As the GDPR turns one year old, a look at obfuscation, corporate trickery, and the enforcement blues

(Part 1 of a 4 Part series)

GDPR: the regulator’s view

GDPR: the corporate view

-

There continues to be confusion, poor understanding of the law at EU Data Protection Authority offices. Or just frustration.

-

There continues to be a legal “war zone” as obuscation and corporate trickery ramps up. First up: how to manipulate Data Privacy and Data Subject Access Requests.

- What GDPR misses is not the issue of data minimization but that these platforms exercise quasi-sovereign powers to actually institute a quasi-totalitarian rule across the many contexts we navigate. Data control is not the issue.

20 May 2019 (Brussels, Belgium) – When it comes to events and workshops about the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) … really any data privacy event … I tend to steer clear of legal-orientated tech events and try to attend only conferences that have a healthy interdisciplinary team of legal scholars, business mavens, computer scientists, cognitive scientists, and tech geeks. The legal-orientated tech events tend to be top heavy with people who don’t actually “do” GDPR but just recite the law, say “you must comply as follows” because … well, they are there to put the fear of God in you and just sell their services. Not tell you the full story. And in many cases the law firms on these panels are the same ones advising Big Tech in the first place. For all of them it’s just about the money.

It’s why I make sure my crew and I are out there attending an esoteric collection of law and technology conferences, quizzing regulators, doing our own research. My role is to DJ the internet, to do deep dives into all subjects and to deliver to my readers daily mixes of fresh ideas. My team and I search each day to find different angles and points of view that lead to deeper understanding. Industry insights, stories from the “dark side”, etc.

We are navigating … with a great amount of difficulty … an historic transition with digital technology and artificial intelligence. Our dominant storytelling must change. Silicon Valley people went from being heroes to antiheroes in the space of a few elections (2016 in the United States; Brexit in the UK). And when you talk with them, they are as confused as everyone else on how it all flipped. Because they aren’t different people nor are they doing things that dramatically different. It’s the same game as before.

The reality is that the problems that are causing so much turmoil in the world predate the digital and computational acceleration, but are also very much aided by it. It’s not either/or at all. The problem is the creators of all this wonderful technical infrastructure we live in are under social and legal pressure to comply with expectations that can be difficult to translate into computational and business logics. This stuff is about privacy engineering and information security and data economics. Dramatically amplifying the privacy impacts of these technologies are transformations in the software engineering industry – with the shift from shrink-wrap software to services – spawning an agile and ever more powerful information industry. The resulting technologies like social media, user generated content sites, and the rise of data brokers who bridged this new-fangled sector with traditional industries, all contribute to a data landscape filled with privacy perils. You need folks that can fully explain the technical realities.

There is still a mind-boggling number of companies with which users have to interact. We have an information economy that relies on the flow of information across multiple contexts. How could you meaningful control all those relationships? When “data control” is the north star, lawmakers aren’t left with much to work with. And the GDPR does not address these issues because its drafters did not understand or even recognise them. But the tech companies did.

As I have noted before (and as I will elaborate in Part 2), all the sound and fury about GDPR was about “control” of personal data as core to privacy. And so we have a GDPR that forces complex control burdens on citizens, or make rules that mandate deletion or forbid collection in the first place for high risk activities.

But the regulators got it bassackwards. Fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy (ok, democracy is dead; topic for another post) should require that individuals control and manage their own data … and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies steered the GDPR negotiations the other way (our team followed the negotiations and we had several inside sources) so they knew it would become too late (the Commission had set itself a ridiculous timeline to get the GDPR done) to impose the proper structure and they made sure any new laws that sought to redress issues would work in their favor. And knowing the Commission was still hooked on the 20th century concept that “monetary fines” would be the appropriate remedy and would steer clear of structural change penalties, they clapped their hands with glee.

It has been the same with artificial intelligence (AI). In early April, the European Commission published guidelines intended to keep any artificial intelligence technology used on the EU’s 500 million citizens “trustworthy”. The bloc’s commissioner for digital economy and society, Bulgaria’s Mariya Gabriel, called them “a solid foundation based on EU values.” But many of the 52 experts who worked on the AI guidelines (having learned the errors of their way in negotiating the GDPR the Commission brought everybody into this one), argued that the foundation was flawed, not what they had recommended — thanks to the tech industry. Thomas Metzinger, a philosopher from the University of Mainz, in Germany, has gone on record to say that too many of the experts who created the guidelines came from or were aligned with industry interests. And they were the ones that held sway. He and other “non-aligned” experts were asked to draft a list of AI uses that should be prohibited. In effect, a “red line” list around the uses of AI. Very tight restrictions on the tech companies. But when the formal draft was released all those “red lines” were presented just as examples of “critical concerns.” One Commission member involved in the negotiation told me “well, you know, it’s complicated. I think the work was balanced, and not tilted toward industry. But we needed to make sure we did not stop European innovation and welfare, and we also had to avoid the risks of misuse of AI, or at least draw attention to them. It was a balancing act.” For sure.

