25 September 2018 (Athens, Greece) — Every weekend my media unit publishes the “BONG REPORT”, a selection of what we think are the best Tweets collected by Jonathan Maas from his daily distributions (which he calls BONG!) of articles, posts and sources of information he finds on Twitter. They are mostly in the areas of forensic technology and discovery. This past weekend’s edition had as the lead story “AI-driven discovery process produces millions of unresponsive documents” and it produced a tsunami of email responses.

The article in question is a piece written by Casey Sullivan, a lawyer and Content Marketing Specialist at Logikcull. Casey wrote about In Re: Domestic Airline Travel Antitrust Litigation, in which plaintiffs allege that United, Delta, Southwest, and American Airlines violated the Sherman Act by colluding to reduce seat capacity in order to fix ticket prices. As pre-class-certification discovery began, both the plaintiffs and United deployed technology-assisted review (TAR) in order to help them work through the extremely large body of potentially relevant documents.

Just a short note to my readers not in the e-discovery ecosystem. Not all that long ago a new philosophy emerged in the e-discovery industry which was to view e-discovery as a science — something that is repeatable, predictable, and efficient, with higher quality results and not an art or something that is recreated with every project. Underpinning this transformation was the emergence of new intelligent technology known as TAR, predictive coding, machine learning, or simply AI. It was a “smarter review tool” meant to mimic and automate the document coding of a human reviewer. This approach was to deliver real results when it comes to controlling the costs of litigation. And given it was “artificial intelligence driven” vendors said it would be perfection. But in many cases (not all) it has promised more than it can deliver. Over the last few years we have reported from the trenches of e-discovery review centers across the country … the stories of failure after failure of predictive coding software.

Casey’s piece is excellent: well researched, well written, cuts to the chase. He has become a “must read” in the e-discovery firmament. He details how United’s TAR process ended up producing more than 3.5 million documents … with only an estimated 600,000 docs, or 17 percent, being responsive to the plaintiff’s request. Said Casey:

That AI-powered document dump left the plaintiffs with little option but to demand an extension of six months, just to get through the millions of documents accidentally rerouted their way.

Suggestion: for some good detail on the back-and-forth on the TAR issues, read Maura Grossman’s two declarations filed in the case. She acted as special e-discovery consultant in the case. You can access the court filings here.

Casey ended the piece with a killer line:

The legal industry has been slow to adopt TAR, and not just because gargantuan MDLs make up only a tiny share of the national docket. The cost, complexity, and potential risk of such processes seem to have prevented their wider adoption. Cases like In Re: Domestic Airline Travel Antitrust Litigation are unlikely to help TAR take flight.

We received a stream of emails in response to that weekend BONG! post, most from vendors and law firms, who told us the TAR process in the airline case was ill-conceived and poorly executed. The tenor of the responses (and this is a composite of the 72 emails we received):

This TAR “review” was a joke. Somebody did not understand the science and statistics involved. The probability theory involved. There are proper protocols, and minimum recall rates, and reasonable levels of precision. And validation samples. It is human screw up, not the tech. This is tricky stuff!!

Yes, it is. And perhaps due to the “black box” nature of TAR technology, it’s why it took United weeks to explain the process and the discrepancies. To nobody’s satisfaction. Plaintiffs response to United’s answer? “We do not understand your explanation”.

By and large, lawyers tend to be pretty well prepared and understand what they need to address the issues at the beginning of each case. But when it comes to e-discovery competence most are found wanting. Lawyers from bigger firms generally tend to have more familiarity with technology tools, which can be expensive. And lawyers at bigger firms tend to have bigger budgets with which to work — and therefore they tend to have used or have a colleague that has used e-discovery tools. But note: the lawyers in In Re: Domestic Airline Travel Antitrust Litigation came from Am Law 50 firms with heavy e-discovery experience.

And let’s be honest. The legal media has pulverized us with TAR (more than 2,040 references in articles since August 1st of this year alone). Granted, most are puff pieces generated by vendors or they are just light scans by media outlets. Who has time to read long articles? So we feel great because we’ve “read so much!” that we feel we’ve sufficiently “got the gist” to forego actually having to study TAR. And in practice, despite all the buzz – and several generations of technology development – predictive coding is still used in less than 1 percent of cases. That’s a trivial adoption rate for most technology, but especially for one that gets so much attention.

The trouble starts when TAR goes into the crapper because somebody (finally) realizes it is acting outside the framework of expectation and needs to be corrected. Often too late, as in this case. Which is why the “Lord High Commissioner” of TAR/predictive coding, Ralph Losey, suggests (demands?) a multimodal approach to information retrieval in general, one that utilizes all types of search methods, including predictive coding. Plus a Subject Matter Expert throughout.

But there is more to it. Let’s discuss the elephant in the room.

