U.S. Congressional regulators announce they are ready to bring Big Tech to heel

7 October 2020 (Chania, Crete) – U.S. Congressional lawmakers, who spent the last 16 months investigating the practices of the world’s largest technology companies, said late yesterday that Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google had exercised and abused their monopoly power and called for the most sweeping changes to antitrust laws in half a century. In a 449-page report that was presented by the House Judiciary Committee’s Democratic leadership (I read through it last night and most of today), lawmakers said the four companies had turned from “scrappy” start-ups into “the kinds of monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad tycoons.” The lawmakers said the companies had abused their dominant positions, setting and often dictating prices and rules for commerce, search, advertising, social networking and publishing.

Over the summer I watched the hearing that was part of that investigation – the quizzing of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Apple CEO Tim Cook, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, and Google CEO Sundar Pichai.

Jesus, where to begin. I have been immersed in this area for almost three years as I have been working on a (long delayed) monograph on the regulatory state in the Information Age. Delayed because I realized there has been a hundred year war between monopoly power and democracy. Americans once challenged corporate power, but in the 1970s that old “Watergate Baby generation” rejected this tradition, embraced monopoly, and destabilized politics. I decided we need perspective and an overall arc to explain how we got here. And for a taste, tomorrow I will publish my critique of that recent Netflix travesty “The Social Dilemma” rocketing around the internet that highlights why a dumbed down electorate misses the forest for the trees via an “after school special” that manipulates you with misinformation – as it tries to warn you of manipulation.

After scanning a few news reports and seeing that the subcommittee split along party lines on how to remedy and corral the power of the tech companies, my first thought was it will be an uphill battle to get legislation through. It will fall to the Democrats to do the heavy lifting. The Republicans are merely enraged about whether posts get deleted on social media.

But before I detail my further initial thoughts, let’s look at this committee report monster.

The report itself is over 400 page long (click here). Just as many of you have, I’ve read a bunch of these whoppers from enforcers all over the world, and this one is by far the clearest and most aggressive. The UK report on social media and media networks was also very clear, but no where as aggressive. By the numbers:

* The subcommittee staff went through 1,287 million documents

* They also went through significant quantities of enforcement agency records, and did hundreds of hours of interviews with “more than 240 market participants, former employees of the investigated platforms, and other individuals totaling thousands of hours”

* They held seven hearings, including this past summer’s hearing when they questioned the richest man in the world, Jeff Bezos

It’s an extraordinary document – and let’s remember the investigation was set up to succeed. As I noted after the summer hearing, the Congressional members of the committee had written their summary statements before the hearing had even commenced.

VERY IMPORTANT SIDE NOTE: the key staffer on the subcommittee, Lina Khan, is an experienced journalist, as well as the preeminent scholar of modern antitrust thinking; before coming to the investigation, she had published the legendary law review article, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, which single-handedly undermined the intellectual structure of the current way lawyers and judges handle corporate power.

For a nice profile on the small team of House staffers who led the mammoth investigation click here.

The basic thesis of this report isn’t a surprise, and consists of three basic elements:

1. The subcommittee found that Apple, Google, Facebook, and Amazon are abusive monopolies

2. The report also noted that Obama and Trump era enforcers failed to uphold anti-monopoly laws, which allowed these corporations to amass their dominance.

3. What makes these platforms unusually dangerous is that they are gatekeepers with surveillance power, and they can thus wield “near-perfect market intelligence” to copy or undermine would-be rivals. For Apple the dominant facility is the App store, for Google it’s the search engine, Maps, adtech, etc, for Facebook it’s social media, and for Amazon it’s the marketplace, AWS, Alexa, Fulfillment, and so forth. They exploit their gatekeeping and surveillance power to extract revenue, fortify their competitive barriers, and subsidize entry into new markets.

Over and over, the report just lays into the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission Antitrust Divisions for refusing to enforce monopolization laws and failing to stop mergers, even when they had evidence that such mergers were anti-competitive. The four companies bought more than 500 companies since 1998. However, “for most, if not all, of the acquisitions discussed in this Report,” it says, “the FTC had advance notice of the deals, but did not attempt to block any of them.” What were the priorities of the agencies? “Both agencies have targeted their enforcement efforts on relatively small players—including ice skating teachers and organists—raising questions about their enforcement priorities.” Oops.

