3 June 2019 (Paris, France) – Amazon is pretty much the most secretive company in consumer tech. Apple gives almost all the operating metrics you could reasonably ask for, but Amazon has never disclosed unit sales for Kindle and is systematically opaque about every aspect of the business. It generally refuses even to comment on news stories.

However, there is one area where Amazon doesn’t stonewall: the warehouses and logistics operation. There’s a steady flow of informative and interesting press pieces on this topic. This is partly because it is more interesting to a general audience and partly because you can get raw material without going through Amazon – you can ask the workers and local people about a huge fulfilment centre. But it’s also because Amazon gives access: photographers and journalists are allowed in. And the warehouses make for great pictures.

But that is deliberate and it has everything to do with public relations because that coverage supports two narratives:

- Amazon offers very good value

- Amazon is impossible to compete with

So the Telephone Heads are dazed and confused (a ringing in their ears?) over last week’s rarity …an “exclusive” news blast about Amazon … from Thomson Reuters: “Amazon Interested in Buying Boost from T-Mobile, Sprint.” Boost Mobile is the prepaid cellphone wireless service used by T-Mobile and Sprint Corp, having 8 million users. What fun! Amazon’s “Chief Business Model Bulldozer”, Jeff Bezos, is on the scene! That guy who has a sixth sense for creating buzz, generating distraction, and whipping stakeholders into a frenzy of upside.

According to the news story:

It was not immediately clear why the largest U.S. online retailer would want the wireless network and spectrum.

Yep, that’s the incredible insight you get from most business media these days. Or this opinionette:

The U.S. Justice Department would need to scrutinize the buyer of a divested asset to ensure it would stay viable and preserve competition.

The Bezos bulldozer

No. That’s looking at it the wrong way, a complete misunderstanding of the world today. It’s about data. Let’s try to use a bit more creative thinking. The juiciest opportunities for Amazon to obtain data are … what? Here are a few choices:

1. Yes, Boost Mobile would give Amazon another service to sell. The company has been expanding its portfolio of Amazon-branded products, from batteries to apparel to kitchenware. Amazon already sells phones and, via third-party sellers, prepaid SIM cards. It’s not much of a stretch to think that Amazon could sell phones bundled with an Amazon-branded wireless service. Or maybe Amazon believes that in the present regulatory environment, it might be able to construct a 21st century version of the pre-Judge Green AT&T. But my view is that is not what Bezos is after. I go with the following three points.

2. Amazon wants to extend its data acquisition capabilities beyond its Alexa enabled devices

3. Amazon wants to kick start its data marketplace with information about “calls”, metadata about those calls, and enrich certain cross dataset analysis

4. Amazon understands that the regulatory environment is struggling with what might be called the “old school” methods of Facebook and Google … and has not a clue about “the Amazon construct”.

Note to the DoJ: we have been “platformed” by today’s information monopolies. There has been a complete overhaul of our data structure. Data-driven platforms have reshaped the material world we navigate, and they will stop at nothing to get this data. Yes, I am aware of your joint decision last week to split oversight: that the DoJ would look at Google, and the FTC would focus on Amazon. But I’ll wait and see if any investigation is launched and if you replace price as a measure of consumer harm in your antitrust template.

In my blog posts I often quote Philip Agre, especially his pioneering article from 1994 titled Surveillance and Capture which is about the way computing systems “capture” data. I love the word “capture”, an implication of a measure of violence as these systems force their environment (us) into the modus of data-engines. He predicted that we’d see a permanent translation of the flux of life into machine readable bits and bytes. And without using the word “platform” but in every sense of the word meaning platform, he said this was all due to the growing reliance on data-driven decision systems, systems “that would need ever more behavioral data as they move into cyberphysical systems. It will completely overhaul our existing information infrastructure, and the thirst for data will have no end”.

