For Part 1 (my initial thoughts) click here

For Part 2 (some more background, and the EU sounds off) click here

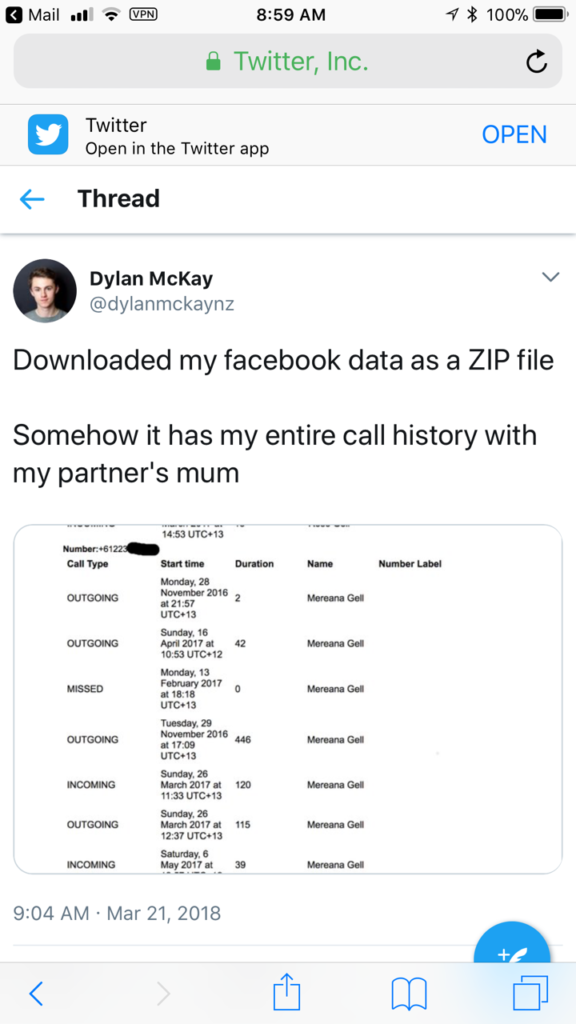

26 March 2018 (Geneva, Switzerland) – This past week, a New Zealand man was looking through the data Facebook had collected from him in an archive he had pulled down from the social networking site. While scanning the information Facebook had stored about his contacts, Dylan McKay discovered something distressing: Facebook also had about two years’ worth of phone call metadata from his Android phone, including names, phone numbers, and the length of each call made or received. He wrote about it on Twitter:

“All this slurping!”

As I have written in previous posts, it has long been understood by people in tech (less so in the broader public) that Facebook analysed users’ interactions in its Social Graph and collected far more data than publicly admitted, much of it escaping your “opt outs” and “control features”. However, when people started deleting their accounts this past weekend, the more sharp-eyed finely realized that Facebook was slurping more than they expected. What McKay and others saw was metadata for phone calls and text messages, even though they were sent with Android’s default phone and SMS apps, not Facebook’s Messenger apps (Apple iOS security seems to have protected Apple users from this slurping). The data slurp included Facebook app users’ interactions with others who are not on Facebook – meaning people who never gave Facebook permission for anything are probably profiled in its data troves anyway. This was already an issue for Web users, with the infamous Facebook cookie the subject of lawsuits in Belgium (Facebook won) and France (Facebook lost).

And just for interest, Google does the same thing with caller ID on Android, contacts lists, etc. You call people with an Android mobile, Google will know who you are, who you call, etc. — all without you ever giving Google permission. The tech companies have the opinion that data in contacts lists, caller ID, etc. is personal and therefore covered by a single end-user license agreement (EULA) signed up to by a single user. In fact it’s shared data, and in law the user agreeing to the EULA has to seek the permission of someone in their contact list before letting Facebook inside.

Plus, I am trying to imagine the process of specification, coding, testing, and deployment at Facebook and other firms – all of which were party to this implementation. It would have taken months and involved at least hundreds of individuals. And no one saw this as wrong, or in any way questionable.

