For Part 1 click here

5 April 2018 (Paris, France) – A few years ago I was in Moscow to launch an e-discovery review, one of several “extreme e-discovery” projects my e-discovery unit has done over the last 8 years (more on those projects in a subsequent post) and while in Moscow I had an opportunity to chat with a cyber maven to whom I had been introduced during one of my trips to the Mobile World Congress. He drove me to an otherwise residential district of southwest Moscow, to a twenty-story gray-and-white high rise, surrounded by a modest fence, which at first glance could be mistaken for an average apartment block. But there was something odd about the building: only twelve of the floors had windows.

This building is the heart of the Russian Internet phone station … the building is called “M9” … containing a crucial Internet exchange point known as MSK-QC. Nearly half of Russia’s Internet traffic passes through this structure every day. I was told that yellow and gray fiber-optic cables snake through the rooms and hang in coils from the ceilings, connecting servers and boxes between the racks and between floors. Most interesting? Google rents an entire floor on M9 to be as close as possible to the Internet exchange point of Russia. Each floor is protected by a thick metal door, accessible only to those with a special card.

Oh, yes. Almost forgot. On the eighth floor is a room occupied by the Federal Security Service, or Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopamom, or the FSB, the main successor organization to the KGB. The FSB’s presence is evident on all the floors. Said my source:

Scattered among the communications racks throughout the building are a few electronic boxes the size of a video player. These boxes are marked SORM, and they allow the FSB officers in the room on the eighth floor to have access to all of Russia’s Internet traffic. SORM stands for the Russian words meaning “operative search measure”. But the words imply much more [note to readers: I will have more about SORM in my concluding Part 4 of this series].

“Let’s fast forward to 2017”

Last year there were two very notable events in the annals of Russian cybersecurity and cyberspace:

- Massive protests against alleged corruption in the federal Russian government took place simultaneously in many cities across Russia, leading to the jailing of Alexei Navalny, a Russian lawyer, political activist and politician whom many (inside and outside Russia) is deemed to be “the man Vladimir Putin fears most”

- A bomb blast on a St Petersburg metro train killed 11 people and wounded dozens more, with the Western intelligence community framing the issue in a way that suggested Putin and the Federal Security Services could have been behind the attack, a not irrational idea.

I was in Moscow … again … during part of that period but for an unrelated event: Moscow has spent huge amounts of money and political capital to effect smart digital technology to join the “smart city” rage across the world: sensor networks for street lights, parking, waste disposal and so on, and a lot of underlying digital processes. Due to my ongoing work at and coverage of the Mobile World Congress (noted above), I had been invited to a “smart city” tour of London, followed by a similar tour in Russia to understand how Moscow differs from a city such as London which has a roughly comparable metro area population.

But I also took some time to chat once again with a few “cyber friends” and political associates and I focused on one element: how could a system, so astute in its recent antics on the world stage, brilliantly exploiting information-age tools to confuse audiences about what is truth, what isn’t, and setting their own narrative … miss such widespread organized protest?! Did somebody miss the email?

“So it’s time for a little history”

At its simplest, the story of how Russia won the (first) Russo-American cyberwar is because Obama did not fight back and failed to protect America’s democracy from Putin’s well-orchestrated, wide-ranging cyber assault. Obama’s maddening naiveté … manifesting hardly for the first time during his presidency … demonstrated how poorly he understood his adversary, and unsurprisingly, Putin was thereby emboldened on so many fronts.

Well, that and not understanding the Russian dynamic. At the European Electronic Warfare Symposium two years ago, one of the best presentations was by Dr. David Stupples, director of the Centre for Cyber Security Sciences at City University London. He made several points but here are the key ones from the presentation:

- Russia’s intelligence services decided years ago to make cyber warfare a national defense priority. They have become increasingly proficient in cyber operations as a result.

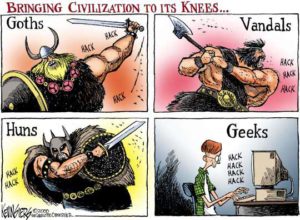

- From around 2007, Russia decided that information warfare was key to winning any world conflict, and that it was this area of capability and technology they decided would benefit from vastly increased military investment. What made this decision easier was that Russia was also home to the largest number of the world’s best hackers.

- The U.S. Democratic National Committee (DNC) attack was obviously not a high-value military target but it served a threefold motivation to hack its system: (i) demonstrate that Russia is on top of its game in this kind of shadowy warfare; (ii) embarrass the Democrats and undermine the presidential election process; and (ii) test U.S. security measures.

- This testing goes on all the time. Testing U.S. defenses would reveal to Moscow how Washington might react in response to further provocations. The goal of testing U.S. security measures is not now, nor has it in the past, proved to be a difficult objective for Moscow. The National Security Agency and FBI have both admitted that Russia had penetrated a significant number of sensitive U.S. infrastructure systems in order to test efficacy and document structure. I would surmise also to steal military secrets.

Read any of the major defense/cyber security journals … for example, Defense One or The Cyber Brief … and you come away with a key point: Russia’s cyber warfare activities are not just random disruption or embarrassing revelations. What Russia is doing is linking cyber attacking and hacking with its open information warfare methods … propaganda disguised as news programming, funding of NGOs, etc., etc. … and in coordination with its military establishment’s use of electronic warfare.

By employing all three methods together in an integrated pattern of activity Moscow can achieve what its military theorists call “reflexive control” – in other words warping your adversary’s perceptions to the point where that adversary begins to unknowingly take wrong or damaging actions.

Worse, as noted by a presenter last week at a NATO cyber intelligence workshop, the U.S. military and U.S. spy agencies, law enforcement, and diplomatic corps all have roles in “cyberwar” but they also have limiting boundaries. This necessitates handoffs and generates turf battles between the organizations and within them:

The Russians are in an opposite position: they excel in information warfare because they seamlessly integrate cyber operations, influence, intelligence, and diplomacy cohesively; and they don’t obsess over bureaucracy; they employ competing and overlapping efforts.

And Russia also has a distinct advantage in the cyber realm because on a regular basis it engages the services of non-governmental cyber crime entities, which masks its role in cyber attacks. This is what the U.S. and others do not do – engage proxy cyber warriors. This is not to say we never use them. But as explained to me by Linda Nowak of Crowdstrike:

[A brief note about Crowdstrike: it was their analysis of the code and techniques used against the DNC which led them to report that the DNC strike resembled those from earlier attacks on the White House and the State Department that led them to identify not one but two Russian intruders, names you have all heard repeatedly in the media: Cozy Bear, which is believed to be affiliated with the FSB, Russia’s answer to the CIA; and Fancy Bear, which they had linked to the GRU, Russian military intelligence.

At the NATO cyber intelligence workshop I noted above, one presenter said NATO believes there are currently more than one million Russian programmers engaged in cyber crime. These programmers are affiliated with at least 40 Russian-based cyber crime rings, as well as official government entities. The United States and its partners could not feasibly match this level of manpower using only government agencies and employees.

So let’s be very clear: Russian spies did not wait until the summer of 2014 (the earliest date mentioned by the Senate investigation committee investigating Russian hacking last fall) to start hacking the United States. This past fall, in fact, marked the twentieth anniversary of the world’s first major campaign of state-on-state digital espionage. There are a lot of detailed histories published on this period, so the following section highlights just a few major points.

“A short history of Russian attacks on the U.S.”

In 1996, five years after the end of the USSR, the Pentagon began to detect high-volume network breaches from Russia. The campaign was an intelligence-gathering operation: whenever the intruders from Moscow found their way into a U. S. government computer, they binged, stealing copies of every file they could.

