29 May 2019 (Brussels, BE) – Yesterday, as I was scanning material for my “Happy Birthday GDPR series”, a great piece popped up on the grid from The Washington Post on Apple from the Post’s technology editor, Geoffrey Fowler. Basically, if you leave your iPhone on, and even though the screen is off, the apps on your phone are beaming out lots of information about you. So dozens of marketing companies, research firms and other personal data guzzlers can get your phone number, email, exact location, digital fingerprint from your phone … oh, the list goes on. There is even a tracker that can identify your phone and creates a list of other trackers it can pair up with.

Yes, a dismaying lot of trackers (hellooo, Washington Post, I’m talking to you. You guys slurp like hell. Irony Alert!)

App trackers are like the cookies on websites that slow load times, waste battery life and cause creepy ads to follow you around the Internet. Except in apps, there’s little notice trackers are lurking and you can’t choose a different browser to block them.

The Post piece is very interesting as a look at the “secret life” in many of the devices you use every day, from your phone to those talking Alexa speakers to smart TVs. The piece is here but behind The Washington Post pay wall (which also prevents me from uploading it to my SlideShare account) so a summary. From the article:

My iPhone has been alarmingly busy. Even though the screen is off and I’m snoring, apps are beaming out lots of information about me to companies I’ve never heard of. Your iPhone probably is doing the same — and Apple could be doing more to stop it.

On a recent Monday night, a dozen marketing companies, research firms and other personal data guzzlers got reports from my iPhone. At 11:43 p.m., a company called Amplitude learned my phone number, email and exact location. At 3:58 a.m., another called Appboy got a digital fingerprint of my phone. At 6:25 a.m., a tracker called Demdex received a way to identify my phone and sent back a list of other trackers to pair up with […]

In a single week, I encountered over 5,400 trackers, mostly in apps, not including the incessant Yelp traffic. According to privacy firm Disconnect, which helped test my iPhone, those unwanted trackers would have spewed out 1.5 gigabytes of data over the span of a month. That’s half of an entire basic wireless service plan from AT&T.

Fowler had some help on this from a chap called Patrick Jackson, a former National Security Agency researcher who is chief technology officer for a mobile security firm called Disconnect. Jackson hooked up Fowler’s iPhone into the company’s special software so they could examine the traffic. In a world of data brokers, Jackson is the data breaker. Last year I wrote about an app he developed called Privacy Pro that identifies and blocks many trackers. And, yes, trackers are a big problem on phones running Google’s Android, too. Google won’t even let Disconnect’s tracker-protection software into its Play Store. (Google’s rules prohibit apps that might interfere with another app displaying ads.)

This all feeds into the big GDPR problem over “transparency” and why EU citizens are struggling with “Data Privacy and Data Subject Access Requests” mandated under the GDPR: if you don’t know where your data is going, how can you ever hope to keep it private? Or even get it? But first ….

The Washington Post report and app trackers need to be viewed in context

First, while there is much breathless reporting of data being sent to companies like Google and Facebook (ok, I am sometimes guilty, too, but my GDPR series tries to be balanced) the vast majority of it is innocuous. It’s simply developers using app analytics services provided by these companies, and they are learning things like which app features people do and don’t use.

Second, the Privacy Pro app that The Washington Post was using to monitor the tracker traffic was provided by a company that would like to sell you in-app purchases to block this traffic, so the company concerned has a vested interest in making the situation sound scarier than it is. I found this Jackson quote in the Post article full-on marketing:

This is your data. Why should it even leave your phone? Why should it be collected by someone when you don’t know what they’re going to do with it? I know the value of data, and I don’t want mine in any hands where it doesn’t need to be.

There is an argument that some tracking is actually legitimate, by necessity: some apps need to be sending tracking data in order to function. That Uber or Lyft car can only collect you if it knows where you are, for example. Many ecommerce and credit card apps use a variety of signals to detect fraudulent transactions, for example, and it’s in all our interests to block misuse of our cards. And there is an argument to be made that the more an app developer can learn about the way that real users interact with their app in the real world, the better they can make the app. Features that are used frequently can be prioritized for enhancement over ones that aren’t, and there are in-app behaviors that can identify problems with the functionality or user interface. App trackers play a key role in software quality.

But the cynic in me says it is irrelevant if a developer has a “legitimate” reason for the data. Who cares about their reasons. The users should still have specific control over what gets sent. Every app should require user approval of ALL data it is sending out … period. If a developer has a reason for this data then it is up to them to try convince the user to allow it to be sent. It should never be allowed for them to simply take the data they want simply because they say they need it for development purposes. And given we know that “anonymized” data and “innocuous data” are illusory … oh, never mind.

And, yes, we all know the goal of this technology: ad-serving. Nobody likes ads but whatever we think of them, they make it possible to enjoy everything from free apps to free websites. If you want those things to continue to be free, deal with it. Or get out.

But there is legitimate cause for concern

But Jackson does make three good points about app trackers.

First, transparency. He’s right that if we don’t know where our data is going, how can we ever hope to keep it private? There are quite literally thousands of trackers transmitting data which I will detail when my GDPR series continues, so it is going to be a nightmare to monitor all that traffic and figure out which uses are legitimate and which aren’t.