The experience I described above was shared by a number of other Facebook users on Twitter, and I spoke with several and one even walked me through my own Facebook data archive. I will address these and other related points in more detail in Part 4 when I do a dive into the software code and process at play.

“Oh, yes. GDPR … the potential nothing burger”

This weekend all the EU tech forums were jammed with similar comments: “the GDPR will save us!” Well, maybe. Yes, the EU’s new GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) is on the books and comes into force May 2018 but it needs to be enforced. Last year I attended the annual meeting of the data protection officers of the EU institutions in Tallinn, Estonia. A smaller, informal one was held last week in Rome which I also had the opportunity to attend. The concerns voiced at both events were the same: “boy, we are all understaffed to enforce this thing!!” That was clearly the impetus behind the Commission coming up with money to assist member staffing (“no where near enough money” said a member state DPO at CPDP in January. “We do not have anywhere need a sufficient budget to add more people to handle GDPR and 1.7 million spread across 27 member states is peanuts”). This issue of lack of staff has also been a comment also made by a number of law firms and in-house counsel at several GDPR events I have attended.

Legal technology vendors and law firms have focused on the hefty fines imposed by GDPR if they break the law. That is their job … to scare the bejesus out of you so you buy their services. But many law firms have noted the glaring ambiguities in the law and intend to take advantage. Their public face is “concerned, it’s a big deal”. And no doubt you should be doing … well, something … to prepare for GDPR. More in a subsequent post.

But the “private” face the law firms wear behind closed doors is to tell clients they can litigate the hell out of it and delay enforcement. At least for the ones that can pay the big bucks. They know the regulators simply don’t have the staff to deal fairly with each case so they expect regulators will target “symbolic cases” and that some of that enforcement will be arbitrary and unfair — and ripe for litigation. This past November in Washington, D.C. (and earlier this year in Brussels) two law firms outlined their potential “attack mode” for fighting a GDPR action, and to delay enforcement. Said one lawyer “listen, all the Big Dogs are doing this. Nobody is going to roll over”.

For many DPOs it will fall to the infamous Max Schrems (yes, him) and the new organizations being formed. As I noted in a previous post, the GDPR codifies the right of consumer associations to sue for breach of data protection law. Max Schrems has formed one such organisation (heavily funded) and there are scores being set-up.

NOTE: Max is appearing this week at the IAPP’s Global Privacy Summit 2018 in Washington, D.C. and we have a video interview scheduled with him.

And at the end of the day, many ask whether the Cambridge Analytica/Facebook imbroglio will now (finally) crimp the power of these technology behemoths. Let’s take a quick look at their power.

A GENERATIONAL SCALE WE HAVE NEVER SEEN BEFORE

“The numbers speak for themselves”

