8 June 2019 (from some rock in the middle of the Mediterranean) – It’s been a brutal week. We just observed the 75th anniversary of D-Day, the June 6, 1944 event that was history’s greatest amphibious invasion … 7,000 vessels and 11,500 airplanes supporting 156,000 Allied soldiers who crossed from Britain to five beaches in France. And as the number of surviving veterans from that event dwindle, the old pillars of trans-Atlantic certainty have begun to tremble, perhaps nearing collapse.

And we’ve entered the 30th anniversary of “the two 1989s”. The year 1989 is synonymous with the fall of the Berlin Wall. But five months before the wall came down … as we observed earlier this week … the Chinese military entered Tiananmen Square and crushed the pro-democracy movement.

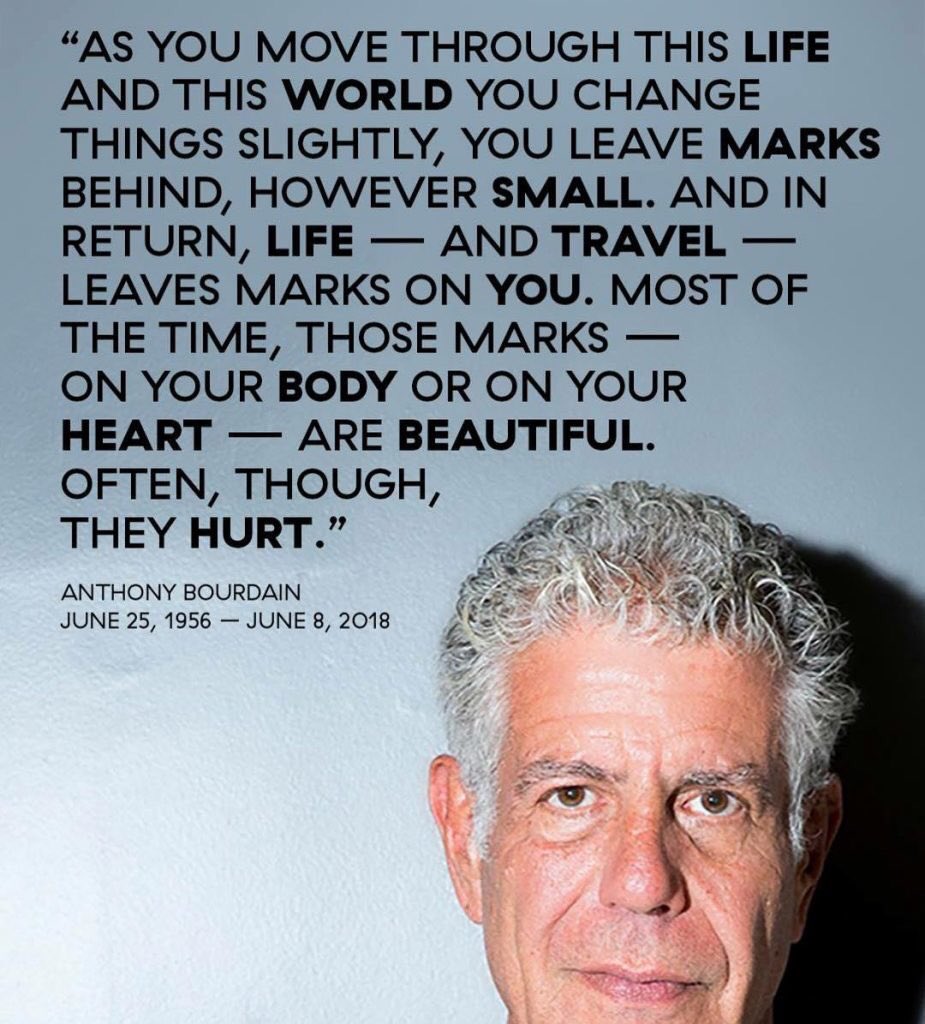

I can never be sanguine about any of this stuff but I try to make it personal. So today I observe that it has been one year since we lost Anthony Bourdain. And to me, he was important. I never met Anthony Bourdain although I did eat in his NYC restaurant a number of times. I read most of his books. And I saw him a lot on television.

