This is a continuation of last week’s post entitled “Mark Zuckerberg begs for Facebook to be regulated. Yes, really. He said so.” which you might want to read for background.

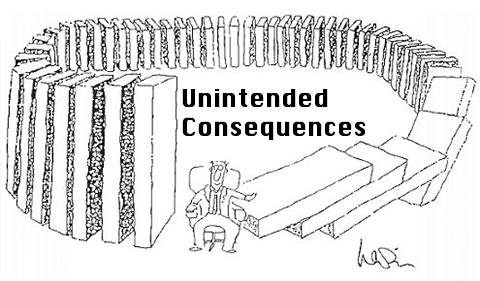

In this piece, a deeper look at the regulation of technology and tech’s relationship to government, with an attempt to unpack the just-launched EU “digital agenda” — an agenda fighting the tech battle with one hand tied behind its back. Just as Britain after Brexit has become a polity plagued by a fear of its own rejuvenation, the EU is a polity plagued by a fear that it has lost its digital sovereignty. And oh, woe and behold – it has brought upon itself the spectre of unintended consequences.

28 February 2020 (Brussels, BE) – Europe wants to keep writing the rules of the digital future, but a reality check may be in the offing instead. The EU’s ambitions are grand, but matching the power of Silicon Valley, Washington and Beijing won’t be easy.

The EU’s latest bid for power in the online realm is a five-year digital policy blueprint unveiled with great ceremony last Wednesday, one centered on data and artificial intelligence and patently designed to beat back American and Chinese dominance in tech. It’s meant to show how the bloc could harness its biggest competitive advantage – the world’s largest single market – to improve its economy and build a green future. And given the EU’s record as a serious player in digital politics, if not digital innovation, its latest brainstorms were digested eagerly in D.C. and California. But with undisguised doubt.

Because the obstacles to achieving its newest grand ambitions are daunting: the power of Silicon Valley, Beijing and increasingly Washington is born of deep reserves of capital, talent and research capabilities that Europe can’t match. The EU is also internally divided and short on money and short on will to turn a Brussels policy document into reality.

But before we get into the weeds and parse all of this stuff, some foundational elements.

Getting to “obviously” takes a lot of work and time. As I indicated in Part 1 of this series, as a research/background note, writing something like this requires a very extensive “consumption” regimen. You need to start with some foundational texts (a list of my sources for this 2-part series can be found at the end of this post), plus numerous conversations and interviews at multi-faceted technology conferences and technology trade shows. Having done that, you need to read the remainder of this piece mindful of these points:

1. Data privacy and data sovereignty did not die of natural causes. They were poisoned with a lethal cocktail of incompetence, arrogance, greed, short-sightedness and sociopathic delusion. Tech has become the person in the room with us at all times. By introducing technology so very rapidly into every aspect of the human existence in such a preposterously short historical period of time, Big Tech has thrown a metaphorical person into all our lives.

2. When a technology is introduced into society, unimpeded, through private enterprise, and then quickly adapted and adopted, the game is over. We (they?) have built a world, a system, in which physical and social technologies co-evolve. How can we shape a process we don’t control?

3. And all those lawyers who say “we must do something about privacy!” are … pardon my French … full of merde. Their brethren and cohorts are equally guilty of forming their own logic of informational capitalism in comprehensive detail. Look at the legal foundations of platforms, privacy, data science, etc. which has focused on the scientific and technical accomplishments undergirding the new information economy. Institutions, platforms, “data refineries” that are first and foremost legal and economic institutions. They exist as businesses; they are designed to “extract surplus”. Gramsci was speaking truth when he said that, “the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear”

4. And when a technology is introduced into society, unimpeded, nobody can catch up. With the continuing development of computer vision and video analytics, facial recognition may ultimately turn out to be one of the more benign applications of camera surveillance. Put another way, facial recognition is just part of a much larger program of surveillance – equipped with higher scale and granularity—associated with cameras, microphones, and the multitude of sensors in modern smart phones. As these systems become more sophisticated and more ubiquitous, we are likely to experience (actually are experiencing) what Big Tech calls “phase transition” – the transition from collection-and-storage surveillance to mass automated real-time monitoring. At scale.

5. What sets the new digital superstars apart from other firms is not their market dominance; many traditional companies have reached similarly commanding market shares in the past. What’s new about these companies is that they themselves ARE the markets. They have introduced technology so very rapidly into every aspect of the human existence in such a preposterously short historical period of time, that the “regulators” cannot cope.

The “4 Horseman of the Digital Apocalypse” … Google, Amazon, Apple and Facebook … have left the barn.

There is also a 6th point but it applies more specifically to the EU. Europe is still in thrall to the analogue mindset. The five-year digital policy blueprint unveiled last week is written as if the technology age will not develop. The EU is culpably complacent, protective about the challenges of the digital age. Consequently, it is being left behind. Reflect on the relative decline of Nokia (it may need to merge or sell itself) and Ericsson. It seems desperate to hang on to what it has, what it understands – at the expense of future prosperity. Jack Mabry, a telecom analyst with IDC, reminded me of the story about a leading German telecom manufacturer who in the late 1990s produced the most sophisticated analogue telephone exchange ever seen – when digitalisation was already the wave of the future and advancing exponentially.

The digital revolution started in the last century, but most of its economic impact is still ahead of us. A growing proportion of trade between now and the end of the century will be in data. As Wolfgang Münchau has written (he is a German journalist who co-founded Eurointelligence, a highly regarded internet-based platform for news and analysis of the Eurozone’s politics, finance and economics, and writes frequently in the Financial Times):

Just-in-time global supply chains of physical goods are the defining characteristic of early 21st-century globalisation. But advances in 3D printing will make it possible for production to become more localised, thus reducing the need to ship components and goods across borders. Global supply chains are being upended in industry-after-industry. When you trade data, geographic proximity becomes irrelevant. Regulation becomes an algorithm. The idea of the EU as the global regulator would depend on technology not advancing.

The EU’s absence in any element of the digital age’s data architecture is by choice, not necessity, as I will detail below. The EU could have carved out a niche for itself. France and Germany still have some of the best mathematicians and engineers in the world. But politics intruded. The EU chose to prioritize data protection over technology (especially artificial intelligence) investment. It is why I think this marks the end of an era. For 15 years the EU has served as the world’s leading digital police force, making up for its lack of massive tech companies by wielding tools such as multibillion-dollar antitrust fines, tax claw-backs and laws like the General Data Protection Regulation. And the EU Commission remains perplexed why Big Tech behavior “has not changed” – the thought recently expressed by Margrethe Vestager in an unguarded moment. She has dual roles: the EU’s Competition Commissioner, and also as Commission Executive Vice-President for dealing with Europe and the Digital Age.

