Data privacy? Legislate … then add water.

But there are issues far beyond data privacy.

25 October 2018 (Brussels, Belgium) — If the millions (hyperbole alert) of insufferable think pieces, conference presentations, and webinars on the topic are any indication, protecting personal data is a pretty good idea. And that creaking old EU just may have achieved something useful for the world.

So there we all were yesterday at the 40th International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners (ICDPPC) as top executives from Facebook, Google and Apple heaped praise on Europe’s revamped data protection standards … just as these companies face ever tighter scrutiny over privacy and the prospect of similar restrictions in the United States.

NOTE: the ICDPPC is considered to be the premier global forum for data protection authorities at the international level of data protection and privacy. There are 119 privacy and data protection authorities from across the globe. The closed sessions of the conference took place on Monday and Tuesday, open only to accredited members and observers of the ICDPPC. The public sessions took place yesterday and today, the 24 and 25 October. The public session is open to all.

Apple’s Tim Cook received the most attention .. he was the only U.S. CEO to appear in person .. as he spoke in the strongest terms, calling for a federal U.S. privacy law to match Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, and warning about the rise of a “data industrial complex” that would work against regular people:

Our own information, from the everyday to the deeply personal, is being weaponized against us with military efficiency.

He said nothing new. “Data industrial complex” is a phrase he has used before. The entire speech was pretty much the mantra he has repeated at many conferences and press interviews these last few years. The only difference this time was he had a better stage, was louder … and got better press coverage. Appearing via video links, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Sundar Pichai also heralded the advent of privacy legislation, though in less explicit terms, while acknowledging the challenge of “getting privacy right” on their global platforms. And Mark repeated that chestnut from his U.S. Congressional testimony and UK Parliament testimony:

“If people don’t trust us, then they won’t use us”

Yet all of this show of support for Europe’s privacy law conceals vast differences in how the United States and Europe conceive of privacy, as well as between many of Silicon Valley’s biggest names. Cook’s warning about the “data industrial complex” and calls for U.S. laws was far more pointed than statements from the Facebook or Google bosses, whose business models largely rest on harvesting vast amounts of personal data. Even Noah Phillips, a U.S. federal trade commissioner, who attended the event acknowledged that the onset of Europe’s new privacy standards has triggered a debate about privacy in the United States:

“GDPR has certainly had an impact on the national conversation in the U.S. It’s as robust a conversation we’ve had on this issue certainly for a long time. But changes in European law doesn’t change the pressure on the FTC, or what privacy rules should apply in the U.S. Getting privacy right requires careful consideration of the hard issues that come up every day”

Cue up the lobbyists.

To many in the audience … industry watchers and data protection campaigners alike … there was a question about the firms’ motivations, and how real their concerns. Not mentioned? The series of privacy scandals over the last three to four years concerning Facebook and Google and the continuing myriad U.S. investigations into data privacy violations and other misuses of personal data across a wide spectrum.

Legislate, then add water

While tech executives promoted their privacy credentials, industry watchers and data protection campaigners questioned the firms’ motivations amid a growing regulatory push worldwide to pass new legislation. A year ago, their playbook was self-regulation. But now, they want a federal law … that is weak. Having seen how GDPR was watered down … and many of them helped to water it down … these tech companies certainly see another opportunity to control the narrative in their favor.

Because despite all the sound and fury yesterday, the implication of fully functioning privacy in a digital democracy is that individuals would control and manage their own data and organizations would have to request access to that data. Not the other way around. But the tech companies know it is too late to impose that structure so they will make sure any new laws that seek to redress that issue work in their favor.

And so we have dear Tim saying companies must should challenge themselves to de-identify customer data or not collect that data in the first place. Or if that fails (which it will) allowing users to know what data is being collected from them and what it’s being collected for. And at least get a copy of their personal data. Better to put the burden on the consumer, the user. Heaven forbid we stop the collection of data in the first place.

