With apologies to Caspar David Friedrich

and his “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog”

Some claim the world is gradually becoming united, that it will grow into a brotherly community as distances shrink and ideas are transmitted through the air. Alas, you must not believe that men can be united in this way. To consider freedom as directly dependent on the number of man’s requirements and the extent of their immediate satisfaction shows a twisted understanding of human nature, for such an interpretation only breeds in men a multitude of senseless, stupid desires and habits and endless preposterous inventions. People are more and more moved by envy now, by the desire to satisfy their material greed, and by vanity.

– Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (1880)

Some end-of-the-year thoughts from my book-in-progress “Data: it’s not the new oil, it’s the new asbestos”, my attempt to explain our “information apocalypse”

19 December 2018 – When FDR signed the U.S. Social Security Act into law in 1935, he created one of the most comprehensive information-gathering networks in America’s history. The nine-digit Social Security number — the first number to be assigned by the American government to individual citizens — tracked the amount of payroll tax workers paid over the course of their lives, information that was used to determine their eligibility for Social Security.

As a system of identification it was unprecedented in scope: it was more comprehensive than the draft and even the census, which collected information only in the aggregate. Yet Americans reacted to the news not with alarm but with enthusiasm. Many wore dog tags engraved with the number or bronze-plated it, while others, in the years before Americans knew much of the concentration camps, had their SSN tattooed on their bodies.

How times have changed. Today the undermining of basic trust in institutions and traditions has run amok. Somehow, things got turned on its head. If you look at its history, Silicon Valley grew out of a widespread cultural commitment to data-driven decision-making and logical thinking. Its culture was explicitly cosmopolitan and tolerant of difference and dissent. Both its market orientation and its labor force were (and still are) global. And Facebook … wow. It started with a strong missionary bent, one that preached the power of connectivity and the spread of knowledge to empower people to change their lives for the better.

So just how in hell how did one of the greatest Silicon Valley success stories end up hosting radical, nationalist, anti-Enlightenment movements that revolt against civic institutions and cosmopolitans? How did such an enlightened firm become complicit in the rise of nationalists such as Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Narendra Modi, Rodrigo Duterte … and ISIS? How did the mission go so wrong? Facebook is the paradigmatic distillation of the Silicon Valley ideology. No company better represents the dream of a fully connected planet “sharing” words, ideas, images, and plans. No company has better leveraged those ideas into wealth and influence. No company has contributed more to the paradoxical collapse of basic tenets of deliberation and democracy.

I had begun to focus on all of this back in 2015 when I viewed our public square: data, code and algorithms were driving our civil discourse. And then … the apocalypse noted in the previous paragraph. We no longer share one physical, common square, but instead we struggle to comprehend a world comprised of a billion “Truman shows”. It gave birth to my book.

And then there’s the Senate report this week on the extensive Russian operation to use social media to affect electoral campaigns and to deepen political and racial tensions in the United States. It just showed how dangerously uninformed and naive the U.S. (and most of the West) has been on Vladimir Putin’s deliberate strategy: to disrupt democracy and create chaos in the West. Using the West’s very own social media technology to do it. For the full report … which examined the data sets provided by Facebook, Google and Twitter, and Google … with all of its slides, infographics, and whitepaper … just click here.

Listen. None of this is “new”. As my good friend, Julia Ioffe (a Russian-born American journalist who covers national security and foreign policy topics for The Atlantic magazine) has pointed out, the history of Russian involvement and meddling in American society has been going on for 80-plus years.

It is all contributes to the central tenent of my book:

No country has come close to the U.S. in harnessing the power of computer networks to create and share knowledge, produce economic goods, intermesh private and government computing infrastructure including telecommunications and wireless networks, using all manner of technologies to carry data and multimedia communications, and control all manner of systems for our power energy distribution, transportation, manufacturing, etc. … and so left the U.S. the most vulnerable technology ecosystem to those who can steal, corrupt, harm, and destroy public and private assets, at a pace often found unfathomable.

Let me try and unpack some of this, a collection os somewhat random thoughts pulled from my research.

It’s about advertising, stupid

For the last 20 years, every consumer-oriented application, service or content platform has used “ads” as its default business model. Like always, the road to hell has been paved with good intentions: we assumed that the mostly innocuous billboards could be transposed to the web… but these banner ads quickly became endless trojan horses into our privacy, feelings and opinions. Our naive “content-wants-to-be-free” approach failed to account for externalities, including the fact that hostile organizations are influencing us through our media consumption.

