The artist’s signature?

5 November 2018 (Paris, France) — Creating works using artificial intelligence have very important implications for copyright law. I have been fortunate to be involved in two current cases that have required my deep dive into the issues.

Robotic artists have been involved in various types of creative works for a long time. Since the 1970s computers have been producing crude works of art, and these efforts continue today. Most of these computer-generated works of art relied heavily on the creative input of the programmer; the machine was at most an instrument or a tool very much like a brush or canvas.

But today, we are in the throes of a technological revolution that may require us to rethink the interaction between computers and the creative process. That revolution is underpinned by the rapid development of machine learning software, a subset of artificial intelligence that produces autonomous systems that are capable of learning without being specifically programmed by a human.

A computer program developed for machine learning purposes has a built-in algorithm that allows it to learn from data input, and to evolve and make future decisions that may be either directed or independent. When applied to art, music and literary works, machine learning algorithms are actually learning from input provided by programmers. They learn from these data to generate a new piece of work, making independent decisions throughout the process to determine what the new work looks like. An important feature for this type of artificial intelligence is that while programmers can set parameters, the work is actually generated by the computer program itself – referred to as a neural network – in a process akin to the thought processes of humans.

Over the last century, the subject-matter of copyright has seen an expansion as the proliferation of information has created “new” subject matter capable of protection with the justifications for protection aligning more with traditional economic rationales of copyright and IP systems. So what happens when a “modern” technology such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) meets a field more closely associated with the romantic (big and little “R”) notions of copyright?

Two weeks ago (on 26 October) we had a story from New York which shed some light on these issues. Alexander de Leeuw at the Dutch IP firm Brinkhof noted on his blog last week:

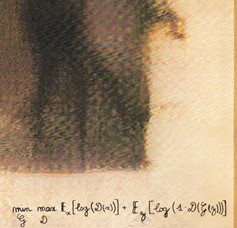

Last Friday (26 October) was a remarkable day in the history of art sales. For the first time a painting made entirely using ‘Artificial Intelligence’ was sold at auctioning house Christie’s New York. The painting with the title “Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy” was originally estimated at $7,000-$10,000 but ultimately sold for the staggering amount of $432,500 (including fees). Much like a painting of human origin, the painting sold at Christie’s was signed by “the artist” with a core component of the algorithm that created it:“min G max D Ex[log(D(x))]+Ez[log(1-D(G(z))]”.

So how did this portrait of the imaginary Edmond de Belamy (the full painting at the top of this post, with a close-up of the signature) come into existence? It essentially comes down to teaching a computer how to paint. The portrait was made with machine learning algorithms called Generative Adversarial Networks (“GANs”). In brief, these algorithms are capable of generating images by mimicking characteristics of images from a training dataset (but are also capable of generating other output such as music and text). The artist Pierre Fautrel of the Paris-based art collective Obvious Art (which includes Hugo Caselles-Dupré who I will quote below) inserted 15,000 portraits dating from the 14th to the 20th century into the software, enabling it to make portraits itself. This led to a series of eleven unique images portraying the ‘Belamy family’, of which Edmond de Belamy is one.

The sale of Edmond de Belamy raises fundamental questions as to how centuries of IP law will interact with AI, the obvious question being whether there can be copyright in an AI-created portrait. Visually these paintings can hardly (if at all) be distinguished from paintings of human origin, supporting the view that if copyright protects expression (as opposed to an idea), there is an artistic expression to some extent. On the one hand, the AI can be seen as a tool used by a human artist. On the other hand, one could argue that the AI itself is emulating creativity, not the person feeding data to the machine.

But is that enough, or even relevant for copyright law’s purposes? Even assuming there can be copyright protection, a fierce debate can be held over who is the author and, therefore, who owns it. Is it Pierre Fautrel, who used the software to create the series of paintings and selected the paintings for the dataset, or are we in the realms of joint ownership with the creator of the algorithms? These questions will become more difficult to answer with the increasing potential of independently operating AI systems particularly if AI datasets are pulling from open source material.

The answers to these questions can have far reaching implications, from everyday issues such as whether Edmond de Belamy can be freely copied by others, to more peculiar questions, for example, with respect to the droit de suite. With the fast-paced development of AI algorithms, their broad applicability, and the recent high-value auction of Edmond de Belamy, these questions will have to be answered. National courts are likely to grapple with these questions sooner rather than later.

One of the cases with which I am involved is in Holland. Under Dutch law there is a rather low threshold for obtaining copyright protection. Hence, if presented in front of a Dutch court, copyright protection would likely be afforded as long as human choices – such as feeding specific information to the software – are involved. Even if no human choices are involved other than in creating the software, for example by connecting the software to Google images for its data input, copyright protection would likely be afforded to the person who wrote the software, both for the software and the resulting painting.

A distinct IP question is what are people paying for when buying AI paintings? In legal terms they are buying a physical object. To the extent that any copyright exists (which may differ from territory to territory) they may also be getting an implicit or implied license. However, not all purchase agreements provide much clarity on what rights the buyer is getting. It is questionable whether amounts in the range of $432,500 would be paid for non-exclusive AI paintings. Which creates a fun question as to whether, when Christie’s delivers your painting, they also give you a hard drive with the code.

A more policy driven question also needs to be answered: Why are buyers willing to pay so much for AI art? Is it the concept of buying a new – and currently still rather unique – form of art? In other words, is this a “first time value”? Or are people paying for the actual (artistic?) expression of the algorithms?

Perhaps the answer to that last question may answer whether copyright should protect such works and which part of the subject-matter. If emotion has little to do with so many protectable works now, then why treat AI any differently? Does it matter that this form of AI algorithm is using data sets to imitate previous work in creating a new work (i.e. GAN), as opposed to the CAN (Creative Adversarial Networks) system at Rutgers which is using data sets to create novel works – something different than the data? Or are different AI systems just doing what artists have done for centuries – imitating and breaking the mold?

On the final question of authorship, Caselles-Dupre explained that:

If the artist is the one that creates the image, then that would be the machine. If the artist is the one that holds the vision and wants to share the message, then that would be us.

And therein lies the problem. Traditionally, the ownership of copyright in computer-generated works was not in question because the program was merely a tool that supported the creative process, very much like a pen and paper. Creative works qualify for copyright protection if they are original, with most definitions of originality requiring a human author. Most jurisdictions, including Spain and Germany, state that only works created by a human can be protected by copyright.

But with the latest types of artificial intelligence, the computer program is no longer a tool; it actually makes many of the decisions involved in the creative process without human intervention. One could argue that this distinction is not important, but the manner in which the law tackles new types of machine-driven creativity is going to have far-reaching commercial implications. This leaves open the question of who the law would consider to be the person making the arrangements for the work to be generated. Should the law recognize the contribution of the programmer or the user of that program?

Monumental advances in computing and the sheer amount of available computational power may well make the distinction moot; when you give a machine the capacity to learn styles from large datasets of content, it will become ever better at mimicking humans. And given enough computing power, soon we may not be able to distinguish between human-generated and machine-generated content.

We are not yet at that stage, but if and when we do get there, we will have to decide what type of protection, if any, we should give to emergent works created by intelligent algorithms with little or no human intervention. Although copyright laws have been moving away from originality standards that reward skill, labour and effort, perhaps we can establish an exception to that trend when it comes to the fruits of sophisticated artificial intelligence. The alternative seems contrary to the justifications for protecting creative works in the first place.