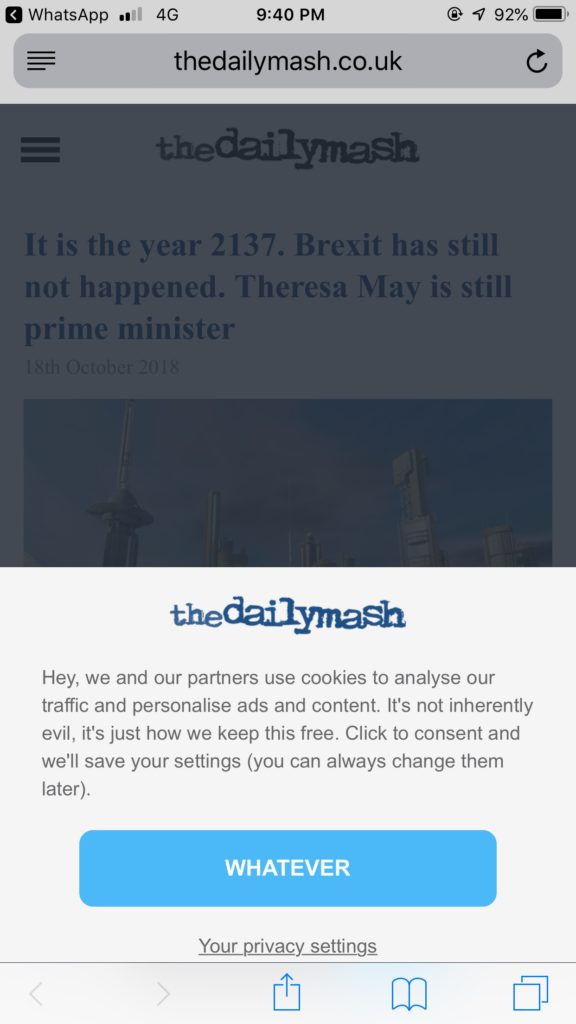

Hey, I know! We could have “opt in” and “opt out”. Then we could have the same pop up screens being used with GDPR:

For firms like Facebook and Google, ensuring ongoing access to data remains key amid the global overhaul of data protection standards. Amid this privacy push, some tech companies are quickly changing their tune, with some advocates warning that these firms are now in favor of new legislation … so that they can, as I noted, lobby to water it down as much as possible. Not surprisingly, tech company officials disagree. They claim that their existing privacy standards offer people sufficient protections, and that by collecting individuals’ information to power online advertising, they can offer users free services that otherwise would not be available.

But the really big issues are not even privacy related

What’s complicating the debate, though, is that different tech companies often have contradictory goals, depending on their business models. For firms like Facebook and Google, ensuring ongoing access to data — even with greater privacy protection for their users — remains key amid the global overhaul of data protection standards. But for companies like Apple, whose main income generator is selling smartphones and other digital devices rather than collecting people’s information, stronger data protection rules would not affect their underlying business.

But companies like Facebook can never be trusted. One example: barely waiting until the door had closed on the Instagram founders who fled the company last month, earlier this month Facebook began trialing misuse of Instagram location data to power ever-more targeted ads. This company is a cancer.

In short: Instagram was spotted prototyping a new privacy setting that would allow it to share your location history with Facebook. That means your exact GPS coordinates collected by Instagram, even when you’re not using the app, would help Facebook to target you with ads and recommend you relevant content. The geo-tagged data would appear to users in their Facebook Profile’s Activity Log, which include creepy daily maps of the places you been. It was something the founders of Instagram did not want to do.

This commingling of data has upset users who want to limit Facebook’s surveillance of their lives. With Facebook installing its former VP of News Feed and close friend of Mark Zuckerberg, Adam Mosseri, as the head of Instagram, most privacy watchers say Facebook would attempt to squeeze more value out of Instagram. That includes driving referral traffic to the main app via spammy notifications, inserting additional ads, or pulling in more data.

NOTE: if you recall, last May Facebook was sued for breaking that very promise to European regulators: that it would not commingle WhatsApp and Facebook data, leading to an $122 million fine. Its revenue in one day (yawn). It still commingles WhatsApp and Facebook data.

Some of this was discussed by Barry Lynn who gave a presentation yesterday afternoon at ICDPPC. Barry directs the Open Markets Institute which uses journalism to promote greater awareness of the political and economic dangers of monopolization, and he has written extensively about social media and monopoly power.

He discussed issues far beyond data protection. He noted that after Europe’s top monopoly buster Margrethe Vestager fined Google more than $5bn for abusing its dominance over mobile phone technology, one could hear “Hurrah!” across the land. It was tempting to relax about the power of big tech. We all felt “Not only is there a cop watching these giants, she’s carrying a really big stick!!”

But lost in all of that is the condition of journalism. At the same time as the Vestager decision, the firing by the New York Daily News of half the paper’s staff shines a different light on the matter. The reason given by the publisher – a sharp decline in revenue – is largely the result of Google abusing its monopoly over online advertising, in tandem with Facebook. Vestager’s move against Android does nothing to protect the free press in Europe or America: “This means it’s time for other regulators and legislators in America and in Europe to speed the process of bringing Google to heel”. Wishful thinking on his part.

To be sure, the decision by Europe’s Directorate General for Competition (DG Comp) is important. The fat fine was the clearest statement yet that Google’s practices break the law. Further, the restrictions DG Comp imposed on Google’s business model may … may … crimp its behavior in key ways. Vestager and her team do deserve thanks. Given the political power of Google, their actions took courage.

But it’s vital to put the fine into perspective, Barry says. In an industry that changes by the day, the case took eight years to complete. Further, it deals with just one part of a problem that is now very large and sprawling. And even after the fine Google will be left holding more than $100bn in cash: “Vestager’s fighters put out the fire on the first floor, but only after the blaze had spread to the rest of the building”.

As I have written before, perhaps of all the social goods now in flames the one we must protect first is trustworthy journalism. In the nine years since Google bought the mobile ad company AdMob, annual ad revenue at Google and Facebook has soared, to more than $95bn and almost $40bn, respectively. During this period, ad revenue at newspapers fell around $50bn in 2005 to under $20bn today.

