15 December 2019 (Paris, France) – As my family dashed around town for their “let’s-buy-everything-in-the-stores” holiday tradition (and mind you strikes have closed the Paris Metro system except for Line 1 so they are getting their exercise), I stayed ensconced in my study pouring through the tsunami of stats produced over the weekend on the British election, much of it by British mates Ian Warren (independent analyst) and John Murdoch (FT) who have programs that can analyse just about every data point coming out of the UK Electoral Commission.

Me? It seems the best way to deal with a party leader you don’t like is to vote for the other guy whose political ethos is fraud. It reinforced the narrative that when the quality of life gets worse, pique-driven resentment will again be directed at others. So I’m not sure if the UK is heading to a utopian dystopia – or a dystopian utopia.

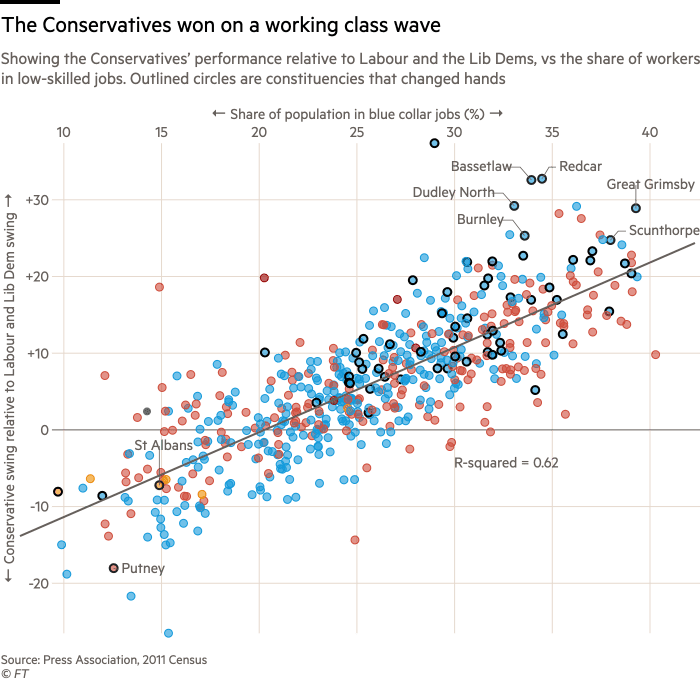

But the electoral numbers also reinforce another narrative that a few (not many) UK political pundits addressed before the election: that the share of workers in low-skilled jobs were going to be a bigger predictor of swing than either the Brexit vote or graduates. That is illustrated by the graph at the top of this page. Just three points (of many; I cannot fit them all in):

• In seats with high shares of people in low-skilled jobs, the Conservative vote share increased by an average of six percentage points and the Labour share fell by 14 points.

• In seats with the lowest share of low-skilled jobs, the Tory vote share fell by four points and Labour’s fell by seven.

• The swing of working class areas from Labour to Conservative had the strongest statistical association of any explored by the FT analytics team and the Politico team

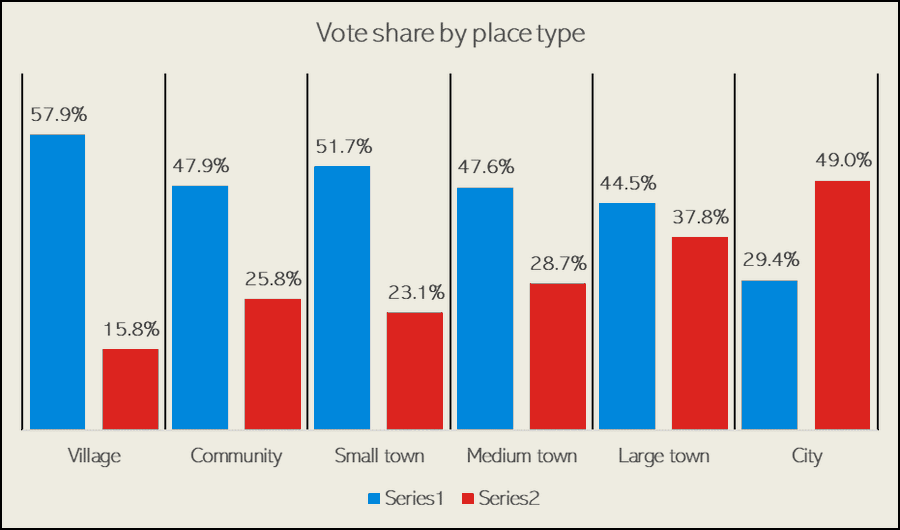

More telling was this chart which Ian sent out:

That city-dweller/non-city dweller divide is extensively discussed in Capitalism without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake, a book I have cited numerous times in past posts. It is the first comprehensive account of the growing dominance of the intangible economy. As I noted in one of those posts:

Early in the twenty-first century, a quiet revolution occurred. For the first time, the major developed economies began to invest more in intangible assets, like design, branding, R&D, and software, than in tangible assets, like machinery, buildings, and computers. For all sorts of businesses, from tech firms and pharma companies to coffee shops and gyms, the ability to deploy assets that one can neither see nor touch is increasingly the main source of long-term success.