His second point, clear consumer protection policies, is good … and failing in the U.S. It’s not much better in Europe. To Jackson, any third party that collects and retains our data is suspect unless it also has pro-consumer privacy policies like limiting data retention time and anonymizing data … EU concepts. The problem is, the more places personal data flies, the harder it becomes to hold companies accountable for bad behavior — including inevitable breaches.

Third, he suggests Apple could also add controls into iOS like the ones built into Privacy Pro (slight hint he wants Apple to acquire him?) to give everyone more visibility. The point is a fair one. Apple does more than anyone else to protect user privacy, but this is an area where it’s impossible for users to get any kind of steer on what’s really going on under the hood. We either need Apple to do more … or for the law to do so. And you know how much faith I have in the law 🙂

The issue is not “privacy on everything or nothing!” The issue is privacy is a choice. It’s up to the user to decide and provide his consent based on clear description of procedures how his data is used and stored. That is … alledgedly … the GDPR mantra, which is failing in execution. The issue with Apple is that it provides only two options in privacy settings – all access/no access. So when you give access to your data it’s not restricting and can’t restrict the 3rd party apps to send it elsewhere. And difficult to control it.

And the arguments being made in the U.S. that revelation of your physical location “is not really” a 4th amendment violation because “it’s just a company”, or “it’s just metadata” … well, another blog post sometime, maybe.

The GDPR approach … and Apple slurping in Europe

My biggest beef about the GDPR has been this incessant focus on control. This idealized idea of control is impossible. Control is illusory. It’s a shell game. It’s mediated and engineered. Asking tech companies to “engineer user control” incentivizes self-dealing at the margins.

Even if there were some kind of perfected control interface, there is still a mind-boggling number of companies with which users have to interact. We have an information economy that relies on the flow of information across multiple contexts. How could you meaningful control all those relationships?

And what is interesting is that during the GDPR negotiation process (as indicated, we had an inside seat via a source) there were actually some pretty tech savvy folks on the EU Commission side (not many, but a few) who pushed for transparency requirements like “mobile apps must disclose all data collection in easy-to-understand terms,” “mobile apps must disclose any changes in their data collection or sharing practices,” and “mobile apps should re-alert the user every few weeks just to re-confirm users are ok with these terms.” The tech lobbyists didn’t quite like that … “way too onerous on our clients” … so that language/concept was dropped. But they are trying to revive the issues, again, in the ePrivacy Regulation having seen the manipulation during the GDPR process.

And Apple’s ad campaigns “What happens on your iPhone, stays on your iPhone” is … well … marketing. It comes across as Apple caring more about the idea of privacy as a selling point, as opposed to actually working to protect user data.

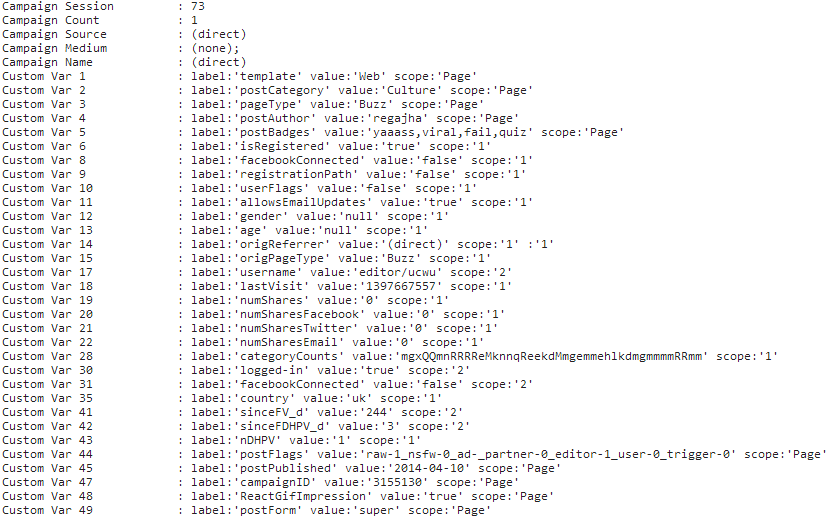

And how about iPhone slurping in the EU? A problem? I’ll leave you with this. Eric De Grasse (my Chief Technology Officer) and I use our own Privacy Pro-type software, provided by one of our cyber security partners. We did a short privacy check this morning. We encountered 2,233 trackers. Below is one tracker which was looking at page visits on one of our office iPhones (Eric and I both have bricked iPhones, set-up and programmed by our cyber partner. When full security is enabled, anybody trying to track me will think I am in Finland … and named Shirley). We won’t reveal the tracker just yet. We’ll save that for the next instalment of the GDPR series:

The key word to look for is “scope”. A scope of “1” means it’s something recorded about the user. Number “2” means it’s recorded about a page visit, while “page” means it’s a piece of information about the page itself you visited. The information can also capture a person’s age, and which country they are in, using the “tracker pairing” I noted in the first paragraph of this post.

See you next week when the GDPR series continues.