The European tech sector is “Waiting for Godot”.

The European tech sector is “Waiting for Godot”.

Or is it “Goodot”?

(thanks for the graphic, Peter)

19 May 2019 (Paris, France) – In Samuel Beckett’s original French-language play “En attendant Godot” (Beckett translated it into English himself due to popular demand, adding the subtitle “a tragicomedy in two acts”) two bedraggled companions (the philosophical Vladimir and the weary Estragon) wait for the arrival of someone named Godot who never arrives, engaging in a variety of discussions and encountering other characters. In one of the more memorable lines Estragon sums up the European tech market:

I suppose we are lucky to have no expectations, to just allow things to happen to us and around us.

Unfair? Well, read on and see what you think.

We do have SOME stuff

On the positive side, the continent has world-class companies in fields like biotechnology, luxury cars and nuclear energy, manufacturing sectors incorporating sophisticated software (BMW is considered to have the best mass-produced high-tech car in the market these days, described by one auto analyst as “a computer on wheels as much as it is a car”). London is home to DeepMind, a leading artificial intelligence outfit; Stockholm is home to Spotify, a dominant music-sharing service; Cambridge-based Arm makes processor chips for almost all the world’s smartphones.

Yet, still, Europe lacks large firms in areas like social media, e-commerce and cloud computing comparable in scale to America’s Google and Microsoft, or China’s Alibaba and Baidu. Of the world’s 15 largest digital firms, all are American or Chinese. Of the top 200, eight are European. Such firms matter. They operate dominant online platforms and are writing the rules of the new economy.

Mariya Gabriel, the EU’s digital economy commissioner, noted at VivaTech this year that Silicon Valley and China now make the big decisions about the internet, and this affects European domestic policy. She is right. Even BMW, for example, does much of its cutting-edge research in California and Shanghai. In Brussels, officials talk of a “Sputnik moment”, a sudden realization of its technological disadvantage, akin to America’s when the Soviet Union put the first satellite into space in 1957.

VivaTech

Here in Paris, we just wrapped up the fourth annual Viva Technology event – known as VivaTech – which was housed at the massive Porte de Versailles expo center. It requires a massive venue. The event officially clocked in 110,000+ attendees and there were 9,000 start-ups … you read right … that had exhibit stalls and/or made presentations. That’s in addition to the other 600+ exhibitors and 300+ speakers. And this year there were some pretty big names amongst the speakers: Usain Bolt (he was pitching electric scooters!), John Kerry Jack Ma, Emmanuel Macron, Holly Ridings (NASA’s first woman chief flight director), Ginni Rometty, Justin Trudeau, and a host of Big Tech execs. With a healthy mix of cringeworthy anecdotes. So, yes … it’s a REALLY big tech conference.

It’s one of the few events I attend with my media/tech team without our video crew in tow, and which I was not on a panel or part of the event itself. Over the years I realized it is a monumental undertaking to try and understand the digital technologies associated with Silicon Valley — social media platforms, big data, mobile technology and artificial intelligence that are increasingly dominating economic, political and social life – so for certain events (like this one) it is best to just fan out and absorb as much as we can. Just chat with advertising/digital media mavens, data scientists, data engineers, social media techies, psychologists, etc. And collect reams of white papers to track the evolving thinking and development of these technologies.

What makes VivaTech different from other big tech conferences, though, is its distinctly European saveur. With prominent backing from the French state (VivaTech was founded in 2016 by Publicis Groupe and Groupe Les Echos) it has an explicit aim to “help more European unicorns emerge.” And as Mariya Gabriel noted above, it is squeezed between the established Silicon Valley titans and the growing might of Asian tech giants, Europe has long struggled to shepherd many home-grown beasts to sufficient size in the modern tech barnyard – er, economy. Hence those 9,000 startups showcasing their wares and looking to raise funds or partner up with the bevy of big companies that are here to see the latest that Europe’s tech scene has to offer.

And there were scores of hands-on workshops. Just one example was the “Hacking Room” run by the French telecom company Orange:

Here you could actually try being a hacker. They had multiple programs that ran you through the nuts and bolts of cybersecurty threats.

Stuck in the middle with vous

VivaTech is all about European innovation, but it takes place against the backdrop of the increasingly acrimonious trade war between the US and China that is rippling through Europe. Chinese telecom equipment group Huawei is a prominent target of the Trump administration’s ire, effectively banned from selling its gear in America and seeing customers around the world come under pressure to drop contracts for fear of retaliation against their American operations.

