Time to hang up my social media shoes for a bit

29 August 2019 (Serifos, Greece) – When I joined Twitter and Linkedin about 12 years ago (the first one for the firehose of news, the second for more thoughtful chats) I wanted, more than anything, to communicate directly with all the sources I depended on for my media work. And to get feedback on pieces I wrote. Charles Arthur, the freelance journalist and former technology editor at The Guardian newspaper (author of the monumental Digital Wars: Apple, Google, Microsoft and the Battle for the Internet) had noted:

Screenwriters get to go to meetings and hang out on set, playwrights can watch an audience respond to their words up close and in real time — but writing is a lonely business that involves spending many months in isolation crafting something that will be consumed privately and elsewhere by strangers.

Since being on both Twitter and Linkedin I’ve had conversations with scores of people (many strangers) who have suggested research avenues I had not considered. I also got a sense of what my posts were doing out there in the world (some crap, some good) — impossible only 12 years ago. And I have returned the favor – able to sing the praises of books, films, plays and exhibitions I’ve enjoyed (keeping it honest). And I’ve made long-lasting friends on Twitter and Linkedin, some of whom have become friends in the physical world.

And I have seen brilliant pieces on both networks, making me more knowledgeable about politics in general – and perhaps a little too knowledgeable about American, British and Italian politics in particular. Both have been a fertile source of long-form journalism, which I download to Pocket and read offline. I have had a ringside seat to watch investigative journalists at their best … their (somewhat futile) fight for democracy and the rule of law, the battle over the climate, etc. All that plus many marvellous posts on art and culture, and wonderful science videos. Ok, I have also enjoyed the videos of stupid drunk men failing to leapfrog barbecues. Full admission.

Yes, I am painfully aware – how could anyone not be? – of the misogyny, the nastiness, the deliberate trolling and the howling lack of nuance; aware, too, of the pointlessness of responding by shouting loudly back into the Twitterverse. I am sure the internet is damaging the brain structures of the young but I need to read more about that. And I know my ability to focus on one task for a sustained period has deteriorated since I became addicted to that repeated swipe from one vaguely interesting thing to what promises to be, but rarely is, a slightly more interesting thing.

And you do end up in this “sameness” group, getting this positive feedback and so you are cushioned by a kind of cocoon that your milieu forms around you. You get an impression that the real noises of life reach you, but muted, all connection with reality strained out.

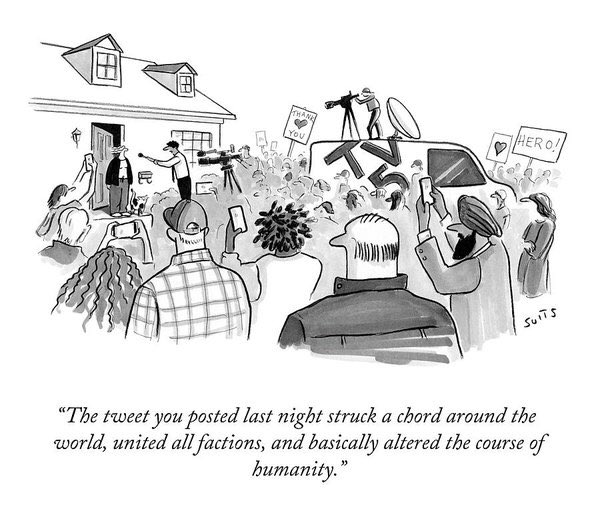

Then all of a sudden every Tweet and Linkedin post began to feel like a peep of steam through my whistle – “Listen to me! Listen to me!” – which reduced the boiler pressure I needed to focus on serious writing. What really persuaded me to retreat from Twitter (and Linkedin) for awhile is something less distinct (but more sinisterly pervasive) and I am sure I am not alone: a growing sense that it was detrimentally affecting the way I both looked at and thought about the world around me, even when I was away from a screen. When reading a novel, watching a TV program or visiting an exhibition, a part of my mind would be constantly alert for, and quietly fashioning, “Tweet-able” and “Linkedin-able” material – highlighting the more succinctly packageable aspects of what was in front of me and simplifying the more complex aspects.

Yep. A desperate desire to concoct a mildly clever bon mot, a thought to blow away the Twitterverse.

I know many believe it is a lazy trope to blame a string of global ills, from Donald Trump to revenge porn to the growth of male anorexia, on social media as a whole, as if it were one monolithic, undifferentiated phenomenon. But hear me out …

There’s a passage in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises which I love to quote in which a character named Mike is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he answers. “Gradually, then suddenly.”

