GUEST BLOGGER:

Eric De Grasse

Chief Technology Officer

Project Counsel Media

The FDA has laid out how it plans to handle self-learning algorithms in medicine

The FDA has laid out how it plans to handle self-learning algorithms in medicine

25 May 2019 (Washington, DC) – Last weekend I was about to jump a plane to head home to Paris after some very hectic days at the “Industrial Internet of Things World” conference (a brilliant blending of architecture, security, analytics and e-discovery which I wrote about here). But while in California I got a call that our media credentials had been accepted for one of Google’s “AI and Healthcare” workshops so I made a stop in D.C.

As I have written before, AI in healthcare is the use of complex algorithms and softwares to estimate human cognition in the analysis of complicated medical data. Specifically, AI is the ability for computer algorithms to approximate conclusions without direct human input. What distinguishes AI technology from traditional technologies in health care is the ability to gain information, process it and give a well-defined output to the end-user. AI does this through machine learning algorithms. These algorithms can recognize patterns in behavior and create its own logic.

While I was in D.C. for the Google event I learned about an intriguing program by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FTC). I tend to be a cynic when government tries to “do something” in any area of technology. But this FTC program really intrigued me. And I learned the agency was often ahead of the pack – ironic for a government agency. In 2009, when McKinsey & Company and IoT Analytics had calculated that, for the first time, the number of “things” connected to the Internet surpassed the number of people, the FTC had its first IoT workshop simply entitled “The Internet of Things”, with a subsequent workshop in 2015 entitled “The Internet of Things: Privacy and Security in a Connected World” which resulted in a detailed report summarizing the workshop and the FTC’s recommendations in this area. Wisely … and as the report says “consistent with the FTC’s mission to protect consumers in the commercial sphere” .. its discussion was limited to IoT devices sold to or used by consumers. It did not discuss devices sold in a business-to-business context, nor did it address the broader, and growing, development of machine-to-machine communications (one of the major reasons 5G was developed) which the report said “will become very challenging in the future”. Having just attended the most recent “Industrial Internet of Things World” conference referenced above, boy did they get that right.

The FTC is reviewing the future of medicine and wants your opinion on how it should handle machine learning. As the chaps at Google told me, the agency has been ahead of the curve with its thinking about connected devices and AI in medicine.

It’s essentially asking whether or not devices that continuously learn and change their algorithms based on new data should be evaluated under a new set of rules to ensure that those algorithm changes don’t compromise patient safety. Put another way, if a medical device learns and adapts treatment based on that learning, how does the agency make sure it’s learning correctly, and in a way that won’t harm patients?

So, for the full FTC report and the request for feedback on the topic of regulating machine learning just click here. Input is requested by June 3rd.

Thoughts

From a regulatory standpoint, machine learning is a tough one because in many cases it’s unclear how machine learning algorithms weigh information. Often it’s the outcomes themselves that we have to evaluate, but those outcomes will vary based on the individual and the amount of weight given to the individual’s data. And if the outcome is poor, it might be too late to fix the algorithm.

With that in mind, the FDA wants to look at several aspects of what it calls “Software as a Medical Device,” or SaMD. Among them are the risks and rewards of using a SaMD, which it aims to determine by asking questions such as: Is the device designed to help manage a condition? Is it designed to monitor overall wellness? Depending on the influence a particular device has on patient care, the FDA will hold the device to a higher standard. Diagnostic or management SaMDs will be held to the highest of all possible standards.

The FDA will also look at how the device evolves. Any device that uses machine learning and plans to adapt over time will be looked at to see how the machine learning algorithms it contains will change over time. The FDA recognizes three ways such a device may adapt:

The first is by changing its performance without changing either the data going into it or the way it will be used. For example, new data over time may help a software program get better at spotting breast cancer. So both the use case and the patient population stay the same, but the scanner improves.

The second is when a machine adds new inputs to address the same problems. So for example, a monitoring device might start incorporating heart rate data as part of an algorithm designed to determine wellness.

The third involves a change in the use case thanks to better ML algorithms. For example, perhaps a scanner has traditionally been awesome at detecting breast cancer in white women, but thanks to new data it can now accurately detect breast cancer in African-American women, too. The FDA considers a new patient population or a new diagnostic ability to be a change in the use case. It would also consider new weight given to different inputs as falling under the use case change category.