And before I get into the weeds of the EU’s new digital agenda, just a few more foundational bits.

To properly understand this stuff you need to understand what Paul Dourish calls “the brute materiality” of wires, servers, connectors, and heat. Software elements have their materialities too, and examining the material configurations of computation and representation shows how their constraints are entwined with computational practice. As I have noted before, if you really want to understand the digital architecture within/under which we live, you need to get into it and sometimes just “do the tech”. Too much of what I read is like listening to my maiden Aunt tell me about marriage.

I will discuss this all in more detail in “The death of data privacy, and the birth of surveillance capitalism: how we got here” (my work-in-progress) but herein a few points.

Those sneaky data collection tricks: Part 1

Years ago when running my personal website I used to have my own scripts for figuring out exactly what search terms Google users were searching for. They were a query string, something like “http://google.com?s=data+theft+reality+videos” which you could easily parse to figure out that the person who found you was searching for data theft stories. Easy enough.

But then about 10 years ago (maybe a bit longer) Google started “encrypting” their search terms, for our safety (of course), so the Google URL would instead be “http://google.com?s=asdJNjnsssall” or something to that effect where the data was obfuscated so you couldn’t read it yourself. Only Google knew what their users were doing and the gobbledygook in the referrer url gave you nothing as a website owner.

Of course there was a solution: you could install a small Google Analytics script on every one of your website pages, and this would give you really cool real time metrics of exactly who was visiting your site and you wouldn’t need to rely on crude query string parsing. Brilliant, yes?

Well, the difference is that Google also got hold of the data and were able to use their analytics data to see exactly what your users were doing on all of your pages, and all of everyone else’s pages (view the “source” link in any web site you read and you’ll see everybody is using it right now). By then of course Google was offering its own advertising platform, Google Adwords, which now has access to basically all behaviors of all users on the web (as everyone who wants SEO must have Google Analytics installed).

So Google thereby leveraged its dominance in search to make you want to install Analytics on your site in order to do effective SEO, to the point of them having so much data on your site (and users and their internet histories) that their advertising platform Ad Words simply couldn’t be beaten for effectiveness. I do not publish Google Ads on this blog but I did have it once on one of my commercial sites because their conversion rates are much better than everyone else.

The take-away? It’s an effective data monopoly and no one else stands a chance to compete, unless they can somehow get hold of the same data that Google has access to which is why the EU Commission is teasing out its “European strategy for data” to explore “the need for legislative action” to push companies towards sharing and pooling data. That proposal is dead-on-arrival, an issue I will discuss in my longer piece to come.

Those sneaky data collection tricks: Part 2

For my normal day use, I use two iPhones and an iPad Pro. This set is my “public” technology set, the ones I use for general non-critical emails and phone chats and to follow social media and consumption of news websites, and on which I have 80GBs of music stored (nothing in the cloud). One of the slyer tactics harnessed by companies is using trackers. These sit all over the web and try to work out your surfing patterns by tracking your browser’s digital footprint. To block that, I use browser extensions such as Privacy Badger, which blocks trackers, and AdNauseam which clicks on random ads as you browse to confuse firms that monitor you.

I have two other iPhones. Both are “anonymous” meaning neither device ID is linked to me. They were programmed by my cyber security mavens (and clients) at F-Secure and Palo Alto Networks. One I use for my heavy journalism work when I do not wish to be tracked/monitored and it has encrypted messenger and email accounts.

The other is for my “fun stuff” research. It is where I can set up false personas (there is a skill to doing that) to see how all this data tracking, data exchange works.

For instance, as I have noted in previous posts, Facebook’s tracking pixels and social plugins – aka the share/like buttons that pepper the mainstream web – have created a vast tracking infrastructure which silently informs the tech giant of Internet users’ activity, even when a person hasn’t interacted with any Facebook-branded buttons. Facebook is also able to track people’s usage of third party apps if a person chooses a Facebook login option which the company encourages developers to implement in their apps – again the carrot being to be able to offer a lower friction choice vs requiring users create yet another login credential. The price for this “convenience” is data and user privacy as the Facebook login gives the tech giant a window into third part app usage. The company even uses a VPN app it bought and badged as a security tool to glean data on third party app usage. It recently stepped back the use of that VPN a bit after a public backlash – though that did not stop it from using a modified version.

Facebook claims this is just “how the web works”. Other tech giants are similarly engaged in tracking Internet users (notably Google). But as a platform with 2.2BN+ users Facebook has got a march on the lion’s share of rivals when it comes to harvesting people’s data and building out a global database of person profiles. It’s also positioned as a dominant player in an adtech ecosystem which means it’s the one being fed with intel by data brokers and publishers who deploy tracking tech to try to survive in such a skewed system. And it is used to game the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) … which EU regulators now, finally realize … making the GDPR a bigger pain to enforce. I will address some of the GDPR issues below but save my cannon fire for a longer chapter to come.

I then take these fake personas and go to organizations like the Tactical Technology Collective (it is based in Berlin, Germany) that can show me just how much the tech giants know about that false persona, where that persona’s data travels, etc. There are a number of entities that do this type of work. I will detail them in a subsequent post.

Now, on to technology regulation.

Technology and government. An incestuous relationship. At least in the U.S. You need to start with the first important factor – venture capital. Through the books I read (noted in the Postscript at the end of this post), I reached back almost 200 years to marshal a wealth of quantitative evidence that tracks the evolution of high-risk investing in America – the envy of every EU start-up. The modern, professional venture capital industry found its Valhalla in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Side note: and why did Stanford University become that “third” partner? Thanks to the introduction of radio more than 100 years ago and the emergence of a community of amateur techies (“ham” operators) interacting with the US Navy, a microelectronics components industry serendipitously emerged on the peninsula south of San Francisco. Before broadcasting had even been imagined, the killer app for wireless communications had been ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore interaction. Years before becoming the dean of engineering at Stanford University after WWII, Frederick Terman, as a very young professor of radio engineering, was heavily involved in that emerging microelectronics industry. He realized that the university could be positioned as a critical player and positioned the university so, adroit at the interplay between the private sector and the government. Read almost any book about the creation of Silicon Valley and you will see he is widely credited as being “the father of Silicon Valley.”

This all provides the deep context for understanding the sources of today’s digital revolution that is now redefining economic, political, social, and cultural life around the world.