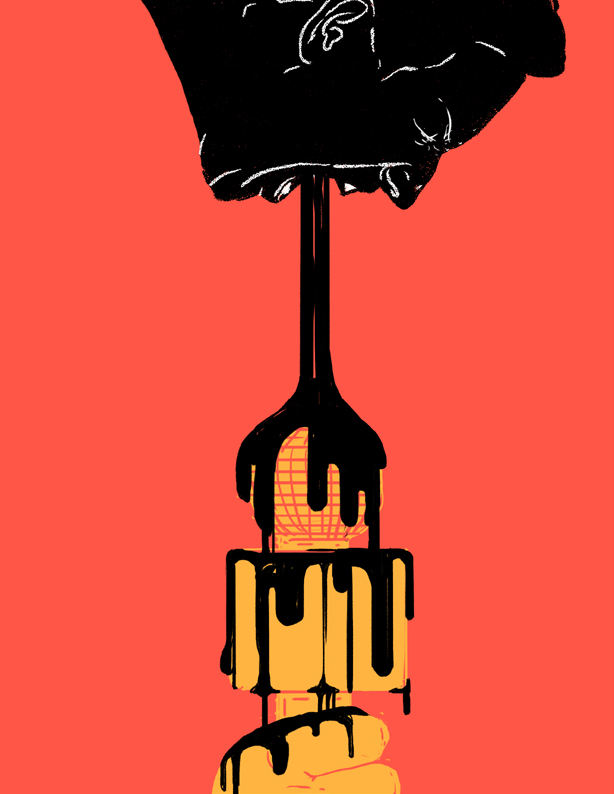

Technological change happens much the same way. As does political change. Small changes accumulate, and suddenly the world is a different place. We’ve all tracked (and some of us have been involved with) “gradually, then suddenly” movements: the World Wide Web, open source software, big data, cloud computing, sensors and ubiquitous computing, and now the pervasive effects of AI and algorithmic systems on society and the economy.

But social media technology has transformed politics and society irrevocably, in a dystopian way, that we are only now slowly grasping. Our civil institutions were founded upon an assumption that people would be able to agree on what reality is, agree on facts, and that they would then make rational, good-faith decisions based on that. They might disagree as to how to interpret those facts or what their political philosophy was, but it was all founded on a shared understanding of reality. And that’s now been dissolved out from under us, and we don’t have a mechanism to address that problem.

The Internet expands the horizon of every utterance or expressive act to a potentially planetary level. This makes it impossible to imagine a purely local context or public for anything that anyone creates today. It also de-centres the idea of the global from any privileged location. No place is any more or less the centre of the world than any other anymore. As people who once sensed that they inhabited the intellectual margins of the contemporary world simply because of the nature of geo-political arrangements, we know that nothing can be quite as debilitating as the constant production of proof of one’s significance. The Internet has changed this one fact comprehensively. The significance, worth or import of one’s statements is no longer automatically tied to the physical facts of one’s location along a still unequal geo-political map.

And so I’ve been trying to work out why social media churn is so exhausting and debilitating. Clearly, churn has a number of effects on individuals: burnout, anger, desolation, suicide, pivots, failures, perpetual beta. Oh, and we can talk about all the rest: hypercompetition, digital disruption, yada yada yada.

I subscribe to the view of Peter Stannack … he is CEO of Prebbler Technologies, a self-described “Punk AI Proponent, Machine Intelligence Integrator” but I’d also add polymath. We have been chatting for years and you’ll hear more about him after my “vacation”. Peter told me this in our last chat:

My current pet theory for the transformation of business and sociality is a result of wave effects from the constant moral panics which wash across social media. These can be small or large. Political or business. Public or personal. As Couldry, Livingstone, and Markham observed in 2007 during their study of media consumption and public engagement, and you’ll see it is spot on to today:

“Attracting and sustaining citizens’ attention is a central challenge in modern democracies and a prerequisite for most political or civic action, from opinion formation or public discussion to voting or direct participation in democratic institutions. But how such attention is managed raises important questions, particularly since this attention is likely to be uneven, and perhaps unequally distributed. This complexity is compounded by the contestability of the public/private boundary itself”

I think social sound has been turned into white noise, and that white noise has become the new social order. The acceleration and corruption of cyberspace has broken the rhythm of our mental time to the point that we simply no longer know what’s relevant, what’s irrelevant in our surrounding environment. And what we do is call it “chaos”.

We throw around the word “chaos” all the time. But what are we really speaking about when we talk about chaos? It’s fairly simple. Chaos stands for an environment that is simply too complex to be decoded by the available explanatory frames we normally work in. The environment literally and flexes and circulates too quickly for our minds to elaborate. The notion of chaos is that it is simply a complexity dancing too fast for our brains to decipher. Chaos takes a special place today in the sphere of social sciences as the order of modern civilization is simply falling apart.

