(with thanks to staffers Catarina Conti and Silvia Di Prospero)

In Part 1 my focus was on the big take-aways from the Festival

as they impact the advertising/media industry.

Here in Part 2, my focus is on the extensive discussions we had on the

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

2 August (Serifos, Greece) – As I noted in Part 1, every June our team makes its pilgrimage to the annual Cannes advertising conference. Or to give it its full honorific, the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity 2018 – what I like to call “The Conference of the World’s Attention Merchants”. Because over the last decade, the festival has evolved to include not only more brand clients but also, due to media fragmentation which has led to the change of some and the birth of others, an expansion into tech companies, social media platforms, consultancies, entertainment and media companies — essentially the entire attention ecosystem. And, alas, as I noted, Don Draper is (almost) dead.

This year the arrival of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) led a bevy of e-discovery law firms and e-discovery vendors to send representatives. One of the e-discovery lawyers nailed it. He said:

Look, it’s going to be an iterative process, and this GDPR compliance stuff will be a marathon and a theme far into the future. There will be many, many, many lessons learned. But I suspect the regulators will go for the the low-hanging fruit like audits of data processing activities. That’s the real easy stuff.

And … voila! A few weeks ago both the Dutch and the French data protection authorities announced (in almost identical language) they would conduct “[GDPR] audits of registers of data processing activities at selected companies”.

There were the expected withdrawals: some U.S. vendors like Verve (a big player in the mobile advertising space) and Drawbridge (a buying platform/identity vendor) have pulled out of Europe entirely to avoid the cost of getting their businesses GDPR-compliant, and to avoid any risks should they fail to do so.

NOTE: Drawbridge is a good example to use for what is at stake here for many media vendors, and I had a lengthy chat with them. Drawbridge’s two arms consist of a media-buying group and a data business licensing its identity solution to other companies.

The problem Drawbridge faces is that under GDPR, it must obtain individual consumer consent to access data, and then again to conduct services like targeted advertising. Drawbridge has no consumer-facing brand or touch points, so it must coax consent from people who don’t know the company and on the back of app operators or media companies with first-party relationships. And it must do the same to apply its cross-device profiles for advertising.

GDPR compliance would be a monumental task, and the quality of its service would be undercut even if Drawbridge committed to securing consent for targeted advertising in the EU.

Most ad tech executives at the Festival were pretty candid in their predictions that other noncompliant U.S. vendors will also be forced to leave Europe in the coming months (22 more as of the date of this post), with many vendors unveiling their plans for a “two web sites” approach: one for U.S. consumers, and the other for rest of the world.

And there was much grumbling by publishers that have felt at a disadvantage as a direct result of Google’s last-minute GDPR policy changes (see my pre-Cannes Lions post here) so they had multiple conversations with the tech giant at Cannes … behind closed doors. Meanwhile, advertisers were asking some difficult GDPR-related questions of vendors about how they can ensure they’re passing “consent” on verified audiences and inventory, and handling third-party data.

Yes, all kinds of chats and presentations about GDPR “consent” and the proper handling of “third-party data”. But the most relevant (and certainly the most important issue) were the discussions about the transparent algorithmic decision-making provisions of the regulation, and machine learning. The GDPR requires data controllers using algorithms for automated decision-making to explain the logic of that decision-making. Because tucked away in recital 71 of the GDPR there is even a requirement to use “appropriate mathematical or statistical procedures” to avoid or reduce risk resulting from errors or inaccuracies.