By 1998, when the FBI code-named the hacking campaign “Moonlight Maze”, the Russians were commandeering foreign computers and using them as staging hubs. At a time when a 56 kbps dial-up connection was more than sufficient to get the best of Pets.com and AltaVista, Russian operators extracted several gigabytes of data from a U. S. Navy computer in a single session. With the unwitting help of proxy machines – including a Navy supercomputer in Virginia Beach, a server at a London nonprofit, and a computer lab at a public library in Colorado – that accomplishment was repeated hundreds of times over. Eventually, the Russians stole the equivalent, as an Air Intelligence Agency estimate later estimated, of “a stack of printed copier paper three times the height of the Washington Monument.”

Attacks have continued at a very brisk pace ever since.

One of the key points made this year at the Munich Security Conference was that Russia is extremely patient, playing the long game, more so than their American counterparts, when it comes to espionage. Rob Richer, former CIA Associate Deputy Director for Operations and formerly chief of Russian Operations, has often noted that when he was chief of Russia operations from 1995 to 1998 it was at a time when the CIA was catching Russia’s long term penetrations of the CIA, of the FBI, of NSA, and of the U.S. military. (There are numerous books that cover this period; email me for a bibliography). Richer noted some of those people were developed over time:

The Russians have no problem looking five, ten years down the road. The U.S. government tends to look at things in two to three year windows.

Richer gives this example: a CIA case officer arrives at a new station. His job is to recruit spies; he recruits them. That’s where he gets his credit. He turns them over to someone else. The handler doesn’t get as much credit as the person who has recruited the spy. The CIA is continually turning people over and looking for short-term gains. Whereas the Russians will have someone handle a guy for 10, 12, 15 years. The CIA keeps bumping into the same Russian case officer.

But this “short-termism” is embedded in American political culture (and, frankly, everything else). Americans live in political cycles and in assignment cycles. Every four to eight years, we have a new presidency. If you look at Congress, you look at the Senate, you look at Intelligence Oversight. There’s a high rate of turnover. And in the CIA you get a new director every administration. Each time, they have a different agenda.

When the Russians put someone in charge of an intelligence service he stays for more than a decade.

Yes, technology and staffing and the ability to manipulate the web and develop hacking skills – that’s been modern intelligence history over the last 10 years. That has been the game changer. But what did we do? The Western intelligence community spent billions to spy on everyone, while Russia stayed focused. The West turned into what it previously despised and feared – a surveillance state – while Russia stayed focused on getting their ducks in line: further developed their human intelligence assets, further developed their targeted cyber-ops capability, showed off their developed weaponry in Syria, in Ukraine, etc.

And Putin made brilliant use of old and new forms of propaganda to exploit political divisions. The leading element of this has been RT (Russia Today) which is not only one of the most widely watched (and heavily subsidized) global sources of state television propaganda (which claims 70 million weekly viewers and 35 million daily) but a vast social-media machinery as well. Added to its hidden influence is a vast network of Russian trolls – agents paid to spread disinformation and Russian propaganda points by posing as authentic and spontaneous commentators.

“So, where are we today?”

In my concluding Part 4 of this series I will add some depth to the issue of where the U.S. is today vis-vis Russia cyberattacks, why the West is so weak against Putin, and why we are such as easy mark. But a few points vis-a-vis history:

- We always, always, always make the mistake of treating Russia as if it were backwards. Russia wants to be an equal world power, if not the world power. Putin in many ways thinks like a Czar. He wants that authority. He wants that control. So he sets a goal to be able to influence things in the United States, whether politically, using firms to lobby or through business deals, or “cyber games”. This is so bloody obvious. The Kremlin’s geopolitical strategy depends only on fractures … not domination. They cannot and do not “conquer” adversaries. They simply fragment their opposition, for which extremists are ideal. It’s what they’ve done in the US & EU.

