The internet has been quietly “rewired”, and video is the reason.

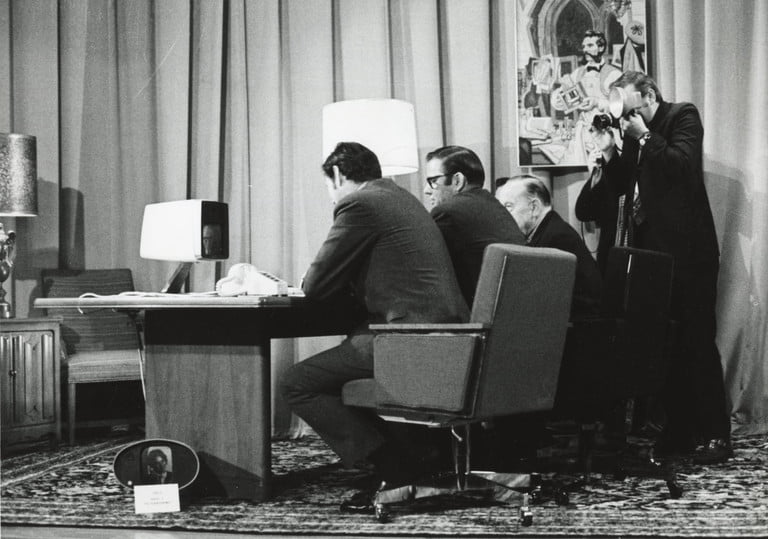

Pittsburgh Mayor Peter Flaherty at the first public demonstration of the Picturephone on 30 June 1970

15 July 2020 (Chania, Crete) – Last month my media team was reporting back to me on what they had found when examining the coronavirus lock-downs and related disruptions vis-a-vis what this was all doing both affecting technology and effecting technology (a wide range, across many subject areas). The patterns were familiar. We always start by making the “new” tech fit the existing ways that we work. We are taking post-COVID “new new” things and applying them to the “old old” ways we used to work and live. I’ll expand on that point in greater detail in a longer post (which even includes a quote from Henry Kissinger!) but for this post let’s look just at video.

The photo above was shot 50 years ago. It shows Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Mayor Pete Flaherty (the guy on the left) staring at the tiny face of John Harper, chairman of Alcoa Corporation, on a small, low-resolution, black-and-white display. The occasion was the first public demonstration of Bell Labs and AT&T’s Picturephone system, held in a chintzy living room set in the Bell Telephone HQ auditorium in Pittsburgh. At the time, Alcoa was the third largest aluminium producer in the world, headquartered in Pittsburgh, and AT&T’s first corporate customer for the Picturephone system.

Long before Zoom, Skype, FaceTime, and Google Hangouts were a daily reality, this highly publicized event was supposed to signal the start of a network of two-way videophones that would stretch across first Pittsburgh, then the United States, and eventually the world. The video call was the technology that was always on the cusp of widespread adoption, but never quite got there. It was futuristic technology that always appeared to be just around the corner.

The 1970 formal announcement, and the broadcast of the first call:

AT&T’s Picturephone was, in essence, a combination telephone and TV set. AT&T, which spent an estimated $500 million on the endeavor, predicted that, by 1975, there would be 50,000 such Picturephones in 25 cities around America. In the 1970 press release AT&T predicted that 1 million units would be sold.

Things didn’t exactly roll-out like that. Commercially speaking, the Picturephone was a flop. It was too expensive, costing a monthly fee of almost $1,000 in today’s terms for access to the technology, and an additional charge per minute of use. Customers worried about how they would appear on the screen of the other user, there being no vanity picture-in-picture window for them to see themselves during the call. It was also unwieldy. In order to work, the Picturephone tied up multiple phone lines simultaneously to get sufficient bandwidth to transmit the necessary audio and video analog signals. By 1972, only a handful of sets had been sold in Pittsburgh. When AT&T switched CEOs in 1973, the writing was on the wall, and the project was brutally canceled.

