The California measure is likely to spur economic growth, has risks … and brutal truths have been ignored

12 November 2020 (Chania, Greece) – California’s Proposition 22 (known as Prop. 22 but formally on the ballot as the “App-Based Drivers as Contractors and Labor Policies Initiative”) exempts employers from having to apply employee minimum wage and benefits requirements to gig workers. It passed easily Wednesday, a win for the likes of Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Postmates and Instacart’s owner Maplebear, which united in a $224 million marketing push in favor of it.

One of the most significant benefits for the sector is that Prop. 22 makes it easier to start and run an app-based business. I was following the Proposition over the last year as part of the research for my monograph on the struggle, and sometimes futility, of controlling or regulating technology in the modern world.

Marketers have long known that the voice of the average person can be a powerful thing. But if 2020 had a textbook case, it might well be a man known to millions of viewers only as Marcell H. He was one of 55 million Americans that the Bureau of Labor Statistics classifies as a gig worker. Marcell, who works for delivery app DoorDash, lives with his elderly grandparents, both of whom require a great deal of physical assistance. One day, his grandmother fell down at home and called her grandson on his cellphone.

“I was able to clock out of work to go and pick her up off the floor. Had I been in a different job, I would have been in trouble, written up or gotten fired for pulling my phone out during work. I wouldn’t have been able to be there for my grandmother.”

Marcell was one of the scores of real-world Californians whose testimonials appeared on the Facebook page for Yes on 22, the political coalition assembled to mass voter support behind the ballot measure. The measure notched 58% of the vote, winning easy passage.

For America’s leading ride-sharing and delivery apps, the win wasn’t just good news for their bottom lines; it was a literal return on investment. More than 90% of the $224 million spent on the marketing effort behind Prop. 22 came from the corporate coffers of Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Postmates and Instacart’s owner Maplebear, according to the Los Angeles Times. Last month alone, the Facebook component of the campaign rang up a tab of $3.7 million, more than was spent by either of the presidential campaigns.

Lyft president John Zimmer told the Washington Post:

“The measure’s passage was a turning point for the future of work in America. The future of work is more secure. Prop 22 represents the future of work in an increasingly technologically driven economy.”

Zimmer’s observation also raises one of the more important business-oriented questions to swirl out of the 2020 election: will the precedent set by Prop 22 have broader implications for brands and contract workers overall? Many experts believe so, though not all of the implications are positive.

A possible spur to growth

The foremost likely result is that the passage of 22 will not only open the door for new app-based startup brands but also make it easier for existing startups to access potential funding. For people who want to get into an app-based business, you suddenly have a legitimized business model. If you’re looking to invest in this market or develop a business that wants to get into this market, this is a massive boost in confidence. And with the legitimization of that business model, the economy (well, theoretically) will be able to count on the sort of job growth that’s essential in a pandemic-fueled recession. That’s the argument: this decision will have impacts spread throughout the country. Unemployed workers want as many options as possible to bring in money to their families. With a precarious economy, the economy in tatters and Covid continuing to surge, gig workers will rise to the forefront of many companies’ staffing choices.

As I have noted before, the American economy was moving in the contract worker direction long before the pandemic and it will continue. The U.S. Bureau of Statistics (verified by the ADP Research Institute) has noted that the share of gig workers at U.S. businesses swelled 17% in the period 2010 to 2019.

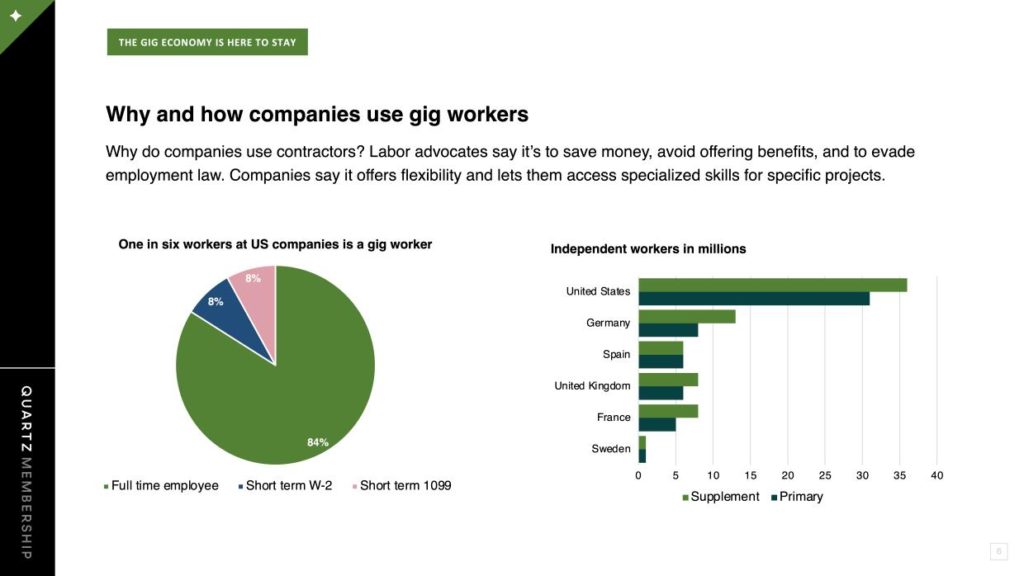

There is much that I could discuss here such as how this gig economy has generated positive spillover effects by putting underused assets to work and expanding economic opportunity, plus negative externalities like weak regulation which has certainly helped the sharing economy grow. Just a few points. This chart from a Quartz webinar is interesting:

The gig economy spans beyond ride-sharing and food delivery and encompasses a vast array of professional services, however a standard definition for the gig economy does not yet exist. As a result, gig workers are defined by a plethora of names and various distinctions for full-time or part-time workers.

