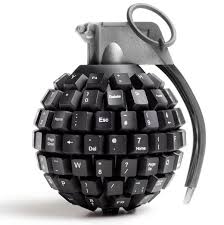

Airline systems, like all networks, are vulnerable to hacking. And you know what? Governments WANT your smart devices to have stupid security flaws.

6 September 2018 (Chania, Crete, Greece) – During the year I set a somewhat (overly) ambitious self-challenge: read four books a month. I do not suffer from selection. I belong to a publisher’s consortium (a membership that came from a long-term part-time position as a professional reader of submitted manuscripts for a publisher who became one of my IP clients) so I receive about 10 books a month.

Some books stay in my libraries (I keep duplicate copies of my favorite and most-referenced books at my home in Greece and my home in Brussels) but the bulk go to my foundation for distribution to libraries and schools across Europe that have few financial resources and are in desperate need of books.

This summer I shipped 20 books home to Greece in a wildly (over-optimistic) dream I’d get through 10. I got through four. Well, 5. Last week my publisher sent me a paperback copy (the kind they send designated book reviewers before a book is released) of the on-fire Bob Woodward book “Fear” which I knocked off in one day.

I only have one rule for a great non-fiction book: it needs to make me think. And Bruce Schneier’s new book “Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyper-connected World” hit the mark. Some thoughts:

Hardly a day now passes without reports of a massive breach of computer security and the theft or compromise of confidential data. I am suffering from “breach fatigue”. But hang on: Schneier says that digital nightmare is about to get much worse.

The burgeoning threat, writes Schneier, … and he is obviously not the only chap noting this … arises from the rapid expansion of online connectivity to billions of unsecured nodes. That bloody “Internet of Things”, in which physical objects and devices are networked together, is well on its way to becoming an “Internet of Everything”.

You know this part. But for the unwashed, over the past decade or so, a growing number of products have been sold with embedded software and communications capacity: household appliances, cars, medical instruments and even clothing can now be monitored and controlled from afar. More of the same is on the way, as smart homes yield to smart cities and automated systems assume a larger role in the management of critical infrastructure. The Stuxnet computer worm used to attack Iran’s uranium-enrichment programme remotely in 2010 was an early, audacious indicator of the threat.

To those pundits with rose-colored glasses, enhanced global connectivity has many advantages for knowledge sharing, commerce and convenience. Securing it, however, is a daunting prospect. Go to any cyber conference and the mantra is repeated: the all-too-familiar vulnerability of computer networks – their susceptibility to failure, disruption and interference by malware, viruses and other factors – is amplified as practically everything becomes computerized. That relentless expansion of cyberspace into the physical domain brings with it new threats to power systems, mass transportation, public health and safety, and even political institutions, as effectively demonstrated by the Russian information operations that targeted the 2016 US presidential election.

As my regular readers know, my mantra has been the same: no country has even come close to the U.S. in harnessing the power of computer networks to create and share knowledge, produce economic goods, intermesh private and government computing infrastructure including telecommunications and wireless networks, using all manner of technologies to carry data and multimedia communications, and control all manner of systems for our power energy distribution, transportation, manufacturing, etc. … and so left the U.S. as the most vulnerable technology ecosystem to those who can steal, corrupt, harm, and destroy public and private assets, at a pace often found unfathomable.

Despite its lurid title, Schneier’s book is sober, lucid and often wise in diagnosing how the security challenges posed by the expanding Internet came about, and in proposing what should (but probably won’t) be done about them.

As he notes, security was not a primary concern in the early design of the Internet in the mid to late twentieth century. Developers of early efforts, from the US Department of Defense’s ARPANET onwards, did not anticipate the Internet’s explosive growth or coming role in global commerce and communication. Even today, there is little incentive to prioritize security above other concerns – so, for example, e-mails may or may not be from the sender named.

Surveillance capitalism

Surprisingly to some, much of the business of the Internet is predicated on insecurity. “Surveillance capitalism” – the collection of user data and its sale to advertisers and others – depends on vulnerable Internet practices, as does intelligence collection for national security and law enforcement. Governments act as if their need to monitor the Internet can be satisfied without any larger compromise of security. That, writes Schneier, is not so.

In principle, he explains, securing the Internet is straightforward, but it would demand concerted government action at each step. Financial incentives should be realigned to promote security and penalize failure by mandating that manufacturers disclose defects in commercial software, making them legally liable for defects. Security should be required in new devices, and rewarded through subsidies and tax breaks. Data should be encrypted to secure them against unwanted collection. Critical infrastructure – power grids, communications and transportation – should be protected by bolstering network security or disconnecting them from the network altogether.

Government agencies are fully aware that the expanding Internet “will create an incalculably larger exploitation space for cyber threat actors”, as the US National Counterintelligence and Security Center noted in a 2018 report, Foreign Economic Espionage in Cyberspace. Yet Schneier’s views on security differ sharply from those of many government officials in the United States and elsewhere. For instance, Schneier considers strong encryption to be indispensable for personal and network security. The US Department of Justice sees it as “a serious challenge to effective law enforcement“.

Similarly, Schneier advocates ruling out “back doors” – design features that enable users, authorized or not, to bypass security and to decipher encrypted communications. He reasons that they render entire systems more vulnerable. But as then-UK home secretary Amber Rudd said last year, lack of access to encrypted data “in specific and targeted instances is right now severely limiting our agencies’ ability to stop terrorist attacks and bring criminals to justice”. Schneier also feels that it would be unfeasible and inappropriate to ban anonymity online. But the US Department of Justice insists that impenetrable anonymity “poses a unique and significant threat to public safety” in criminal contexts.

“Warning, Will Robinson! Priority clash!”

Because Schneier and his opponents in law-enforcement agencies are responding to different problems on different timescales – solving a crime today versus fixing the whole Internet for the foreseeable future – it is difficult to say categorically that one side is right and the other wrong. But Schneier argues his position well. And to compensate for the admitted loss of collection capability that would follow from improved Internet security, he proposes to “make law enforcement smarter” through security research, enhanced computer forensics and new career paths.

Although cybersecurity is a hot-button issue in policy circles, progress is hindered by bureaucratic lethargy, especially on fundamental questions. In July, the US Government Accountability Office reported that 1,000 of its recommendations for addressing cyber threats have yet to be implemented, placing government information systems increasingly at risk. Governance seems to be an even harder problem than cybersecurity, leaving Schneier to predict that the United States “will do nothing soon”.

Correct, he is not optimistic but he does try to make a few valiant points and he is spot on:

- To help devise a sensible response, scientists and engineers need to get more involved in the policy process.

- If the question is what sort of Internet is compatible with a humane and enlightened society, technologists are not the only ones who will need a seat at the table.

I will leave you with my favorite quote from the book. Citing vehicles, airlines and power plants he says: