Algorithmic fashion is a thing: fashion houses have been increasingly giving consumers something that consumers have already suggested – more or less implicitly – to be wanting. My dive into a few of the aspects.

16 October 2020 (Crete, Greece) – Years ago, when we were living in New York City, my wife worked for Versace. I became fascinated by the fashion industry. I attended numerous “handbags at dawn” events in New York City, and then London (the events were actually titled Intellectual Property and Fashion Economics, but informally called “handbags at dawn”) and were a 2-day conference with experts in fashion economics, fashion marketing and consumption, and copyright law. Later they would add an e-discovery component.

NOTE: the expression “handbags at dawn” is derived from the better known and more masculine phrase “pistols at dawn” which relates to duelling, and is applied to various forms of non-violent confrontational situation between two people. A similar phrase is “pistols at ten paces” which was feminised to become “handbags at ten paces”. Both this expression and “handbags at dawn” emerged in the 1980’s by way of describing confrontations between UK professional footballers, cat-fight like expressions of the mid-match frustrations and disagreements footballers would generate when players were obviously bound by rules to refrain from physical violence on the pitch. It was a natural pick-up by the fashion industry which began using it in 2002 for the conferences noted above.

It also owes some credit to a long-running Monty Python sketch:

The fashion industry “handbags at dawn” events ended in 2016.

I eventually added several fashion industry members to my intellectual property client list, and when I ran a EMEA-based legal staffing company I staffed several fashion and IP e-discovery projects for a few NYC and London law firms. Oh, and yes: I received scores of free tickets to fashion shows. My only claim to fame from those shows: I once sat next to Lee Radziwill – but did not recognize her. And truth be told: I was only next to her for 10 minutes. I was in the wrong seat and I had to move. Back 5 rows. Though we did shake hands.

Over the last year, fashion expert Vanessa Friedman (fashion editor for The New York Times) and Marc Bain (fashion editor for Quartz) have been publishing some interesting articles on the pressure on designers to design by algorithm. We know so much about buying habits and likes, and the result is an insidious bias toward giving people what they have already indicated they want. It may be safe, and easier to sell, but it’s antithetical to the whole point of fashion, which should be about giving people what they never knew they wanted – what they couldn’t imagine they wanted – until they saw it.

But while it’s good for designers to get out of their comfort zone, trying to please too many people too much of the time can lead to confusion. It tends to lead to all sorts of seemingly random directions. It can be hard to follow.

So it has become quite commonplace for fashion houses to produce garments that consumers already want, through “profiling”. As explained by Friedman:

It will not come as a surprise that identification of what we will want, and what we will be eventually given and shop, owes a great deal to our own social media activity, that is the “likes” we give, whom we follow, and the content that we share ourselves. Is this data difficult to collect and elaborate? Not at all. There are scores of sophisticated computer programs (algorithms) that act as gatekeepers of all this information to assist the fashion industry by translating all of this information into revenues and personal success of fashion designers. It’s a bit tricky but the results are startling.

Mining social media content

I was able to return to this area of my life because although I am retired, I do receive the occasional request to do some research for old fashion industry clients who are looking for applications of text and visual and data mining (TDM) techniques in various fields, especially fashion, in preparation for a large cross-border fashion copyright e-discovery project.

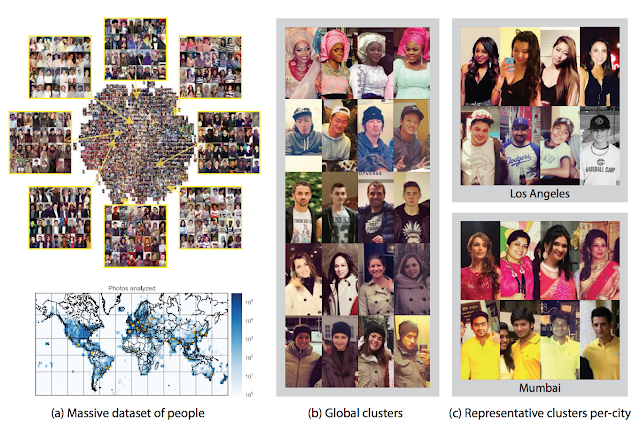

There is a very intriguing study conducted by Cornell University which has become a bit of foundational text. With the aid of TDM techniques researchers were able to mine 100 million photographs made available on Instagram and devise patterns on how clothing styles vary around the world, and tackle the frequency of use of certain garments and colors. By training a machine-learning algorithm, the researchers were able to identify a set of visual themes and study how these would vary by time and place, and also identify the preference for certain colors.

Clothing is a rich, complex visual domain from the standpoint of computer vision, because clothing analysis combines a detailed attribute-level understanding with social context. So you can train classifiers using any number of attributes, and then leverage this training to organize images in order to perform more fine-grained clustering. It is a fabulous way to explore spatial and temporal trends.

For our project, we are developing algorithms for the same approach: developing a visual discovery at scale. It started out to be a “textual” search but then quickly grew as we realised the large-scale dataset of photos allowed us to develop “style clusters” so we could capture a number of useful visual correlations in these massive datasets. And, of course, we are using Python which has become the “go to” programming language, available for almost all operating systems. I can say no more (these nondisclosure agreements are a pain).