The brouhaha over Europe’s guidelines for AI … just like the skirmishes over data privacy … are about installing “guardrails” to prevent harm to society. Tech companies will always take a close interest – and do everything in their power to steer construction of any new guardrails to their own benefit.

We’ve had a few GDPR fines (details coming in Part 2) but we still have only a hazy sense of what a strong or weak GDPR case looks like. Expect a few more “headline fines” (regulators are under pressure to “produce”) but look for years of legal trench warfare on the big stuff. Yes, we are a year into the GDPR regime, but there’s simply no roadmap for how it will be used.

More on guardrails, monetary fines, Big Tech manipulation, etc. in Part 2. First, some fun stuff: how to manipulate Data Privacy and Data Subject Access Requests.

“You want what? Your data? What data?”

The GDPR makes it so clear, so easy. Individuals have the right to access their personal data. This is commonly referred to as subject access. Individuals can make a subject access request verbally or in writing. Companies have one month to respond to a request. Easy peasy.

Well, ok, maybe not so easy peasy. Just for fun, I had my staff (now numbering 10) file multiple Data Subject Access Requests. Hilarity ensued. And, yes, I know. The GDPR is clear: the controller shall upon request provide a copy of all personal data they have plus information about the processing. The devil, dear reader, is in the details. If there is a system, it can be gamed.

Note: the stories below have been “cleansed” and redacted, partly because I am litigation adverse (especially suits against me), but also because all of this has all been submitted to “The Guardian” who are fact-checking and may use it for an upcoming story on the GDPR.

Your data: it ain’t so simple

And before you go barging off with your Data Subject Access Requests, some background. When you ask for your data back, there are actually three layers that companies hold.

1. Data you’ve volunteered

2. Data that’s been generated about you

3. Data that’s been inferred.

Note: you can also say there is a special level, “4”. That’s data that other people have given the tech companies or other company. If I add your phone and email address to my Android phone address book, I’ve just given your data to Google. Or the case of a small business that has done work for you and needs your emergency contact details: name, address, phone. I did not address this issue in this post.

With patience (see below) you will (probably) get “1”, sometimes get “2”, but you most likely never get “3”.

Because it is Layer 3 is where the action happens. This is what the tech companies fought mightily to preserve. This is the “inference data point” conundrum I have written about before. The company algorithms determine they have 30 given criteria data points, identifiably as “me”. But the 31st point has a likelihood of being something being true about me, but it is something they’ve calculated. It’s their intellectual property (IP). It’s not a personal data point. But I’m sure it is identifiably “me”. We are in the “probabilistic nature of data science” and the “inference” area. It’s an area where the consequential parts of our data existences are also the bits furthest away from our control or knowledge.

And it depends on how we define “infer”. If an organization can take 30 bits of data about me and use a whizzy black box to determine how likely I am to fit data point 31, then that process is entirely of their making. I can demand the 30 but the 31st is in no sense “my data”. If it is about you – as in it relates identifiably back to you – then you CAN make an argument that it’s “personally identifiable data”, but under the GDPR you do not have ownership per se.

NOTE: there is actually specific guidance about the data portability right in GDPR that says inferred data isn’t covered (click here), one of several limitations to the effectiveness of the GDPR.

I will address this in much more detail in Part 2. It is THE most important aspect about the GDPR (and as I indicated, tech companies argued strenuously about it) because the big point here is that 31st data point is likely the one that really affects people.

And it is why the GDPR is such a tricky beast. Because data rights are about “information power”. The real power, the struggle over things like “fair processing” all happens with inferred data that companies are most likely to see as their IP and least likely as personal data. It is why IP was such a fire point in the GDPR negotiations.

The games of obfuscation

First of all, there is an astounding amount of friction companies put in the way of you doing things they don’t want you to do. Trying to use GDPR to get our data, they are at the top of their game. We’ve came across:

– Account sign-ups that don’t work

– Postal mail addresses

– Broken links

– Endlessly ringing numbers

– Or just no response

Or one of the my favorites: “We don’t have any data on you”. I have bazillions of devices, I use countless online services. How can it be, that I’ve miraculously slipped through the net? Either these data-rich companies have far less impressive datasets than they claim. Or it’s a storage issue as one advertising contact told me:

It costs a ton of money to run a full Data Warehousing/BI operation so many companies don’t, relying on their limited CRM systems that may just about hold your name and your past purchases but unlikely to hold much else. The cost of holding your device data, etc. is just too high.