Yes, the “first partnership”, broadly recognized in the popular culture, is between the entrepreneur and his (it is almost invariably a male) financial backers – that is, the VC industry.

But the second partnership … between the entrepreneur and the United States government … is perhaps more important because it would eventually involve the hoary beast, regulation. That partnership is not new. The environment of “small government capitalism” (to use Hyman Minsky’s term) has a long history. We saw it in full flower in the construction of transformational networks of physical infrastructure – namely, railroads and electricity grids – they were able to summon the resources of the state, whether through public-land grants, construction subsidies, or monopoly franchises to for-profit “public” utilities. Then came World War II, from which emerged the enlarged American welfare and warfare state. This marked an inflection point in the evolution of the American venture capital industry, and the role of government.

We began to see its modern manifestation in the 1960s with the build out of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the U.S. space program. But that was in fits and starts. The modern government-private sector love fest really got its mojo with Richard Nixon. In 1971 Nixon launched the “War on Cancer”, positioning the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to become the engine of the genetics revolution. The NIH began looking to the private medical sector to help and began pouring in large investments. As in the case of the digital revolution, it was the US government that built the medtech platforms upon which entrepreneurs and VCs would later dance and take their bows.

The U.S. Department of Defence (DOD) saw an opportunity and took its cue and the DOD-private sector technological sponsorship emerged. It was a relationship that would have probably wet the collective panties of the EU technology community. The DOD funded upstream research, and then became an early, collaborative purchaser of the technological fruits before they had become affordable or reliable enough for commercialization. The DOD’s procurement role, for everything from microprocessors to mission-critical software, is often underestimated relative to the significance attributed to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (more commonly referred to as DARPA).

Telecom technology would become all-important and it was hoarded by the U.S. government for years before the release to general consumers. Government-protected monopolies dominated the landline phone business. We would eventually learn that the government protection and investment came at a price – government agencies were given free access to telecom networks. But that has been known for years. My favorite quote from the 1997 movie “Enemy of the State” :

“The U.S. government’s been in bed with the entire telecommunications industry since the forties. They’ve infected everything. They get into your bank statements, computer files, email, listen to your phone calls. Every wire, every airwave. The more technology used, the easier it is for them to keep tabs on you. It’s a brave new world out there. At least it’d better be.”

But then the growth and complexity of communication and information technology began to have an immense, uneven economic and political and social impact. Issues of regulation came to the fore. I do not have the space (nor inclination) to provide a detailed history of the development of the various telecommunications and other information technology acts legislated to combat these issues. And let’s leave Edward Snowden out of this for the moment. But it is important to note that in contrast to prior technological eras – marked by inventions such as the railroad, telephone, automobile, and television – the age of digital technology has progressed for several decades with remarkably little regulation, or even self‑regulation.

This hands‑off attitude had a reason: innovation. It allowed the U.S. to become the primary leader in the innovative digital infrastructure and products that are now core to everyday life. This innovation mostly occurred with startups shielded from legal constraints. The digital revolution matured with the establishment of the Internet, a potentially limitless environment for communications and commerce. In the manner typical of capitalism, recognition of this new potential expressed itself in a speculative explosion that financed both the deployment of the necessary network infrastructure and a Darwinian exploration of the new economic space that had been created.

On the opposite side of this picture was Europe.

For Europe, there was a gear shift in European digital policymaking in which lawmakers felt they could eagerly exported to the rest of the world (excluding China) tougher privacy standards, competition rulings and calls for tighter policing of online content. The point was to establish Brussels as a global first-mover on tech regulation, an area where Washington D.C. largely stood still.

Strangely enough, the EU had the powers they needed to help local technology startups grow. They could have revamped the Continent’s complicated labor laws that vary widely between countries, overhauled how workers for fledgling companies pay tax on potentially lucrative stock options, and invested heavily in the region’s often creaking digital infrastructure. But as a source in the EU Commission told me:

Such practical policymaking doesn’t win headlines or votes. European policymakers reverted to type by promoting a 21st century version of privacy and protectionism that keeps foreigners out and which will mostly help traditional companies just as they’re facing increased competition from upstart digital rivals. It will do nothing to improve Europe’s standing in the global digital race against China and the United States. But it plays well to the home crowd.

Even now when I scan the European press, all I see are alarm bells due to Europe’s ever-growing dependence on foreign tech companies. A new generation of policymakers embodied by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen wants to take things a step further – by taking more active measures to protect Europe’s market. They see how China and, to a lesser extent, the United States have used economic policies to promote national digital champions. The thinking in Brussels now holds that, if Washington and China are throwing out the rulebook on international trade and support for home-grown industry, Europe might as well start getting more assertive, too.

That means using every trick in the book to give the 27-member bloc a fighting chance to compete globally, including blocking potential foreign takeovers in so-called strategic industries, promoting government-funded tech initiatives and rewriting antitrust rules to allow local players to gain global scale to take on foreign competitors. As more of the economy is powered by online data, EU policymakers are questioning why most of these valuable data flows run on digital infrastructure owned by the likes of Amazon and Google. Until somebody says “we had a chance to build our own, but we didn’t”.

The biggest fear is that U.S. dominance of so-called cloud computing could leave the region vulnerable to lax privacy standards and see local competitors miss out on an industry that is expected to be worth half a trillion dollars globally by 2023, according to IDC.

Note: it’s not as if the EU has abandoned investment, but it is half-hearted. The Germans and French have thrown their backing behind Gaia-X, an EU-backed cloud-hosting service, to reduce the region’s reliance on foreigners. It has its points but sounds more like tech envy. I am reminded of the countries’ joint efforts to create a European rival to Google, known as Quaero, which was quietly scrapped in 2013 after receiving millions of euros in government grants with little, if any, impact on the search giant’s dominance. For Michael Jackson, an American venture capitalist who has spent more than a decade living in Europe, all of these plans epitomize the region’s ham-fisted tactics to help the local digital economy.

So we heard over the last number of years a demand for “technological sovereignty”, clearly for the benefit of legacy players, not to help Europe compete. It’s the same old story that we’ve heard before. But there were rumblings of “we need a better plan!” and so the EU digital agenda was unveiled last week.

Last week the EU’s executive arm unveiled a series of proposals laying out the bloc’s approach to data, artificial intelligence and platform regulation over the next five years and beyond. The flurry of policy initiatives aims to wean Europe off its dependence on foreign-owned tech companies while bolstering the bloc’s own tech sector, with the aim of becoming more competitive against rivals in China and the United States. Presenting the package, which is made up of three documents, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen underscored that technology should comply with people’s rights:

“We want the digital transformation to power our economy and we want to find European solutions for the digital age”.