I will address the “algorithm issue” in a moment but first lets run through some of the easier issues:

CONSENT

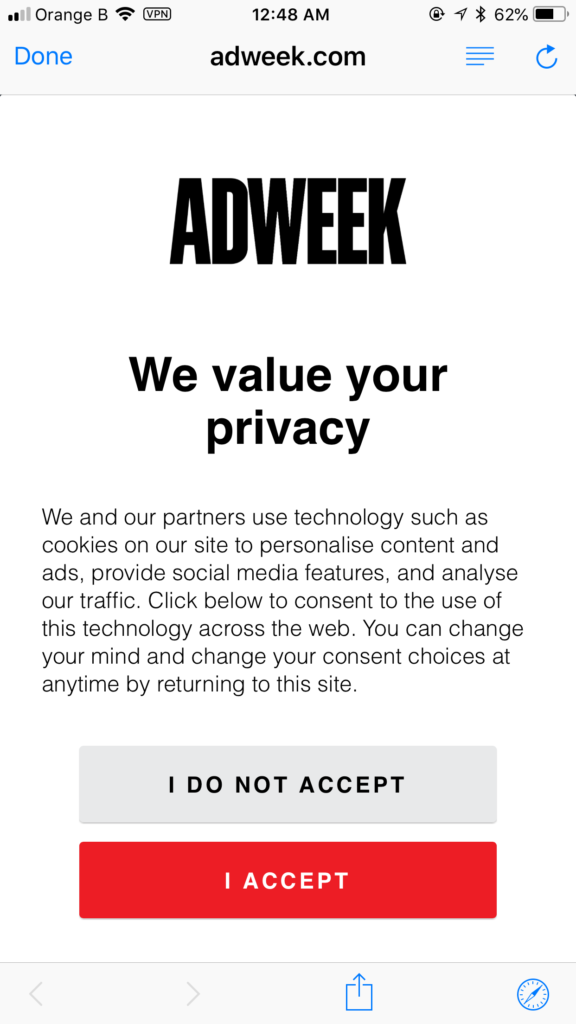

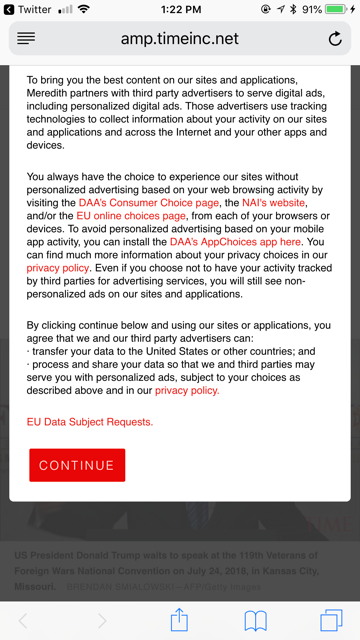

“The GDPR sets a high standard for consent. But you often won’t need consent. If consent is difficult, look for a different lawful basis”. That was the nugget offered by an e-discovery/privacy attorney attending the Festival whose primary clients are in the media industry. Other points:

- Consent means offering individuals real choice and control. Genuine consent should put individuals in charge, build trust and engagement, and enhance your reputation.

- Check your consent practices and your existing consents. Refresh your consents if they don’t meet the GDPR standard.

- Consent requires a positive opt-in. Don’t use pre-ticked boxes or any other method of default consent.

- Explicit consent requires a very clear and specific statement of consent.

- Keep your consent requests separate from other terms and conditions.

- Be specific and ‘granular’ so that you get separate consent for separate things. Vague or blanket consent is not enough.

- Be clear and concise.

- Name any third party controllers who will rely on the consent.

- Make it easy for people to withdraw consent and tell them how.

- Keep evidence of consent – who, when, how, and what you told people.

- Keep consent under review, and refresh it if anything changes.

- Avoid making consent to processing a precondition of a service.

- Public authorities and employers will need to take extra care to show that consent is freely given, and should avoid over-reliance on consent.

For some “bullet proof” consent forms, the following mobile versions were on offer (from two vendors that deal in enterprise marketing analytics and compliance services):

CONCIERGE MARKETING/THIRD-PARTY DATA

At a panel discussion about concierge marketing – which is the idea of servicing and personalizing marketing – a representative from Nestlé spoke about how user reviews are proving to be a good source of first-party data to get around GDPR concerns. Under GDPR, companies that collect third-party data are required to revamp their processes for collecting personal information, and consumers are allowed to opt-out. As brands have ramped up their preparation and execution for GDPR, marketers are increasingly focusing on first-party data practices that ask consumers to explicitly fork over their own information – think email signups, mobile app downloads and comments.