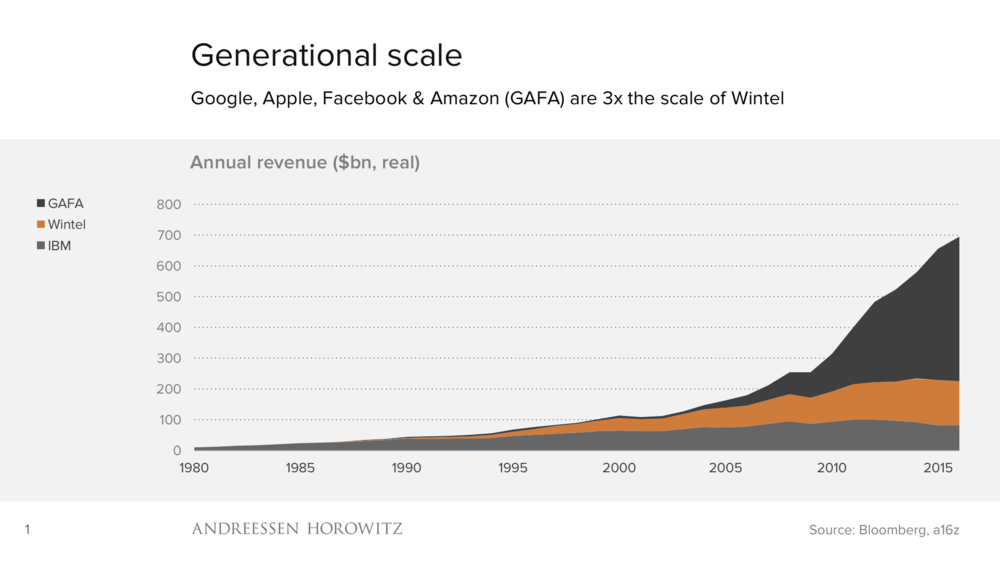

We all know, I think, that there are now far more smartphones than PCs, and we all know that there are far more people online now than there used to be. And I think we all know that big tech companies today are much bigger than the big tech companies of the past. It’s useful, though, to put some real numbers on that, and to get a sense of how much the scale has changed, and what that means.

A slide from a Andreessen Horowitz webinar this past fall puts this in perspective:

So, the four leading tech companies of the current cycle (outside China), Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon, or “GAFA”, have together over three times the revenue of Microsoft and Intel combined (“Wintel”, the dominant partnership of the previous cycle), and close to six times that of IBM. They have far more employees, and they invest far more. One can of course quibble with the detail of this – the business models are different and the global scale is different. But scale is scale.

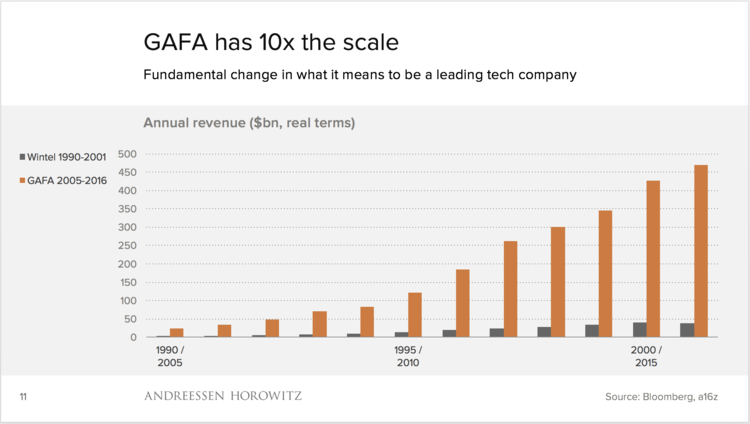

This change is even more striking if you compare the timeline. If you compare GAFA in their current dominance with Wintel in their period of dominance, you see not a 3x difference in scale but a 10x difference. Being a big tech company means something different now than in the past:

As the Andreessen Horowitz presenters said:

Scale means these companies can do a lot more. They can make smart speakers and watches and VR and glasses, they can commission their own microchips, and they can think about upending the $1.2tr car industry. They can pay more than many established players for content – in the past, tech companies always talked about buying premium TV shows but didn’t actually have the cash, but now it’s part of the marketing budget. Some of these things are a lot cheaper to do than in the past (smart speakers, for example, are just commodity smartphone components), but not all of them are, and the ability to do so many large experimental projects, as side-projects, without betting the company, is a consequence of this scale, and headcount.

And as for head count … internet firms employ fewer people per dollar of market value and concentrate those jobs mainly in thriving tech hubs. Techies’ tremendous wealth has made it easy to draw comparisons to last century’s robber barons. Consumers may benefit from their free products and from low prices, but small businesses have been hurt by the tech giants’ incursions into a wide array of industries, which can influence politicians. When I was at Cannes Lions last year (the advertising industry’s mega-conference as famous for its rosé-soaked yacht parties as its agenda-setting discussions and deals), I spent a good portion of my time with “mainstream advertisers” as well as GAFA representatives, and there was common agreement that Amazon has captured half of all dollars spent online, with Google and Facebook having captured virtually all the growth in digital advertising.