Side note: several of the original Picturephones have been modified for current video-calling software:

The Picturephone was really ahead of its time. Last year I was at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, which holds two of the surviving Picturephones in its university archives. Chris Harrison, an Associate Professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute (part of the University) whom I had met that year at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona was giving a presentation on the future of video. He told us:

Having opened up these AT&T machines to take photos of the interior, I can tell you it was absolutely jam-packed with cutting-edge technology … for 1970 … and the industrial design was just incredible. It was a beautiful machine. It must have been so futuristic at that moment. It looked like something right out of “The Jetsons”.

But as Harrison noted, one of the big details of the AT&T Picturephone desktop was the sharing feature, noted in the video of the call above, but not heavily discussed or picked up by many analysts. It allowed users to share their literal desktops, way before graphical user interfaces gave us metaphorical desktops to work on.

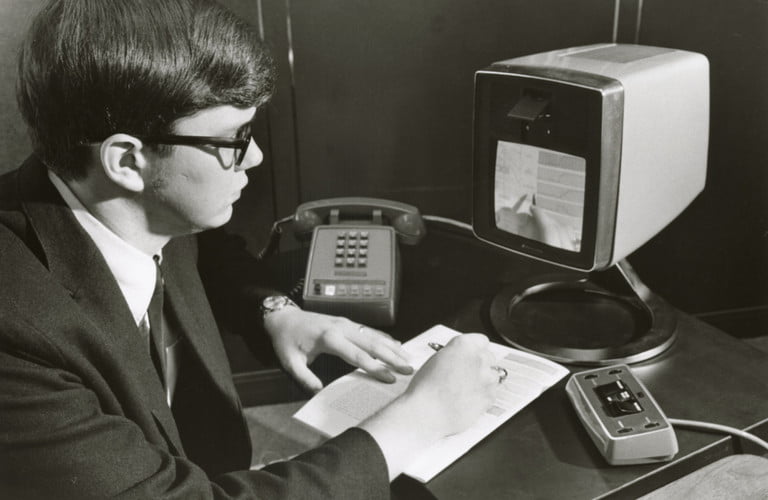

Richard Gilman, a Bell Lab engineer, demonstrates how graphic information or computer data can be transmitted via Picturephone (30 June 1970)

By flipping a small mirror over the device’s camera, you could show the person on the other end of the two-way conversation an object on your desk. You could have a piece of paper in the view and write on it, and the other person would see that in real time. As Harrison noted, the developers were really thinking this through as a business tool.

For the longest time, it seemed video calling would remain the ultimate science fiction dream. AT&T’s failure with the Picturephone seemed to hammer this point home. Had the concept not seemed so exciting to tech geeks, it doubtless would have died right there in the decade of disco and Watergate. But many tech developers picked up on the business tool side of the Picturephone and began tweaking and tinkering.

NOTE: many of those tech developers were at the legendary Silicon Valley research laboratory called Xerox PARC (an abbreviation for Palo Alto Research Center) which is also celebrating its 50th birthday this year. PARC became the inventor and incubator of many elements of modern computing in the contemporary office work place: laser printers; computer-generated bitmap graphics; graphical user interface, featuring skeuomorphic windows and icons, operated with a mouse; Ethernet networks; and the first computer operating system that could support video display.

And it’s important to note the Picturephone was not, in fact, the first time researchers had tried to make video calling a reality. Virtually since the moment that Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876, there was exploration into a similar calling system built around images as well as voice. The French science fiction writer Louis Figuier claimed that Bell was working on something called a “telephonoscope” combining real-time sound and image. An 1879 cartoon by George du Maurier, which appeared in the Punch Almanack, jokingly depicted a similar device, supposedly created by the American inventor Thomas Edison. Trading cards produced under the name “In the year 2000″ sold as souvenirs at the 1900 Paris Exposition, imagined “Correspondance Cinema-Phono-Telegraphique.”