Perception

This might be a bit of stretch but hear me out. Apple’s new watch sounds like a win for anyone interested in their heart health. It will notify wearers of a slow or irregular heart rhythm, and it can take a basic electrocardiogram (ECG), a recording of the electrical activity of the heart. During Apple’s presentation of the new watch on 12 September the company boasted of its FDA clearance and basked in praise from American Heart Association president Dr. Ivor Benjamin. Everybody was gaga.

But last week here in Athens I was at a medical technology convention (I am working with the health clinic and hospital on my island to find some new tech for better ambulance/doctor response times) and I spoke to a heart doctor who basically said “if you think an Apple Watch is nifty, buy one. But do not buy it for your health. It will not improve your health, and it could even bring you harm”.

He conceded that early detection seems like a good idea, especially for atrial fibrillation (AF). AF can increase a person’s risk of stroke, and many people who have AF don’t know it. We also have effective ways to treat it, including drugs that block clotting—called anticoagulants—that can reduce the risk of stroke in patients with AF and other risk factors, such as high blood pressure or diabetes.

But the first obstacle when it comes to AF screening is understanding that the vast majority of people do not have AF, but most people do have normal variation of their heart rhythm, which can mimic AF. Benign premature beats, for instance, can make your rhythm irregular. This makes ECG accuracy a problem. Said the doctor:

You need to understand that AF screening with medical-grade 12-lead ECGs is the way to go. More accurate than the one-lead ECG used in the Apple Watch. The specificity of an ECG (its ability to correctly identify people who don’t have AF) is around 90 percent. That may sound good, but the 10 percent of the time that an irregular rhythm is falsely labeled as AF will exert a massive effect in large populations—like the millions of people who may soon own the new Apple Watch. If the watch is wrong 10 percent of the time, that means nearly 100,000 people will be falsely diagnosed. Do you realize the stream of false positives that will result?

Sending hundreds of thousands of wrongly diagnosed people to the doctor scares me. In addition to needless anxiety and costs, this is hazardous because while some doctors will simply reassure the patient, many other doctors will order tests. Since all medical interventions come with risks, many people will suffer harm from unnecessary tests and procedures.

But it today’s world people just want instant gratification so they’ll buy the watch.

BANG! Instant gratification! I thought about the conversation I had in June before my summer break with the EMEA Legal Director of a dominant company in the TMT sector (technology, media, and telecom) who I see several times a year at various TMT events:

Look, I get predictive coding. I do not necessarily understand it. But I see where eventually it will advance, it will somehow get better. Why? Because of the collision of two simple, major trends you and I have discussed ad nauseam. First, the economics of traditional, linear review has become unsustainable. Two, the early returns from those employing predictive coding are somewhat impressive. But flawed. In my world today, vis-a-vis the AI our company employs, this TAR stuff is primitive. Primitive. My staff tells me about all the screw ups. This stuff is not ready for prime time.

Listen: we use AI to manage several global wide telecommunication networks, my colleagues are going gangbusters with AI in cancer analysis and treatment, AI landed rovers on Mars, etc., etc. And you can’t find my relevant documents without doing a statistical, mind-numbing dance? I want this stuff to work like my online services, my e-commerce sites, my Web search engines. I am spoiled. I have developed expectations. I get near-immediate access to vast data sets. It’s called “user expectation”. Searchable and accessible online. On an unmediated basis — that is, I do not need a techie, I do not need an archivist.

And we’re using complex natural language software that can parse and (in a way) “understand” data. All of us can use it. We’ve been using these information-extraction techniques for years, and none of them were developed by those e-discovery companies of yours.

When your TAR stuff becomes push-button so that even I can do it, then call me.

His points have been repeated by many others. I get it. Speed. Immediacy. Our technology has got us to the point where users have come to expect near-instantaneous response times even when searching databases containing many billions of items. Users are increasingly intolerant of slow response but more importantly the wrong response. And if you look at other functions like performance measurement and production engineering they get it.

I tried to argue that in e-discovery, we are dealing with much richer data types and more sophisticated records then we have dealt with before, requiring special search. And data types (file formats) each have data-encoding rules, compounded by the complexity of the myriad options and subtypes associated with some data types. But it fell on deaf ears. Users (quite rightly) expect e-discovery services to allow them to search across multiple sources of content. Accurately. And quickly. Because if we can land a rover on Mars …

I discussed my TMT colleague’s “perception” with Jonathan Maas. He had, perhaps, the perfect rejoinder:

Ok. I do understand the point your TMT colleague is making. But in the law we are not looking for tins of paint to buy, or hotel rooms to book. We’re reading incredibly nuanced documents written in highly technical language particular to a specific business, or incredibly complex information referred to in very relaxed, colloquial wording. The technology works. It just needs proper human input, monitoring.

You can read more about Jonathan’s thoughts on the United case and TAR in today’s issue of Artificial Lawyer by clicking here. His point: “this was human error, plain and simple. Probably confounded by good old ignorance. The technology works fine if set up and monitored correctly. More often than not: it’s only a puppy. There will be errors”.