The number of people working in America’s newsrooms dropped from more than 400,000 in 2001 to fewer than 185,000 today. This means fewer reporters on the streets. In New York, the picture is especially bleak. The number of reporters at the Daily News is nearly 90% below 1988 levels. The New York Times cut local reporting staff by more than half over the last decade, from 90 to 40.

I don’t think it is because citizens don’t want news. Especially since the election of Donald Trump, many new readers have bought subscriptions to national outlets like the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Some upstarts, like BuzzFeed, have also managed to stay ahead of the sword.

But Google and Facebook pose fundamental dangers to even the most successful outlets. Their status as essential gatekeepers to the news – some 93% of Americans get news online, with most getting it through Google and Facebook – gives these two the power to steer readers away from any newspaper, almost at will. Nicholas Thompson, editor-in-chief of Wired, said it best at a recent journalism/social media conference … describing the problem in stark terms:

Journalists know that the man who owns the farm has the leverage. If Facebook wanted to, it could quietly turn any number of dials that would harm a publisher – by manipulating its traffic, its ad network or its readers. And it does so. Unimpeded.

In the past, Americans carefully neutralized the monopoly powers of such behemoths. They made it against the law for these corporations to discriminate for or against any sender of information. They prevented them from competing with the companies – including newspapers – who rely on them to get to market. And such thinking remains very much alive today. The Federal Communication Commission’s “net neutrality” decision in 2015 applied non-discrimination rules to broadband and cable operators. The Microsoft case of the late 1990s aimed to prevent the conflicts of interest that come from “vertical integration”.

I did not intend to run off the page on antitrust issues. But just a few points. Existing regulatory tools fail to address the risks posed by these monster firms. Antitrust laws prohibit certain kinds of anticompetitive behavior. Companies can be fined for fixing prices or bundling products together to stifle competition. But such laws do not regulate market power directly; these “superstar firms” operating data-rich markets can exercise a dangerous degree of control without violating any antitrust laws. Because only the largest firms have access to enough data to compete, innovation is losing its power to make markets fairer.

The legislators who wrote the existing laws assumed that competition would make it hard to concentrate market power for long. In the old days, it was assumed innovation would eventually taken care of ordinary market concentration. That has changed. Innovation is shifting to data-driven machine learning. Insights are no longer the product solely of human ingenuity. They are now the result of the automated analysis of huge amounts of data. More and more, the success of a firm rests on its ability to use the information it possesses. Because only the largest firms have access to enough data to compete, innovation is losing its power to make markets fairer.

And to discuss Facebook “The Autocracy App” is also beyond the scope of this post. Mark Zuckerberg now spends much of his time apologizing for data breaches, privacy violations, and the manipulation of Facebook users by Russian spies. This is not how it was supposed to be. But the narrative has been seized. All we can talk about are these gangs of “patriotic trolls” who use Facebook to spread disinformation and terrorize opponents across the world. And in the United States, the platform’s advertising tools remain conduits for the most vile subterranean propaganda.

CONCLUSION

What sets the new digital superstars apart from other firms is not their market dominance; many traditional companies have reached similarly commanding market shares in the past. What’s new about these companies is that they themselves are markets. Amazon operates a platform on which over $200 billion worth of goods are bought and sold each year. Apple runs gigantic marketplaces for music, video, and software. As the world’s largest music-streaming service, Spotify provides the biggest marketplace for songs. The Chinese e-commerce behemoth Alibaba manages the world’s largest business-to-business marketplace. Meanwhile, Google and Facebook are not just the dominant search engine and the dominant social media platform, respectively; they also represent two of the world’s largest marketplaces for advertising space.

Markets have been around for millennia; they are not an invention of the data age. But digital superstar firms don’t operate traditional markets; theirs are rich with data.

But I think this focus on data privacy has obscured the real dangers of these information monopolies as I have noted above – and the tech monopolies like it that way. Data issues are far easier to discuss and address. Cesar Ghali of the Computer Science Department at the University of California Irvine has done a study of the networking architecture of social media (and media in general) and the dissemination/flow of information, looking at the collection of personal data and targeted advertising, and news sites, among others. And he thinks data protection is somewhat futile. In a nutshell … and you have undoubtedly heard this before:

In today’s digital world, we’re continuing to upload more of our personal information to all of these interwebs in exchange for convenience. As such, some degree of information governance should be necessary to protect us. Companies should be held accountable for misusing people’s data. But they will not to any serious degree. Why? Because the likes of Google, Facebook and Amazon generally making your life easier and/or better, and it means the very algorithms that enable this need to be fueled by massive amounts of data. The more data they have, the more capable and sophisticated they become. And we’ll keep feeding them. Because they make life easy. It’s that simple.

You have seen the reports. On Amazon, buyers can tick options to quickly identify the kinds of products they are looking for. Study after study has shown that Amazon rarely offers the cheapest choice, but buyers value the ability to find something easily that closely matches their needs. It’s easy.

If these monopolies can’t collect data and serve up ads, they are cooked. Which is why despite all the sound and fury yesterday these tech companies will make sure that any changes in the privacy laws do not destroy the data-driven model that makes this all so profitable for them.