A new breed of researcher is growing in number – turning to computation to understand society

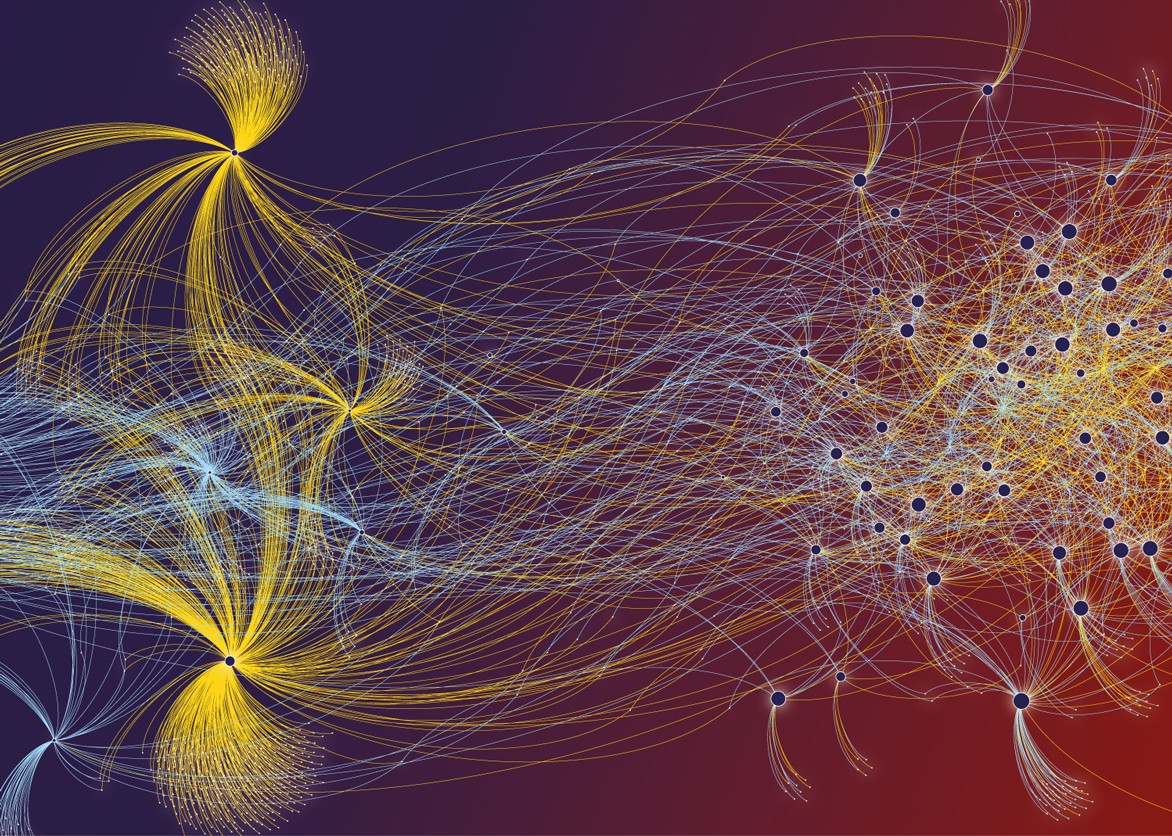

Scientists have been studying data from thousands of social-media users to analyse clusters perpetuating extremism

18 November 2020 (Chania, Greece) – In 2007, a small group of scientists with big ambitions convened a meeting at Harvard University to discuss the emerging art of social-science data crunching. They wanted to apply their skills “to change the world”. During his talk, political scientist Gary King at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said that the deluge of digital information will make it possible to learn far more about society and to eventually start solving the major problems that affect the well-being of human populations. (There is no link to the 2007 event but it is noted and summarised in a piece by Gary King here).

By then, a smattering of computational social-science studies (CSS) had already been published. A 2006 study had looked at the role of social influence on the popularity of music by creating an artificial online music market used by 14,341 people. The participants chose songs to download, sometimes with and sometimes without information about how popular those songs were among their fellow market users. The study found that the popularity of a song became harder to predict the more that users were influenced by others’ behavior, offering one explanation for why it is difficult to predict a runaway success.

Two years later, a study analysed the movements of 100,000 mobile-phone users over six months, and found that people travel in simple and reproducible patterns.