Why are there three documents instead of one? The answer is a combination of policy and politics, with top EU officials all keen to oversee different aspects of the plan:

1. The White Paper on artificial intelligence originates with von der Leyen’s promise to introduce legislation within her first 100 days in office. Officials quickly agreed that it would be premature to pass hard laws within that timeframe and instead settled on the idea of releasing a White Paper setting out the path forward.

2. Thierry Breton, a Frenchman and former CEO of tech company Atos, is behind the second document, which focuses on how the bloc will better exploit data to support innovation and entrepreneurship while also bolstering protections.

3. Finally, in order to link the two papers together into a broader narrative that would expand on other issues including competition rules and the Green Deal, the Commission ordered up a third document entitled “Shaping Europe’s digital future” that aims to act as a 5-year policy roadmap. That’s under the control of Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice President of the European Commission for a Europe Fit for the Digital Age, and European Commissioner for Competition.

Much of the fine print for legislation will depend on feedback the Commission is set to receive in the coming months from industry, civil society and national governments. The EU’s executive arm could decide for example to update the product liability directive, which creates a legal responsibility regime for defective products.

At the same time, the Commission argued in its White Paper that high-risk AI technology should undergo rigorous testing before it can be deployed or sold within the EU’s vast internal market, pitching the introduction of so-called “conformity assessments” for AI systems that pose significant risks in areas including recruitment, health care, transport and law enforcement. (The AI piece of this puzzle is especially tricky and needs a more detailed post so I will reserve comment except for some general points I make below).

Over the last 10 days I worked my way through all three pieces of this new digital agenda and I understand the point made by many critics: this is all about European regulators playing wack-a-mole in a disguised attempt to extract rents from the Big Tech giants. Huge fines (continue) to play a big part in all of this. But I live in Europe (bouncing between three countries, actually) and I used to travel very often to the U.S. I have experienced first-hand that most of my American colleagues totally misunderstand the intensity of the privacy movement in parts of Europe, especially Germany, Central and Eastern Europe. Privacy is a key issue here.

The U.S. regulators (if they see this through this execution) might be on a better track than Europe as they seem to be focusing on prohibiting the Big Tech players from further acquisitions and, possibly, forced divestitures. Less focus on fines. But that won’t satisfy the Euro bureaucrats because they have failed utterly to foster the growth of home grown competitors.

And there was, understandably, a rolling of eyes. It was 10 years to the week since Brussels began its first competition investigation aimed at restraining the burgeoning online power of Google. If you wonder what the EU trustbusters have achieved in all the cases and the years that followed, you are not alone. The search company’s rivals in that first case – into online comparison shopping – still complain about the ineffectiveness of the supposed “remedies” the EU ordered, and Google’s appeal against a €2.4bn fine was only heard this month. In the meantime, the company’s revenues have grown sevenfold and its influence on online activity continues to grow, seemingly unrestrained. The GDPR has … contrary to intention … made it stronger (see section further below).

That makes the new data-sharing principles … a major piece of the “unveil” last week … all the more important. European regulators have set their sights on cracking open the data silos that have helped to reinforce the power of the dominant tech companies. But while forcing more sharing of information to open up digital markets may sound like a good thing, it will be extremely difficult to break the hold of the dominant tech platforms.

What Brussels has sketched out is a two-pronged “data share” attack. So I’ll open this segment by quoting from Richard Waters of the Financial Times (their chief technology editor) who laid it out in a blog post last weekend:

One prong: it targets classes of data that can be unlocked to ensure competition in very specific, high-value markets that might otherwise fall under the sway of Big Tech. There is a direct parallel here with personal banking information, which must already be shared under European rules. The clearest example concerns the many different types of health and wellness data. Someone with a hoard of personal information generated by a fitness tracker, for instance, might want to make that information available to another health app. With the right level of user control, this could open the way for innovative companies to build new services on top of the digital economy’s most important raw material.

The second prong is industrial data, to help companies compete.

This is all well and good. But it does not deal with the fundamental problem of Big Tech’s data power, and one which will require action on a different front. As the EU described it in its white papers, the largest online platforms derive huge benefits from the “richness and variety of the data they hold”. Their power comes from the range itself, rather than any single class of data, with different types of information being combined to yield insights. Volume also matters: the power of big data lies in being able to discern patterns and train machine-learning models. Quoting Waters:

Opening this kind of data up to promote greater competition would be neither easy, nor particularly desirable. Much of the data collected by Big Tech concerns how individuals interact with their services, or other information gleaned from observing online behaviour. It will be legally challenging to force companies to hand over data like this that they generate themselves, and rightly consider a valuable corporate asset. The same goes for the insights they derive from their observations.

Trying to free up this kind of information to promote greater competition also risks running headlong into … how ironic … the rival goals of privacy regulators. Europe is less than two years into its GDPR crackdown on the permissive data-sharing economy – something that risks hampering freer competition, dismissed by the drafters of the GDPR but now faced in the real world.

Note: there is another issue here which I more properly address in a separate section below. That concerns the limits that have been put on the use of third-party data, or information that a company has not collected itself. GDPR has a large focus on this. But those rules played right into the hands of a company such as Google that has no shortage of first-party data, thanks to its ownership of several services that each reach more than 1bn people. The search company said recently it planned to outlaw third-party cookies in its Chrome browser within two years (but it is not quite executing on that, surprise, surprise; more in a subsequent post). That may give users more confidence they are not being tracked, but it made life much harder for Google’s rivals so they just dumped “3rd party” and moved into the Google camp.

Brussels says it will deal with this wider data issue in the context of its broader review of the dominant online platforms. That is a looming battle that is starting to assume titanic proportions – though past experience suggests that, when it comes to limiting the power of Big Tech, it might be best not to expect too much.

The race for tech supremacy between the U.S. and China has driven Europe to look for “data sovereignty.” It can’t win a head-on battle in this field. “Technological sovereignty” is also one of the European Union’s buzzwords of the moment, conjuring up an image of a safe and secure space for zettabytes of home-grown data, free from interference or capture by the U.S. and China. Both France’s Emmanuel Macron and Germany’s Angela Merkel have used the phrase to kick-start all sorts of initiatives, from artificial intelligence programs to state-backed cloud computing. The Von der Leyen used it last week multiple times.