The seeds of Facebook were planted in 1915 with John Watson, president of the American Psychological Association. He argued that all human behavior was essentially the product of measurable external stimuli and could therefore be understood and controlled through study and experiment. This approach became known as “behaviorism”, and it was later popularized further by the work of B. F. Skinner. As you can imagine, the promise of malleable humans was catnip to companies hoping to sell products, and behaviorism spread through the corporate world like a virus.

Then in the 1920s along came statistical market research (which, unlike behaviorism, actually required asking people questions). Taken together, behaviorism and market research signaled a more scientific approach to advertising that has been with us ever since and transformed our entire culture.

So much of the current debate … the damage that large technology companies are causing to parts of the economy, the social fabric of society and democracy … comes back to that foundation on which most media organizations were built: advertising. We surrendered all of this to be driven by advertising. That is where you need to start. And, honestly, if you wanted to build a machine that would distribute propaganda to millions of people, distract them from important issues, energize hatred and bigotry, erode social trust, undermine respectable journalism, foster doubts about science, and engage in massive surveillance all at once, you would make something a lot like Facebook.

Of course, none of that was part of the plan. But those of us who have studied or followed the rise of authoritarianism and the alarming erosion of democracy around the world would by 2018 list India, Indonesia, Kenya, Poland, Hungary, and the United States as sites of Facebook’s direct contribution to violent ethnic and religious nationalism, the rise of authoritarian leaders, and a sort of mediated cacophony that would hinder public deliberation about important issues, thus undermining trust in institutions and experts. Somehow, Zuckerberg missed all of that.

But the point is telling because the structure and function of Facebook work powerfully in the service of motivation. If you want to summon people to a cause, solicit donations, urge people to vote for a candidate, or sell a product, few media technologies would serve you better than Facebook does. Yep. Facebook is great for motivation. But terrible for deliberation.

And that is the crux of the entire debate. When we combine the phenomena of propaganda with filter bubbles, we can see the toxic mixture that emerges: Facebook users are incapable of engaging with each other upon a shared body of accepted truths. But all social media contributes to this. Many of us are more likely not to find the debunking claim after we see the disinformation story it is debunking. Arguments among differently minded users often devolve into disputes over what is or isn’t true. It’s usually impossible within the Facebook platform to drive a conversation beyond sputtering contradictions.

So filter bubbles distance us from those who differ from us or generally disagree with us, while the bias toward sensationalism and propagandistic content undermines trust. In these ways social media makes it harder for diverse groups of people to gather to conduct calm, informed, productive conversations. Deliberation has died.

It’s the engineering, stupid

To be an informed citizen is a daunting task. To try and understand the digital technologies associated with Silicon Valley — social media platforms, big data, mobile technology and artificial intelligence that are increasingly dominating economic, political and social life – has been an even more daunting task that brought me to interview scores of advertising mavens, data scientists, data engineers, psychologists, etc. Plus reading reams of white papers and books tracking the evolving thinking and development of this technology. I needed to dust off some classic tomes that have been sitting in my library for years, from authors such as James Beniger, Marshall McLuhan and Alvin Toffler … all of them so prescient in where technology would lead us, their predictions spot on to where we are today.

And what you really come away with after reading these chaps a third time through is that this big “Information Society” we think is so new is not so much the result of any recent social change … information has always been key to every society … but due to the increases begun more than a century ago in the speed of material processing. Microprocessor and computer technologies, contrary to currently fashionable opinion, are not new forces only recently unleashed upon an unprepared society, but merely the latest installments in continuing development. It is the material effect of computational power that has put us in a tizzy.

Markets have always been predicated on the possession and exchange of information about goods and the condition of their availability. But what’s different this time is that with the introduction of digital technologies and the ubiquitous status they have attained, information has become the basic unit of the global economy.

But it was Neil Postman, the legendary public intellectual who had emerged as the earliest and most vocal scold of all that is revolutionary, that nailed it as far as the future Facebook. He had written the 1985 bestseller Amusing Ourselves to Death, about the ways that television had deadened our public discourse by sucking all modes of deliberation into a form defined by the limitations of entertainment. He would go on a decade later to raise concerns about our rush to wire every computer in the world together without concern for the side effects, and the “social information connection implications”.

