonymized” location data – without our real-life name attached to it – can help paint a detailed portrait of a user and their habits, or even crack open their entire identity. Like the National Security Agency, which gathers billions of records a day on people’s cell-phone locations across the globe, developers realized there is a lot to be gleaned from users’ frequented locations and movement patterns. For app developers and ad targeters, this locational awareness became “the stuff of the future” as one data scientist put it to me.

Yes, in some cases “location services” can be turned off but most location data collection cannot. For details, see the link to my post a few paragraphs above. That’s because your device will periodically send the geo-tagged locations of nearby Wi-Fi hotspots and cell towers to Apple or Google or your mobile service provider to augment their crowd-sourced database of Wi-Fi hotspot and cell tower locations. If you’re moving in a vehicle, a GPS-enabled iOS device or Android device will also periodically send GPS locations (and travel speed information) to be used for building up their respective crowd-sourced road-traffic database. Allegedly this crowd-sourced location data is “anonymous and encrypted”. It doesn’t personally identify you.

NOTE: as Bruce Schneier has noted a few times on his blog, identifying people from mobile phone location data is pretty easy. Using “mobility traces” – the evident paths of each mobile phone – from only four locations and times were enough to identify a particular user.

Compare: in the 1930s, it was shown that you need 12 data points to uniquely identify and characterise a fingerprint.

Read all the underlying notices and documentation from any of these Horsemen and you’ll find similar language:

“By enabling Location Services for your devices, you agree and consent to the transmission, collection, maintenance, processing, and use of your location data and location search queries by xxx, its partners, and licensees to provide and improve location-based and road traffic-based products and services.”

Reality? Most users have little choice here. Many apps simply can’t function without activating location services in some form.

Like many other data companies, Google follows users across the internet with web cookies that track IP addresses, which allows the service to make pretty informed guesses on user locations and habits. The tech giant also uses what is known as “implicit location information,” which is when Google interprets a search for a specific location (“Empire State building restaurants nearby,” for instance) as evidence the person will be visiting the building; then targets related ads at the user based on this information. (However, please note both are being “tweaked” a bit to do an end-around privacy laws).

The motherload: Google has access to about 70% of U.S. credit and debit card transactions through partnerships with data companies. After a user clicks on a merchant’s digital ad, Google can determine if that person purchased something in that merchant’s bricks-and-mortar store; that could help persuade merchants to spend more on ads. Google has said it would “match transactions back to Google ads in a secure and privacy-safe way, and only report on aggregated and anonymized store sales to protect your customer data.” Lots to unpack here. Fodder for another post.

Google had also managed to collect user locations in more surreptitious ways. As I noted in a blog post last year, Google collected the physical addresses of nearby cell towers with which Android users’ phones were communicating for everyday text, call and app usage. Gathering data from several cell towers effectively allows Google to triangulate a user’s cell signal, and thus determine an approximate location – even when users have location services turned off or have removed their SIM card. Google said this data was not stored, and shortly after it hit the media, it announced it would end that data collection.

* * * * *

The start of all this must be the primary building block, the SDKs (software development kits) which I noted above. They themselves are not trackers, but they are the means through which most tracking through mobile apps occurs. Simply put, an SDK is a package of tools that helps an app function in some way. Apple and Android offer operating system SDKs so developers can build their apps for their respective devices, and third parties offer SDKs that allow developers to add certain features to those apps quickly and with minimal effort. The name of the game for the past dozen years has been to make it as easy as possible for people to develop apps.

SDKs may also help apps communicate with third parties through what is called an application programming interface, or API. Using the Facebook Login SDK as an example again, the SDK helps the developer build and implement the sign-in feature in their app, while the API allows the app and Facebook to communicate with each other so the sign-in can happen. As I have written before, we’ve now got all these third-party APIs and libraries that have been introduced into this ecosystem, whether it’s for advertising, to connect to social networks, or for analytics purposes. This ecosystem has become extremely complex, and the data flows that result from all this are extremely diverse.

Yes, we have privacy laws floating around the U.S. and Europe but tracking via SDK is firmly, perhaps inextricably, entrenched in the app ecosystem (in 2019, companies spent $190 billion on mobile ads). In this way, it’s similar to the internet. Pretty much everything we do online has been tracked and monetized since the start. Because apps are on the device itself, rather than accessed through a website – and because we now use apps for so many different things and carry the device they’re on around with us throughout the day – they’re able to collect a ton of information about us.

Location data gets the most attention because it feels the most invasive. But there are plenty of other ways to track you or make inferences about who you are to target ads to you. And companies want to put their SDKs in as many apps as possible in order to collect as much information from as many people as possible. Even developers may not know (or care) when and how their users’ privacy is being invaded. But they’ll “tweak” the SDKs as necessary to meet requirements – privacy issues or laws or otherwise.

And with 5G (the short form for “fifth generation mobile network”) on the horizon … quite unlike any of the previous generations in a way that it is unlikely to be defined by any single technology … things will get worse (better?). Often referred to as “the network of networks” because of the way it will bind together multiple existing and future standards, including the current LTE 4G networks, 5G will be way more fast and reliable with greater carrying capacity. 5G will accelerate the move towards digital as a transformative ecosystem that combines Big Data and Cloud, virtualization and augmentation, automation and intelligent machines, distributed computing and artificial intelligence, and insights from data that is generated by billions of connected devices.

And geospatial technology will be the key to all of this. So fasten your seatbelts.