- Look at Syria. Does Putin really care about Syria? Does he really care about Crimea/Ukraine? Of course not. Does he care about being a main player in the Middle East and showing that he has the clout to push the U.S. back? Yes, and that’s what he’s done. Look at Ukraine. This is more about the politics of presence and influence, than about the politics of actually what happens.

- The U.S. is now a step back … far back. It must now accelerate its intelligence gathering on Russian intentions. That is the hardest intelligence to collect. It has to actively recruit target officers, who have understanding of intent against America. Since 9/11, the focus has been on combatting terrorism. We flooded Afghanistan with officers, then reduced them. We flooded Iraq with officers, then reduced them. EVERYTHING was flavored by what was happening across the Middle East.

- And as far as Putin’s aggression inside Russia I will quote Irina Morgana (co-author of The Red Web, the definitive text on Russia cyber prowess):

Russia did not need to be as repressive or technically sophisticated as, say, China. Putin did not need to carry out mass repression against journalists or activists; he could get results just as effectively by using the tools of threat and intimidation, which is what he did. He carried a big stick, but he didn’t always use it. Putin could be remarkably effective with the threat of the big stick. Russian Internet freedom has been curtailed. The thriving Internet companies, many of them starred in Russia from scratch in an environment of a free and open Internet, agreed to work under state censorship without creating much of a fuss. When invited to talk to Putin, they were so intimidated that they avoided raising the issue of sustaining Internet freedoms. They twisted arms more often than they cut wires.

But on this last point, internal suppression, my Russian friends tell me to keep in mind one dynamic, one transformation. In a crisis a tidal wave of content is generated and shared in real time. A single message can be copied by millions, and here the Putin system of control cannot cope. It is built to zero in on a few troublemakers, not millions of average users. In times of instability it is average users who spread the information, and the Putin system then breaks down. Which is why the Russian intelligence apparatus missed the surge of protests noted at the beginning of this post.

Quoting another Russian source:

The Internet today is the printing press of the past. Just as the invention of a printed page once enabled a free flow of ideas, so now simple tools like VKontakte [a massive Russian social network] and Facebook, widely used every day by average people in Russia, have created an environment in which information cannot be stopped.

All I could think of was that classic book by Christopher Hill “The World Turned Upside Down” about the Civil War in England, a work devoted to the radical thinkers of the time. Hill explained why the Revolution caused such a flow of radical ideas. It was pretty much that the extensive use of the press made it easier for eccentrics to get into print than ever before or since. The point Hill made was publishing had not yet developed into a capitalist industry, a capitalist tool.

To my Russian friends, today, for them, the Internet is the “everyman’s platform”. To control it, Putin would have to control the mind of every single user, which simply isn’t possible. Said Irina:

Information runs free like water or air on a network, not easily captured. The Russian conscript soldiers who posted their photographs taken in Ukraine … the death, the destruction, the subterfuge, the Russian “unmarked” soldiers marching into Crimea … all posted on VKontakte … did more to expose the Kremlin’s lies about the conflict than journalists or activists. The network enabled them. You had all of these inexperienced young men, boasting of their exploits, bragging to their families what they had done. With photos.

Coming in Part 3

The bugging, interception, and technical surveillance operations of the Russian intelligence services are impressive. Some of their developed technology is astounding. For instance, they can intercept a human voice from the vibrations of a window. I am sure Western intelligence is just as innovative but I was bowled over by some of the Russian surveillance technology out there.

As noted, Russia has spent decades tinkering with doctrines related to “information warfare”. I ended Part 1 of this series with a fascinating presentation made in in 1997 by Vladimir Markomenko, then deputy director of FAPSI (then the signals intelligence agency and NSA equivalent) and outlined in Alex Klimburg’s book. Markomenko defined the Russian view of “information war” along four dimensions:

- information warfare-electronic warfare

- intelligence

- hacker warfare, and

- psychological warfare

All were put on display in Russia’s conflict in Ukraine nearly twenty years later, and in the EU over the last few years. In Part 3 we are going to see Markomenko’s presentation in action.