Prohibited (“blacklisted”) activities, stuff that automatically triggers regulatory scrutiny (“greylisted”), and maybe lots of opportunities to make some money if you do compliance work

5 October 2020 (Chania, Crete) – There’s an old joke that war is how God teaches Americans geography. Only this time around it’s tech regulation. It was brought to mind because of all sorts of issues with the ways that the U.S. government has addressed Tiktok in 2020. No, it really has nothing to do with Trump paying off Oracle cofounder Larry Ellison for his major backing of the Trump administration, one of the few Silicon Valley tech moguls to back Trump. Nor does it have anything to do with TikTok tanking that Trump rally.

It is much, much more fundamental and the U.S. acted as though this is a one-off, rather than understanding that this is the new normal – there will be hundreds more TikToks. Because we can no longer assume that the important tech companies and tech products themselves are American. This is the first time that Americans have really had to deal with their teenagers using a form of mass media that isn’t created in their country by people who mostly share their values. It’s from somewhere else. That’s compounded by the fact that the “somewhere else” is China, with all of the political and geopolitical issues that come with that. But I’d suggest that the core, structural issue is that it’s foreign. This is, of course, a problem that the rest of the world has been wrestling with since 1994, but it comes as something of a shock in Washington DC.

My God, how the world has changed. When Netscape launched in 1994 and kicked off the consumer internet, there were maybe 100m PCs on earth, and over half of them were in the U.S. (according to a McKinsey survey and analysis). The web was invented in Switzerland, and computers were invented in the UK … but the internet was American. American companies set the agenda and created most of the important products and services, and American attitudes, cultures and laws around regulation and speech dominated.

No longer. We can argue about the details of this all day (I have a very in-depth piece on TikTok in progress which articulates the many points). But what seems clear is we should just presume a global diffusion of software creation and internet company creation. It doesn’t really matter if Silicon Valley ends up as 25% or 75% of the next 100 important companies – America doesn’t have a monopoly on the agenda any more.

The EU has had to deal with this for ages. It’s thus well ahead in knowing how to deal with it: through regulation and “more sensible” antitrust laws based around encouraging competition, although even in EU much is lacking. But the EU “gets it” in one important matter: you simple cannot “one-at-a-time” this stuff. You need a systematic, repeatable approach. You can’t ask to know the citizenship of the shareholders in every popular app – you need rules that apply to everyone.

Today, the rules come from Apple, or California, both of which are increasingly becoming America’s privacy regulators by default. But they will also come from the EU, which is increasingly writing laws that, intentionally or not, change how American companies do business in America, and the more different rules we have in different places, the more fragmented and complicated things get. Regulation is an export industry, and a competitive industry. Some regulators are finally getting that.

The EU utterly failed to foster the growth of home grown tech competitors, and I have articulated the reasons many times before. The power of Silicon Valley and the U.S. government, and the matching power of Beijing, is born of deep reserves of attitude, capital, talent and research capabilities that the EU could never match. Which is a shame because France and Germany still have some of the best mathematicians and engineers in the world. Technology was a big topic at the Munich Security Conference this year (my media team’s last event before the COVID-19 onslaught) and the “post-Westphalian digital world”. But the nature of the topic had fundamentally changed from just two years ago when the debate was about actual technology: AI, Sophia the Robot, 5G, the IoT, and autonomous weapon systems. This year it was not about the technology itself but “who will control the tech?” Judging from the composition of panels at Munich, it wasn’t going to be the EU. Over the course of the Munich event, the narrative was formed (or rather cemented) that the battle over tech will be fought by just two actors: the United States and China. No room for other players. No room for the EU.

Hence, with the EU’s absence in any element of the digital age’s data architecture, it had to carve out a niche for itself. The EU chose to prioritize data protection over technology investment. For 15 years the EU has served as the world’s leading digital police force, making up for its lack of massive tech companies by wielding tools such as multibillion-dollar antitrust fines, tax claw-backs and laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (which is failing but that’s another issue).