The authors of that study could calculate the likelihood of finding an individual in any particular location, and suggested that identifying similarities in travel patterns across a community could help with urban planning, understanding the spread of disease or preparing for emergencies.

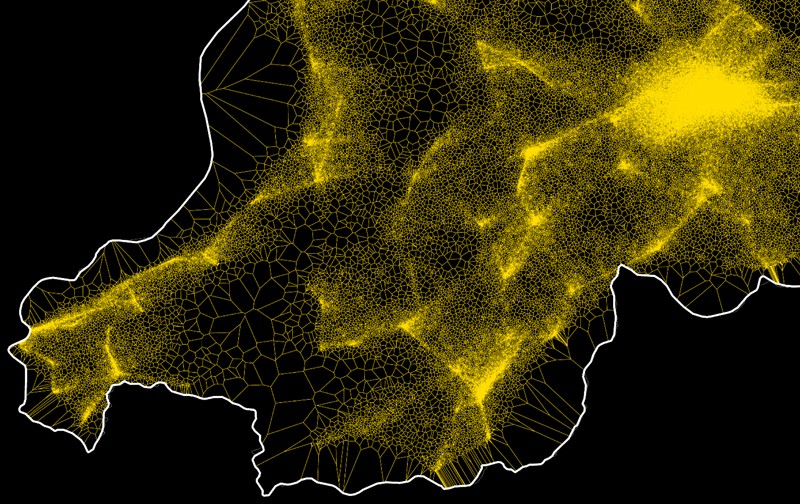

In a recent study, mobile-phone data from 1.5 million users in Rwanda helped infer pockets of wealth and poverty (darker areas are poorer)

In a recent study, mobile-phone data from 1.5 million users in Rwanda helped infer pockets of wealth and poverty (darker areas are poorer)

2008 was also the year that Wired, the technology magazine, published an article arguing that the era of big data would spell an end to theory across the sciences. Although widely criticized as an oversimplification, the article struck a nerve: more than a decade later, social scientists repeatedly invoke the Wired article as a signal that the relevance of social-science theory was under attack. That article remains one of the most cited articles on the “birth” of the Big Data era.

Today, computational social scientists are exploring massive and unruly data sets, extracting meaning from society’s digital imprint. They are tracking people’s online activities; exploring digitized books and historical documents; interpreting data from wearable sensors that record a person’s every step and contact; conducting online surveys and experiments that collect millions of data points; and probing databases that are so large that they will yield secrets about society only with the help of sophisticated data analysis.

Over the past decade, researchers have used such techniques to pick apart topics that social scientists have chased for more than a century: from the psychological underpinnings of human morality, to the influence of misinformation, to the factors that make some artists more successful than others. One study uncovered widespread racism in algorithms that inform health-care decisions, another used mobile-phone data to map impoverished regions in Rwanda.

The biggest achievement has been the slow shift in thinking about digital behavioral data as an interesting and useful source.

Not everyone has embraced that shift. Some social scientists are concerned that the computer scientists flooding into the field with ambitions as big as their data sets are not sufficiently familiar with previous research. Another complaint is that some computational researchers look only at patterns and do not consider the causes, or that they draw weighty conclusions from incomplete and messy data — often gained from social-media platforms and other sources that are lacking in data hygiene.

But the barbs fly both ways. Some computational social scientists who hail from fields such as physics and engineering argue that many social-science theories are too nebulous or poorly defined to be tested. This all amounts to a power struggle within the social-science camp. Who in the end succeeds will claim the label of the social sciences.

But the two camps are starting to merge. The mutual respect is growing. During a CSS webinar last week sponsored by Science magazine and Microsoft, social scientists readily admitted that using observational data, experimental designs, large-scale simulations, and mapping complex networks greatly improved the understanding of important phenomena, ranging from social inequality to the spread of infectious diseases. And the science crowd said it is important to understand the sociology of knowledge and cultural sociology, as well as emotions, to see the big picture.

NOTE: There has been a proliferation of CSS conferences, workshops, and summer schools across the globe. For a very good start, I highly recommend the program on computational social science methods offered through Coursera which you can access here.

The computational revolution

Big Data has only been ascendant. And we are certainly reminded of the similar changes in biology during the 1990s, when high-throughput techniques began generating reams of data about DNA sequences and gene expression. There was this avalanche in new data that required thinking about data in a very different way.