The idea, for the same reason that it tantalized engineers, cropped up in works of fiction. A 1889 story by Jules Verne titled In the year 2889 describes how people of the future communicate via a “telephote.” He wrote:

“Oh, the telephote, the wires of which Legrand uses to communicate with his Paris mansion. Here is another of the great triumphs of science in our time. But the transmission of speech is an old story; soon there shall be the transmission of images by means of sensitive mirrors connected by wires – such will be a thing!”

The first screen appearance of video calling may well be Fritz Lang’s 1927 science fiction masterpiece Metropolis:

Although it was far from the last time that it was depicted on screen. Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 epic 2001: A Space Odyssey is probably the most notable example:

There were various prototypes as well, although they lacked the underlying infrastructure of the 1970 Picturephone call. A Bell Labs prototype was shown off at the 1964 World’s Fair, along with future wonders including IBM’s System/360 series of computer mainframes, handwriting recognition technology, machine translation, and architects’ models of the forthcoming Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Soon after, Bell Labs created public prototype Picturephone booths in New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. These allowed people to make three-minute calls across the U.S. for a whopping $27. For whatever reason, payphones costing the modern equivalent of $223 for 180 seconds of conversation never took off.

Even after the failure of the 1970s Picturephone, AT&T didn’t entirely give up on the idea of a commercial line of video calling devices. In 1992, it tried again with the full color, 10fps Videophone 2500. This time, both video and audio were transmitted along one telephone line, although this compression resulted in poor quality picture and sound. The following year, it slashed $500 off the $1,499 price, and threw in the towel (again) by 1995.

And today?

Given our current reliance on video calling, this history of failure might seem surprising. As recently as the early 2000s, it still wasn’t clear that video calls would ever become a mainstream proposition. A 2004 paper, published in the journal Technological Forecasting and Social Change, was titled “On the persistence of lackluster demand — the history of the video telephone.” It offered up the videophone as a case study in technology that repeatedly failed to catch on. Some lessons derived by the authors include “not every new technology leads to stunning market success; just because the press says it will, does not mean it will. Technological convergence is not a certainty.”

Today, of course, we know different. Just a couple of years after that paper was published, Skype video calling launched on Windows. Before long, every desktop computer and laptop shipped with a built-in webcam. Then came smartphones and tablets with front-facing cameras, ubiquitous broadband, and the advent of services like FaceTime, Google Hangouts, and Zoom.

While the core dream remains the same as it was in the 1970s (and, for that matter, in the 1870s), the technology has continued to iterate. For example, Apple’s iOS 13 uses AR trickery to “correct” the eyeline on FaceTime calls, meaning that users no longer need to choose between looking at the person (and appearing to be staring off-screen) or at their camera (and appearing to look at the other person, but not actually be looking at them on the screen). Apple is also working on an even better tweak: improving the lighting on the person you are calling. Many times on Zoom chats or video interviews the host/interviewer always has better lighting because she/he has better equipment. Apple wants to compensate for that through AR to “correct” everybody’s lighting. Tweaks like this, minor as they might be, will help make video calls even more immersive and make it more like you’re having an everyday chat with a person.

And yet, irony of ironies, video calling has perhaps become so normalized that we no longer think of it as particularly special. We’re in this moment now where the window in which this was a spectacular, futuristic technology quickly compressed into a kind of mundane ubiquity. Now it’s just another utility. It’s an essential action that is routine, so it’s lost some of that aura of grandeur.

A few year’s ago Google’s then-Chairman, Eric Schmidt, caused a few heads to explode at the World Economic Forum at Davos when he said that the internet will disappear. He was totally misinterpreted. No, our vital supply of cat pictures and men jumping over barbecue pits were not going to disappear. Rather, he was making a useful point about the economics of technologies as they mature. They become so built into our societies and lives that we stop really noticing that they are there. For example, we all use artificial light but it’s really only a century ago that it became something that was common. And it’s much more recent than that it actually became affordable to the point that we simply don’t worry about using it. The light bulb was a noticeable technology until really quite recently. Now we really only note its absence.

This same progression will happen with video.