All these books I well remember. I am a Baby Boomer (age 67) so I rode the optimistic waves of the post–Cold War 1990s. The U.S. was ascendant in the world, leading with its values of freedom, ingenuity, and grit. Crime was ebbing. Employment was booming. I was a fellow traveler in a movement that seemed to promise the full democratization of the Enlightenment. Digital technology really seemed to offer a solution to the scarcity of knowledge and the barriers to entry for expression that had held so much of the world under tarps of tyranny and ignorance. I remember those old computers, some of those early “laptops”. If you ran those things for too long it would get hot enough to double as a toaster.

Facebook knew how to explicitly engineer itself to promote items that generate strong reactions. If you want to pollute Facebook with nonsense to distract or propaganda to motivate, it’s far too easy. The first step is to choose the most extreme, polarizing message and image. Extremism will generate both positive and negative reactions, or “engagements.” Facebook measures engagement by the number of clicks, “likes,” shares, and comments. This design feature — or flaw, if you care about the quality of knowledge and debate — ensures that the most inflammatory material will travel the farthest and the fastest. Sober, measured accounts of the world have no chance on Facebook. And when Facebook dominates our sense of the world and our social circles, we all potentially become carriers of extremist nonsense.

In the end we became governed by an ideology that saw computer code as the universal solvent for all human problems. And an indictment of how social media has fostered the deterioration of democratic and intellectual culture around the world.

Control is not the issue, stupid

So how did regulators react? With such things as the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) … a half-hearted attempt to “save the day”. At almost every technology event (at least the legal technology ones) everyone emphasizes that “control” of personal data is the core to privacy. The need for data minimization. For technology vendors, catnip once again. Easy concepts to understand. Easy to sell “solutions”. Easy tech to explain.

But control is the wrong goal for “privacy by design” (the “new new” thing at most data conferences), and perhaps the wrong goal for data protection in general. Too much zeal for control dilutes efforts to design information protection correctly. This idealized idea of control is impossible. Control is illusory. It’s a shell game. It’s mediated and engineered to produce a particular control. If you are going to focus on anything, design is everything. The essence of design is to nudge us into choices. Asking companies to engineer user control incentivizes self-dealing at the margins. Even when good intentioned, companies ultimately act in their own self interests. Even if there were some kind of perfected control interface, there is still a mind-boggling number of companies with which users have to interact. We have an information economy that relies on the flow of information across multiple contexts. How could you meaningful control all those relationships?

I did not have time to fully analyse the story that broke last night via the New York Times that internal documents show that Facebook gave Microsoft, Amazon, Spotify and others far greater access to people’s data than it has disclosed. But it shows we can no longer comprehend the complexities involved in data sharing. Whatever you give to Facebook is in the public domain forever. Yes, arguments will be made that GDPR violations apply. But it is going to be a case of lawyers playing wack-a-mole as your data is perpetually traded, exchanged, sold and saved discretely by many.

To see why data ownership is a flawed concept, first think about this post youʼre reading. The very act of opening it on an electronic device created data — an entry in your browserʼs history, cookies the website sent to your browser, an entry in the websiteʼs server log to record a visit from your IP address. Itʼs virtually impossible to do anything online – reading, shopping, or even just going somewhere with an internet-connected phone in your pocket – without leaving a “digital shadow” behind. These shadows cannot be owned – the way you own, say, a bicycle – any more than can the ephemeral patches of shade that follow you around on sunny days.

Your data on its own is not very useful to a marketer or an insurer. Analyzed in conjunction with similar data from thousands of other people, however, it feeds algorithms and bucketize you (e.g., “heavy smoker with a drink habit” or “healthy runner, always on time”). If an algorithm is unfair – if, for example, it wrongly classifies you as a health risk because it was trained on a skewed data set or simply because youʼre an outlier – then letting you “own” your data wonʼt make it fair. The only way to avoid being affected by the algorithm would be to never, ever give anyone access to your data. But even if you tried to hoard data that pertains to you, corporations and governments with access to large amounts of data about other people could use that data to make inferences about you.

And that get’s to my main point. “Controlling” data such as age, gender, race, health, and sensitive terms is impossible. It is why these talking heads miss the whole point, especially as regards the Internet of Things (IoT). The IoT is not about security/cyber issues. It is about inference from the stream of data IoT produces. So that AI systems can reconstruct any term they want or need from high-dimensional inputs, plugging all of this information into algorithmic social media analysis to identify, in a split second, sexual preference, political leanings, and income level.

The GDPR was meant to protect people’s privacy, identity, reputation, and autonomy, but it will fail to protect data subjects from the novel risks of inferential analytics (which I will discuss in much more detail next month at the International Cyber Security Forum in Lille, France plus a long blog post).

