12 June 2020 (Chania, Crete) – The Egyptian pharaohs Hatshepsut and Akhenaten. The Roman emperors Nero, Domitian, Gallienus, Aurelian, Probus, Geta and Macrinus. Dictators like Napoleon Bonaparte, Francisco Franco, Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Lenin, François Duvalier and Saddam Hussein. History has seen a great many leaders toppled from their plinths. Christians systematically destroyed idols and statues representing pagan gods, as they saw them as representing savagery. At its best, expunging the past is a recognition by a society that it is hoping to finish one cycle and enter another, more enlightened, one. Symbolic lynchings, it would seem, are still necessary to move from one epoch to another.

It’s a tradition we seem to have rediscovered in recent weeks, as demonstrators across the world have made new additions to the list of victims of what the ancient Romans called Damnatio Memoriae – the damnation of memory. Damnatio Memoriae was the punishment applied to political figures who were condemned post mortem by the senate. Their statues were knocked over. Coins bearing their visage were melted. Their names were erased from the public space. Records of their lives and deeds were destroyed. Even poets and historians were prevented from naming them or refer to them in any way.

Toppling statues is undeniably a violent act, an assault on a realistic and symbolic replica of a person. Toppling a statue has always meant a break from old beliefs. Damnatio Memoriae was intended to enable a society to rid itself of its past, to obliterate whatever was found to be objectionable – or too painful to consider.

So having just re-read some William Faulkner material by Carl Rollyson (more on Faulkner below), I was intrigued by events after a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Bristol, England last weekend which saw protesters topple the statue of Edward Colston – the English merchant, philanthropist and slave trader – before dragging and rolling the bronze monument into the harbor.

The plaque on the pedestal for the statue.

What was interesting in the news reports was that during the toppling and sinking in Bristol, the police were told to stand back, the city fathers deciding to let them get on with it to “avoid tension”. Bristol mayor Marvin Rees looked sympathetically towards the act, stopping short only “as an elected official” of condoning law-breaking.

NOTE: earlier this week the statue was retrieved from the harbor. Watching the statue break the surface of the water, I was reminded of the practice of throwing penny coins into wells and fountains when I was a small child. A (much younger) UK mate told me that until 1992, the penny was made of bronze, so his early wishes were made of the same stuff as Colston’s effigy. The practice of throwing coins into wells is an ancient tradition, and may have emerged because copper (a component of bronze) has oligodynamic properties: it kills bacteria, making water safer to drink. It’s a shame they dredged it up: all that bronze at the bottom of the harbour might have made Bristol’s waters a little cleaner.

Colston (which everybody seems to know by now) was the deputy governor of the Royal Africa Company from 1680 to 1692, at that time Britain’s only official slaving company. For many, the sight of his statue dropping to the bottom of the River Avon, at the exact spot his ships would have once left for West Africa, was a fitting end to more than a century of his presence in the city centre. Throughout that time he was responsible for the transportation of some 84,500 enslaved men, women and children. Almost 20,000 of them did not survive the journey, and were thrown overboard. Of course, none of that was noted on the plaque above.

The statue was one of a number of landmarks in Bristol to take Colston’s name, although the nearby music venue Colston Hall will be renamed this year as part of a major refurbishment.