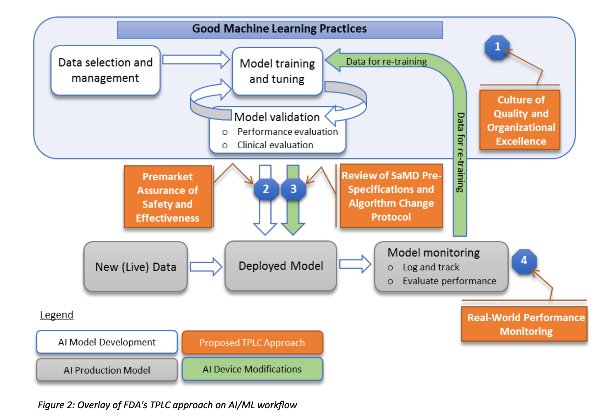

The agency wants to know if these classifications make the most sense and how it should ensure that changing input or the weight given to inputs remains safe for patients. The next area that concerns the FDA is how to make sure any algorithm adjustments are tested and then executed. The FDA doesn’t want companies to have a culture of “moving fast and breaking things” when it comes to building algorithms for diagnostics or patient care. And it plans to offer a good approach to machine learning, as laid out in the image above.

The goal is to ensure there are ways to measure the outcomes of algorithms over the lifetime of the product and that any company that makes a software-based medical device doesn’t just fling the product over the wall and forget about it. So instead of testing a drug and releasing it, a software-based medical device incorporating machine learning would have continued testing — the results of which would be transparent to regulators and consumers alike. The FDA wants to know if this is a good approach, as well as how medical device companies would have to restructure their testing operations to make it work.

After explaining in the report how it views the challenge of regulating machine learning in medical devices, the FDA tries to explain how it might handle various products, ranging from intensive care unit management software to a smartphone app that detects skin cancer. It then lays out what types of changes would trigger a new review and why.

As a consumer of medicine (aren’t we all?), I like that the FDA will ensure any changes in the incoming data and expansion of use cases will trigger a more comprehensive review. I also like that the agency wants device makers to show it their data as well as how they annotate and handle that data, and that device performance is monitored over time.

As I said above, I tend to be a cynic when government tries to “do something” in any area of technology. But these rules will trigger changes in how devices are brought to market. It will also create new burdens for companies in the medical space. But I think it’s important for a regulatory agency to share how it’s thinking about the changes that connectivity brings to devices. As we add software and self-learning algorithms in more places (such as cars or even lighting systems), companies and other agencies should view the FDA’s initiative as a good example to follow.

Oh, and a short note on Alexa which relates to the above story …

As I noted in my coverage of the “Industrial Internet of Things World” conference, with 13,000+ attendees and 300+ exhibitors and 12 session/panel tracks even with a 4-person team there is a lot to cover. But the FTC story jogged the memory banks so I thought I’d share this bit because it relates.

Alexa is getting smarter. Two members of the data science team working on Amazon’s Alexa digital assistant shared some insights into how Alexa will continue to evolve. The scientists explained that soon Alexa will be able to answer queries before being asked them by using transfer learning, which is a style of machine learning that takes expertise in one area and applies it to another one. This is basically how humans learn, and it’s somewhat of a holy grail in AI.

You probably use Alexa mostly for things like checking the weather or controlling your home’s smart lights. In the near future, however, Amazon says Alexa will be able to not only handle more complex requests but also answer questions you didn’t even ask.

Here’s how they framed it:

A child who touches a candle flame and gets burned will quickly learn that yellow-orange objects are hazardous, but will learn to distinguish that, say, a light bulb is a threat but a flower is not. This is the kind of learning humans are great at but A.I.’s are still in the early innings.

But soon this type of learning will allow Alexa [note: Amazon said 100 million devices have been sold worldwide] to anticipate requests. If you live in New York and ask your Echo for next week’s weather in Boston, for example, it will anticipate that you have an upcoming trip and follow up on its answer by asking if you’d like to hear flight or hotel options.

What Alexa is great at right now is completing transactional requests. In the next few years you’ll find it adds more and more utility, more and more functionality, and more and more fun. It will become more conversational.

One of the challenges, of course, is gathering the huge amounts of data Amazon needs to improve its artificial intelligence while also ensuring customers that it’s protecting their privacy. The company faced significant criticism last year when an Echo device recorded a couple’s conversation, then emailed it to a someone on their contact list. Amazon said the device had misinterpreted parts of the conversation as commands to do so.

This is still mostly theoretical, but Amazon is pushing the envelope.