So when control is the “north star” then lawmakers aren’t left with much to work with. It’s not clear that more control and more choices are actually going to help us. What is the end game we’re actually hoping for with control? If data processing is so dangerous that we need these complicated controls, maybe we should just not allow the processing at all? How about that idea? Anybody? Bueller? Bueller?

Had regulators really wanted to help they would have stopped forcing complex control burdens on citizens, and made real rules that mandate deletion or forbid collection in the first place for high risk activities. But they could not. They lost control of the narrative. As soon as the new GDPR negotiations were in process 3+ years ago the Silicon Valley elves send their army of lawyers and lobbyists to control the narrative to be about “control” burdens on citizens. The regulators had their chance but they got played. Because despite all the sound and fury, the implication of fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy is that individuals would control and manage their own data and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies know it is too late now to impose that structure so they will make sure any new laws that seek to redress any errors work in their favor.

And down deep we really do not care. The barrage of privacy notices we receive has become like all the disregarded warnings about the dangers of trans-fats and corn syrup. We want to be healthy, but we like doughnuts more. The greatest security problem we will always have is human nature. Technology will continue to make the benefits of sharing our data practically irresistible. Utility always wine. And now we have digital assistants like Amazon’s Echo and Google Home listening to every word and sound in the home and people are buying them by the millions. Next year Amazon Echo will reveal sound analysis that can detect somebody eating a potato chip. Oh, what fun to come!

The fascinating work of researchers like Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and Dan Ariely has demonstrated how terrible human beings can be at thinking logically, unemotionally. For all the immense power of the human mind, it is very easy to fool. I’m a firm believer in the power of human intuition and how we must cultivate it by relying on it, but I cannot deny that my faith has been obliterated by reading books like Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow and Ariely’s Predictably Irrational. After reading their work, you might wonder how we survive at all.

And we might actually need to thank the French

I recently wrote about the “Vectaury” decision from the Commission nationale de l’informatique et des libertés (CNIL), the independent French administrative regulatory body whose mission is to ensure that data privacy law is applied to the collection, storage, and use of personal data. It is a very thorough analysis regarding the GDPR compliance of a relatively unknown French adtech company named “Vectaury”.

My post was written for my advertising/media listserv for which I write material addressing the online advertising ecosystem. The case is in French, and my analysis is in French, but over the Xmas holidays I will put the decision and my analysis in English and next month I will distribute to my e-discovery listserv.

In brief, the case fine-wise is small fry, but the decision has potential wide-ranging impacts for Facebook, Google, and today’s entire EU adtech industry. Vectaury was collecting geolocation data in order to create profiles (eg. people who often go to this or that type of shop) so as to do “power ad targeting”. They operate through embedded SDKs and ad bidding, making them invisible to users.

What is most intriguing about the case is that CNIL notes that profiling based off geolocation presents particular risks since it reveals people’s movements and habits. They said that process requires consent — and that is at the heart of its analysis. Interesting point: they justified their decision in part because of how many people COULD be targeted in this way rather than how many actually were, although they note that, too, in the decision. And because it’s on a phone, and we all have phones, it is considered large-scale processing no matter what.

One other key factor: the technicity and opacity of ad bidding systems is used to justify greater transparency requirements. People cannot expect to consent to what they don’t understand (or even know exist), therefore the adtech ecosystem is de facto under *stronger* requirements.

The decision also notes CNIL is openly using this to inform not just the company in question but whole ecosystem, including adtech of course but also app makers who embed ads and marketers who use them. So … everybody is on notice. More next month.

The real Facebook problem

And the problem is much bigger and broader than what happens to our Facebook data. Through its destructive influence on other media firms, industries, and institutions, Facebook undermines their ability to support healthy public deliberation as well. Facebook distorts the very sources of news and information on which a democratic republic relies. On the one hand, Facebook is rapidly draining away advertising revenue from responsible and reputable news sources. If a firm has a small advertising budget, it is likely to shift spending toward targeted, accountable advertising systems such as Facebook and Google and away from display ads that offer no way to measure user engagement. As I will demonstrate in a post next month, the GDPR has actually strengthened the Facebook/Google duopoly, not weakened it.

And side note: for all this talk by the major European telecoms saying “Europe is moving in the right direction” and “we are unique in the way Europe is protecting the data of its citizens” and the Silicon Valley companies creating “competitive asymmetries”, what happens? Orange announced a partnership with Amazon to develop a smart speaker called Djingo in France. And although Orange has the capability, it handed off search queries to, er, Amazon.