Nah. The cynic in me says their data access rights systems are simply (deliberately) not being interpreted correctly.

Some other points:

– Excruciating formats many companies request, although the GDPR states that a subject data request can be submitted in any format. It necessities a flurry of email exchanges. And many companies say “just make a oral request” … thereby making it difficult to evidence the request.

– Sending endless scans of your passport. What on earth is the point in sending photo identification via email, when the receiver is completely unable to verify what you look like?

– Another favourite: sending proof of address for services that don’t know your address.

– Printing out, signing, scanning and sending a letter saying “I am who I say I am” is just time consuming, and it’s not safe.

And time-after-time-after-time, a common response:

US: “we are evoking the GDPR to return all the personal data you hold on me”

THEM: “we are not the data controller for the data you’re asking for”

US: “you ARE the damn data controller for the data we’re asking for!!”

And then there are the regulators

Sometimes it’s almost quaint. When we contacted the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) to complain about these issues (in our process we contacted regulators in Belgium, France, Italy and the UK) we were having with getting our GDPR data, they send us a link for a downloadable Word document to submit a complaint … an incredibly frustrating form … and we found out after calling an ICO employee we know that they have a team of people that manually transfer the emailed Word doc into an internal records system for review. Because the internal records system is not set up to automatically input the Word doc. It delays the entire process.

Or when we told a company they have no reason to hold our data and they said “yes, we do” … try raising your concerns with the ICO. You will be told (we recorded the conversation) “we checked and the corporate entity claims it has a valid business reason for needing this data therefore there’s nothing we can do”. That was it. Phone call ended.

Or our favourite, voiced by many regulators:

NDPO (national data protection office): “We’d like to help but you need to take this complaint to the Irish DPO”

US: “But I’m a xxx citizen and you are my DPO”.

NDPO: “Yes, but the lead regulator is in the country in which the tech firms has its data controller – and in your case, Ireland”.

US: “But this adds a layer of needless complexity”

NDPO: “Look, I am very sorry, but we cannot help. And we have 15,000 of these complaints to sift through”.

Whether they really have 15,000 complaints we do not know. I rely on the “post-GDPR enactment” studies done by Cisco in its “Data Privacy Benchmark Study” series (due for an update), along with the DLA Piper GDPR study and IAPP review which, taken as a group, are pretty accurate on investigations, filings and fines imposed.

But speak with just about any privacy experts, data watchdogs, academics and even regulators in other countries and you will get a similar response: the GDPR, the product of years of wrangling with data companies, is vulnerable because of the one provision on which the tech companies prevailed: that the lead regulator be in the country in which the tech firms have their “data controller” – in most cases, Ireland. Because what you had was an “attractiveness competition” between EU countries.

Ireland’s willingness to crack down on the companies that dominate its economy has long been questionable. No news here. But Ireland’s failure to safeguard huge stores of personal information looms larger now that the country is the primary regulator responsible for protecting the health information, email addresses, financial records, relationship status, search histories and friend lists for hundreds of millions of Americans, Europeans and other users around the globe.

As I have written before, in Ireland is the appearance of an investigation rather than the substance of one. Ireland continues to take a more corporate-friendly approach to regulation than many of its EU counterparts, openly favoring negotiation over sanctions and lists of questions over on-site inspections. Those last two powerful tools … sanctions and on-site inspections … are never authorized but used by all other national data protection offices.

And when we did get our data?

Not all companies were uncooperative. But some wild stuff. With one company, after two months spent pulling teeth using GDPR, one of my staffers got some pretty weird scores companies compiled about her:

– “Indulgence Rank” (how susceptible were you to impulse buy)

– Probability: your regular interest in crosswords

– Animal/Nature awareness level

– Funeral Plan – Ranked “likelihood to have one”

Another staffer:

– Something called an ‘onliner segmentation’ (I’m a “cyber cafe student”)