It’s a noble goal, and I understand it, only because it acknowledges Europe is anything but technologically sovereign right now. The internet behemoths are in America and China – Alphabet (Google), Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba Group. Holding Ltd. An estimated 92% of the Western world’s data is stored in the U.S., according to The Centre for European Policy Studies, a think tank based in Brussels which puts out some well regarded studies. China accounts for more than one-third of global patent applications for 5G mobile technology according to the GSM Association which organises the Mobile World Congress and is an industry organisation that represents the interests of mobile network operators worldwide. Amazon in its latest 10K boasts that 80% of blue-chip German companies on the DAX exchange use its cloud services business AWS.

The trigger to do something about it is the race for supremacy between Beijing and Washington, which is spilling over into the tech sector and undercutting the EU’s ability to protect its turf. Trump’s ban on Huawei Technologies Co. and his attempts to bully allies into doing the same was a wake-up call, however valid his security concerns. The U.S. “Cloud Act,” which forces American businesses to hand over data if ordered regardless of where it’s stored, was another. Both China and the U.S. see the EU as an easy mark in the global tech tussle. And they’re right.

Europe’s problem is that recapturing sovereignty is neither easy nor cheap. Take cloud computing, one area I noted above where France and Germany are eyeing the building of “sovereign” domestic infrastructure for use by national and European companies. This is a $220 billion global market dominated by U.S. suppliers with market values of close to $1 trillion, which invests tens of billions of dollars every year on infrastructure. Their power isn’t just technological: when Microsoft Corp. spends $7.5 billion on an acquisition such as GitHub, a forum for open-source coding, it’s bringing valuable developers into its own orbit. Likewise, Amazon’s AWS has the scale, cheap pricing and perks that lock in customers.

France and Germany won’t win a head-on battle in this field. Paris is still smarting from a failed attempt years ago at building a sovereign cloud for the princely sum of 150 million euros ($165 million). Germany has Gaia-X, which looks like a common space for the sharing of data by the leading lights of the DAX , from SAP SE to Siemens AG. It’s hard to see how such initiatives will lead to true digital sovereignty, though; not just because of a lack of serious investment, but because it’s hard to avoid using U.S. cloud tech.

Still, I am not saying it would be a bad thing if this trend led to France and Germany collaborating more – laying the groundwork for more ambitious spending – and to Brussels doing what it does best: setting the rules of engagement for tech companies everywhere. That’s exactly what Ursula Von der Leyen and Margrethe Vestager were banging on about last week: demanding tougher enforcement of data protection laws and taking a consistently muscular approach to antitrust violations by the Silicon Valley and Seattle giants.

No, it’s not sovereignty. Because without competitiveness, sovereignty cannot be reached. Non-competitive application results in economic loss, eventually no application altogether, no wealth creation and no sovereignty. Europe had non-dependent access to search engine technology, but lack of competitive application at scale in the Quaero debacle (which I noted above) resulting in a permanent lack of sovereignty. Europe needs to support its vertical industry players, especially to apply AI at scale. Efficient ecosystem competition on a European level will be crucial for any competitive ecosystems to emerge. The Darwinian process proven successful in the digital sectors in the US serve as the example.

As I have noted numerous times before, when it comes to privacy regulation, the legal tech industry lives in its own reality, divorced from the way the world really works. It is akin to Steve Jobs’ “reality distortion field”. If you go to either of the industry’s premier events, Legalweek or ILTACON, the GDPR and the new California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) are presented as:

“YOU MUST COMPLY WITH THE LAW!!” But to be fair, that’s fine. There is a need for that. And after all, these are trade shows. People are there to sell you stuff. Compliance products and services. You are not there to be educated. Although the compliance vendors at Legaltech must be singing and dancing: there is lots of CCPA compliance work coming (see the last paragraph of this section).

To know how privacy legislation and technology regulation is really being handled by companies, how it is affecting the real world, how data architecture really works, etc. you need to attend events like Black Hat, or DEFCON, or the Mobile World Congress, or the Cannes Lions advertising conference, or Adweek workshops, etc.

The GDPR

When the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) rolled out there was dancing in the streets. At almost every legal and technology event everyone emphasized that (finally) “control” of personal data was coded into law, and it was the core to privacy. There was a need for data minimization. For technology vendors, catnip once again. Easy concepts to understand. Easy to sell “solutions”. Easy tech to explain.

But as GDPR enforcement and compliance rolled out it dawned on many that control was the wrong goal for “privacy by design”, perhaps the wrong goal for data protection in general. Too much zeal for control dilutes efforts to design information protection correctly. This idealized idea of control is impossible. Control is illusory. It’s a shell game. It’s mediated and engineered to produce a particular control. But the folks that built our data architecture knew design is everything. The essence of good design is to nudge us into choices. Asking companies to engineer user control incentivizes self-dealing at the margins. Even when good intentioned, companies ultimately act in their own self interests. Even if there were some kind of perfected control interface, there is still a mind-boggling number of companies with which users have to interact. We have an information economy that relies on the flow of information across multiple contexts. How could you meaningful control all those relationships?

The fundamental problem was always the collection of data, not its control. Europe introduced the GDPR aimed at curbing abuses of customer data. But the legislation misdiagnosed the problems. It should have tackled the collection of data, not its protection once collected.

NOTE: as I reported several years ago, when the GDPR drafting first began the focus was on limiting collection but Big Tech lobbyists and lawyers turned that premise 180 degrees and “control” became the operative word. That has always been Big Tech’s mantra: don’t ask permission. Just do it, and then apologise later if it goes bad. Zuckerberg is the poster boy for that mantra.

Data isn’t harmless, data isn’t abstract when it’s about people. Almost all the data being collected today is about people. It is not data that is being exploited, it’s people that are people exploited. It’s not data in networks being influenced or manipulated, it is us being manipulated.

And that get’s to my main point. “Controlling” data such as age, gender, race, health, and sensitive terms is impossible. It is why these talking heads miss the whole point, especially as regards the Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT is not about security/cyber issues. It is about inference from the stream of data IoT produces. So that AI systems can reconstruct any term they want or need from high-dimensional inputs, plugging all of this information into algorithmic social media analysis to identify, in a split second, sexual preference, political leanings, and income level.

The GDPR was meant to protect people’s privacy, identity, reputation, and autonomy, but it will fail to protect data subjects from the novel risks of inferential analytics.