What had baffled me, though, was “how is this market big enough for four tech giants, not just one (Wintel) partnership?” Ben Evans, a partner at Andreessen Horowitz and the firm’s “go to guy” for all things mobile, put it in perspective this year at the Mobile World Congress:

What we have is four companies aggressively competing and cooperating with each other, and driving each other on, and each trying somehow to commoditise the others’ businesses. None of them quite pose a threat to the others’ core – Apple won’t do better search than Google and Amazon won’t do better operating systems than Apple. But the adjacencies and the new endpoints that they create do overlap, even if these companies get to them from different directions, and as consumers we all benefit. If I want a smart speaker, I can choose from two with huge, credible platforms behind them today, and probably four in six months, each making them for different reasons with different philosophies. No one applied that kind of pressure to Microsoft.

And Evans brought up another point, looking beyond the scale and the network effects — there’s a difference in character. Google, Facebook and Amazon are still controlled by their founders, and they’re aggressive street fighters. All of these companies have the benefit of twenty years more history – they saw what happened to Microsoft, and Yahoo, and AOL, and MySpace. So, they will disrupt themselves, and they will act. The shift to mobile was a fundamental structural threat that unbundled Facebook – Zuckerberg spent over 10% of the company to buy the most successful unbundlers and, as importantly, didn’t smother them after he’d bought them, unlike most large acquirers of disruptive companies.

I was reminded of Tim Cook’s famous admonition: “Disruption doesn’t work if everyone’s read the book, and everyone has”. This, to repeat, is compounded by scale, both for strategic shifts (such as chips) and for people: the big tech companies have hired the biggest proportion of the stock of academic machine learning/AI researchers in the last few years, paying huge (cash!!) salaries and offering both freedom and the chance to deploy something real to billions of people.

Evans made a comment (also reflected in the writings of Tim Wu, especially in his latest book The Attention Merchants) that both in tech and the broader economy, large, dominant companies don’t last. You lose the market or the market becomes irrelevant. Evans noted that Nokia had close to half of the mobile handset market a decade ago and lost it all; Wu noted that IBM still has the mainframe market but no one cares. Watson (despite all the “HURRAY! HURRAY! IT’S MARVELOUS” from the legal and medical communities) is a bust. That doesn’t mean Watson can’t help but as I have noted in numerous posts, the hype machine was on, full blast.

Few people can predict where the change will come from, but it does come. GAFA are very visibly conscious of that – Google experiments with everything, Apple is working on cars and mixed reality, and Facebook bought not just Instagram and WhatsApp but Oculus.

Paraphrasing Evans, there probably won’t be a technology that has 10x greater scale than smartphones, as mobile was 10x bigger than PCs and PCs were bigger than mainframes. But as we all know, there will be … something. It’s that never ending battle between those two infamous unfalsifiable points: “something will change, but we don’t know what” versus “nothing will change”. In tech, I know which side of that argument I find more likely.

“Oh, the political power”

Last fall the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee grilled the chief legal officers of Facebook, Google, and Twitter, an event that told us something we already knew: Russia manipulated the U.S. Presidential election results in 2016. We may never know the entire scale of the effort, or its total financial cost to the Russians (but new revelations on scale and cost seem to emerge every day), and perhaps it was not surprising that the Russians started as far back as 2010 given the Russians play the long game … but we pretty much knew the overall story.

The spectacle reaffirmed something else we knew, but had forgotten: industry self-regulation rarely works. From turn-of-the-century railroads, through energy markets in the 1990s, to the financial industry circa 2007, there are many examples that bear this out. The tech industry is only the latest case in point. That horse has left the barn … although many want to get him back in the barn (see below).