He was important to me because he was a humanist. I wrote a tribute to him last year. He was someone who spent his time attempting to show us that not only are the people on this planet a lot alike, but the parts of us that are different are wonderful too. He should have been important to a lot of us.

When we look at a mountain we see one face of it, and even if we wake up and gaze at that same mountain every single morning of our lives, we do not see its wholeness. We can hike it, fly over it, traverse its circumference a thousand times and still we won’t see its entirety, every layer, every element, every atom.

To know a mountain, or a person, is to see a whole being in its fullness at all times in all seasons — every mood, every moment. If there was a God (there is not), that is what God would see.

But we are not gods, and so our view, no matter how vast, is always partial.

I admire Anthony Bourdain as much as anyone who never met the man could. I say “admire” in the present tense rather than the past because I don’t see a future in which I will not admire him, and I certainly don’t live in a present moment in which I have anything less than absolute respect for the man, be he here, elsewhere, or nowhere.

For instance, In 2001, the Taliban blew up a pair of giant medieval-era statues of the Buddha in the Bamyan valley in the Hazarajat region of Afghanistan, northwest of Kabul. At 115 and 175 feet tall, carved out of a cliff, the Buddhas adorned part of the Silk Road that runs from China through the Hindu Kush mountain region onward to parts west. For centuries, they inspired awe. How could humans with such limited means build towering monuments like these? And then they were gone, profanely smote to smithereens in a giant “fuck you” to cultural diversity, to real history, to heritage, and to international presence.

I admire them still, though they are dust.

You don’t forget what emerges from the earth, or what returns to it.

I cannot possibly understand Bourdain’s leaving. His reasons were his own. And I understand when people are shocked that a wealthy person, a successful person, a beloved person would kill himself. Or herself. When someone has the external trappings of success, we may find ourselves astonished and even pissed that he’d choose to shuffle off this mortal coil. I think this is because we imagine that if we had the TV shows, the wealth, the fame, the books, the adulation, the acclaim, that everything would be all right. It’s what we are taught.

And it’s bullshit. We’ll never be able to crawl into that mind.

But he has given us all the words we’ll ever have from him, and he’s given us plenty, and I am grateful for them. As a writer, I was simply knocked over by his brilliance as a memoirist. Personal nonfiction writing can give the illusion that you know its author quite well, that he is your friend, that he/she really understands you. It’s only an illusion, and when it works, it’s because the writing is good.

And if you spent an hour reading his words, watching his TV show or listening to him on the radio and you didn’t want to eat with him, drink with him or just talk with him, then we have decidedly different taste in humans. He was a real one. We’re lucky we had him for as long as we did.

Because we need humanists right now. We need people to show us the best parts of ourselves. And he was important to me because he was a self-admitted flawed humanist. To me he was “Mister Rogers”. Well, ok, if Mister Rogers had spent his 20s doing heroin and banging waitresses in the walk-in freezer. Or as AA Gill said in a memorable blurb from his review of Bourdain’s seminal first book Kitchen Confidential, he was “Elizabeth David … written by Quentin Tarantino”. (Elizabeth David was a British cookery writer. In the mid-20th century she strongly influenced the revitalisation of home cookery in the UK and beyond with articles and books about European cuisines and traditional British dishes).

And while I never met him, I have met Sarah Jackson, an associate professor of communication studies at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts who I met at the MIT Media Lab and who does great work revolving around how social and political identities are constructed and debated in U.S. culture. Last year she wrote a nice piece on Anthony which I have permission to republish … and it captures, for me, exactly what Anthony was all about:

Anthony Bourdain Was the Kind of ‘Bad Boy’ We Need More Of

When Anthony Bourdain visited the San Francisco Bay Area in 2015 for his CNN show “Anthony Bourdain:Parts Unknown,” he made a point of sitting down for a meal with one of the founders of the Black Panther Party, Bobby Seale. And he didn’t just talk about the food. He provided viewers an astute history of the group, its important role in the black freedom movement and the African-American community, and its suppression by the government.