Well done, Orange. Nothing says “socking it to GAFA” [Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple] quite like teaming up with GAFA. But look. The telecoms are screwed. They can look only as far as they can purchase. They can talk the talk, but they cannot “R&D the walk”, especially to the required scale. They can only shop it at which point the only ones which can offer them a solution, which can scale to any degree necessary, which have the R&D firepower, are the GAFA +/-M (Microsoft).

And while I am on a roll, a word on Tim Cook. He was the keynote speaker at the 2018 International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners in Brussels, which I attended. He made headlines with his “data industrial complex” speech (a long-standing favorite phrase of his) and joined the chorus of voices about the need to stop the “trade in digital data, these scraps of data, each one harmless enough on its own, assembled, synthesized, traded and sold”. Plus his support for a “U.S. GDPR”.

Apple’s effort can easily be cynically dismissed when confronted with the fact that Apple sells $12Bn worth of “search users” to Google every year. Google reportedly paid Apple $9 billion in 2018 and will pay Apple $12 billion in 2019 to remain as Safari’s default search engine. Goldman Sachs analyst Rod Hall (who covers all of this stuff) noted “it seems like a hefty price to pay, but with Safari being the default browser on iPhone, iPads, and Macs — and Google continuing to generate a great deal of revenue from its original search engine business — the payments to Apple are a fraction of the money it ends up making. Apple is one of the biggest channels of traffic/data acquisition for Google. You know, that thing Tim Cook bitched about: data being assembled, synthesized, traded and sold.

Facebook has grown so adept at targeting ads and generating attention that advertising companies design entire campaigns around the “viral” potential of their messages. As reputable news organizations lay off reporters and pay less for freelance work, they have altered their editorial decisions and strategies to pander to the biases inherent in Facebook’s algorithms. Editors and publishers spend much of their working days trying to design their content to take flight on Facebook. They have to pander to the very source of their demise just to hold on to the audiences and the potential for a sliver of the revenue they used to make. Facebook has invited publications to join into partnerships in which Facebook’s servers deliver the content has only marginally slowed the decline of revenues for those publications while encouraging them to design their content to echo among Facebook users. Facebook is feeding our worst appetites while starving the institutions that could strengthen us.

How Google tracks you

One of the more eye opening presentations this past year was a GDPR workshop put on by the Max Planck Institute in Vienna, Austria which explained … in incredible detail … how Google builds a digital profile on just about everybody. The presenters were two ex-Google Analytics analysts. The following is a mashup of those presentations and includes some detailed slides I have converted to narrative.

Today, 40,000 Google search queries are conducted every second. Thatʼs 3.5 billion searches per day, 1.2 trillion searches per year. When you search on Google, your query travels to a data center, where up to 1,000 computers work together to retrieve the results and send them back to you. This whole process usually happens in less than one-fifth of a second.

Most people donʼt realize that while this is going on, an even faster and more mysterious process is happening behind the scenes: an auction is taking place. For as long as you’ve been using Google, Google has been building a “citizen profile” on you. Every internet search contains keywords, and the keywords you just entered into Google are fought over by advertisers. Each advertiser who offers a product related to your keywords wants its ad to be seen and clicked.

Then, like those cartoon toys in Toy Story scrambling to get back in the right order before their owner throws on the light, the ads finalize their positions before your customized results page loads on your screen. Generally, your first four search results – what you see before having to scroll down—are all paid advertisements. Once you click on an ad, your information passes through to search engine marketers, where itʼs forever stored in an AdWords account, never to be erased.

Here is a complete checklist of everything Google knows about you (or tries to know about you) as December 2018:

-Your age

-Your income

-Your gender

-Your parental status

-Your relationship status

-Your browsing history (long-term and short-term)

-Your device (phone, tablet, desktop, TV)

-Your physical location

-The age of your child (toddler, infant, etc.)