But this is not just a familiar story of the so-called new economy. Capitalism without Capital shows that the growing importance of intangible assets has also played a role in some of the big economic changes of the last decade. The rise of intangible investment is, Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake argue, an underappreciated cause of phenomena from economic inequality to stagnating productivity.

Higher skilled jobs are clustering in small numbers of cities. We’ve seen the pattern play out in the U.S., Turkey, Hungary and many other places. It is part of the ongoing resurgence of place in our political economies. One key driver is our shift to an intangible economy whose patterns and processes strongly favour local agglomeration into big cities. This is a major trend of the exponential age.

For example, tech jobs and the wealth they generate are becomingly increasingly concentrated in the US. Since 2005, just five metro areas have accounted for 90 per cent of all US growth in innovation sector jobs. The tech industry is far more driven by network effects than other industries; where manufacturing requires being close to sources of raw materials, tech requires being close to people who are sources of ideas and expertise, incentivising large tech companies to cluster together and creating a ‘winner-takes-most’ dynamic.

The result: wealth and productivity are becoming even more concentrated in fewer, primarily coastal cities. One-third of the nation’s innovation jobs resides in just 16 counties; half are concentrated in 41 counties. These jobs are high-paying and contribute to overall faster wage growth in the areas they’re located, than in areas with fewer innovation jobs. They also result in a lot of secondary work — but they are low-skilled jobs created to help serve those workers.

And a warning to the Democrats

Washington (CNN)The Labour Party’s wipeout in Britain’s election spelled out an undeniable warning to Democrats over the potential dangers of tracking too far to the left of more moderate national electorates. But it also highlighted a more profound parallel in the often synergistic US and UK politics that potentially poses longer-term threats to progressive parties: culturally and politically, they have lost touch with their heartland working-class voters — the very people they were set up to represent. The most significant warning for Democrats from Jeremy Corbyn’s disaster may be that when a party gets consumed by its own ideological debate, it risks losing sight of subtle changes in its own base.

The bigger picture

I am sufficiently ignorant about the UK to say I do not know if the U.K. is heading somewhere very dark. The U.S. is certainly going to the Dark Side. The more sentimental believers in the “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom focus on synchronous developments in American and British politics during the past century. The Second World War, in this telling, was won by a pair of anti-fascists whose alliance and friendship made the world safe for democracy. Even more jaundiced observers cannot help but notice commonalities. In the nineteen-fifties, two moderately conservative regimes turned their countries slightly to the right, while establishing a decades-long, bipartisan commitment to the welfare state. A generation later, the conservative revolution arrived in both countries, with Margaret Thatcher triumphing over an enfeebled Labour government, in 1979, and Ronald Reagan routing Jimmy Carter, in 1980. In the nineteen-nineties, two slick center-left politicians, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, transformed their parties; just as the fifties conservatives had made peace with a social safety net, Democrats and Labourites made it clear that they welcomed the role of free markets and financial capital.

And then, in the summer of 2016, the U.K. voted to leave the European Union. Months later, the U.S. elected Donald Trump, a man who actually referred to himself as “Mr. Brexit” several times that summer. These twin “populist” explosions have been the central drama in each country ever since, feeding the news cycle on both sides of the Atlantic with the same mixture of apprehension and disbelief.

During the last three years I have probably read more than my fair share of books and articles exploring the United Kingdom’s problematic relationships with Europe and the Commonwealth.

NOTE: I highly recommend Fintan O’Toole’s new book, “The Politics of Pain: Postwar England and the Rise of Nationalism” .

I think the proper emphasis on this is the shift in the country’s global position during the mid-twentieth century – which resulted from its loss of empire and its struggle to establish a new identity for itself – as a reason for its current populist predicament. Dean Acheson’s famous remark, in 1962, that “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role” suggested that striving to become a social democracy within Europe would somehow have been an insufficiently glorious ambition for an erstwhile world power. I believe that the U.K.’s problems with Europe are also due to the demise of another feature of postwar British politics: the welfare state. Although the days of the sun never setting on the British Empire were over, the UK was nevertheless able to offer its citizens a social safety net that it hoped would be the envy of the world.

The conservative political revolution of the nineteen-eighties, in both the U.K. and the U.S., began to dismantle those social protections. As a consequence of a generation of deregulation, the fetishization of the market, and cuts to service provisions, average people feel exposed to the cold winds of change on their home turf. Their response was to hunker down, look after themselves, and find others to blame. The jury is still out on what its future relationship with Europe will look like.

I have not given enough attention to this demographic shift in political economies. It’s a short post. I’ll write more in the coming year. So I’ll conclude with this. More than a decade ago, Thomas Friedman argued that the world was flat: advanced communications technologies, in fact advanced technologies in every field, and globalisation would create a perfect marketplace, flattening the economic playing field for both business and workers. Friedman emphasised the force of technology as the key driver of this flattening world.

He was wrong. Far from flattening the world, the technologies he referred to have fractalized it. In the UK, they have certainly contributed to the rise of a backward-looking, imperialistic and xenophobic political force. As long as this sort of fearful individuality is ascendant, maybe the U.K. is heading somewhere very dark indeed.