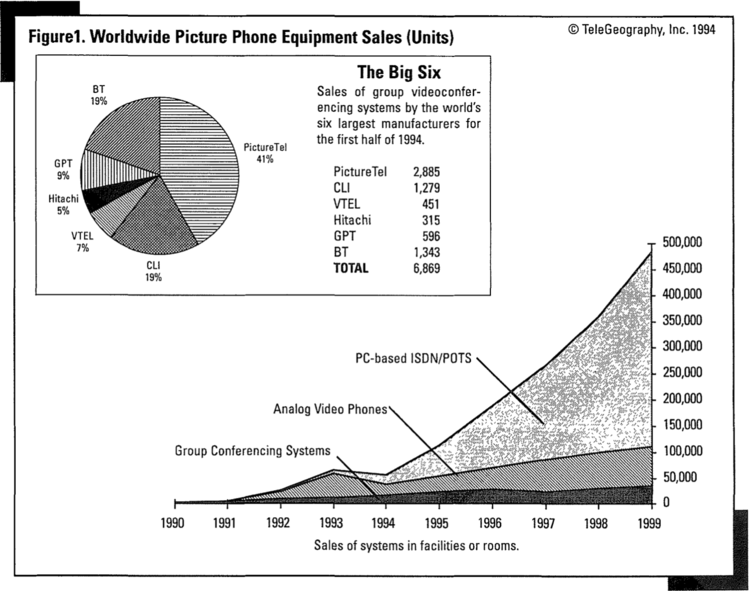

As I continued to track the history of picture phones and video phones and video calls from that 1970 event, I came into the video conferencing “epoch” in the 1990s, just as the web was taking off. It was very expensive, an impractical tool for many companies. Many of my mobile technology readers will remember that it became a big use case for 3G, which didn’t happen at all. With the growth of consumer broadband we got all sorts of tools that could do it, but it never really became a mass-market consumer behavior.

Now, suddenly, we’re all locked down. We’re all on video calls … ad naueum. All the time. Team stand-ups. Play dates. Family birthday parties. Catch-up time. Sometimes in bereavement with loved ones in a hospital or hospice. Suddenly Zoom is a big deal. At some point many of those meetings will turn back into coffees, we hope, but video will remain. Will it still be Zoom, though? As a breakthrough product, it’s useful to compare Zoom with two previous products – Dropbox and Skype.

Part of the founding legend of Dropbox … a story repeated and repeated in just about every media piece on the company … is that Drew Houston (the company’s co-founder) told people what he wanted to do, and everyone said “there are hundreds of these products already” and he replied “yes, but which one do you actually use?” And, bang. That’s what Zoom did. Video calls were nothing new. But what Zoom solved were all those small pieces of friction that made it fiddly to get into a call.

Now, the other comparison. Skype. Just like video, Voice-over-Internet-Protocol (VOIP) was around for a long time, but Skype solved a lot of pieces of friction, in both engineering and user experience, and by doing so made VOIP a consumer product. But two things happened to Skype after that, and that changed the expected paradigm. As Benedict Evans has noted in his history of Skype:

The first is that the product drifted for a long time, and the quality of the user experience declined.

But the second is that everything had voice or was getting voice. Imagine trying to do a market map today of which apps on a smartphone, Mac or PC, IoT device might have voice – it would be absurd. Everything can have voice. And though there’s still a lot of engineering under the hood, it has become a commodity. What matters now is only how you wrap it. If you’d looked at Skype in 2004 and argued that it would “own” voice on computers, while all of this voice development was going on, you’d have completely missed the business model.

In my estimation, this is where we’ll go with video. Yes, there will continue to be hard engineering, but video itself will be a commodity and the question will only be how you wrap it. There will be video in everything, just as there is voice in everything, and there will be a great deal of proliferation into industry verticals on one hand and into unbundling pieces of the tech stack on the other. Interesting companies will be created, and on the other hand established players … for instance, Slack is deploying video on top of Amazon’s building blocks … will create their own bundling and unbundling. Everything will be “video”. It will disappear inside.