I have lots and lots and lots to say but these points will be brief. As many commentators have noted, the subcommittee report is also a deeply political document, explicitly so. How can it not be? The report attacks the way that these corporations finance think tanks and academics, through a combination of direct lobbying and funding think tanks and academics, the dominant platforms have expanded their sphere of influence, further shaping how they are governed and regulated. The platforms also engaged in routine attempts to deceive investigators, and the report is merciless about such attempts at deception.

For instance, the committee asked Amazon for a list of its top ten competitors. The report authors noted that “Amazon identified 1,700 companies, including Eero (a company Amazon owns), a discount surgical supply distributor, and a beef jerky company.” The report has multiple examples of such dissembling, from each company.

The report also notes the coercion they have imposed on commerce. It’s one of the first things the committee noted last year when starting the investigation was how scared businesspeople were to talk to the subcommittee. Investigators found “a prevalence of fear among market participants that depend on the dominant platforms, many of whom expressed unease that the success of their business and their economic livelihood depend on what they viewed as the platforms’ unaccountable and arbitrary power.”

The report is peppered with footnotes of interviews from anonymous customers and merchants who use the platforms. Said several sources, “It would be commercial suicide to be in Amazon’s crosshairs . . . If Amazon saw us criticizing, I have no doubt they would remove our access and destroy our business. We fear retaliation by Apple and are worried that our private communications are being monitored, so we won’t speak out against abusive and discriminatory behavior.”

It’s a sophisticated document, with sections analyzing industry dynamics among voice assistants and cloud computing, as well as presenting better data on the platforms themselves. Facebook, for instance, has over 200 million users in the U.S. just on its Facebook app, and is on 74% of mobile phones, which is new information. Amazon has in all likelihood over 50% of online sales, not 40% as eMarketer puts out. And I learned some new areas of anti-competitive activity, like Google requiring users of Maps APIs to have a Google Cloud Platform account, or credible allegations that Amazon Web Services engaged in “cross-business data sharing.”

And tons of “insider” information. One former Facebook employee noted:

“I was a product manager at Facebook. My only job was to get an extra minute. In any way possible. It’s immoral. They don’t ask where it’s coming from. Legal, illegal or manipulative. They can monetize a minute of activity at a certain rate. So the only metric is getting another minute.”

And here is lots of info on the “gears and wheels and tubes” of how tech works. There’s a terrific section in this report analyzing how cloud computing works (it starts at page 109).

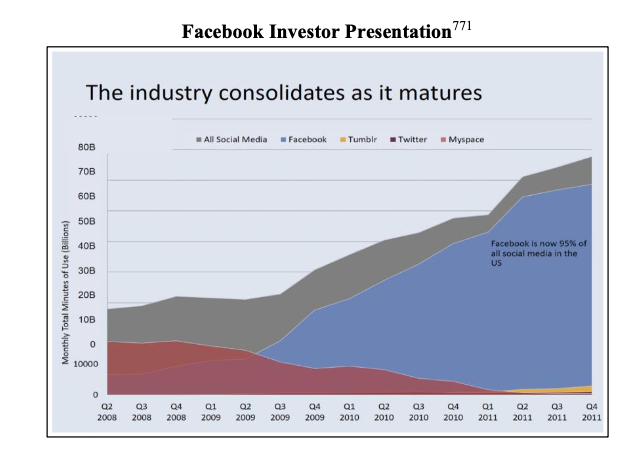

Some cool graphs, too. From an internal Facebook document:

And (brace yourself) some of those Big Tech CEOs last summer …. lied. The report essentially says Zuckerberg lied about how important Facebook’s investment in Instagram have been:

Facebook’s support of Instagram’s growth after acquiring it is overstated. Before acquiring Instagram, Mr. Zuckerberg said that Facebook should “invest a few more engineers in it” but let Instagram “run relatively independently.” Prior to being acquired, Instagram’s internal projections showed the company gaining nearly 88 million users by January 2013, and that its growth trajectory would not be significantly affected by the transaction.

Although Google was the most openly dishonest of the four companies being investigated. Last summer Google CEO Sundar Pichai said (and I replayed my tape) “we don’t have a dominant market share”, then refused to provide market share data, saying “we don’t even collect it”. But, of course, their docs show they do:

In submissions to the Committee, Google states that Google Search “operates in a highly competitive environment,” facing a “vast array of competitors” in general online search, including Bing, DuckDuckGo, and Yahoo! Google also claims that for any given search query, Google competes against a “wide range of companies,” including Amazon, Amazon, eBay, Kayak, and Yelp. Google argues that this broader set of competitors means that public estimates of its share of general online search “do not capture the full extent of Google’s competition in search.”