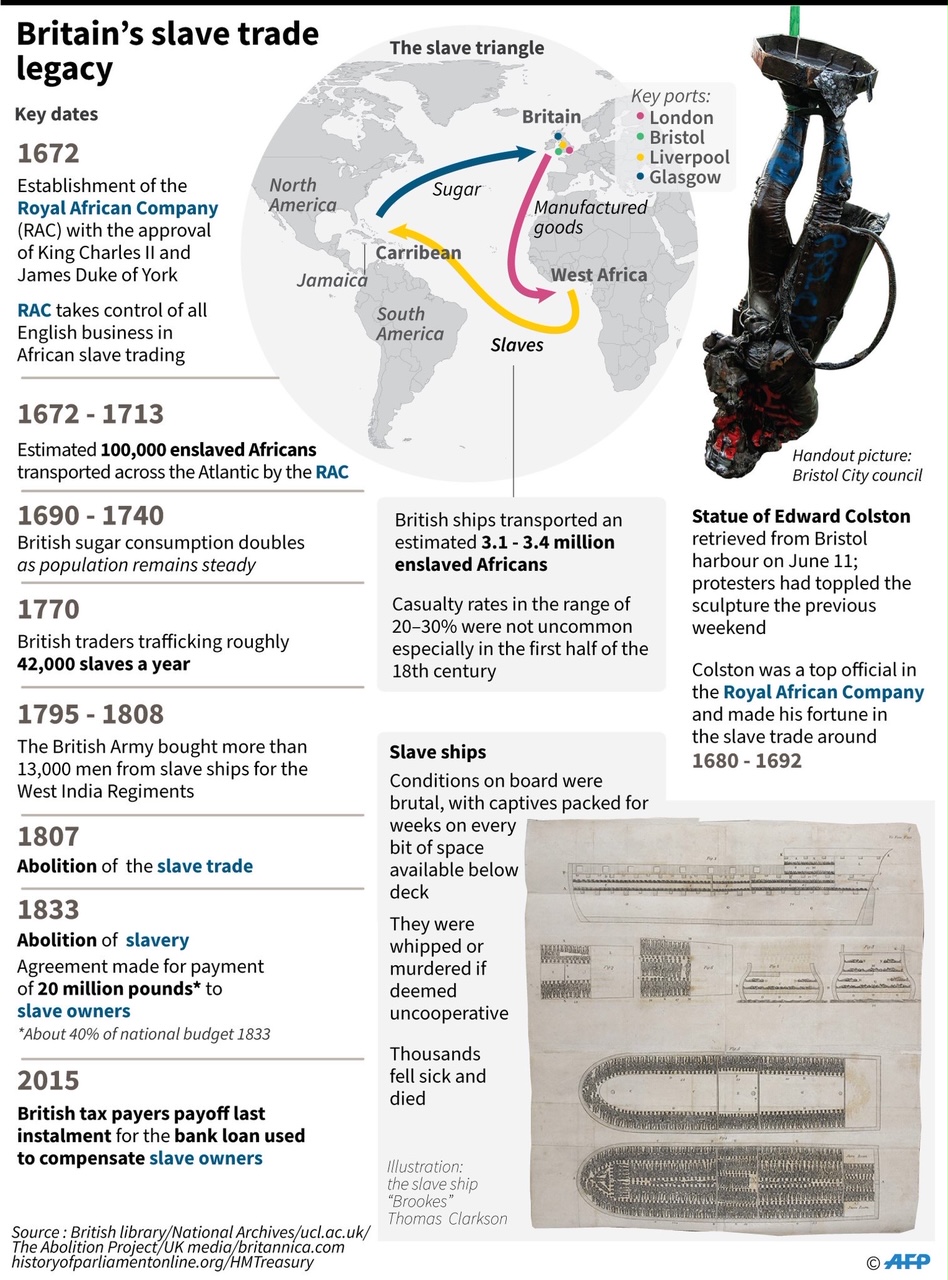

Obviously, there is a much bigger perspective. Stephanie Hare of AFP Graphics kindly provided this graphic:

There is a lot of information to parse in the graphic above but my biggest take-away was this:

2015: British taxpayers finish paying off the last instalment on the loan to compensate slave *owners*. Not slaves or descendants of slaves. Slave owners.

Meanwhile, a monument in Antwerp, Belgium honoring Leopold II, the Belgian king who plundered the Congo, will be relocated to a museum after it was defaced by demonstrators. And in the United States, statues honoring the explorer Christopher Columbus and the Confederate President Jefferson Davis were among those that were pulled down or, in Columbus’ case, beheaded.

The reason I was so intrigued by this event was because I spent a good part of last weekend re-reading some William Faulkner material by Carl Rollyson, the literary biographer.

NOTE: Carl was Norman Mailer’s first literary biographer to draw on Mailer’s unpublished letters and manuscripts as well as on interviews with the writer’s friends and foes. He assisted my cousin, an American and English literature professor in the U.S., in the research for my cousin’s monograph on Mailer and my cousin now organises the annual “Project Mailer” event which assembles Mailer scholars for one week in Macon, Georgia to discuss Mailer’s work. Carl was also William Faulkner’s first literary biographer to draw on Faulkner’s unpublished letters and manuscripts as well as on interviews with the writer’s friends and foes. Carl is considered to be the definitive biographer of Faulkner.