But what does this matter to the masses of startups scrounging for angel investments and seed rounds? Any company with dreams of scaling up will, eventually, be forced to reckon with geopolitics of one sort or another. With the world’s great powers now squaring off over the fundamental building blocks of the digital economy – data privacy, 5G networks, and the like – it’s not something that founders can afford to ignore.

Can Europe compete? Looking at some hard numbers

“France is maybe the best place to start a company” said Jean-Rémi Kouchakji, co-founder of PayinTech, a Paris-based fintech firm that was among those 9,000 startups at VivaTech this year. Paradoxically, he said, it’s a difficult place for small- and medium-sized companies to thrive, a necessary step for building a corporate titan.

At the moment, Europe is good at thinking small. France, in particular, has more than enough technical talent to go around, and generous tax credits to help startups get off the ground. But as companies grow, they hit the country’s infamous 50-employee ceiling, above which onerous labor regulations and red tape is applied. Talk to any tech company and they will tell you the same thing: “Over 50 people, it’s hell”. But few are anywhere near these numbers.

And having one French-based company I can tell you: the thicket of regulations that threaten startups as they grow shows why firms may be wary of ramping up quickly, and why investors could be reluctant to pour capital into them. It’s no wonder that France lags behind the UK on most measures of tech entrepreneurial success, much less the U.S. and China.

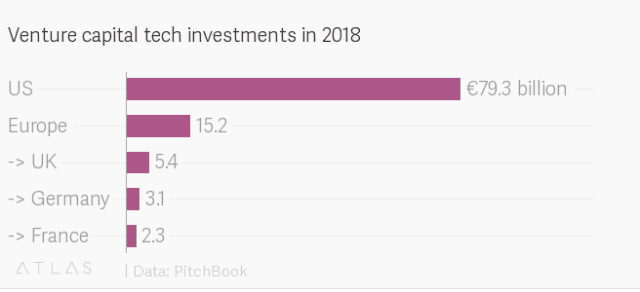

And like everywhere else in Europe, French tech companies are deeply underfunded relative to the U.S.:

Now, all is not gloom and doom. The founders we met, from France and elsewhere in Europe, had support from startup accelerators and incubators that provided networking, knowhow, and – yes – money. Government officials acknowledged the fragmentation in markets for capital and digital services that hinders tech companies from taking full advantage of Europe’s market of 500 million consumers.

And that begs the long-running question – why hasn’t Europe created tech giants like China and the U.S. – which was played out in dozens of forms during the conference. On the main stage, the star power of tech-sector heavyweights like Alibaba’s Jack Ma could only be matched on the European side by the likes of French president Emmanuel Macron. There was no European corporate equivalent to match Ma. Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Huawei erected big booths that stood out amidst the mix of France’s old-economy firms like energy utility EDF, aerospace contractor Thales, and railway operator SNCF.

The reasons why Europe’s tech players are lagging behind are well known and I am treading well-worn ground here: the continent remains fragmented, with differing rules and licensing from one (small) nation to another. Another big factor is money (see the chart above). Large funding rounds allow startups to expand quickly and gobble up market share. Growth capital in Europe, while improving, is nowhere near as plentiful as in America. The U.S. also boasts deeper public capital markets for venture-backed companies to cash out, as a herd of unicorns now coming to market have shown.

Oh, yeah, that Vestager lady was there

So just a short walk from the sprawling VivaTech booths run by Facebook and Google (they had huge booths) EU competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager was on stage with their fate in her hands. Kind of. One solution to Facebook’s growing dominance, as recently suggested by co-founder Chris Hughes, is to break it up – perhaps splitting off WhatsApp and Instagram from the rest of the social network.

Vestager said that would be a last resort, “and likely not going to happen“. Why? Because as she said “it would probably get bogged down in court for a decade or more”. She should know. Her famed decision against Google took DG COMP eight years to complete … aimed to “crimp Google’s behavior in key ways”. What happened? The industry changed massively over those eight years and DG COMP dealt with just one part of a problem that is now very large and sprawling – these platforms developed quasi-sovereign powers to actually institute a quasi-totalitarian rule across the many contexts we navigate.

Zuckerberg, however, may find Vestager’s other suggestion to rein his company in just about as unappealing: forcing Facebook to open up its vast stores of data to competitors:

We think much more about access to data when it comes to, for instance, misuse of position of a monopoly. If you have no access to data, you won’t be able to make it in the market because you cannot access potential customers.