The puppy analogy is perfect, if only because it ties in with a conversation I had with a TAR expert yesterday about the United case. His points:

Well, Jonathan gets it. We are really at very, very early stages at TAR (assuming that was why he used the puppy comparison) despite what any vendor tells you at LegalTech. We need a lot of time (and money) to get the kinks out. Given the slow (very quiet) march of Google and Microsoft in this same area, I suspect they will eventually come out with a better TAR. And they don’t have the competitive pressures we do in the e-discovery industry. It is not their primary business. They have time (and money) on their side. I watch these “new developments in TAR” press releases hawked by e-discovery vendors and I suspect it is merely to wind up their competitors, to grab media attention. Despite all these lofty revenue numbers thrown around by Rob Robinson and others, we are a small industry and back-biting seems to be our modus operandi.

And, look. It is simple. TAR (all AI) is inherently unstable. TAR systems, through their very operations, are in constant flux as they acquire and instantly analyze new data, then seek to improve themselves on the basis of that analysis. Which is why you need to be monitoring. On that point Maas is straight on.

One more conversation. I had a chat this morning with a long-time colleague who runs the e-discovery unit of a pharmaceutical company. We often meet-up at the Mobile World Congress or a RSA cyber conference, but every year at the Frankfurt Book Fair (we are both bookaholics). His thoughts:

Hmm. The United case. No specific thoughts but I do see Jonathan’s point regarding nuanced, pretty technical documents. I think this applies to most tech companies but we are especially cognizant of the governance, risk management, sensitive data issues that discovery requests pose for us. Especially privacy/security/IP concerns. I have never been directly involved in a MDL case like the United case but I have learned (from LegalTech and conducting our own beauty contests with vendors) how to manage/search complex enterprise systems. And it certainly is not push button. Well, not yet but one has hopes.

We have stayed away from TAR for the time being. I see cost and complexity issues but I will not go into that right now.

Frankly I am more impressed by the vendors in the text analysis, network analysis, and text mining area I meet at the enterprise search and discovery conferences we attend. Especially what Microsoft has in the pipeline. It is one reason we are building out our own e-discovery engine which is built on the Python programming language. Early days yet.

I have not given up on e-discovery vendors but I am disappointed by their technology events, quite frankly. I was in D.C. last month at a meeting with one of our law firms so I popped by ILTA which was in town. My first observation? All of these video game characters walking the halls. Has the e-discovery industry demeaned itself to the point it needs a “theme park”? Is the product not good enough to hawk? Is the competition so fierce, the product so commoditized you need to stoop that low for attention? I mean, in all the years I have gone to MWC or RSA (or Frankfurt with you) I have not seen cartoon characters since … well, never.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Earlier this summer McKinsey & Company put out a survey on tech and disruption and noted that experience has shown that it typically takes a decade or more to figure out what can truly be done with new tech capabilities. They cited the iPhone (although I think the Apple Watch is the real tech marvel). And they noted that all of the Internet technology necessary to support the World Wide Web existed by 1982. That included a working Internet, a good-sized community of users with a need to communicate organized information of various types, the concept of hypertext, the Domain Name System, and desktop PCs connected to the network. But the World Wide Web itself wasn’t invented until 1991 – it took a full 9 years to work out the implications and realize that this application was possible.

And Ron Adner and Rahul Kapoor posted an article in the Harvard Business Review (a continuation of their “let’s take a wide lens” series on tech and innovation). Some technologies and enterprises seem to take off overnight (ride sharing and Uber; social networking and Facebook/Twitter), while others take decades to unfold (high-definition TV, cloud computing). But they say most technology depends on the ecosystem. Both established and disruptive initiatives depend on an array of complementary elements — technologies, services, standards, regulations – to show they are really value propositions. Because, as they note and the people I interviewed above have noted, customers/consumers will do a drill down and determine how much additional development will be required before the technology is ready for commercial prime time.

Ok, cloud and storage are easy. As I said, for new technology, the key factor is how quickly its ecosystem becomes sufficiently developed for users to realize the technology’s potential. In the case of cloud-based applications and storage, for example, success depended not just on figuring out how to manage data in server farms, but also on ensuring the satisfactory performance of critical complements such as broadband and online security.

Perhaps such comparisons with TAR is unfair. But as with any cycle of adoption for new technology, current perceptions of the nature, costs and benefits of this new TAR technology remain mixed. Yes, the legal industry is becoming more sophisticated about applied data analytics, data mining, business intelligence .. and even TAR. But before adoption can broaden a lot of common misperceptions must be addressed. The mantra of experts like Ralph Losey and Jonathan Maas must be pounded home:

- vendors, purge your hype and bad science;

- explain relevance is never static, it changes over the course of the review, hence human monitoring is crucial;

- and for God’s sake have a senior TAR Subject Matter expert give his personal attention for the days of training and the days of document review work

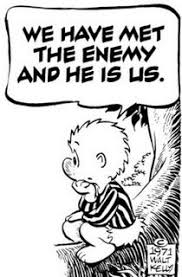

Don’t kill the puppy.