-How well you did in high school

-The degree you hold

-The time (of day) of your Google usage

-The language you speak

-Whether youʼve just had a major life event

-Your home ownership status

-Your mobile carrier

-The exact words you enter into Google search

-The context and topics of the websites you visit

-The products you buy

-The products you have almost bought

-Your Wi-Fi type

-Your proximity to a cell tower

-Your app installation history

-The amount of time you spend on certain apps

-Your operating system

-The contents of your email

-The time you spend on certain websites

-Whether youʼre moving (e.g., into a new home)

-Whether youʼre moving (e.g., walking or on a train)

For as long as youʼve been using Google, Google has been building a “citizen profile” on you. This profile contains:

-Your voice search history

-Every Google search youʼve ever made

-Every ad youʼve ever seen or clicked on

-Every place youʼve been in the last year

-Every image youʼve ever saved

-Every email youʼve ever sent

In 2019, we will be coming close to realizing the Holy Grail of search engine marketing: multi device attribution. When this tech is realized, ads will follow searchers seamlessly—not only across channels (e.g. social, organic, and email) but across devices (e.g., from mobile to tablet to laptop to TV to desktop).

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

Apple has now shipped the EKG heart monitor app for the new Watch. We get blasé about this stuff so quickly, but it’s still amazing that the latest version of a mainstream consumer product with tens of millions of users might now alert you to a life-threatening heart condition. It’s incredible.

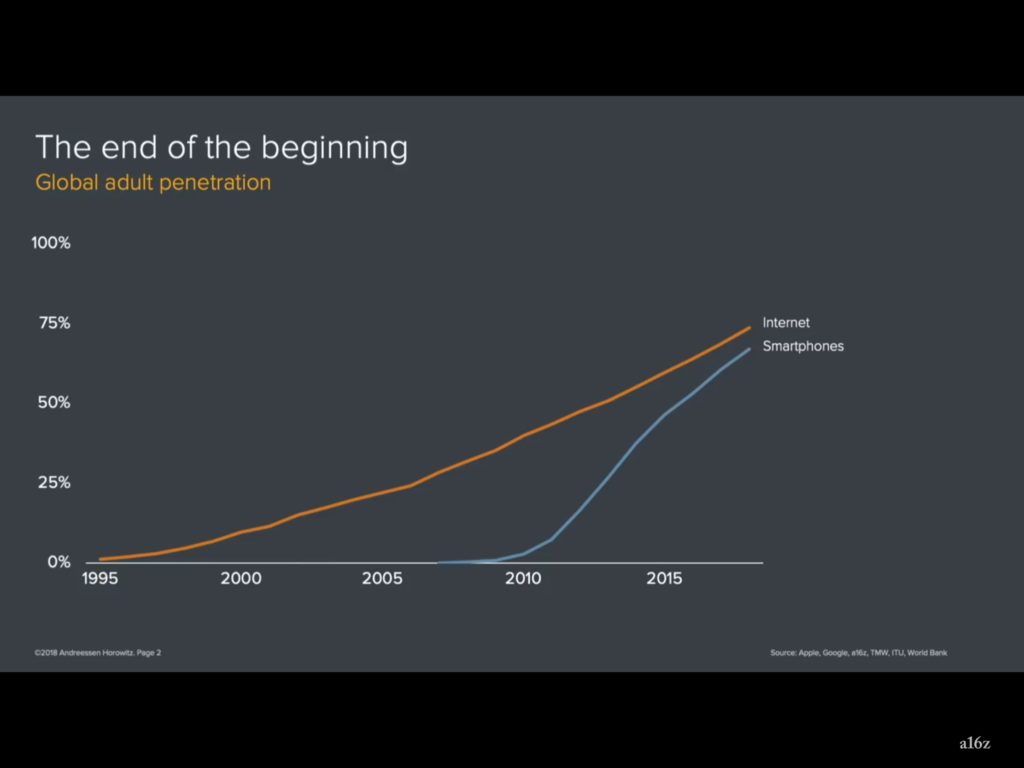

I thought about this when I saw this slide at a Ben Evans presentation:

His point was this was a good way of thinking about where we are today – a talk about the end of the beginning. Because it struck me that we’ve been looking at charts like this for most of the last 20 years. They always go up and to the right. And now we’re getting to the point where we are kind of finishing now. The axis story is reaching the end. Because we’ve connected three quarters of people on earth and we’ll connect all of the rest.

But as we go forward, the other part of the story isn’t close to being finished. The axis story is finished but the use story (like Apple) is just starting to begin. And it feels like that is what the next twenty years will be about. We’ve spent the last ten years talking about and building stuff on social and on search. Now we think about machine learning and we think about building things on crypto currencies. And so I got into this I realized what 2018 was all about: market sizes.

That’s my lead for my first post which will start 2019: 52 Little (and Big) Things I Learned About Technology: a look back at 2018.

Have a Merry Xmas and Happy New Year … or whatever heathen holiday you follow.