And that corruption of the information ecosystem and the global information dystopia is not just a multiplier that has shattered the pillars of modern democratic self-government. Yes, the audacious use of misinformation to shape public opinion at home and abroad allows countries like Iran and Russia to punch well above their hard and soft power weight classes in shaping world events. And worse: Iran has put into practice lessons in hybrid warfare that Moscow field-tested on the battlefields of Ukraine and later unleashed against Western democracies. Western leaders have not a clue the horrors that await them in 2020.

My issue is that it has all led to climate change denialism that can be fairly characterized as cyber-enabled information warfare against the reality of large-scale anthropogenically-induced climate change.

This summer my big reads have been on climate eschatology, that a warming Earth will radically change life as we know it, we can’t change it, so let’s just face the adjustments we’ll need to make because we are doomed. Yes, a pessimistic view but I am also re-reading the work of Rachel Carson (there is a monster of a new compendium out with all her writings) and while everybody knows “Silent Spring”, it’s her books and articles about the sea … exploring the whole of ocean life from the shores to the depths … that deserve more attention. She was incredibly prescient about what was happening to the seas due to exploitation, and even more so about what she perceived was the growing “government assault on science and nature”.

Because social media networks are optimally designed to stimulate what cognitive scientists call “System 1 thinking” – emotional, reflexive, immediate — and they rapidly transmit content among like-minded individuals, creating the ideal conditions for public polarization and divisiveness to occur. It allows multiple narratives to rapidly emerge around complex events; citizens splinter into their own informational universes and are unable to agree on an underlying reality.

In this networked culture we have seen the transformation in the relationship to power and information. Shit storms occur for many reasons. They arise in a culture where respect is lacking and indiscretion prevails. The shit storm represents an authentic phenomenon of digital communications. Sovereign is he who can command the shit storms of the net.

When I was trolling one of my bookshop haunts in Athens this summer I came across a collection of essays written in 1938 by none other than Adolf Hitler. One of them was titled “The Manual of German Radio”. In that essay Hitler says “without the loudspeaker we would never have won throughout Germany”. Now power emerges from a storm of an audible voices. Power no longer needs eavesdropping or censoring. On the contrary, it stimulates expression and draws rules of control from the very statistical elaboration of data emerging from the noise of the world. Sovereign is he who can command the shit storms of the net.

If you pull far enough back from the day to day debate over technology’s impact on society – far enough that Facebook’s destabilization of democracy, Amazon’s conquering of capitalism, and Google’s domination of our data flows start to blend into one broader, more cohesive picture – what does that picture communicate about the state of humanity today? We have clothed ourselves in newly discovered data, we have yoked ourselves to new algorithmic harnesses, and we are waking to the human costs of this new practice. Who are we becoming?

So it is no surprise that political and corporate leaders are themselves subject to (and abusers of) these conflicting narratives and may even be active and influential participants in one or another of them. Especially in climate change, which has been my summer focus. When Greta Thunberg and the Extinction Rebellion are tagged “enemies of the working class”, that they will hurt the profits of corporations and fossil fuel companies and therefore the poor, it is visceral, emotional. How do you counter with “thoughtful” analysis, that climate change is actually impacting some of the poorest people in the world living in the global south?

What’s lost? Not that Thunberg is a “tool” of climate changers. The thought that should resonate (but is lost) is that as a child she’s observing that there’s a gigantic, possibly existential problem; that all the science says so. And so she wants the adults – the experts, even? – to sort it out, instead of denying it. But she is drowned out and abused.

We are way beyond arguing about the science here, and fast moving beyond politics too, at least in the conventional sense of debating how far and how fast it’s reasonable to move in a democracy, or whether the moral absolutists of movements such as Extinction Rebellion have thought hard enough about the impact on other people’s livelihoods. The nihilists win out.

Our science is like a store filled with the most subtle intellectual devices for solving the most complex problems, and yet we are almost incapable of applying the elementary principles of rational thought. And in most cases, we do not take the time. The Internet … for most of us … changes the way we think. It puts us all in the present tense. It’s as if our cognitive resources are shifted from our hard drive to our RAM. That which is happening right now is valued, and everything in the past or future becomes less relevant. The Internet pushes us all toward the immediate. The now. Every inquiry is to be answered right away, and every fact or idea is only as fresh as the time it takes to refresh a page. And as a result … speaking for myself … the Internet has made me mean. Resentful. Short-fused. Reactionary.

So this escape of mine from the grid, from the Matrix, is in keeping with advice given to me long, long, long ago by my first guru, Dominique Senequier (she now heads Axa Private Equity in France), who told me the trick to happiness and personal success is to be committed to all aspects of your life, and find time to disconnect every once and awhile. Otherwise “we are like fish who do not know they swim in water, and are seldom aware of the atmosphere of the times through which they move”.

