Ah, the tricky (legal) relationship between a grandparent and a grandchild … and the laws surrounding social media

21 May 2020 (Brussels, Belgium) – From recreating famous paintings using just household products as part of a museum competition …

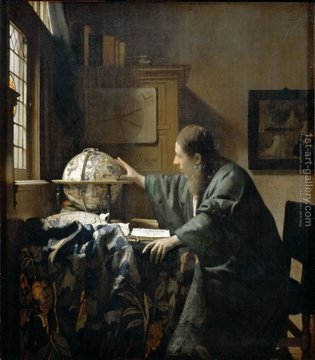

Vermeer’s The Astronomer

… or deciding you can teach the tricks of baking from your home ….

… the lockdown has prompted many of us to explore new hobbies. Mine has not been not so much a hobby. More catching-up on a reading stack long ignored, especially material on the interface between privacy and social networks. Yes, any element of data privacy died a very, very long time ago. I am more interested in the twisted application of such laws as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which seems to continue proving that old maxim “be careful what you wish for”.

I stumbled upon a case from The Netherlands [full case here, in Dutch; this post will summarise the main points], which ordered a person to remove from her Facebook and Pinterest accounts a picture of her underage grandchild, at the request of the child’s mother (the defendant’s daughter). This raises the question what rights, if any, a person in such a position should be able to claim to post such pictures.

The case

The decision was rendered in preliminary relief proceedings and is therefore succinct; it is also anonymised so I will refer to the parties using letters. A is the mother of B, who is the mother of C and two other children. Due to a fight, A and B have not spoken to each other for years. For a period of seven years, C lived with A and her husband. Thereafter, C moved in with his father, the ex-partner of B. B filed suit against A, requesting that she remove from her social media profiles all pictures of her children, since neither she nor her ex-partner consented to publishing them.

A removed all such pictures, but asked the court to let her keep online one picture of C because she has a special relationship with him after taking care of him for several years. The court granted B’s request and ordered A to take offline all pictures from all of her social media accounts. It assessed the claims under the GDPR. No copyright issues were at stake because neither party claimed authorship of the pictures.

Article 2(2)(c) GDPR exempts from its material scope processing of personal data “by a natural person in the course of a purely personal or household activity”. The court acknowledged that “it cannot be excluded” that placing a picture on a Facebook or Pinterest page might be exempted from GDPR scrutiny on the basis of this provision, but held that it had not been established that A’s pages were inaccessible to the general public. The court added that it remained unclear whether the pictures could be found through Google, and that in the case of Facebook it cannot be excluded that the placed pictures can be spread and downloaded by third parties.

This largely decided the case. The Dutch act implementing the GDPR states that in the case of minors, their legal guardian must consent to the data processing. Since C is a minor and his parents expressly disagreed with keeping the picture on A’s Facebook page, it had to be taken offline.

Analysis

The case is a great illustration of how difficult it often is to comment on decisions merely on the basis of their text: several facts that remain unknown to us may have severely affected the outcome. In particular, the nature of the picture, or how the case was argued and we can’t fully understand the unfortunate family circumstances in which the litigants find themselves, nor what caused them. Even so, a number of issues stands out.

Is social networking a personal or household activity?

First and foremost, there is the matter of the personal-or-household-activity exception. The exception appeared already in the GDPR’s predecessor, and the most authoritative interpretation remains the Court of Justice EU (CJEU)’s decision in C-101/01 Lindqvist. Referring to examples of “correspondence and the holding of records of addresses” cited in the Directive’s preamble, the CJEU there ruled that the “exception must therefore be interpreted as relating only to activities which are carried out in the course of private or family life of individuals, which is clearly not the case with the processing of personal data consisting in publication on the internet so that those data are made accessible to an indefinite number of people.”

It has been argued that in current times, where for many social networks are the primary outlet for personal contacts and expression, this is an unduly narrow interpretation of the exception. For instance, the Article 29 Working Party (WP29) issued a guidance paper in which it discussed the ascent of social networking and the extent to which data processing on such sites should be considered strictly ‘personal’ [click here]. According to WP29, “making information available to the world at large should be an important consideration when assessing whether or not processing is being done for personal purposes. However, this should not in itself be considered determinative”.

Recital (18) of the GDPR reflects this recommendation, stating as it does that “social networking and online activity undertaken within the context of [household] activities” should fall within the exemption of Article 2(2)(c). But then one wonders why the court adopted such a restrictive interpretation of this exemption.

I also wonder whether in a case as was before the Dutch court it might have been preferable to order the defendant to close her Facebook and Pinterest pages to the public. If the concern was that the pictures could be viewed by an indefinite number of people, this would solve that problem; and as will be discussed below, the defendant likely had countervailing rights that entitle her to place the picture online.

An order to close off the pages from the public, rather than an order to remove the pictures altogether, might therefore have been mandated by the general principle of proportionality, as it appears in the case-law of the CJEU and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). For instance, in C-484/14 McFadden, the CJEU sought a remedy that would least infringe the defendant’s rights, and in 26839/05 Kennedy v. UK the ECtHR accepted a surveillance regime only subject to provision of sufficient safeguards against abuse. To be sure, McFadden was not a privacy case and Kennedy related to mass surveillance, but in both cases the outcome was mandated by a desire to reach a fair balance between the fundamental rights involved. A similar approach might be necessary in a case like this one.

Which rights should be considered?

If the household exemption applies, the case falls outside the scope of the GDPR and should be assessed under a general balance of rights inquiry. But which rights, and whose? On the part of the minor, it seems clear: his right to privacy, as protected by Article 8 European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) and Article 8 of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights.

But the boy’s grandmother’s fundamental rights might well be at stake, too. There is, of course, the right to freedom of expression – Article 10 of both the ECHR and the Charter – but that somehow doesn’t fully capture the situation at issue. Posting on one’s social media page a picture of your grandson, who lived with you for seven years, is not ‘just’ an expression like any other. In the age of social media, it expresses a personal connection between two people.

In an excellent book about social media and the law which I have noted before, Professor Lorna Woods has argued that “when many spend a lot of their time on social media, internet use is about developing personality and identity”. She therefore submits that social media expressions may be protectable not just by Article 10 ECHR, but also Article 8: the right to family.

What is more, the ECtHR has repeatedly held that the relationship between a grandparent and a grandchild is protected under this same provision [see, e.g., 63190/16 Beccarini and Ridolfi v. Italy]. The court should have thus considered A’s protected interests under Article 8 ECHR in posting a picture of her grandson before ordering her to take it offline. Surely that would make the matter more complex, but simply dismissing the grandmother’s position would result in an imbalance in the protection of fundamental rights, given the increasing role the Internet plays in personal and social lives.

A final question: what about the rights of B, the mother? Assuming she was not in the picture, it is questionable whether she could invoke rights of her own in support of her claim to take offline the picture of her son. If, from a rights perspective, her position is limited to that of legal guardian, the inquiry becomes even more complex. After all, it is not clear that her animosity towards her mother can impose limits on the family life her mother enjoys with her grandson.

But here, too, we simply don’t know enough about the case, so further speculation is probably best reserved for the next case sure to come.