One of the things I detest about the Internet and how it has changed our thinking is the inexorable disappearance of retrospection and reminiscence from our digital lives. Our lives are increasingly lived in the present, completely detached even from the most recent of the pasts. And yet we have this enormous global information exchange at our disposal. So much of what we are experiencing now, often considered as “new”, has been addressed in detail in the past. Besides Agre, Nicholas Negroponte and his book “Being Digital”, originally published in January 1995, jumps to mind. His book provides a general history of several digital media technologies, many that Negroponte himself was directly involved in developing. He said “humanity is inevitably headed towards a future where everything that can will be digitalized (be it newspapers, entertainment, or sex) because we’ll get better at controlling “those unwieldy atoms”. He introduced the concept of a virtual daily newspaper (“customized for an individual’s tastes”), predicted the advent of web feeds, personal web portals, “mobile communications in your pocket”, and that “touch-screen technology would become a dominant interface”.

But in a sense, this is hardly surprising: the social beast that has taken over our digital lives has to be constantly fed with the most trivial of ephemera. And so we oblige, treating it to countless status updates and zetabytes of multimedia (almost three thousand photos are uploaded to Facebook every second!), and the latest “business news” which is really a press release or a paid ad (and rarely disclosed as such). This hunger for the present is deeply embedded in the very architecture and business models of social networking sites. Google and Facebook and Twitter and [insert your fav social media or news feed here] are not interested in what we were doing or thinking or writing 5 years ago, or 10 years ago, or 20 years ago; it’s what we are doing or thinking about right now that the systems say “we really need to know”.

How we have been “platformed”

What sets the new digital data superstars apart from historical firms is not their market dominance; many traditional companies have reached similarly commanding market shares in the past. What’s new about these companies is that they themselves are markets:

* Amazon operates a platform on which over $220 billion worth of goods are bought and sold each year

* Apple runs gigantic marketplaces for music, video, and software (soon to change this week)

* As the world’s largest music-streaming service, Spotify provides the biggest marketplace for songs

* The Chinese e-commerce behemoth Alibaba manages the world’s largest business-to-business marketplace.

* Meanwhile, Google and Facebook are not just the dominant search engine and the dominant social media platform, respectively; they also represent two of the world’s largest marketplaces for advertising space.

Yes, markets have been around for millennia; they are not an invention of the data age. But digital data superstar firms don’t operate traditional markets; theirs are rich with data. It’s why data protection is futile. Cesar Ghali of the Computer Science Department at the University of California Irvine has done a study of the networking architecture of social media (and media in general) and the dissemination/flow of information, looking at the collection of personal data and targeted advertising, and news sites, among others. In a nutshell … and you have certainly heard this before, especially from me … he says:

In today’s digital world, we’re continuing to upload more of our personal information to all of these interwebs in exchange for convenience. As such, some degree of information governance should be necessary to protect us. Companies should be held accountable for misusing people’s data. But this data is flowing into silos we are totally unaware of. This is the nature of the data beast. Besides, we do not really care to any serious degree. Why? Because the likes of Amazon and Facebook and Google generally making your life easier and/or better means the very algorithms that enable this need to be fueled by massive amounts of data. The more data they have, the more capable and sophisticated they become. And we’ll keep feeding them. Because they make life easy. It’s that simple.

Platformization has become the order of the day in every domain, not just Facebook/social media. Agriculture, retail trade, transportation, tourism, banking, finance, on-demand services: name it, and you can spot it. This shift has fostered monopolistic tendencies and market concentration across the economy.

And in Amazon’s case you need to go back just a little bit to the “good old days”. As the mobile revolution managed traction from some flawed limited slip differentials, the diffusion of tiny screens began. A trickle at first soon grew into a flood. Today, more than two thirds of online activity takes place on mobile devices; that is, tiny screens. And there was the problem. Different ad structures, pay scales, tech. Google’s infrastructure … a money gulping ad machine … learned mobile first. But then former Googlers working at Facebook knew how to tweak that wild and crazy social service to sell ads, too. So the Bezos bulldozer figured “hell, I want to get into the lucrative world of selling product ads, and man, have I got data!! What will advertisers pay to reach profiled, data mapped, verified users who are interested in my ad services?”

Because the primary challenge confronting us is no longer the ad-based revenue model for content services first adopted by platform companies; it is a new business model … data extractivism … predicated on digital intelligence solutions (both prepackaged and business-specific) that Big Tech companies offer for wide application across industries.