– The specific probability that you work in pretty much any job imaginable

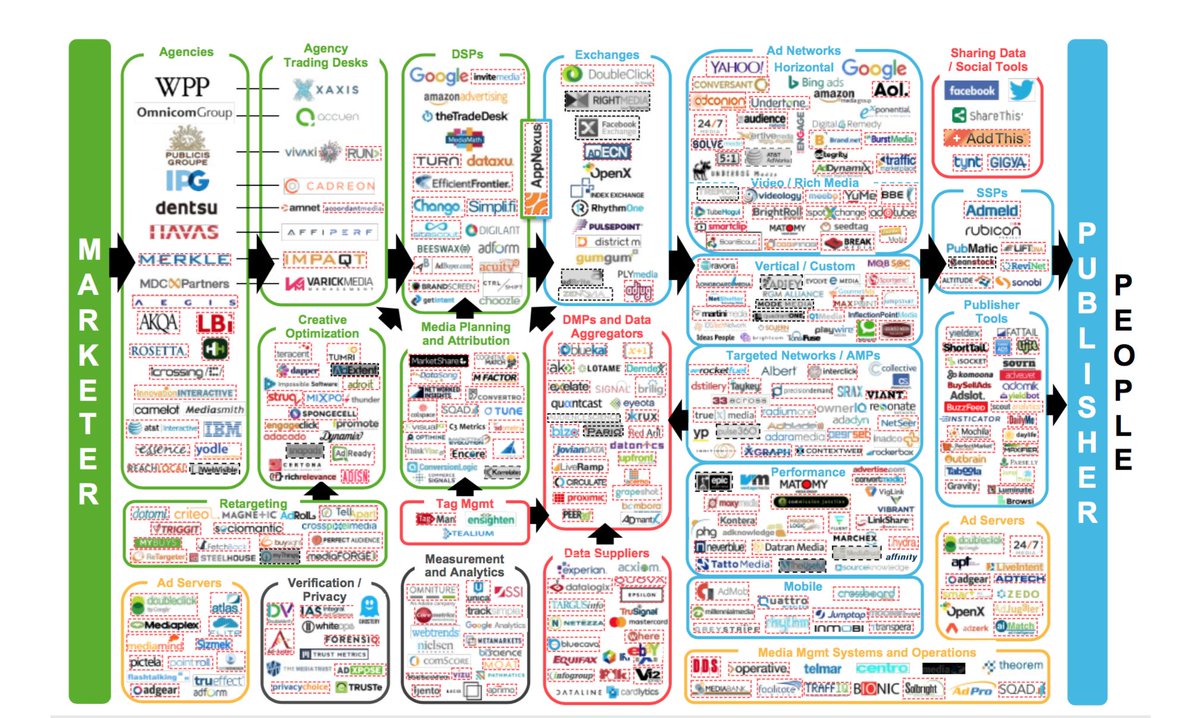

Then there is ad-tech, which I have written about extensively given the data protection work I do is almost all for advertising/digital media companies. The term “ad tech” is short for advertising technology, and broadly refers to different types of analytics and digital tools used in the context of advertising. Discussions about ad tech often revolve around the extensive and complex systems used to direct advertising to individuals and specific target audiences. I will have more about it in Part 2 because the GDPR issues are huge.

It’s a shadowy world. There are a huge number of companies. The following graphic shows the dominant players, and my guess is you haven’t heard of many of them before. But they’ve certainly heard of you. No less than 48 had data identifiable to my staffers … and it took a special “cookiebot” given to me by an advertising client to track these connections.

Ad tech companies are extensively tracking EU citizens who visit non-ad funded government and public sector websites. Even on sites featuring sensitive health information, vulnerable citizens are unknowingly being tracked. EU governments and public sectors are thereby – unintentionally – serving as platforms for online commercial surveillance.

Coming in Part 2: the Google/Ireland case could be a doozy

So … we now have the first major standoff between Google and the Irish Data Protection Commissioner, Google’s lead privacy regulator in Europe, as announced last week. Raising the many difficult questions about how the ad giant handles personal data across the internet. It will be an interesting look at how Google treats personal data at each stage of its ad-tracking system.

And, yes, there were a few raised eyebrows. Ok, a lot of raised eyebrows. As I wrote in previous posts, in Ireland it is the appearance of an investigation rather than the substance of one. Ireland continues to take a more corporate-friendly approach to regulation than many of its EU counterparts, openly favoring negotiation over sanctions and lists of questions over on-site inspections. Those last two powerful tools … sanctions and on-site inspections … are never authorized but used by all other national data protection offices.

Which will make this new Google probe — interesting. Especially since it addresses the three different parts to your data-self:

1. The small amount of data you actually volunteer

2. The data generated when you use a service or device (see BBC show above)

3. And the far the most interesting data that has itself been created from other data that had been collected

It’s this last bit of data that is the “Holy Grail” for Big Tech and advertisers because it generates the “behaviorally” targeted advert.

More to come.