Hardly a day goes by without someone appropriating the statement in the graphic that leads this post and it’s usually prefaced with “Faulkner said.” Well, really, he never said it. The charter Gavin Stevens says it in Faulkner’s 1951 novel Requiem for a Nun, and like every statement of a fictional character, this aphorism cannot simply be attributed to the author. “The past is never dead” pursued to its logical conclusion is an absurdity, obliterating both present and future. In a recent blog post Carl noted:

Those who quote Faulkner do not seem to understand that he is not simply saying we live with the past, that it is some kind of fixed fact. On the contrary, Faulkner believed that depending on what we do now, in this moment, will change what the past means. He was no determinist and did not believe we could not alter the conditions of the past. Quite the contrary, he was a futurist.

It also recalls Jean-Paul Sartre (whose writing is so spot-on today) who argued:

The past takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, it seems unchangeable. Except that ultimately what the past means is what the future makes of it.

The future for Faulkner was not “closed.”

The world is imperfect and the present – from our political and civic and social institutions to the arts – is built on history that falls well short of contemporary moral standards. Our cultural inheritance is complex; the bad mixed in with the good. The Brits have to deal with the racism mixed with the towering moral heroism of Churchill. The Americans have the same issue with their Founding Fathers. Some argue that if indulged, the urge to smash monuments to a tainted past will leave us with a bleak cultural tundra and the dreary narrowing of intellectual horizons to go with it.

Which is why, as the anti-racism movements in Britain and the U.S. scream with new intensity, with new power for the cleansing of our public sphere of any reference to people linked to slavery or imperialism, many people are shuddering. Not because they believe in celebrating slavery – of course not – but because of the implications for the rest of culture if there are moves to cleanse and destroy, rather than live with, the past.

I’d argue “not so”. In addition to Carl’s work, I re-read sections of Tony Judt’s collection of essays When the Facts Change, a few Robert Saunders essays on erasing British history, and Ta-Nehisi Coates book Between the World and Me which includes a chapter on removing Confederate military statues in the U.S. So some thoughts on the Colston statue and our need to rearrange the past.

As Sauders writes:

Public statues can never be politically neutral. They are statements about who and what we honor as a society. The decision to erect (or maintain) them is an exercise of power over the public realm. As such, it carries into one age the values and power structures of another.

The problem of course is that statues inhabit the present, not the past, and are subject to its jurisdiction. Our relationship with the past – and the things we choose to honor – are going to change over time. It is certainly not an offence against history to reflect those changes in what we commemorate in our public spaces.

In his book, Coates says to remove a statue is not to “erase history”. On the contrary, statues themselves can be acts of historical erasure. The Colston Statue, for example, did not mention his role in the slave trade. It constructed a history from which slavery was written out and cast it in bronze. Colston may not have been honoured *because* he was a slave trader. But this was not thought important enough to *disbar* him from honor, or even to mention on the commemorative plaque. His statue served not to memorialise the past but actually to edit and curate it. Saunders notes:

Good history means challenging silences and evasions, not encasing them in bronze. For decades, campaigners in Britain have fought to write the history of slavery back into their public monuments: not to suppress the past, but to give a more full and accurate representation. Time and again, campaigners proposed new plaques, or contextual information, or artwork that would acknowledge the history of slavery. They sought compromise and consensus through constitutional channels. Yet time and again, those channels were blocked by obfuscation and inertia.

In the ever-flowing social media firehose I have read much of the comment that it would have been much better if the statue had come down through our constitutional entities: “The fate of public statues should not depend on whether police or protestors can muster bigger numbers”. But if you read the Bristol press, much of the blame lies with those very “constitutional entities” who for years blocked every single constitutional avenue for change, every attempt by reformers to remove or modify the Colston statue and/or the plaque. As MLK said:

Debate around public statues is not going to go away. Nor should it, for it raises profound questions about our values and the ownership of public space. So governments need to establish good-faith processes in which debate can happen – and from which meaningful change can really emerge. And despite my cynical views on political life these days, that might happen given today’s volatile polity. But I’m not as positive as Saunders who says “we might find a richer and closer relationship with our civic history, finding new stories & figures to celebrate”. History as taught in both American and British schools and universities would need a sea change.

I agree with Coates:

Statues are not holy mysteries, beyond the reach of unclean hands. Accommodations must be made. Otherwise we will turn our common spaces into a site of holy war. Charlottesville Virginia showed us that.

In the UK, many say this signals a new era of approval for the destruction or removal of historical artefacts deemed offensive. And given that most of history is offensive by current standards, a lot of destruction is in the offing. Protesters have identified 60 statues to be removed in Britain, and a statue of the merchant Robert Milligan, an 18th century slave-dealer, has been taken down from West India Quay in the heart of the Docklands he helped build.