The breathtaking advance of scientific discovery and technology has the unknown on the run. Not so long ago, the Creation was 8,000 years old and Heaven hovered a few thousand miles above our heads. Now Earth is 4.5 billion years old and the observable Universe spans 92 billion light years. But I think as we are hurled headlong into this frenetic pace we suffer from illusions of understanding, a false sense of comprehension, failing to see the looming chasm between what our brain knows and what our mind is capable of accessing. It’s a problem, of course. Science has spawned a proliferation of technology that has dramatically infiltrated all aspects of modern life. In many ways the world is becoming so dynamic and complex that technological capabilities are overwhelming human capabilities to optimally interact with and leverage those technologies.

This past year I felt my life lived in pieces: shards, ostraca, palimpsests, sometimes crumbling codices with missing pages. A barrage of news clips from CNN, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, and [“name-your-social-media-blaster”]. We have created an environment which rewards simplicity and shortness, which punishes complexity and depth. Yes, we may never know more than part, as “through a glass darkly”, and all knowledge comes to us in pieces, but we do owe ourselves “big think” time.

This summer I decided to go back to “the narrative”. I noticed that I was digesting my knowledge as a patchwork drawn from a wider range of sources than I used to. I noticed, too, that I was less inclined to look for joined-up finished narratives and more inclined to make my own collage from what I can find. I noticed that I read books more cursorily, scanning them in the same way that I scan the Net and “bookmarking” them.

And I noticed that I corresponded with more people but at less depth. I noticed that it is possible to have intimate relationships that exist only on the Net that have little or no physical component.

And I noticed that the idea of “expert” has changed. An expert used to be “somebody with access to special information”. Now, since so much information is equally available to everyone, the idea of “expert” becomes “somebody with a better way of interpreting”. Judgement has replaced access.

And yes, yes, yes. There has been an enormous benefit. Social media has given me information from so many disparate people and systems (often invisibly), steering my behavior into all kinds of paths, which I can only hope are beneficial. It has increased the number of people whose thoughts are in my head. Because of the Internet, memes and calculations of more people (and/or computers) passes through us. Good or bad, this new level of connectedness sometimes gives me the feeling that many times I have been picked up a few feet over ground … and realized I am part of an ant hill.

To be an informed citizen is a daunting task. To try and understand the digital technologies associated with Silicon Valley — social media platforms, big data, mobile technology and artificial intelligence that are increasingly dominating economic, political and social life – has been an even more daunting task that brought me to interview scores of advertising mavens, data scientists, data engineers, psychologists, etc. Plus reading reams of white papers and books tracking the evolving thinking and development of this technology. I needed to dust off some classic tomes that have been sitting in my library for years, from authors such as James Beniger, Marshall McLuhan and Alvin Toffler … all of them so prescient in where technology would lead us, their predictions spot on to where we are today.

It’s why I make sure my media crew and I are out there attending an esoteric collection of conferences, doing our own research. I have also felt my role was to “DJ the internet”, to do deep dives into all subjects and to deliver to my readers daily mixes of fresh ideas. My team and I search each day to find different angles and points of view that lead to deeper understanding. Industry insights, stories from the “dark side”, etc.

So now … silence. And thought. a separation from the the global hive mind that has emerged with sites like Twitter and Facebook and Linkedin.

So I am going to shut up and walk the beach, and climb the rocks near my house, and enjoy my hammock – and think. I am going to dip into my library of books (it just peaked at 18,600 volumes) and watch films with a new level of attention, tucking away images and ideas not in order to “Tweet” but to store in that great mental lumber room in my mind which I sort through every so often in search of material. I have rediscovered my use of notebooks and the joy of making lists and diagrams and flow-charts (with four different colored pens!!) and some (pathetic) illustrations.

Yes, yes. I know. There are hundreds of great minds who have never been near social media. And the invention of the newspaper didn’t fundamentally alter the ability of human beings to be as variously stupid, creative, cowardly, hilarious, angry and kind as they ever were. But I think our Star Trek-style thought transporters will change us, has changed us.

I’m not judging or being judged. I just need the silence and space for thoughts to unfurl in whatever direction, undisturbed by electronics. I want to use those notebooks … automatic error-correction is never the default … and go over and over the same material, adjusting, correcting, copying out, underlining, coloring . . . the way that tactile, childish and seemingly pointless activities always see to force you to examine things in every detail, from every available point of view.

My wife reminded me our parents used to warn us 50/60 years ago that if we sat too close to the television we would damage our eyes. They never explained why: doubtless some kind of rays that only became safe once they reached the sofa where you were sitting. Maybe I’ve turned into my parents and I am getting old and inelastic and can’t effectively adapt (regulate?) to these new fangled modes of communication, that I cannot place boundaries between the private and the public.

Or maybe I just want to get away from the noise for awhile, to listen more clearly to my own voice and remember how much I really do prefer quiet seaside walks to noisy city streets, both literally and metaphorically.

Those who need to get in touch with me know how. Right now I am off to try and save some sea turtles.