I thought about that while reading the latest annual report on GDPR enforcement. Another major bump in complaints filed under the bloc’s updated data protection framework, underlining the ongoing appetite EU citizens have for applying their rights, and an uptick in (small) fines. But little to no enforcement of EU data protection rules vis-a-vis big tech. And yet some high profile complaints filed crying out for regulatory action include behavioral ads serviced via real-time bidding programmatic advertising (which the UK data watchdog has admitted for half a year is rampantly unlawful); cookie consent banners (which remain a Swiss Cheese of non-compliance); and adtech platforms cynically forcing consent from users by requiring they agree to being microtargeted with ads to access the (‘free’) service. The thing is GDPR stipulates that consent as a legal basis must be freely given and can’t be bundled with other stuff, so … [shrug]

I spoke to a few regulators at the end of last year at a DPO (data protection officer) event and I was told “these cases are hard, at first blush they seem to be in compliance. And we just aren’t properly staffed”. OK, granted. This is tough stuff. And the “consent” elements and many of the compliance elements are nebulous, much of the connective tissue between sections having been stripped out during negotiations. But, dude: claiming you are “overwhelmed” when you had two years to prepare, budget, and hire before the enforcement date of 25 May 2018 – and time to complain about preparation, budget, and staffing issues beforehand – does not fly. The notion that all of this activity “dropped out of the sky” on the regulation teams as a total surprise doesn’t hold water.

So when control is the “north star” then lawmakers aren’t left with much to work with. It’s not clear that more control and more choices are actually going to help us. What is the end game we’re actually hoping for with control? If data processing is so dangerous that we need these complicated controls, maybe we should just not allow the processing at all? How about that idea? Anybody?

Had regulators really wanted to help they would have stopped forcing complex control burdens on citizens, and made real rules that mandate deletion or forbid collection in the first place for high risk activities. But they could not. They lost control of the narrative. As I noted, as soon as the new GDPR negotiations were in process 4+ years ago the Silicon Valley elves send their army of lawyers and lobbyists to control the narrative to be about “control” burdens on citizens. The regulators had their chance but they got played. Because despite all the sound and fury, the implication of fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy is that individuals would control and manage their own data and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies know it is too late now to impose that structure so they will make sure any new laws that seek to redress any errors work in their favor.

The GDPR came about as a swipe against American Big Tech. Let’s not beat about the bush. The EU wanted to take them down a peg. But the opposite happened. Marketers are spending more of their ad dollars with the biggest players … in particular Facebook and Google .. whom they trust not to run afoul of the GDPR rules and who have the financial firepower to deal with it. So these small marketers can hide in their aprons. And as a presenter said at a legal workshop on the GDPR in Brussels last week “how different countries will enforce the major bits of the regulation is still being determined, probably years out, so any uniform standard for the use of data in digital advertising is unlikely to materialize for quite a number of years.”

The rules have also made it harder for third parties to collect lucrative personal information like location data in Europe to target ads. This gives the tech giants another big advantage: they have direct relationships with consumers that use their products, allowing them to ask for consent directly from a much larger pool of individuals. GDPR has tended to hand power to the big platforms because they have the ability to collect and process the data. It has entrenched the interests of the incumbent, and made it harder for smaller ad-tech companies, who ironically tend to be European. In the longer term, however, it remains to be seen whether the law is going to force a substantial change in Google’s or Facebook’s business model in a way that could loosen their grip on the digital ad market.

Ah, unintended consequences.

California Consumer Privacy Act

The crux of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) is this: if your company buys or sells data on at least 50,000 California residents each year, you have to disclose to those residents what you’re doing with the data, and, they can request you not sell it. Consumers can also request companies bound by the CCPA delete all their personal data. And as The Wall Street Journal reported, websites with third-party tracking are supposed to add a “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” button that if clicked, prohibits the site from sending data about the customer to any third parties, including advertisers.

28th January marked the 14th annual international Data Privacy Day, and ad-tech industry marks the day with a flood of workshops and webinars. Adweek and Ad Age, had multiple events over the three days on and bracketing 28 January, many reflecting on the early impact of the CCPA. This is a mash-up of the webinars I attended.

Public awareness about how personal data is used as a transactional currency is rising, and a survey released that week by FormAssembly (a leading enterprise data collection platform) shows businesses are still grappling with how to move forward. One publisher on an Adweek webinar noted how media companies were lately “operating in the dark” since CCPA – a law affecting companies around the world that possess data on the Golden State’s nearly 40 million residents – came into effect on 1 January 2020 and that the challenges were likely to get steeper. California had made “a pig’s breakfast of this whole thing”. He also noted, as I wrote about last year, that several of the drafters of the legislation had gone to Brussels to meet with GDPR regulators for tips “so it is no surprise it is a mess”.

For ad-tech companies, foundational questions of existence are part of every conversation, but so is trying to navigate some of the unintended consequences of the legislation. A representative from Teads (an ad-tech company that helps publishers improve ad yield) noted that while there has been “low but increasing” adoption of the IAB’s CCPA framework, lots of publishers still had to address their ad stack accordingly.

NOTE: the IAB CCPA Compliance Framework is an attempt to standardize CCPA compliance across the entire ad tech sector. I will discuss this in detail in a few weeks when I publish a draft from my book (see below) on how the ad tech industry works and how it is handling the GDPR and CCPA.

There’s certain types of legwork that has to be done with certain types of integrations. For instance, there are header bidding publishers that need to upgrade because they are not CCPA compliant. It is a significant integration challenge.

NOTE: Header bidding, also known as pre-bidding, is an advanced programmatic technique where publishers offer inventory to multiple ad exchanges at the same time before making calls to their ad servers. The idea is by letting multiple demand sources bid on the same inventory at the same time, publishers increase their yield and make more money. And who doesn’t want more money? These are the folks that determine what you see when you search Google, when you scroll Facebook, or pretty much the ads you see on any web or mobile site. More coming in my ad tech piece.

There has also been some preliminary feedback on CCPA opt-out rates – how often California residents choose the Do Not Sell My Data option on a publisher’s website. They were in the range of 0.3% of total traffic, according to the log data of several tracking vendors. Several law firms on a webinar noted many in the sector are adopting a comparatively relaxed attitude as “full enforcement” by the Office of the Attorney General is not expected until July 2020, although several conceded “or maybe by the fall” because early reviews of the first draft of regulations were “not impressed”. In contrast, further studies demonstrate that the public wants to know exactly which companies have access to their data.

On one webinar just for lawyers, the presenters noted a California bar study showed 85% of California businesses want data privacy regulation at a federal level, while less than half (49%) have a documented means of allowing customers to access and delete their information, a core principle of U.S. privacy statutes, as well as General Data Protection Regulations in the EU. And almost every lawyer said that CCPA guidance from the California AG’s office has been muddled at best: “When CCPA first came out, a lot of companies in the ad-tech ecosystem looked at them and said, ‘I don’t know how to avail consumers of these rights’. So maybe the IAB framework will be adopted since it is a process, better than the proposed regulations I have seen”.