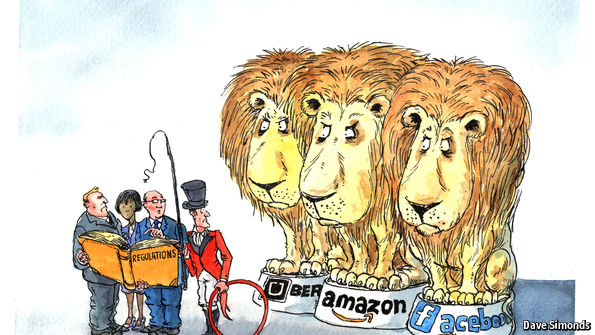

And it has not been easy. The EU Commission has been perplexed why Big Tech behavior “has not changed with these fines and all this EU action” – the thought recently expressed by Margrethe Vestager in an unguarded moment. She has dual roles: the EU’s Competition Commissioner, and also as Commission Executive Vice-President for dealing with Europe and the Digital Age.

So there has been a gear shift in EU digital policymaking in which lawmakers felt they needed a “redo” and a rethink. Because they saw the opportunity to export their regulation to the rest of the world (excluding China) if done right – tougher privacy standards, better competition rulings and calls for tighter policing of online content. The point was to establish Brussels as a global first-mover on tech regulation, an area where Washington D.C. largely stood still. But there were and are tectonic issues. Because when you trade data, geographic proximity becomes irrelevant. Regulation becomes an algorithm. The idea of the EU as the global regulator depends on technology not advancing (see more below).

So last week we get a “leaked” document from the European Commission after all this “redoing and rethinking” which considers a wide range of regulations for tech giants which features “blacklisted” or “greylisted” actions. I think it was a deliberate leak so that the Commission could send out some trial balloons and get feedback. You can read the whole document by clicking here.

It’s certainly far wider than any U.S. legislative bill or proposal currently being contemplated. As I have noted in other analysis I have done on tech regulation, that’s probably down to the fact that the targeted companies are based in the U.S. which have a better-developed lobbying capacity there, and have successfully convinced U.S. politicos of the (largely true) proposition that they are a means of projecting U.S. soft power abroad.

It’s a long read and worth your time but herein a few of the big points. Prohibited (“blacklisted”) activities include:

* Mining your customers’ data to compete with them or advertise to their customers (think: Facebook Like buttons on publisher pages, Amazon’s own-brand competitors)

* Mixing third-party data with surveillance data you gather yourself (like Facebook buying credit bureau data), without user permission (which is the same as never because no one in the world wants this)

* Ranking your own offerings above your competitors (think: Google Shopping listings at the top of search results)

* Pre-installing your own apps on devices (like iOS and Android do) or requiring third party device makers to install your apps (as Android does)

And for my legal technology law firm/vendor readers, the potential to make lots of money if any of this stuff gets enacted. Companies have to provide:

* Annual transparency reports that make public the results of an EU-designed audit that assesses compliance

* Annual algorithmic transparency reports that disclose a third-party audit of “customer profiling” and “cross-service tracking”

* Compliance documents showing current practices, on demand by regulators

* Advance notice of all mergers and acquisitions

* An internal compliance officer who oversees the business

Those are the requirements. There’s a long list of “greylist” stuff that isn’t banned or mandated, but that automatically triggers regulatory scrutiny. It is one hell of a list and I urge you to read the whole thing. A few of them:

* Interfering with the businesses on a platform from getting their own data (eg Amazon refusing to tell publishers how their books are selling)

* Gathering more data than is needed to provide the service

* Making it hard for users or businesses on a platform to export their data and go elsewhere

* Encumbering the sale of click/search data or offering it on discriminatory tools that preference some customers over others

* Using DRM or ToS to stop vendors from replacing the default apps on devices

* Blocking third-party mobile apps from using the APIs and API features that the vendor’s own apps use

* Blocking identity services that offer “the same level of security” as your own

* Degrading service for third-party apps, locking users into your own payment or insurance services, locking users into your identity services

* Price-discrimination among businesses that use platforms (“most favored nation” deals, etc)

* ToS that “require acceptance of supplementary conditions or services that, by their nature or according to commercial usage have no connection with and are not necessary for the provision of the platform or services to its business users.”