The Cornell study is interesting from an anthropological standpoint, but may be even more interesting for fashion businesses in order to understand and even anticipate the next big trend, or the next cerulean sweater (my favorite scene in the movie The Devil Wears Prada):

As explained by the authors of the study themselves:

Individuals make fashion choices based on many factors, including geography, weather, culture, and personal preference. The ability to analyze and predict trends in fashion is valuable for many applications, including analytics for fashion designers, retailers, advertisers, and manufacturers. This kind of analysis is currently done manually by analysts by, for instance, collecting and inspecting photographs from relevant locations and times. We aim to extract meaningful insights about the geo-spatial and temporal distributions of clothing, fashion, and style around the world through social media analysis at scale.

The question that arises from an IP standpoint is whether and to what extent unauthorized mining activities of this kind may be considered lawful.

GRAPHIC: from the Cornell University Study I cited above. This is part of “StreetStyle: Exploring world-wide clothing styles from millions of photos”

Instagram’s Terms

Because of my continuing client work and my writing in fashion and digital media I keep accounts with both Instagram and TikTok. According to Instagram’s Platform Policy, by making content available there, users grant Instagram and its affiliates a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide licence to use any data, content, and other information made available by users or on their behalf in connection with their use of Instagram. This licence survives even if one stops using the platform feature. Users are responsible for obtaining the necessary rights from all applicable rightholders to grant such licence.

It would thus appear that, unless one is an affiliate of Instagram, the licence granted to the platform may not cover the making of annotated datasets containing thousands of images to be made publicly available.

From a copyright standpoint, the extraction and reproduction of Instagram images may pose copyright issues (among other things). One may thus wonder whether and to what extent liability might arise for the making of such restricted acts without permission from relevant rightholders or whether, instead, no permission is needed because of applicable copyright exceptions.

TikTok’s platform and privacy policies are quite different and I will address them in a forthcoming post whose sole focus is on TikTok.

The approach in the US

Under U.S. law, the question would be one of fair use under §107 of the Copyright Act. The fair use assessment requires one to consider – among other things – whether the use made of a work “adds value to the original – if the quoted matter is used as raw material, transformed in the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings – this is the very type of activity that the fair use doctrine intends to protect for the enrichment of society”. That’s from a Harvard Law review article titled “Toward a Fair Use Standard”, an excellent review of the topic. For the Wikipedia summary and a link to the article click here.

In the longstanding litigation over the Google Books Library Project, the 2nd Circuit considered relevant for a finding of fair use also the fact that the search engine “makes possible new forms of research, known as text mining and data mining” by using the Google Library Project corpus “to furnish statistical information to Internet users about the frequency of word and phrase usage over centuries”.

There is substantial case law in the U.S. but I have not had time to do a full read but must for this IP project. However, it suggests that acts of incidental or intermediate copying which do not ultimately result in the external re-use of protectable (expressive) parts of a copyright work (this might not be the case of the whole of the Cornell project) should not be considered infringing, ie such as to supersede the objects or purposes of the original creation.

It may thus be the case that, under U.S. law, the mining of Instagram content – insofar as protected parts of the content mined are not re-used or made available as such – might be considered fair use. That would be so because the goal of the mining activity is not creating a replacement for the original content, but rather extracting information (ideas and facts are not protectable as such under copyright) in order to obtain new information.

Things, however, may be different in Europe, especially considering the limitations that might be envisaged for an EU-wide TDM exception.

The approach in the EU?

While a limited number of Member States in the EU has already introduced (UK, France, Germany and Estonia: see here) or is planning to introduce (eg Ireland) a specific text and data mining exception, in the context of the current copyright reform debate, a provision (Article 3) has been included in the draft Directive on copyright in the Digital Single Market.

In its original formulation, the mandatory EU TDM exception would allow any type of TDM (commercial and non-commercial). However, the catalogue of beneficiaries and the purpose of permitted mining activities would be limited: Article 3 would only apply to “research organizations in order to carry out text and data mining of works or other subject matter to which they have lawful access for the purposes of scientific research”.

As proposed in the JURI Committee Report of the European Parliament, Member States should remain free – despite the introduction of a mandatory EU-wide TDM exception – to retain or introduce TDM exceptions in accordance with point (a) of Article 5(3) of the InfoSoc Directive, this being the legislative basis used to introduce non-commercial TDM exceptions that, as is the case of the UK (section 29A CDPA), do not envisage any limitations as regards the beneficiaries of the exception.

Algorithmic fashion is a thing: fashion houses have been increasingly giving consumers something that consumers have already suggested – more or less implicitly – to be wanting. This knowledge may be acquired manually but also through TDM techniques. These allow to learn much more and much more reliably, not just about things as they are, but also about things as they will be.

From an IP standpoint, all this raises a number of legal questions at the interplay between copyright subsistence, exceptions and licensing. From a fashion perspective, it instead raises the question whether fashion should be about what we want and everything consumer profiling and purchasing habits or, instead, what we didn’t know we wanted … yet.

Fascinating stuff, Greg, thanks for this very insightful article!