Look at what Apple and Google are doing, albeit in separate ventures. Zoom blew them out of their chairs. But they realized they have the advantage of network effects. So they decided “let’s change the paradigm”. In the future, you won’t necessarily need an account to join a video call, and you generally won’t need an application either, especially on the desktop. It will be built right in. You’ll just click on a link in your calendar and the video call opens in the browser. Indeed, the calendar becomes the aggregation layer – you don’t need to know what service the call uses, just when it is. And with the AR trickery I noted above to correct the visuals, users will no longer need to choose between looking at the person (and appearing to be staring off-screen) or at their camera, or worry about proper lighting, etc. So video taping will be child’s play.

NOTE: the next version of the iPhone and it’s new iOS will bring this in even sharper focus. The phone will have four cameras on back, one in front. New software will allow simultaneous filming with both front and back cameras. From a commercial standpoint, it’s marvellous When my media crew covers a conference, or does on-the-street/impromptu interviews, they will be able to conduct the interviews so that both the interviewer asking the questions, and the interviewee, will be filmed. A few simple edits with any of the high-end mobile video editing apps and … voila! Send it out on Facebook, Twitter and/or upload to Youtube. More details on how all that will work in an upcoming post.

Incidentally, one of the ways this stuff feels very “1.0” is the rather artificial distinction between calls that are based on a “room”, where the addressing system is a URL and anyone can join without an account, and calls that are based on “people”, where everyone joining needs their own address, whether it’s a phone number, an account or something else. Hence now you see Google has both Meet (URLs) and Duo (people) while Apple’s FaceTime is only people (no URLs). That will all merge as time goes by.

Taking this one step further, a big part of the friction that Zoom removed was that you don’t need an account, an app or a social graph to use it: Zoom made network effects irrelevant. But, that means Zoom doesn’t have those network effects either. It grew by removing defenses. It is going to face some keen competition.

In addition to the Zoom comparisons with Dropbox and Skype, here is yet another useful comparison: photo sharing. There have always been hundreds of vendors that did this, but we saw a succession of companies that worked out something new around user experience and psychology that took them beyond “photos” to some deeper insight – first Flickr, then Facebook and Instagram … and then Snap. Why is Snap relevant to this conversation? Progression:

• When Snap launched, there were infinite way to share images, but Snap asked a bunch of weird questions that no-one had really asked before: “Why do you have to press the camera button? Why doesn’t the app open in the camera? Why are you saving your messages? Isn’t that like saving all your phone calls?”

• Fundamentally, Snap asked “why, exactly, are you sending a picture? What is the underlying social purpose?’ You’re not really sending someone a sheet of pixels – you’re communicating. Get it?”

That’s the question Zoom and all its competitors have not really asked. Zoom has done a good job of asking why it was hard to get into a call, but hasn’t really asked why we’re doing this call in this way in the first place, and not developing it better. Why am I looking at a grid of little thumbnails of faces when I have the tech for alternate zoom-in? What is the “mute” button for – for me to enjoy background noise, or so I can talk to someone else, or is it so I can turn it off to raise my hand? What is screen-sharing for? What other questions could one ask? So we are kind of waiting for the Snap version of video. This is how mobile tech has always progressed.

But we need to understand the power and opportunity of video, beyond the development of video phones and video calls. Long-form and short-form video is now the most popular content format regardless of screen size, according to the latest “Video Index” from Ooyala, a company that has been at the forefront of understanding the ecosystem of online video platforms. I have used their video analytics and monetization solutions for years. They are among the best in the business. Video currently accounts for 70% of all internet traffic. Video dominates rich media tactics for online and direct marketing professionals, becoming the virtual “calling card” for marketing companies across all industries.