Despite these statements, Google failed to provide the Subcommittee with contemporary market share data that would corroborate its claims. In response to the Committee’s written request for market share data, combined with several follow-ups from Subcommittee staff, Google stated that the company “doesn’t maintain information in the normal course of business about market share in its products.” After the Subcommittee identified communications where Google executives had discussed regularly tracking search market share data and further developing internal tools for doing so, Google told the Subcommittee that this data is either no longer collected or no longer used for examining site traffic.

Oh, lots more but I’ll save it for my monograph. But as I have noted in previous posts, much of this has been covered by the more astute media analysts:

• From Facebook, we got a look at how the Instagram acquisition looked from the inside.

* From Amazon, we learned that the company calls sellers on its platform “internal competitors” – and may have perjured itself when it told Congress, apparently falsely, that it does not use internal data about individual sellers to develop competing products.

• For Apple, lawmakers talked to a former director of review at its App Store, who told them that “Apple has struggled with using the App Store as a weapon against competitors.”

• And at Google — which the report devotes more pages to than any of the other three companies — lawmakers found that the company had improperly scraped competitors’ websites to gain advantages, creating “an ecosystem of interlocking monopolies” across search, ads, maps, and more.

The key finding of the committee: that “courts and enforcers have found the dominant platforms to engage in recidivism, repeatedly violating laws and court orders,” which “raises questions about whether these firms view themselves as above the law, or whether they simply treat lawbreaking as a cost of business.” The bottom line is that the House Antitrust Subcommittee found, with lots of evidence, that these are aggressive and deceptive predatory monopolies.

In the least, the report lays the foundation of a Biden administration’s anti-monopoly framework, should Biden be elected. But most importantly, the report re-asserts Congress’s role as the central policymaking body in America, seizing control from judges who have re-written case law in ridiculous ways, as well as slothful enforcers.

What does this report recommend, in terms of policy specifics? A bit of a mixed bag with lots of stuff that will be tough to implement, never mind enforce. Basically, the committee wants to fix the problem we have with big tech, make sure it doesn’t recur by changing the laws that led to it, and make enforcement better by pressuring public officials and empowering ordinary citizens themselves to enforce anti-monopoly laws. So the recommendations fall into four buckets, and I thank Casey Myers (who read this section more closely) for this summary:

1. a legislative break-up and restructuring of big tech platforms to restore competition online

2. a strengthening of laws against monopolies and mergers

3. institutional reforms to fix and fund the Federal Trade Commission and DOJ Antitrust Division, and

4. restoring the ability of ordinary citizens to take monopolists to court on their own

The premise of this report repeats what scores of industry analysts and critics have noted before: that the tech sector is simply far too concentrated, and so Congress will have to affirmatively take steps to de-centralize power there. The report notes that there are ample historical precedents, like the financial syndication rules, or the Commodities Clause of the Hepburn Act for railroads, which blocked railroads from owning coal mines.

The report also suggests reinvigorating antitrust laws by reasserting Congress’s role as the central policymaker when it comes to authoring laws, which the courts have gradually encroached on, writing statutes to overrule a host of Supreme Court precedents that have unreasonably crippled antitrust laws on things like pricing below cost or abusing one’s dominant position as a platform, as well as making very clear rules on when mergers can go through and when they can’t.

That last paragraph? YIKES! Anti-trust lawyers reading this can see the enormous complexity. Change areas of law like monopoly leveraging, predatory pricing, essential facilities doctrine, predatory design, ending special antitrust exemption for platforms (Amex), shifting the burden of proof on mergers for dominant platforms, imposing bright line market share rules for mergers, imposing a presumptive ban on future acquisitions by large platforms, imposing a presumption that vertical mergers by large platforms are unlawful, and ending arbitration clauses and re-empowering class action lawsuits? Good luck with that, kids.

BUT … America is a weird place. People change their minds. Norms shift. Just twenty years ago, the idea of gay marriage was politically unthinkable. Today gay marriage is broadly accepted, and young people don’t give it a second thought. Matt Stoller noted in 1995, a majority of Americans didn’t approve of interracial marriage, and today that number is at 8%. But then again, it was hard for most of us to imagine President Trump, until President Trump happened.