That’s why the tech giants demand a continuous stream of customer information from smart-home manufacturers. Yes, there are privacy “concerns” but they do not care. And if you are among my European readers and see a “GDPR issue”, well yes … kind of. They are covered by consents that follow the letter of the law, if not the spirit. And if you watched the BBC “Click” series on the GDPR last week and over the weekend you know the difficulty of tracking this data, or even knowing who has it … or even who the real data controller is.

Because as Amazon and Google work to place their smart speakers and smart devices at the center of the internet-connected home, both technology giants are expanding the amount of data they gather about customers who use their voice software to control other gadgets. For several years, Amazon and Google have collected data every time someone used a smart speaker to turn on a light or lock a door. Now they’re asking smart-home gadget makers such as Logitech (a plethora of devices) or Hunter Fan (“smart fans”) and a host of others to send a continuous stream of information.

In other words, for example, after you connect a light fixture to Alexa, Amazon wants to know every time the light is turned on or off, regardless of whether you asked Alexa to toggle the switch. Televisions must report the channel they’re set to. Smart locks must keep the company apprised whether or not the front door bolt is engaged.

Yes, this information may seem mundane compared with smartphone geolocation software that follows you around or the trove of personal data Facebook vacuums up based on your activity. But even gadgets as simple as light bulbs could enable tech companies to fill in blanks about their customers and use the data for marketing purposes. Having already amassed a digital record of activity in public spaces, tech companies know they must establishing a beachhead in the home. Why? Oh, you can learn all types of behaviors exhibited by a household based on their patterns.

“Hiding in plain sight”

So for Amazon, as regards the potential Boost Mobile acquisition which opened this post, the data acquisition capabilities are huge: data marketplace information about “calls”, metadata about those calls, and enriching cross-dataset analysis.

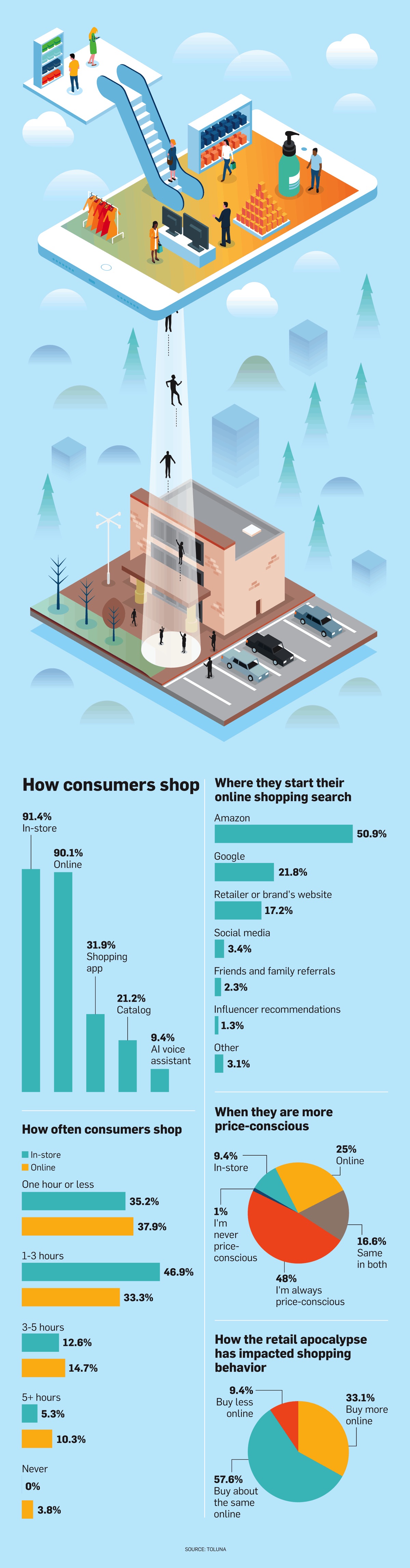

We often talk about Amazon as though it were a retailer. It’s an understandable mistake. After all, Amazon sells more clothing, electronics, toys, and books than any other company. Last year, Amazon captured nearly $1 of every $2 Americans spent online. As recently as 2017, most people looking to buy something online started at a search engine. Today, over 50% go straight to Amazon:

But to describe Amazon as a retailer is to misunderstand what the company actually is, and to miss the depth of what I called “the Amazon construct”, point #4 at the top of this post.