Because if you are a business, consumers will like it if it’s easy to digest, entertaining and engaging. It can capture an identity, and show personality. Video can humanize a brand and establish a connection with the viewer. While you could publish a blog post or share photos on social media, there is nothing more personal than video. Video content allows your customers to see inside your operation, get a feel for your personality. According to the Digital Marketing Institute (DMI), the primary reason video is so popular these days is that it’s an easy-to-digest format that gives our eyes a rest from the overabundance of textual information online. And the DMI also advises “do not do it all yourself”. Independent “explainers” can help educate people about your product and can be used in conjunction with instructions, customer service activities, and a whole other range of applications. Interviews can help showcase a special member of your team, or influencer.

I got involved in video in 2010 when Larry Center (a long-time friend and the now-retired Dean of the Georgetown University Law Department of Continuing Legal Education) invited me to Washington, DC to interview panelists and attendees at Georgetown Law’s first mega “Future of the Law” event. My first interview was with Richard Susskind:

The production quality was primitive, and I was not prepared. I was still learning the process. But what hit me in this 2010 interview were his comments on video conferencing and how high-quality video technology would transform the legal industry.

The very next month I was off to London to cover the launch of Georgetown Law’s “Corporate Counsel Institute-Europe”, and Georgetown could not have done better than land me the keynote speaker, Mario Monti, who would become Italy’s Prime Minister in one year’s time:

Still a little primitive but production quality was way up – more expensive cameras, a graphic artist to add some intro flourishes, etc.

And my timing was perfect. Ben Thompson (best known now for his weekly column “Stratechery”) was one of Apple’s key strategy and marketing thinkers and he had just published a piece on how the internet will be quietly “rewired”, and video will be the reason. A big reason why that would happen was due to the rapid expansion in a special kind of infrastructure that gets viewers their video interruption-free (not so seamless in 2010; remember buffering?). We would see the development of content delivery networks (CDNs in the business), private networks owned by the world’s biggest tech companies like Apple, Facebook, and Google. Netflix would become a serious CDN, but that would be later.

And that is exactly what happened, with a handful of firms that specialize in content delivery, operations that run in parallel to the internet’s core traffic routes. The shift has been so pronounced that well over half of all traffic flowing over the internet today actually traverses these parallel routes, according to data from research firm TeleGeography.

It was a fundamental change to the way data had been routed over the internet, which was classically conceived of as a tiered hierarchy of internet providers, with about a dozen large networks comprising the “backbone” of the internet. The internet today is no longer tiered; instead, the experts who measure the global network have a new description for what’s going on: it’s flattened the internet. It happened even without people noticing.

And without getting too far into the weeds, it was the internet’s new, flattened structure that meant content owners like Google and Netflix have more power than ever to control how their content reaches the end-consumer. That rewired internet has led to an intensifying struggle between the web’s biggest companies and the legacy carriers who own the pipes; greater pressure on small access providers to get streams to their rural customers; and made it harder for content companies to compete without their own privileged CDN pathways. Ultimately, consumers could cede more choice to a small number of companies who own both the content on the internet and the means to deliver it. That is the tech battle today. Even the staunchest digital-rights defenders aren’t quite sure what to make of the consolidation of power in a flattened internet.

And there are many other nuances … such as algorithmic preferences … to the flat-internet phenomenon. As video flows through increasingly vertically integrated networks, technologies that hew to the net’s principles of decentralization are getting left behind. It’s a simple function of supply and demand – video piped directly from Amazon or Netflix to a consumer ISP is simply a better experience. Lots more I could say but let’s move on.

The Internet has changed the movie business drastically as well, not only by affecting how movies are marketed and watched, but also by changing the pathways and entrances to the movie industry itself.

And that directly affects me as I have moved from video to film production. Today, there is still a lot of networking and dues-paying to get into the movie business, but the Internet has radically changed what that looks like; and the biggest change has been in accessibility. Combined with the advent of cheap digital technology, the Internet now makes it much easier for almost anyone to do a video or film project and get it seen. Web sites like YouTube and Vimeo have made it so anyone with a camera can post a video, and computers now have editing capabilities to help anyone “tweak” their projects and make them look better. As a result, millions of aspiring filmmakers, who otherwise would not have the resources to get seen, can now “go public” on their own.