I first watched that episode while at an airport waiting to board a flight, at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement had only recently entered public consciousness. Mr. Bourdain coolly narrated that the Black Panthers’ demands were “shockingly moderate: equality in education, housing, employment and basic civil rights,” an accurate statement but one that contradicts the misguided public perception of that unfairly demonized organization. I looked around at the group of mostly white Americans sharing my television screen, awed by how casually radical Mr. Bourdain’s commentary was.

Friday morning, when I heard of his death in France at age 61, I immediately rewatched that episode. I thought of how the world has lost more than a talented chef, writer and media personality. We also lost a man who brilliantly and bravely wove political education into food culture in a way that provided the kind of historical context and compassion for the oppressed that Americans need now more than ever.

In an era in which “woke” has morphed, for some, into a derisive term for those who are too earnest about injustice, Mr. Bourdain delivered this kind of insight effortlessly and without repentance. It was a secret ingredient baked into his every episode, and served to viewers whether they’d ordered it or not.

Throughout his career, Mr. Bourdain called for respect for immigrants, without whom, he never let us forget, the restaurant and agricultural industries in the United States would screech to a halt. During the presidential campaign, Mr. Bourdain did not shrink from assailing Donald Trump’s proposed wall at the Mexican border as “ludicrous and ugly,” and declaring we should be “honest about who is working in America now and who has been working in America for some time.” He argued for recognition of the value, creativity and labor of nonwhite and immigrant chefs, noting that it “is frankly a racist assumption that Mexican food or Indian food should be cheap.”

On both “Parts Unknown” and his earlier Travel Channel show “No Reservations,” he treated the people of the places he visited with compassion, modeling how to respect other cultures without exoticizing them. In Vietnam, a place he called one of his favorites, he offered a lesson on colonialism, war and American intervention. Likewise during episodes focused on Colombia, Iran, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, he would marvel at the beauty, the food, the literature and the generosity of the people. Then in the next breath, he’d contextualize stereotypes Americans might have about these cultures with lessons on Western imperialism, political violence and dictatorial regimes.

He also scrutinized inequality at home. He pondered the uniquely American history of Detroit, with insights about race, migration and gentrification. He exuded genuine respect for all of the people touched by these issues, discussing their history not with pity, but with nuance. Perhaps most remarkably, he did all this while also making us laugh.

His work represented a beautiful merging of love of food with an earnest effort to listen to others, especially marginalized people. After he visited Gaza, he openly criticized what he saw as the dehumanizing representation of Palestinians in the media, and proclaimed that the world was “robbing them of their basic humanity.”

Mr. Bourdain didn’t limit this inclusive and compassionate worldview to his television shows. He aligned himself with the rights of L.G.B.T. people, starring in an ad in support of marriage equality for the Human Rights Campaign and signing an amicus brief by a group of food industry professionals supporting the gay couple at the center of the Masterpiece Cakeshop case. He became an outspoken advocate of the Me Too movement, and an ally to women who experienced harassment and assault, forthrightly labeling Harvey Weinstein a “rapist” and sardonically calling out other powerful A-listers who remained silent on these issues. Here, he was doing the public messy work of tackling toxic masculinity, homophobia and misogyny, which he admitted had shaped his own life and actions.

Mr. Bourdain was not just curious about food and the world. He was aware that injustice and inequality are systemic issues, and he never shied away from pointing that out. He regularly humbled himself before people very unlike him, he asked careful questions, and he listened. Before our eyes, he was always learning, and trying to make the world just a little better.

We live in a time when the simplest protests against racial injustice by athletes and celebrities are considered divisive, and when admitting imperfection while striving for righteousness and truth makes you a rebel. Perhaps that partly explains why people called the curious and empathetic Mr. Bourdain a “bad boy.” If that’s the case, let’s have more like him. May his compassion and indignation live on.