Marketers have noted they are looking to move away from their reliance on third party data. And these points are important for my e-discovery readers who are helping their clients with GDPR issues.

NOTE: What is third-party data? Every business uses some form of customer data, mostly first-party, which means that the company has collected and stored the data itself. This data is used to manage current customers. But when companies want to find new customers, they use third-party cookies to target and retarget prospective customers across multiple touch points – a practice that some marketers here say is already dying.

In advertising/marketing that’s a biggie. As I noted in a longer post during our Cannes Lions coverage last year, the idea of third-party data basically pulls from two areas:

- First, there is the original reason third-party data became important to marketers, which is that they wanted to buy categories of potential buyers based on socioeconomic status, age, income, etc.; in other words, third-party data became important for data append use cases.

- The second reason third-party data became important was because ad systems became dependent on it. Their business model relies on cookie sharing across the board.

I have seen a shift in brands. I am starting to see brands turn away from third-party data as consumer concerns for data privacy rise. I expect to see that shift continue as companies are forced to rethink their engagement channels and begin to look toward direct engagement tools to reach their customers.

And the reason it is a “biggie”, as I noted above, is because the third-party data ecosystem is in danger. I think we can expect to see smaller ad-tech companies that depend on third-party data go out of business as they struggle to keep up with policy changes or be forced to make major changes to their core business model. The demise of these smaller companies and third-party ad networks will further elevate the Facebook/Google duopoly within the ad ecosystem. It just has to happen and not quite what the EU Commission had in mind: it will make Facebook and Google stronger. GDPR has become the bogeyman in the real data world, not quite understood in the cloistered hallways of Brussels.

But in the industry, it was totally expected. Google and Facebook can easily box out rivals further. The two control more than three-quarters of digital advertising and have the cash to pay lawyers for compliance steps and handle any fines (Google apparently has 2,500 people working on GDPR preparation and execution based on an internal video from Google advertising chief Sridhar Ramaswamy and Google general counsel Kent Walker congratulating the team).

Smaller ad firms, which provide alternative services for marketers to target ads, have less financial muscle. So many have simply gone to the “dark side” for protection.

ARE FACEBOOK AND GOOGLE MERELY ARBITRAGING THE DATA LAWS?

Which brings me to one of the major “let’s talk about this in the bar” topics: the power of Facebook and Google. Ok, some obvious points. The data laws (including GDPR) are simply not fit for purpose. The advertising/media industry has transformed itself while still regulated by antiquated frameworks. GDPR has come a long way but innovation is running circles around legislation. And let’s not glory in California’s recently passed “GDPR legislation”. That citizen initiative was 90% incoherent and 10% class action, ambulance chaser heaven. One would think the legislature promoted the initiative so as to collect bribes … er, campaign contributions … from both defendants and trial lawyers.

Yes, sooner or later some companies will offer iron clad data privacy as part of their “value proposition”. It would be good business sense. You know, a “Terms and Conditions” that would start off with something like this:

FIRST, we have no right to collect and/or aggregate your personal information from multiple sources without your direct op-in permission calling out the specific information we will collect or monitor, the sources we will use, and the time period this information will be kept before being destroyed.

But back in the real world …

Traditionally technology companies have argued that they host information neutrally, but that defense is slipping (see my points above). As laws such as the GDPR try to take a bite, acting as a publisher with broader freedom than others to handle and to disclose personal information starts to be attractive. Why not, lawyers whisper, combine the advantages of both?

As scandals over the misuse of personal information proliferate and data protection laws are tightened, technology companies are leaping to a surprising conclusion: they are publishers. Not always, of course, but when it suits them.

Facebook emphasised its role as a publisher with editorial discretion in a California court last month in an effort to block a lawsuit from a developer. Google attempted something even more audacious in a UK case earlier this year involving the “right to be forgotten” in search engine results. It laid claim to an exemption for publishers of journalism, art and literature under European law.