You still have to be good to stand out, especially with all the competition on the web. I’m doing fine. I’ve assembled a 12-person media team that includes writers, researchers, graphic artists and camera experts, and I’m about to finish my first two film projects. But I’ll let you be the judge. You can see some of my video and film work by clicking here.

I’ll close out this post with this:

When I was doing war crimes investigation work for the International Criminal Court I worked with several incredible tech geeks who could take mobile phones and laptops and pull off incredible evidence. I became fascinated by “photogrammetry” which is the science and technology of obtaining reliable information about physical objects and the environment through the process of recording, measuring and interpreting photographic images and patterns of electromagnetic radiant imagery and other phenomena. Besides war crimes work, photogrammetry is used in many fields such as topographic mapping, and archaeologists use it to produce plans of large or complex sites, which I learned in my many sojourns across Crete visiting antiquity sites.

Variations of photogrammetry are also in the core computer graphics technology used in digital film production. It led me to the visual effects editor Ian Hubert who gives lessons on Youtube and who has been developing downmarket versions of the (massively expensive) virtual reality and computer-generated imagery (CGI) enterprise software used by film studios. The Internet does provide much more access than before, to forward-thinking individuals with more innovative ways to use the web for filmmaking, and how to access the outstanding technology out there.

The video you are going to see below is a “downmarket version” of that enterprise software I noted above. And it shows you the power of the green screen. For those of you receive my digital media column, the following is primarily a mix of Microsoft Kinect and Blender. This is a film clip of Ian’s set-up, not mine, but I have duplicated it in Rome where I have built a small film studio to his exact specifications:

I am fascinated by the amount of imagination, creativity, and detail in projects like this but which normally have huge budgets. The enterprise-level software for what you see above is about €850,000 but we’ve been able to do a set-up with a downmarket version for about €25,000. Yes, it means no automatic settings or automatic sensor tracking/adjustment so it requires a lot of manual twiddling: best export/import settings, design, colors, values, lighting, scanning, getting people to track in the right places, etc., etc. And if you look closely you’ll see uneven lighting, blurred images, smoke, etc.

But as you watch it, and think “her movements look so casual” know they had to be meticulously planned and executed. It takes time. And note how the actress in this scene is bringing nothing. Because she has nothing to work with. Nothing to surprise her, nothing to catch her off guard. All she sees is the studio, the green screen so there’s nothing to even do, to touch. Although, to her credit, the way she turned to emulate the camera turning around her was amazing. Acting is actually using the scenery and other actors to bring life to a scene. So in these CGI situations you are giving the actors absolutely nothing to work with, often going as far as interacting with characters who are not even present and will be edited in later.

And a short note: the reason why the screen is green is because human skin has no green to it, so you can tell the computer “remove everything green on this square” and it won’t mess up the actor’s skin. If it were red or yellow it would be more difficult for the computer to differentiate skin from background because skin has some red and yellow in its color. In some cases a blue screen is preferable due to certain illumination or the need to use a green object.

Another reason is that most cameras typically have a Bayer filter, where their color sensors copy our eyes, which see green more than other colors. So a recording will have more green accuracy than other colors.

And how powerful is a green screen? Most of you will remember Baz Luhrmann’s version of The Great Gatsby with Leonardo Di Caprio from 2013. Almost everything in that movie was shot with a green screen. The actors had to imagine everything. There is a wonderful 1-1/2 hour documentary explaining the special effects (heavy on the tech explanation) but it’s not available on-line. However this short clip off Youtube will give you the general idea:

Yes, as we all know, the Internet has changed our world. Nearly every aspect of our society has been affected by it and has had to adapt. If telephones and airplanes made the world smaller, the Internet shrank it many times more. The ability to communicate instantly with anyone in the world – with words, pictures, music and video – has forced us to change how we do business, how we interact with the world around us, how we can be creative.

Ben Thompson had it right. The internet has been quietly “rewired”, and video is the reason. The power of video is its ability to tell a story in a way no other type of content can. This medium can really illuminate.