And, no, those lawyers sitting in the witness chair surely are not going to solve all those issues. Let’s park those thoughts of “ethical standards” at the curb. There is money to be made. The entire culture of these encrusted corporate in-house law departments and the law firms representing these companies are simply a professional trust that employs its skills to make sure their clients get what they want, the undermining of democracy be damned.

But that is also what hit me. The folks that should have been sitting in those chairs were Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Jack Dorsey – the founders of these companies, the guys behind the algorithms. The “enablers”. In fact, they were going to be there but Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, took on the role of negotiator (manipulator?) for the group and convinced the Senate committee that those guys were pretty busy and besides, most of these questions are legal so we’ll get the legal officers together for you. Why her? Because she “walks the walk”. For 6 years she worked in Washington for Larry Summers who was then serving as Secretary of the Treasury under Bill Clinton, walking the halls of Congress. She knew the drill, the highways and byways, who to talk to, how to schmooze them.

What? These guys talk among themselves for a common defense? Well, you might have forgotten that (once) secret Silicon Valley “no-poaching cartel” they formed which was uncovered a few years back whereby they had agreed to stop robbing each other’s talent. Disclosed, a few fines paid, forgiven. That’s power.

But as I said, they were busy. Poor Jack Dorsey could barely squeeze out 4 hours at a magazine photo shoot that week.

The key, key take-away for me was how intimately involved these lawyers were with their companies business plans and operations, and the development and structure of the algorithms and platforms. It is why I scoff at these “AI and bias” presentations at legal conferences when the speakers and presenters tell us “what we must do” and the “ethics that must be employed”. That the big platforms must “become more transparent” and that “clearer standards are in place concerning the flagging and removal of destructive content”. Of course, no where on any of these panels will you find the lawyers for Facebook, Google, Twitter et al.

These days we hear of a backlash against Silicon Valley — that magical land out of which flowed knowledge, ideas and innovations that gave us almost-unthinkable powers to learn, to communicate, to transform our lives into exactly what we wanted them to be. Now? The products and services it sends out into the world are being called addictive, divisive and even damaging, and we raise the cry that instead of making the world better, they are making it worse. From shopping to travel to education and human relationships … a backlash the likes of which Silicon Valley has never seen. And yes, the notion that Silicon Valley’s best days are over is far from new – people have been predicting its demise ever since the advent of the microprocessor. It was going to be the oil shocks of the ’70s that were going to take it down, and Japanese competition was going to take it down, then India, and then China. Oh, the Dot Com bust would kills it, or Y2K, or the ’08 crash — just one thing after another.

Granted, I do see a shift. And that’s because of how deeply penetrated tech is in people’s lives. More on that in Part 6.

_________________________________________

Coming up in this series: Parts 4 – 6

In Part 4 …

The software code and process at play. All the “keys” associated with the wealth of our personal behavior data: every website we’ve been to, many things we’ve bought in physical stores, and every app we’ve used and what we did there, and what we’ve talked about.

In Part 5 …

A look at why we give up our privacy to Facebook and other sites so willingly, and some of the psychology at work. Cambridge Analytica found success and wealth by tapping into a rich seam of public anger. Christopher Wylie, the source for the UK investigation piece on Cambridge Analytica that exploded last week, summed up the mission:

“We exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles. And built models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons.”

In Part 6 …

A wrap-up of my key points. And why a “solution” to social media manipulation will always escape us. Tribalism, manipulation, and misinformation …. in America, all well-established forces in politics, and all predating the web. But something fundamental has changed. Quoting Ethan Zuckerman (an associate professor in the Practice at MIT Media Lab whom I have quoted him before) from his book Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection:

Never before have we had the technological infrastructure to support the weaponization of emotion on a global scale. We have crossed the Rubicon.

We are taking about technology colonialism and I will expound a bit on technology companies today and how their veneer of sovereignty has allowed them to literally “cultivate our culture”, work across borders, use dominant culture as a weapon, and wield so much power in the global economy.