But many conventional social scientists are still unimpressed by the initial fruits of this “revolution”, and find some of its methods questionable. Sceptics viewed studies of social media as experiments conducted on thousands of unknowing and unconsenting participants. Then in 2018, news broke that the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had gathered data from millions of Facebook accounts without the consent of their owners. The aftermath of the scandal continues to bring added scrutiny and scepticism to social-media research, and some scientists have had their projects stymied as platforms institute new privacy policies.

The field was also stigmatized by early papers that addressed “toy” problems – questions that could be answered from the data, but did not address long-standing, fundamental issues in the social sciences, such as how to tackle inequality or influence public opinion. There were lots and lots of “Twitter studies” in the beginning that I think social scientists were not very excited about. Some have argued that the embrace of toy problems was at least in part the product of a young field finding its feet. As analyses have become more sophisticated and data sources more diverse, the field has started tackling more important issues, such as the roots of discrimination, inequality and radicalization. Only now are we getting the kind of data that allow us to look at the big issues.

There are some fascinating recent mobile-phone data studies that suggest humans stick to simple, predictable movement patterns

Last year, for example, researchers from public health and from behavioral economics used health-care records for more than 50,000 patients in a US health-care system to analyse a commonly used algorithm that recommends people with complex medical needs for extra supervision and health interventions. The team used modelling to show that the algorithm was systematically discriminating against Black people – potentially influencing the care of millions of people. The researchers then used knowledge of health-care disparities in the United States to track down the sources of that bias, and to suggest ways to remove it.

For example, algorithms shouldn’t assume that the amount spent on an individual’s health care is a good proxy for how much care they need: because of unequal access to health care, less money is typically spent caring for Black Americans than white Americans, even when they have the same health-care needs.

But access to good data isn’t the only challenge: scientists migrating from physics or computer science stand accused of failing to examine the theories that social scientists have formulated to explain human behavior. Giulia Andrighetto, who trained as a philosopher but is now a computational social scientist at the Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, part of Italy’s National Research Council in Rome:

“They tend to look for patterns. But typically they don’t look for the mechanisms through which those behaviors are generated.”

To do that work requires a firm grasp of social-science theory.

The first major conference bringing together the two approaches was scheduled this year but was cancelled due to COVID-19. It has been rescheduled for the end of 2021. Also, universities are getting in the swing. George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, has established the first dedicated department, for instance.

But a lack of communication is still evident. There was a fascinating study published last year in which researchers mapped out a network of online hate groups on the Facebook and VKontakte platforms, and showed how the structure of the network changed over time. But the study was criticised because the physicists and computer scientists who carried out the study failed to cite key social-science studies in their work, and as a result, their interpretation of their findings wasn’t as rich as it could be. They also surveyed too few social-media platforms, when past research had shown that hate groups follow charismatic leaders across many domains. And the team came to what many thought was a dangerous conclusion: that social-media platforms could try to steer discussion in hate groups, for instance by creating false accounts or engineering in-fighting between hate clusters. This could backfire by increasing the volume of discussion in the group and boosting its ranking on search algorithms. A better strategy, said critics, would be to check the spread of hate messages by having search engines limit the visibility of such groups.

But the researchers fought back. They said they cited the most relevant references. And as for search algorithms, social-media companies have the power to manipulate them just as they are doing now to suppress the prominence of anti-vaccine and COVID-19 misinformation pages and groups. All of them have studied misinformation, conflict and extremism and said they get complaints every time they publish a high-profile paper.

But they have the momentum over regular social scientists. Many organizations and policy makers like the quantitative nature of this work and the ability to model what impact interventions might yield. And despite the CSS crowd wanting to “play nice in the sandbox”, there is a growing scepticism of the importance of theory to these projects, a feeling that many social-science theories are too nebulous to be tested using big data. The idea of social capital, for instance, is sometimes defined as the shared understanding and values in a society that allow individuals to work together. The original formulation of this concept of social capital is just too vague to be tested. How could I measure it?

Given the current state we are in, I do not to see any social sciences changing the world. And too often we have situations of academic researchers merely chasing publications rather than real-world solutions. The real job? Put the paper out there – and then figure out how to translate them into meaningful interventions in the real world.