My immediate reaction: all of these rules sound good, but they will be very, very hard to enforce, and 90% of them could be scrapped if you just had a different rule: “structural separation.” Yes, the old, tried-and-true anti-monopoly rule that bans platforms from competing with the businesses that use their platforms, like rail companies were banned from owning freight companies.

A structural separation rule for Big Tech would ban Facebook and Google from running their own ad networks; or Apple and Google from making apps that ran on their mobile platforms; or Amazon from publishing books or selling own-brand goods.

Is “structural separation” possible? Who knows. But it has been talked about for a few years and it is certainly the reason Facebook put out its “treatise” last week on why Facebook is “too complex to be broken up”. I will address many of these points in a draft monograph I will distribute in about one week for your comment, a look at the regulatory state in the Information Age, in the era of informational capitalism. But just some concluding points on the EU’s proposed rules:

* how do you define “Big Tech” for the ban?

* what do you do when/if Facebook folds?

* What counts as “your data”?

* Can emails be rescinded?

* How do you handle collaborative or archival efforts?

* And what about stuff like abandonware? How is it audited and enforced?

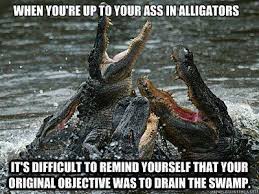

Yes, yes. Lot of this stuff is imminently sensible. But let’s think it through. Because, to me, one big point is that this level of regulation adds enormous financial burdens to upstart competitors and simply entrenches dominant players. And that’s what the EU does not want, correct? It’s what the GDPR has done, strengthen the dominant players. Pity to repeat that. As the saying goes:

Digital is different from earlier general-purpose technologies in a number of significant ways. It has zero marginal costs, which means that once you have made the investment to create something it costs almost nothing to replicate it a billion times. It is subject to very powerful network effects – which mean that if your product becomes sufficiently popular then it becomes, effectively, impregnable. The original design axioms of the internet – no central ownership or control, and indifference to what it was used for so long as users conformed to its technical protocols – created an environment for what became known as “permissionless innovation”. And because every networked device had to be identified and logged, it was also a giant surveillance machine. As the security guru Bruce Schneier says all the time: “Surveillance is the business model of the internet. That is going to be very tough to undo.”

But because providing those services involved expense – on servers, bandwidth, tech support, etc – people had to pay for them. It may seem incredible now, but once upon a time having an email account cost money. Then newspaper and magazine publishers began putting content on to web servers that could be freely accessed, and in 1996 Hotmail was launched (symbolically, on 4 July, Independence Day) and then … well, you know the history.

All government regulators/enforcers (privacy, anti-trust) at least in the West are facing an almost losing battle. Under the rubric of “ubiquitous computing,” “smart dust,” and the “Internet of Things,” computers are melting into the fabric of everyday life. Light bulbs, toasters, even toothbrushes are being chipped. You can summon Alexa almost anywhere. And as life becomes computerized, computers become lifelike. Modern hardware and software have gotten so complicated that they resemble the organic: messy, unpredictable, inscrutable. In machine learning, engineer after engineer forswears any detailed understanding of what goes on inside.

I’ll leave it there for the moment. The EU proposals will be dissected by Big Tech and many regulators. But in closing, I think in this digital age many struggle (delusionally) to defend liberal values and concepts of competition and “fairness” that we developed in an analogue era, and they do not understand the complexity we have created. By introducing technology so very rapidly into every aspect of the human existence in such a preposterously short historical period of time, Big Tech has thrown “a metaphorical person into all our lives” as Julia Hobsbawm terms it.

When that type of technology is introduced into society, unimpeded, through private enterprise, and then quickly adapted and adopted, you’ve built a world, a system, in which physical and social technologies co-evolve in complexity. It will bedevil the regulatory state.