Now THAT was cheeky. Such claims sit awkwardly with the customary insistence of Facebook, Google and other tech platforms that, in Facebook’s careful formulation, they are not “the arbiter of the truth”. Correct me if I am wrong but wasn’t it Mark Zuckerberg back in April who told the U.S. Senate “I agree that we are responsible for the content, but we don’t produce the content.”

This sort of thing is inevitable when laws overlap and the same item of information can be defined differently. Is a photo snapped in a public place publishable as journalism or protected as a sensitive piece of personal data that identifies the subject’s ethnic origin and physical or mental condition? At a technical level, when everything is broken into bytes, there is no simple distinction.

European law balances the right to freedom of expression with the right to privacy (which is hard to distinguish from data protection). But the law is not supposed to be a pick and mix. Those who want to facilitate the former and override the latter, whether as individuals or companies, must do so carefully and in the public interest.

Interpretations of what GDPR says about publishers is still up for debate (due in no small part to the “connective tissue” deleted between numerous sections during the negotiations), and may only be settled in court years from now. Many at Cannes were unconvinced that Google and Facebook are meeting even the spirit of the law:

Look, everybody expected a change in culture. Ain’t gonna happen. Brilliant lawyers will always be able to fashion ingenious arguments to justify almost any practice. But with personal data processing we needed to move to a different model. We did not get it.

Under the GDPR, organizations can be controllers or processors. While a processor processes data on behalf of a data controller, a controller determines the purposes for, and the manner in which, personal data is processed. So Google, of course, lays claim to being a controller which allows it to make decisions regarding how the data that is received from publishers and collected on publishers’ pages is used.

But the publishers have tried to argue that it would be more logical for Google to be a processor – asking whether the firm has sought guidance from regulators on their decision – but even they acknowledged that in some cases Google will be considered a controller. Underlying all of this is what the publishers say is a lack of information about what Google plans to do with this data. Google, they said, is claiming “broad rights over all data in the ecosystem” without full disclosure and without giving publishers the option for Google to act as a processor for some types of data. This, they added, “appears to be an intentional abuse of its market power”.

Meanwhile, Google has proposed it will rely on affirmative, express consent as the legal basis for this processing – and that it wants publishers to obtain this from their users on its behalf. Although publishers are currently required to get consent from their end users, the GDPR sets a higher bar for consent (as noted above), requiring that it is freely given, specific and granular.

THE GDPR AND ALGORITHMIC ACCOUNTABILITY

This section dovetails a bit with my recent piece on AI and bias (click here). It dovetails with the GDPR because part of what the regulation does is provide a “due process infrastructure” to try and ensure that algorithms are made accountable, to work toward the responsible adoption of algorithmic decision-making tools. The (misplaced) hope always seems to be that laws could enforce such goals.

Such was the hope of the GDPR, which has some provisions — such as a right to meaningful information about the logic involved in cases of automated decision-making — that seem to promote algorithmic accountability. But to Brent Mettstadt, a self-proclaimed “data lawyer” who attended the festival, the GDPR might actually hamper it by creating a “legal minefield” for those who want to assess fairness. The best way to test whether an algorithm is biased along certain lines — for example, whether it favors one ethnicity over another — requires knowing the relevant attributes about the people who go into the system. But says Brent:

The GDPR’s restrictions on the use of such sensitive data are so severe and the penalties so high that companies in a position to evaluate algorithms might have little incentive to handle the information. It seems like that will be a limitation on our ability to assess fairness.

The scope of GDPR provisions that might give the public insight into algorithms and the ability to appeal is also in question. As written, some GDPR rules apply only to systems that are fully automated, which could exclude situations in which an algorithm affects a decision but a human is supposed to make the final call. The details (as always) will need to be clarified in the courts.