Biggest complaint? Many companies, both consumer-facing and business-to-business, have had to devise whole new processes for handling data, with outfits such as DSPs and supply-side platforms facing fundamental challenges.

Note: a demand-side platform (DSP) is an advertising technology (AdTech to use the right term-of-art) platform that allows advertisers working at brands and ad agencies to buy inventory (aka ad space) on an impression-by-impression basis from publishers via supply-side platforms (SSPs) and ad exchanges via real-time bidding (RTB). I will explain the whole process in my longer piece.

And what we are seeing are proposals that include the potential of using consumer-provided identifiers, such as hashed email addresses obtained by a brand or a publisher, which cannot be reverse-engineered to reveal PII and clearly indicates a users’ privacy preferences. This identifier can then only be accessed by verified third parties which have signed up to a code of conduct and are open to external audit, for the purposes of addressable advertising. It would take companies out of the worry of the CCPA.

The big problem? Smaller ad-tech companies and publishers are in peril given that third-party data has been at the very core of programmatic advertising since its inception. The vastness of the ad-tech and mar-tech ecosystems has made the sector reliant on such technologies, leaving all but the industry’s walled gardens now facing some existential questions – making Facebook, Google and the other tech goliaths more powerful. As always, while a plethora of solutions may benefit from widespread “goodwill”, the real power remains in the hands of those with a consumer-facing offering. You need the approval of the browser makers or you aren’t going anywhere. Given Google’s unilateral decision over cookies’ expiry date (though they are dragging their feet on that), and the sword of Damocles that is privacy legislation, the digital media sector is poised for profound change with Big Tech calling the tune.

And what is making the lawyers salivate? It’s not entirely clear what California is using as its definition of a “sale” of consumer information. Another issue: How is a company going to ensure it is deleting the right customer’s data without collecting more information to verify them? The broad definition of “sale” is a pain point for a lot of companies because it potentially includes sharing information for online advertising. Service provider agreements are another area where companies will have to take a close look at their practices; an agreement with a subcontractor or vendor should carefully spell out how any personal information is used or shared. Which is why the folks at Legaltech are singing: lots of compliance work!!

There are, of course, enormous issues outside the somewhat pedantic issues I have discussed in this brief two-part series. What Neil Postman called “technopoly” may be described as the universal and virtually inescapable rule of our everyday lives by those who make and deploy technology, especially, in this moment, the instruments of digital communication. It is difficult for us to grasp what it’s like to live under technopoly, or how to endure or escape or resist the regime. These questions may best be approached by drawing on a handful of concepts meant to describe a slightly earlier stage of our common culture.

And if you really want to do a deep dive, read the essays by the Polish philosopher Leszek Kołakowski who addresses the distinctions between the “technological core” of culture and the “mythical core” – a distinction he believed is essential to understanding many cultural developments. “Technology” for Kołakowski is something broader than we usually mean by it. It describes a stance toward the world in which we view things around us as objects to be manipulated, or as instruments for manipulating our environment and ourselves. This is not necessarily meant in a negative sense; some things ought to be instruments – the spoon I use to stir my coffee – and some things need to be manipulated – the coffee in need of stirring. Besides tools, the technological core of culture includes also the sciences and most philosophy, as those too are governed by instrumental, analytical forms of reasoning by which we seek some measure of control.

By contrast, the mythical core of culture is that aspect of experience that is not subject to manipulation, because it is prior to our instrumental reasoning about our environment. Throughout human civilization, says Kołakowski, people have participated in myth – they may call it “illumination” or “awakening” or something else – as a way of connecting with “nonempirical unconditioned reality.” It is something we enter into with our full being, and all attempts to describe the experience in terms of desire, will, understanding, or literal meaning are ways of trying to force the mythological core into the technological core by analyzing and rationalizing myth and pressing it into a logical order. This is why the two cores are always in conflict.

So to summarize … and bring this discussion more down-to-earth … the argument is that technopoly is a system that arises within a society that views moral life as an application of rules but that produces people who practice moral life by habits of affection, not by rules. Think of Silicon Valley social engineers who have created and capitalized upon Twitter outrage mobs. Put another way, technopoly arises from the technological core of society but produces people who are driven and formed by the mythical core.

It’s why data governance and the new frontiers of resistance are so difficult. Anita Gurumurthy, who founded “IT for Change” which works at the intersection of development and digital technologies and produces a huge volume of work on information society theory, puts it this way:

Four centuries after the East India Company set the trend for corporate resource extraction, most of the world is now in the grip of unbridled corporate power. But corporate power is on the cusp of achieving “quantum supremacy” and social movements in the digital age need to understand this in order to shift gears in their struggles. The quantum shift here comes from “network-data” power; the ingredients that make up capitalism’s digital age recipe.

Her point is the same as mine: contemporary capitalism is characterized by the accumulation of data-as-capital. Big Tech uses the “platform” business model. This model provides a framework for interactions in the marketplace by connecting what Gurumurthy calls “its many nodes: consumers, advertisers, service providers, producers, suppliers and even objects” that comprise the platform ecosystem, constantly harvesting their data and using algorithms to optimize interactions among them as a means to maximize profit.

Note: the platform model emerged as a business proposition in the early 2000s when internet companies offering digital communication services began extracting user data from networked social interactions to generate valuable information for targeted advertising. It is estimated that by 2025, over 30 percent of global economic activity will be mediated by platform companies, an indication of the growing “platformization” of the real economy. In every economic sector, from agriculture to predictive manufacturing, retail commerce and even paid care work, the platform model is now an essential infrastructural layer.

And that is the objective point of government regulators: control over data-based intelligence gives platform owners a unique vantage point – the power to shape the nature of interactions among member nodes. Practices such as Amazon’s segmenting and hyper-targeting of consumers through price manipulation, Uber’s panoptic disciplining of its partner drivers, and TripAdvisor’s popularity ranking algorithm of listed properties, restaurants and hotels are all examples of how such platforms mediate economic transactions. The accumulation of data that feeds algorithmic optimization enables more intensified data extraction, in a self-propelling cycle that culminates in the platform’s totalizing control of entire economic ecosystems.