Because it’s not just that Amazon does many things besides sell stuff — that it manufactures thousands of products, from dress shirts to baby wipes, produces hit movies and television shows, delivers restaurant orders, offers loans, and will soon dispense prescription drugs. Jeff Bezos is after something so much bigger than any of this. His vision is for Amazon to control the underlying infrastructure of the economy. Amazon’s website is already the dominant platform for digital commerce. Its Web Services division controls 44 percent of the world’s cloud computing capacity and is relied on by everyone from Netflix to the Central Intelligence Agency. And its vast network of distribution infrastructure to handle it’s package delivery is now also being used by a host of other companies.

As Stacy Mitchell (a brilliant journalist whose focus in on concentrated economic power) said over three years ago in her in-depth report on Amazon’s power, scope and impact (soon to be a book) we have “a multi-trillion-dollar monopoly … hiding in plain sight.”

It also illustrates how the four most powerful companies that have ever existed – Google Apple Facebook Amazon, who have earned their own acronym “GAFA” – have achieved their remarkable dominance.

A few years ago when I was attending DEF CON in Las Vegas, I befriended a chap I will call “Insider”, a guy who still works for one of the GAFAs and often provides journalists insider information. Through his use of an authentication key he is able to work his way through layer upon layer of authentication checks in his employer’s databases. Once he showed me how he can track/collect all the many parts of my digital existence (and how to create false data avatars to throw off GAFA’s scent, tricks I still use today).

That these companies have ridiculous, mind-boggling amounts of data on each of us is certainly no surprise. As he told me:

Once your data hits our servers, thousands of different copies fly off in all directions. I’m not even too sure where this data ends up. Nobody does. Because once you’re exposed to one bit of the data collection operation you’re exposed to all bits of the operation. What we do is build what I call a “data cube” about you. I’m using all kinds of bits of information, pulling in more data from thousands of servers, putting it all together, then burying it all in machine readable code.

This data need is so copious within this tech giant, so woven into its DNA, that “Insider” needs to task thousands of computers spread across data farms and clusters all over the world to actually find and pull together all the information that is technically out there about you. This data universe, the creation of your “data cube”, is what all companies want. So now you understand how important it is to Amazon.

The point of all of this is to create what he calls your “fingerprint”. It’s also called “canvas fingerprinting” and “audio context fingerprinting”. But the primary point is to be able to track your movements all around the web, across all the different devices and Internet connections you use – an amazing constellation. It is made up of your browser, the model of your computer operating system, whether you have a JavaScript enabled, etc., etc. Fingerprinting is an entire industry and there is a technical paper that was produced in 2016 (I can provide a copy) that shows there are over 80,000 different entities using over 700 different increasingly exotic techniques to track people across the web. Each of these tech giants makes money in different ways but a great deal of what they are doing is simply trying to understand you.

That’s what Jaron Lanier (the father of virtual reality) is talking about in this book Who Owns the Future?, an examination of the power and challenge of making data useful. It’s why each of these tech giants has brought together these extraordinary teams of thousands of data scientists (“Insider” reckons Amazon has 2,500+ based on chats with his colleagues). It’s why specialized data science emerged to recognise patterns, establish links, discover the consistencies or anomalies or whatever was useful in this seething chaos of raw data.

When “Insider” showed be a lot of these pieces about me I realized what I actually had done … the real or primary things that I had done … were not as important as the inferences, the conclusions, the probabilistic guesses about what I might likely do next. And that’s something that you can never know about until somebody shows it to you.

It is why I have difficulty with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). I think Big Tech (its lawyers and lobbyists) played this perfectly: “Yes, let’s focus on protections designed to provide oversight and control over how data is collected and processed. Let’s talk about the ‘right to be forgotten’. Yes, it’s all about people’s privacy, identity, reputation, and autonomy”.

Big Tech kept our eyes off the real ball: protections not about the inputs, but the outputs of data processing. People should have been fighting for “the right to reasonable inferences”. European data protection law and jurisprudence currently fail in this regard. The GDPR … while laudable on many fronts … offers little protection against the novel risks of inferential analytics. And that is what Big Tech wanted to protect. And did. And THAT will require another post.