Gig workers represent 25%-30% of the American workforce according to surveys conducted by the McKinsey Global Institute, Freelancers Union, and MBO Partners. And the real number may be larger due to undercounting. Approximately 256 million workers participate in the global online platform economy according to the Online Labor Index but this number doesn’t come close to including all “gigs,” as most informal jobs in developing economies aren’t coordinated through online platforms.

The rise of gig work can be attributed to the growth of online platforms like Uber and Lyft, which made it easier to buy and sell contract work. Investors have taken note, pouring billions of dollars into these platforms. The transportation-based services Uber, BlaBla Car, DoorDash, and Careem have raised $34 billion in private and public funding between them.

These platforms have also become the poster children of the emerging fight over labor rights for gig workers. Labor advocates argue that companies use gig workers to save money, to avoid offering benefits, and to evade employment law. Companies say it offers flexibility and lets them access specialized skills for specific projects.

While California’s Proposition 22 went in favor of Uber and its peer companies, other parts of the world have resisted. In the UK, Uber’s fight to reclassify workers has reached the supreme court and UberEats drivers in Japan have unionized.

If you want a deep dive which frames all the issues, the best book I can recommend on the whole gig economy subject taken from multiple angles is The Sharing Economy

And frankly, the pandemic has already been forcing people to find their own way and create their own independent businesses. This is the way the world is going now. The question is how legislation needs to support those people trying to find a way forward with their lives. Has California simply caught up with how the working world has changed?

Political stances now might be safer to take

Given that Prop 22 represented a touchy political issue in what is already a highly politicized national climate, it’s also conceivable that its passage will embolden brands to take public positions on hot-button issues. Companies like Uber and Lyft used both a carrot and stick approach in their public push for Prop 22. On one hand, the measure would benefit their contractors by giving them flexibility to work as much or as little as they want. But they also made their share of threats, warning that if Prop 22 failed to pass, the result would likely be layoffs, price hikes or even companies leaving the state.

And despite the support the measure received, an estimated 4.8 million people voted against it.

Now that these brands have stacked their chips on the political felt and won, other brands may feel more comfortable doing the same. I do see this ‘victory’ as an affirmation for other companies that are becoming more socially and politically active. I expect we’ll see more brands make public appeals especially in the tech/privacy and monopoly challenges being raised by regulators and citizens groups.

BUT … it’s these very stances that may also prove a liability for the brands going forward, at least so far as their brand images are concerned. So while I do think this will embolden other companies with new business models to really look at ways that they can engage people who want to be part of the gig economy, one of the things they should be aware of, while they tout this as a victory, is potential consumer backlash. Some consumers may defect, especially the ones who really care about ensuring that gig workers have the full protections that those of us who are employees of companies have.

Uber’s business model is innovative. It is regulatory arbitrage. Just like AirBnB. But if you scan analysis and comment on LinkedIn (the better place to read for issues like this) you’ll read “the nerve of Uber!!” But I am aligned with Chris Donegan, a Linkedin mate, who noted:

It is no surprise that the company took legal / lobby action to change the law when threatened. It is their right to do so. I am sure that many drivers consider themselves independent contractors and may have multiple jobs. There are undoubtedly others who are in effect employees. As technology evolves so laws get re-written or re-interpreted. U.S. labor laws are quite different from those in the EU. The notion of an “employee at will” for example is a unique US creation. In this context the emergence of Ubers business model and this ruling is quite understandable.

But Nick White (another uber Linkedin mate who has set me straight on many an issue) has an equally valid point:

Innovation is one word that has been abused into extinction. Regulatory arbitrage is not innovation. The ruling just shows what $200 million can buy and it is no surprise that in the land of the greenback nobody really cares that the regulation never catches up. Uber’s model is simple. They collude with customers to screw the very people who actually deliver the service and often as a last resort. These companies are to be reviled like tobacco companies. Uber will be in the same verboten ESG category as just a another low-life business.

And if you take it step further, the digital age is not concerned about humanity. It should be, but it is not. As one commentator noted:

How did we go from valuations of hundreds of millions to billions and now trillions? Eliminate the biggest expense on your balance sheet: people. Proof that these companies are not about innovation, but are wrapping themselves in the cloak of “technology” to further exploit the ever-expanding working precariat.

Great point, and it applies to other industries and companies. Like Uber and Lyft, these companies exist only because of the massive cheap capital out there desperately seeking out any kind of speculative return. Uber has effectively isolated the value contributors from the revenue generators by veiling their pay scale behind algorithms, outsourcing “employee” email support. As many have noted, there is room to disrupt this market with actual value creation for consumer and worker (the old taxi model surely needed an update) but this isn’t it.

And us wee consumers? Ah, the dilemma: we need *Uber like services*, although we don’t want or like the *Uber company*. But that is the same for many incarnations in other digital segments we need.

FOR MY NEW READERS: this ballot initiative is one issue I address in a much longer piece “What the U.S. election taught us about technology, and our attempts to regulate it” which I hope you have an opportunity to read.