Does the GDPR prohibit machine learning? A big question at the Festival given how important machine learning (ML) is to the advertising/media industry. A complex topic requiring a nuanced discussion (and fodder for another post) so, for now, a few bullet points:

- The short answer to this question is that, in practice, ML will not be prohibited in the EU after the GDPR goes into effect. It will, however, involve a significant compliance burden, which I’ll address shortly.

- But … maddeningly … the answer to this question actually appears to be yes, at least at first blush. The GDPR, as a matter of law, does contain a blanket prohibition on the use of automated decision-making, so long as that decision-making occurs without human intervention and produces significant effects on data subjects. Importantly, the GDPR itself applies to all uses of EU data that could potentially identify a data subject—which, in any data science program using large volumes of data, means that the GDPR will apply to almost all activities (as study after study has illustrated the ability to identify individuals given enough data).

- When the GDPR uses the term “automated decision-making,” the regulation is referring to any model that makes a decision without a human being involved in the decision directly. So this could include anything from the automated “profiling” of a data subject, like bucketing them into specific groups such as “potential customer” or “40-50 year old males,” to determining whether a loan applicant is directly eligible for a loan.

- So as a result, one of the first major distinctions the GDPR makes about ML models is whether they are being deployed autonomously, without a human directly in the decision-making loop. If the answer is yes – as, in practice, will be the case in a huge number of ML models – then that use is likely prohibited by default. [NOTE: the Working Party 29, an official EU group involved in drafting and interpreting the GDPR, has said as much, despite the objections of many lawyers and data scientists]

- So why is interpreting the GDPR as placing a ban on ML so misleading? Says Cloe Barneswell of Deloitte who has taken these provisions apart:

- Because there are significant exceptions to the prohibition on the autonomous use of ML—meaning that “prohibition” is way too strong of a word. With the GDPR in effect, data scientists can now expect most applications of ML to be achievable—just with a compliance burden they won’t be able to ignore.

- She also noted the regulation identifies three areas where the use of autonomous decisions is legal:

- where the processing is necessary for contractual reasons,

- where it’s separately authorized by another law, or

- when the data subject has explicitly consented.

- In practice, she says it’s that last basis – when a data subject has explicitly allowed their data to be used by a model – that’s likely to be a common way around this prohibition.

- I have two points:

- Managing user consent is not easy. Users can consent to many different types of data processing, and they can also withdraw that consent at anytime, meaning that consent management needs to be granular (allowing many different forms of consent), dynamic (allowing consent to be withdrawn), and user friendly enough that data subjects are actually empowered to understand how their data is being used and to assert control over that use.

- This will, in many of ML’s most powerful use cases, make the deployment and management of these models and their input data increasingly difficult.

And to end this section, a quick note on a “right to explainability” from ML. This question arises from the text of the GDPR itself, which has created a significant amount of confusion. And the stakes for this question are incredibly high. The existence of a potential right to explainability could have huge consequences for enterprise data science, as much of the predictive power of ML models lies in complexity that’s difficult, if not impossible, to explain.

In Articles 13-15 of the regulation, the GDPR states repeatedly that data subjects have a right to “meaningful information about the logic involved” and to “the significance and the envisaged consequences” of automated decision-making. Then, in Article 22 of the regulation, the GDPR states that data subjects have the right not to be subject to such decisions when they’d have the type of impact described above. Lastly, Recital 71, which is part of a non-binding commentary included in the regulation, states that data subjects are entitled to an explanation of automated decisions after they are made, in addition to being able to challenge those decisions. Taken together, these three provisions create a host of new and complex obligations between data subjects and the models processing their data, suggesting a pretty strong right to explainability.

My view: while it is possible, in theory, that EU regulators could interpret these provisions in the most stringent way – and assert that some of the most powerful uses of ML will require a full explanation of the model’s inner workings – this outcome seems implausible. What’s more likely is that EU regulators will read these provisions as suggesting that when ML is used to make decisions without human intervention, and when those decisions significantly impact data subjects, those individuals are entitled to some basic form of information about what is occurring.

And therein ends of my coverage of Cannes Lions 2018.