This week someone noted the Tate galleries may be renamed, since although Henry Tate was never a slaver trader, he made his fortune as a sugar refiner, and therefore is deemed to have benefited. Oxford Council has invited Oriel College to submit a planning request to take down the statue of empire-builder Cecil Rhodes, the subject of a five-year campaign for removal. Thousands have been gathering this week at the college demanding that Rhodes must go. Some are “calling out the white supremacists protected by academic institutions” and insisting that activism against the Rhodes statue is actually a rallying cry for the “the Palestinian liberation struggle”. Given the usual craven institutional compliance, many fear these are the people now decreeing what the British public sphere should look like.

In the U.S. there is a fight in the military over scrapping the Confederate names on forts across the country.

In the entertainment word, Netflix, the BBC and the streaming service Britbox have removed David Walliams and Matt Lucas’s Little Britain and Come Fly With Me because,in the BBC’s tortuous lingo, they “include scenes where the comedians portray characters from different ethnic backgrounds”. The long-running American programme Cops has been pulled by Paramount. And Gone With the Wind (1937) has been taken off HBO Max. It will, however, eventually be returned – but with a lengthy preface and “denouncement” of its depictions of slavery. Even Fawlty Towers, one of Britain’s best-loved television institutions, has found itself a victim of the iconoclasm.

I know. As our monuments tumble or are defaced, the arts are also being plucked and censored. My cousin (the literary gent I noted above) sent me a quote from Matthew Arnold’ book Culture and Anarchy (1869) that pretty much said in order to be worth anything, art has to be kept separate from the moral and political jockeying of the social sphere. Only then can it exist as an arena for creativity and dissent; for what he called the free play of ideas. Forcing art to adhere to the contemporary political line, or expecting moral purity in its creator, destroys an essential outlet for critical freedom while also stifling the right to artistic interpretation.

In the end, today, our present vision is complexity. Yes, setting out to remove everything morally impure still visible on our cultural horizon can be deemed babyish as it is authoritarian. Just like the past itself, most people are neither wholly one thing nor the other. Dickens was a misogynist, deeply racist, a committed democrat and deeply opposed to slavery. Trollope was rabidly anti-Semitic but wrote with stunning sensitivity about questions of money, power and gender. Michael Jackson was a sex offender who abused children but produced some of the most important pop of the last century. Reducing everything to “good/bad” and ‘”agree/disagree” in the name of present social justice standards does destroy not only art and culture but makes a mockery of the contradictions and complexities of life itself.

Zoe Strimpel, the academic historian, broadcaster and blogger, lived in Berlin for a long time and she often walked through the Tiergarten, passing the statue of Richard Wagner, the obsessively anti-Semitic composer beloved by the Nazis. Having four Jewish grandparents who fled Nazi Germany and many other relations who did not make it out, she found the statue unsettling. But she recently wrote:

I am glad I can see Wagner in plain sight in the Tiergarten, and have the chance to pair his statue’s history with what I know about him. I accept that Volkswagen remains a prosperous car manufacturer despite being one of the first companies to take full advantage of forced labor during the Second World War, profiting greedily off the work of Jewish concentration camp inmates. I am glad I grew up reading Trollope and Dickens, able to enjoy their wondrous, wise prose while also wincing at their sneering at Jews. I am the richer for it all. If, in contrast, we set ourselves the task of banning all history and culture that does not toe the present political line, the road to darkest depths becomes clear.

As protests after the death of George Floyd got bigger and bigger in the United States – and then began to spread around the world – the focus of conversations in the media shifted abruptly. Now the issue was vandalism and anarchy, precisely what Donald Trump and his backers wanted to talk about as they cynically accused black protesters of dishonouring Floyd’s memory. And in the UK, it’s easier to talk about the lawless mobs tearing down statues than the crimes these monuments commemorate.

But this is nothing new. What we rarely hear about all the great revolutions of the past is that they too looked at first like spontaneous uprisings against the existing order – and they too were subject to charges of anarchy, reckless violence, puritanical revenge. So much so that the economist Albert Hirschman described the demand to “follow the process” as “the first reaction” whenever the threat of real change is on the horizon.

Read Simon Schama’s chronicles, and the first accounts of the French revolution made no distinction between its positive and negative aspects – collapsing its moral position and its violent manifestations into one. The result was that, for a long time, it was defined and smeared by its excesses. It was only the passage of time that transformed it into “a riot blessed by history”, as Gary Younge (editor-at-large for The Guardian newspaper) blogged over the weekend.