Yes, I am still a cynic. I am not getting warm and fuzzy on you. I see norms shifting around monopoly and corporate power, that the anti-monopoly position increasingly seems to be the default. It isn’t that everyone agrees, but that even opponents see anti-monopoly sentiment as the conventional wisdom. But from 1980-2016, the idea of taking on monopolies was considered fringe. Ronald Reagan’s antitrust chief Bill Baxter, whose great accomplishment was to begin the shutting down of antitrust in America, fought the U.S. Supreme Court’s “wacko” decisions maintaining monopolization standards, refused to enforce anti-merger laws, and dropped the major antitrust case against IBM, signaling to Wall Street and corporate America that it was time for a historic merger wave. And he did it with virtually no opposition. Even into much of the Obama Presidency, virtually no one gave a second thought to monopoly power. You will need a tremendous shift in the “norm” to change things.

But even if there is a change in “norm”, there will be a cat fight. While the subcommittee was led by Democrats, in particular Chairman David Cicilline, there is Republican support for addressing monopolies. Republican Ken Buck, a conservative from Colorado, released his own additional views to the report but suggested a much milder set of remedies. But the leader of Republicans on the committee, Jim Jordan, who also issued a major dissent from the report (with a document probably financed and written by antitrust lawyers working for Google, Amazon, and Facebook) wanted changes in telecommunications law – more enraged about whether posts get deleted on social media than he was about monopoly.

I shall hold my fire for a bit. A Google antitrust case is likely to be announced this week or next (and DOJ lawyers have been saying it is too early, that they are not sufficney proposed, it was accelerated due to political considerations. Who knew?). So let’s see how that rolls out.

Laws will always be years behind the society it ostensibly regulates. New technologies always have a way of making old laws seem obsolete. And that can set off a flurry of fumbling, half-hearted activity at every level, from cities and towns to states to the federal government, as lawmakers try to catch up and fill any gaps. Because at the end of the day, for all of these digital companies, the issue is the same: it’s all about human behavior. Any antitrust investigations should consider the aggregation of data, the predictability of behavior, and how Amazon-Facebook-Google (not Apple so much) can manipulate behavior.

What was not be on the House committee agenda were the deeper issues at stake here. To borrow from my monograph work-in-progress:

• Since the outbreak of COVID-19, governments have turned their attention to digital contact tracing. In many countries, public debate has focused on the risks this technology poses to privacy, with advocates and experts sounding alarm bells about surveillance and mission creep reminiscent of the post 9/11 era. Yet, when Apple and Google launched their contact tracing API in April 2020, some of the world’s leading privacy experts applauded this initiative for its privacy-preserving technical specifications. In an interesting twist, the tech giants came to be portrayed as greater champions of privacy than some democratic governments. We need to view developments like the Apple/Google API in terms of a broader phenomenon whereby tech corporations are encroaching into ever new spheres of social life. From this perspective, the (legitimate) advantage these actors have accrued in the sphere of the production of digital goods provides them with (illegitimate) access to the spheres of health and medicine, and more worrisome, to the sphere of politics. These sphere transgressions raise numerous risks that are not captured by the focus on privacy harms. Namely, a crowding out of essential spherical expertise, new dependencies on corporate actors for the delivery of essential, public goods, the shaping of (global) public policy by non-representative, private actors and ultimately, the accumulation of decision-making power across multiple spheres.

• In 2015, Benjamin Bratton published an influential book entitled The Stack which I have quoted in numerous posts. You need to read it in conjunction with Vincent Mosco’s The Digital Sublime, written in 2005. Both writers focus on a central proposition: that digital computing and the digital tech operational scheme will become/has become a global leviathan. Bratton writes that current computing systems are best conceptualised as a global megastructure —the Stack – that is layered by six tiers (Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface, and User) and that has rendered all current forms of governance and sovereignty obsolete. It has lead to the transformation of society but dictated by the constraints and control of the growing digital giants who have overturn all traditional economic, social and political relationships, and not to the consumer or citizen’s benefit.

In fairness, the committee has been clear that nothing will pass this year. For anything to pass at all, Democrats may have to take back the presidency and the Senate, and make it through what promises to be a chaotic and even dangerous transfer of power. Until and unless that happens, the status quo seems likely to endure.

And yet even in a world where many of these changes were to be adopted, how different would the tech world really become? If Amazon couldn’t use seller data to inform new product decisions, and Apple couldn’t take 30 percent of Spotify’s revenue, and Google couldn’t put its inferior restaurant reviews above Yelp’s, would Silicon Valley truly be rocked on its axis? The marketplace would certainly seem fairer. But I’m sure it would operate much differently day to day.

Brace yourself for a wild ride.