I am addressing all of these issues in my series “The many plans proposed to regulate social media are the equivalent of putting a band aid on a bullet wound. And just as futile.” (click here)

TO CAP THIS OFF, JUST A WEE BIT OF HISTORY AND PERSPECTIVE

I have a tsunami of material, collected for a book I am writing. The following is just a few research notes:

Europe’s history explains the “European tech lag”

Europe’s history explains the “European tech lag”. In the 18th century, its lack of standardization made it the cradle of the industrial revolution. Rules and markets varied. Entrepreneurs who did not find support or luck in one country could find it in another. All this created competition and variety.

But today Europe’s patchwork is a disadvantage. New technologies require vast lakes of data, skilled labor and capital. Despite the EU’s single market, in Europe these often remain in national ponds. Language divides get in the way. Vast, speculative long-term capital investments that make firms like Uber possible are too rarely available on European national markets. True, there is progress. European universities are working more closely together, and in 2015 the EU adopted a new digital strategy that has simplified tax rules, ended roaming charges and removed barriers to cross-border online content sales. But about half of its measures – like smoother flows of data – remain mere proposals. And as I will note in a piece later this week, to “celebrate” its first birthday, the new GDPR has created a host of such unintended consequences.

In the 19th century Europe was the first continent to industrialize, and institutions based on that experience have deeper roots there than elsewhere. As Ian Inkster notes in his History of Technology:

Most European countries are still run by marmoreal Christian or social democrats descended from the struggle between bourgeoisie and workers. Their propensity for bold thinking is limited. European investors expect to be able to claim physical assets against their losses if a firm goes bust—bedevilling software startups than tend to lack them. Research is too often incremental, not radical. The burden of early industrialisation is also something of a geographic tale. Europe’s traditional industrial heartlands are struggling to adapt to the new digital era, but those once on the periphery—Bavaria and Swabia in Germany, and cities like Helsinki, Tallinn, Cambridge and Montpellier—are leading the way, without the institutional fetters of old factory towns like Liège.

The 20th century also restrains Europe’s technological competitiveness today. The collective experience of Nazi and Soviet surveillance and dictatorship makes many Europeans protective of their data (Germans, for example, are still reluctant to use electronic payments). Moreover, since 1945 the continent has mostly been at peace and protected by outsiders. So it has no institutions comparable to DARPA, the American military-research institution where technologies like microchips, GPS and the internet were born. Nor has it anything comparable to China’s military investments in technology today.

Oh, and the migration issue

The equivalent historical forces in the 21st century could prove to be differing attitudes to migration. America’s technological superiority is built on its ability to attract talented, success-hungry people, one reason businesses resist Republican plans to limit legal immigration. Of the 98 high-tech firms in the Fortune 500, 45 (including Apple and Google) were founded by immigrants or their children. China lacks immigration but sends many of its young abroad to study, and then repatriates their skills. Europe does neither and treats migration as a threat, as its debates about how best to seal off the Mediterranean show.

If it wanted to, Europe could improve

The confidence exuding from the booths set up by L’Oreal and LVMH at VivaTech this year – or maybe that was the perfume? – demonstrated how European companies can marry their unique heritage with the latest technologies, cementing their place as key global players. And the fractious politics of European integration can be overcome, as shown by the sweeping (but flawed) legislation on data protection that came into effect across the EU last year. I would like to think that Europe could harness the growing uncertainty about America’s trans-Atlantic security guarantees to invest serious cash in its own DARPA-equivalents.

Macron said Europe could become a tech leader by “building a tech ecosystem that is compatible with democracy.” This is shorthand for rules and regulations on data privacy, competition, and the like, carving out a middle ground between the libertarian free-for-all in the U.S. and the state-dominated model in China. I will address this in more detail in (another) TL;DR piece of mine on 5G, AI and the geopolitical battle that is in its early rounds.

Nobody doubts that France and the rest of the Europe have the raw material to create leading tech companies. On the final day of the VivaTech, which is open to the public, families flocked to the expo center: kids played with robots, waited eagerly in line for virtual reality demos, and took part in hackathons. The main stage featured a lively mock trial on the internet’s impact on democracy, and there were no empty seats at a workshop for women in tech.

I like Macron – yes, he has been a disappointment in many things – but I think his vision for France as a “startup nation” is not just talk. But fostering firms to grow beyond the startup stage requires a more concerted co-operation and integration between countries in Europe. That seems to go against the prevailing trends at the moment. And despite the politics of the day, the risk is that Europe will take the lead in regulating and taxing the digital economy, but remains relegated to a secondary role when it comes to building it.

Et … voilà

It was three-days well spent. And when you have a 4-person “information collection crew” to assist, the stress is off. For these technology events it is simply impossible to be a one-man-band.

Now … time to head out for some nice wine and a nice dinner with my crew.