Today, it is the Black Lives Matter movement that is being discredited for not staying in its lane; for refusing to “quit while they’re still ahead”, in the words of one broadsheet columnist. But protests happen in the first place because the “proper channels” have failed – in some cases, because previous protests have also failed. When #MeToo first began, it only took a moment for women to be told to report their assaults to the authorities instead of taking their allegations public, lest they destroy a man’s reputation before he could have a hearing. But it didn’t occur to these critics that the court of public opinion was itself a last resort. When a statue falls, you don’t see the years of campaigning and lobbying and writing that went before it, and came to nothing. When Extinction Rebellion occupies central London, you don’t see the power – corporate lobbyists, complacent politicians, indifferent bureaucrats – that marginalized these concerns for so long that activists knew there was no other way. Nesrine Malik, the Sudanese-born, London-based columnist and author, blogged:

The very nature of being excluded from the spaces in which decisions are made means that the process of managing grievances is already rigged against you. The very position of black people as always appellants, never adjudicators, means that every protest will soon enough be denigrated as violent or disruptive. Their demands will always be dismissed as unreasonable, their priorities confused, their methods offputting to erstwhile allies. Politely they will be questioned: are statues really the most important thing here? May I call your attention to your pay gap? Your incarceration rates? They will be lectured about coalition-building, about easy wins that mean little in the end, and the hard graft that needs to be done if they’re going to get anywhere. Because we have processes, you see.

And these rules must be respected – because conservatives will always hold them up to stymie any change, and because liberals are afraid to admit that most of our rules and norms are neither definitive nor universally observed. They are afraid to shatter the illusion and face the reality that so many of these rules are, in fact, broken all the time by people who can get away with it: tax avoiders, labour exploiters, vote manipulators. And so it is those who cannot get away with breaking the rules who are told they must uphold what is left of this order; it is their responsibility to ensure that the slope does not get too slippery and allow us all to slide into chaos.

But as long as concessions have to be prised from the hands of the establishment, rather than reasonably handed over, we cannot live without slippery slopes. Our history may, in time, bless some riots; but it also sands the rough edges off many others, expunging the anger of martyrs and revolutionaries and telling us that their victories, over slavery or Jim Crow, were the benign gift of those masters whose morality carried the day.

The premise of change is that risks and chances need to be taken. And the movements that will be born from that demand will never be neat, and never have been. The effort to humanise black lives and win them the rights to safety and the dignity of equality may involve – among many other things – pulling down statues when it becomes clear that polite petitions and humble pleas to decolonise the curriculum will for ever go unheard. Process by its very nature is conservative. To insist that the aggrieved must “follow the rules” or lose our support is to ignore the lessons of history. Many of the rights we now take for granted were won by people who knew when the time had come to give up on the establishment. Civil disobedience, strikes, riots and boycotts are not the hijacking of process: they are its continuation by other means.

Me? I am voting for this: rather than tear it down and ban it, maybe the the lesson should be to learn to live intelligently with the past. Yes, memory, when damned or banished can allow for historical falsehoods. So footnote it as you must. Tame it. As I said above, the debate around public statues is never going away. Nor should it. It raises profound questions about our values and the ownership of public space. So governments need to establish good-faith processes in which debate can happen – and from which meaningful change can really emerge.

I thought you walked the perilous line concerning public statuary with agility and billiance. It’s a sore spot among the populace here in New Orleans, who adopt the “where will it end” tone that extends to founding fathers and slave owners like Washington and Jefferson. It is one thing to talk about the need for historical context and (clearly) quite another thing to get it done. A statue has a fixed place and can be afforded a context in the form of a plaque or adjacent statuary. Not so much a street or a city named for a Confederate. Every society stood on the necks of those who came before. We can’t celebrate that; but, can we (should we?) live with it? Great piece.

Craig, many thanks. I added a piece at the end which had been cut off. There is nothing new. What we rarely hear about all the great revolutions of the past is that they too looked at first like spontaneous uprisings against the existing order – and they too were subject to charges of anarchy, reckless violence, puritanical revenge. So much so that the economist Albert Hirschman described the demand to “follow the process” as “the first reaction” whenever the threat of real change is on the horizon. The first accounts of the French revolution made no distinction between its positive and negative aspects – collapsing its moral position and its violent manifestations into one. The result was that, for a long time, it was defined and smeared by its excesses. It was only the passage of time that transformed it into “a riot blessed by history”, as Gary Younge puts it.