Amazon for instance, is no longer an online book store, and was perhaps never intended to be. With intimate knowledge about how the market works, Amazon is a market leader in anticipatory logistics and business analytics, providing both fulfillment and on-demand cloud-based computing services to third parties. Not only has it displaced traditional container-freight stations in port cities, it has begun to look increasingly like a shipping company. The dynamics of an intelligence economy have led to large swathes of economic activity being controlled by a handful of platform monopolies.

All government privacy regulators/enforcers, at least those in the West, are facing a losing battle. Under the rubric of “ubiquitous computing,” “smart dust,” and the “Internet of Things,” computers are melting into the fabric of everyday life. Light bulbs, toasters, even toothbrushes are being chipped. You can summon Alexa almost anywhere. And as life becomes computerized, computers become lifelike. Modern hardware and software have gotten so complicated that they resemble the organic: messy, unpredictable, inscrutable. In machine learning, engineers forswear any detailed understanding of what goes on inside.

And worse, government is even complicit. Yes, the tsunami of news coverage has shown us how dating sites save your conversations, how automatic location services on your phone unwittingly make you a moving, pinpointed target, or how fraught developments in facial recognition technology could spell the end of public anonymity. But law enforcement agencies across the U.S., the UK, and Continental Europe have been purchasing apps which pair images – security tape footage, a photobomb – with a database of millions of pictures scraped from sites such as Facebook, Instagram, Venmo, YouTube, etc. In an episode of the New York Times long-running investigation into all there was a discussion that demonstrated several of the apps being used in the U.S. that, if fallen into the wrong hands, could potentially not only identify activists at a protest or an attractive stranger on the subway, but reveal not just their names but where they lived, what they did and whom they knew.

And us? Where to begin. We seem to be living at a time when a series of technologies and seemingly innocuous shares have amassed into a sludge pile, drowning out public anonymity or individual privacy. It is a soup of surveillance. And not our fault, really. Since we humans are social animals, and the internet is a communications network, it is not surprising we adopted it so quickly once services such as email and web browsers had made it accessible to non-techies. The tech just “glided” us there. Why? Well, as my regular readers have heard ad nauseam from me it runs like this:

Digital is different from earlier general-purpose technologies in a number of significant ways. It has zero marginal costs, which means that once you have made the investment to create something it costs almost nothing to replicate it a billion times. It is subject to very powerful network effects – which mean that if your product becomes sufficiently popular then it becomes, effectively, impregnable. The original design axioms of the internet – no central ownership or control, and indifference to what it was used for so long as users conformed to its technical protocols – created an environment for what became known as “permissionless innovation”. And because every networked device had to be identified and logged, it was also a giant surveillance machine. As the security guru Bruce Schneier says all the time: “Surveillance is the business model of the internet.”

But because providing those services involved expense – on servers, bandwidth, tech support, etc – people had to pay for them. (It may seem incredible now, but once upon a time having an email account cost money.) Then newspaper and magazine publishers began putting content on to web servers that could be freely accessed, and in 1996 Hotmail was launched (symbolically, on 4 July, Independence Day) and then … well, you know the history.

Regulation? As I have discussed in this series, our institutions of governance and law and commerce mostly originated during the 18th century Enlightenment and are simply no longer suitable for this connected and complex world. But listen: politicians aren’t stupid. We would really miss these services if they were one day to disappear, and this may be one reason why many politicians tip-toe round tech companies’ monopoly power. And the fact that the services are free at the point of use has completely undermined conventional anti-trust thinking for decades: how do you prosecute a monopoly that is not price-gouging its users? Yes, yes, yes. I know. In the case of social media, users are not customers, they are the product. Monopoly may well be extorting its actual customers – advertisers – but nobody seems to have inquired too deeply into that until recently. More on that in another post-to-come.

I’ll leave it there for the moment. I will return to all of these points in my greater challenge, finishing my book “The death of data privacy, and the birth of surveillance capitalism: how we got here”. Many of you received the very preliminary draft of the introductory chapter and I received a steam of suggested edits and comments for which I am very grateful.

In sum: in this digital age, we struggle (delusionally) to defend liberal values and concepts we developed in an analogue era. I will address the death of privacy and the infantile disorder of imagining there is data privacy – or any privacy – anymore.

Much more to come.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

POSTSCRIPT: FOUNDATIONAL TEXTS

As indicated, writing something like this 2-part series and my The Death of Data Privacy work-in-progress, requires a very extensive “consumption” regimen. For the latter, 170+ books plus 102+ white papers/briefs/articles plus 40+ conversations/interviews (at last count).

But you need to start with some foundational texts. For this series I used the following books and supplemental material:

• To understand the 200 year evolution of high-risk investing in America, by the venture capital community and the government, and the deep context for understanding the sources of a digital revolution that is now redefining economic, political, social, and cultural life around the world:

“Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970” (2005) -Christophe Lécuyer

“VC: An American History” (2019)- Tom Nicholas

“The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America” (2019) – Margaret O’Mara

• To comprehend the physical realities of the Internet, the Web and the digital architecture around us:

“Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet” (2013) – Andrew Blum

“Digital Design and Computer Architecture” (2015) – Sarah Harris and David Harris

“Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft, and the Battle for the Internet” (2013) – Charles Arthur

These books were supplemented by myriad articles plus numerous conversations at events like the International Cyber Security Forum and the Mobile World Congress.

• To understand the advertising industry and advertising technology (adtech) and the range of software and tools that brands and agencies use to strategize, set up, and manage their digital advertising activities:

“Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy” (2016) – Geoffrey G. Parker

“Platform Capitalism” (2017) – Nick Srnicek

“Ways of Seeing” (2008) – John Berger

These books were supplemented by myriad articles plus numerous conversations at events like Cannes Lions. That event is the advertising industry’s mega annual conference/trade show. I call it “The Conference of the World’s Attention Merchants” because over the last decade, the festival has evolved to include not only more brand clients but also, due to media fragmentation which has led to the change of some and the birth of others, an expansion into tech companies, social media platforms, consultancies, entertainment and media companies — essentially the entire attention ecosystem.

I also want to add numerous Adweek and Ade Age workshops and webinars.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Some claim the world is gradually becoming united, that it will grow into a brotherly community as distances shrink and ideas are transmitted through the air. Alas, you must not believe that men can be united in this way. To consider freedom as directly dependent on the number of man’s requirements and the extent of their immediate satisfaction shows a twisted understanding of human nature, for such an interpretation only breeds in men a multitude of senseless, stupid desires and habits and endless preposterous inventions. People are more and more moved by envy now, by the desire to satisfy their material greed, and by vanity.

– Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (1880)