31 October 2017 (Serifos, Greece) – America’s next election is just a year away, and the country is still picking up the pieces from the last one.

Starting tomorrow (three separate Congressional committees have set hearings over the next two days), lawyers from Facebook, Twitter, and Google will tell the US Congress and the public how their platforms were used by Russian accounts to spread fear, hate, and division before last November’s presidential vote. Basically these committees will ask: “So what role did YOU play in the corruption of the U.S. political system?” And mind you: these hearings are extensively choreographed public set pieces — each company has already had private meetings with Congressional staff, and neither side expects fireworks.

Well, there may be a few bombshells. According to the written testimony to be presented by Facebook General Counsel Colin Stretch, more than half of Facebook’s users in the United States were exposed to Russian attempts to sow discord before and after the 2016 presidential election. And Google will reveal for the first time that over a thousand videos were uploaded to YouTube by Russian trolls on 18 separate channels (The testimony is being aired live but I have two staffers on-site at the committees who have already obtained some of the written testimony; more to come).

Much remains on the line. After all, we are talking about the platforms … in private hands … that enable our shared culture these days. And that’s pretty much what’s on trial this week – our culture, and how we share it. And, yes, while they’re testifying in the U.S. what they’re saying will resonate from Europe to Africa to Asia, where local elections have been marred by foreign propaganda spread on social media, and ethic violence accentuated (more below).

We’re at the early stages of how the U.S. is grappling with how social media has been weaponized by a foreign government. The next step after companies try to publicly defend themselves should be the unsettling process of examining how your relatives, your neighbors, your high school classmates, and yes, even you yourself, might have been targeted or manipulated.

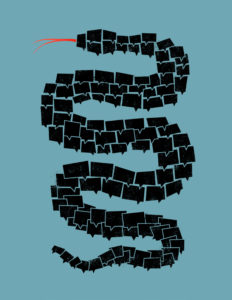

But to do that it is getting mighty difficult. These information giants are unilaterally “disappearing the evidence” as a colleague noted — pulling down whole pages and eliminating accounts linked to Russian users. When news organization have unearthed individual examples, social media companies are wiping them from the internet. Some members of Congress are pushing the companies to make these messages public, but they’re resisting. In the U.S., had this been a pending litigation, there is a concept called “legal hold” which is a process that an organization is required to use to preserve all forms of relevant information when litigation is reasonably anticipated. For the social media industry, they have no such restrictions. So they can wipe out the data with impunity. As one American lawyer told me earlier this month at a computational and information processing workshop in Germany “listen, if they were my client I would certainly tell them to delete/destroy everything. They need to protect their company from any possible litigation. That is first and foremost. That is what we are paid to advise”.

These companies are also hoping to avoid heavy regulation, by writing new rules themselves. Twitter said this week it would stop taking advertising dollars from Russian state media and identify who places candidate ads, and Facebook rolled out new political ad guidelines that also include who paid for the ad and identifying who they reached, and keeping an archive of federal election ads.

But this is all public relations bullshit:

- The majority of Russian-bought ads identified by Facebook and Twitter were ISSUE ads, focusing not on candidates but on divisive topics like race, refugees, immigration and gun control, and thus might not be affected by these changes. These ads are harder to define. There is currently no clear industry definition for issue-based ads. You would need companies, other industry leaders, policy makers, ad partners to clearly define them quickly and integrate them into the new Facebook/Twitter approach mentioned. Good luck with that.

- Twitter said it handed over 701 Russian linked accounts to Congressional investigators, which was a joke. Social media metrics investigators like Matthias Lufkens and Neil Rauhauser … using the same sophisticated technology Facebook, Twitter, etc. use for deep dive analytics … have identified 100s of thousands of Russian linked Facebok/Twitter propaganda accounts. NOTE: Twitter has “amended” its statement and will now tell lawmakers this week that it has “discovered” thousands of previously-undisclosed accounts tied to the Russian troll farm behind the Facebook campaign, according to my media team.

- In the UK, social media metrics investigators have identified a network of 13,000+ Twitter bots which pumped out a continuous scream of “pro-Brexit” messages in the run-up to the EU vote, all identified by media researcher Daniel Risberg as “Russian connected”.

- The Internet Research Agency, a so-called troll farm that has been linked to the Kremlin, amassed enormous followings for various Facebook Pages that masqueraded as destinations for discussion about all sorts of issues, from the Black Lives Matter movement to gun ownership. Aided by Facebook’s finely tuned ad-targeting tools, they were able to place posts in the News Feeds of users, looking like normal people. In one case, their stories were rebroadcast by Republican Party leaders in Texas because “they were Texans!!”

- Facebook says it will “tag” false news stories. As a Yale University study showed, the sheer volume of misinformation that floods the social media network makes it impossible for the fact-checking groups Facebook has partnered with – Politifact, FactCheck.org, Snopes.com, and others – to address every story. A study of the existence of flags on some – but not all – false stories made Trump supporters and young people more likely to believe any story that was not flagged.

- Moreover, alt-right groups are creating their own dialect, their own “wordspeak” to avoid being tagged on social media.

And irony abounds:

- In Myanmar, the rise in anti-Rohingya sentiment coincided with a huge boom in social media use that was partly attributable to Facebook itself. In 2016, the company partnered with MTP, the state-run telecom company, to pump up mobile purchases by giving subscribers access to its Free Basics program. Mobile use trippled. Free Basics includes a limited suite of internet services, including Facebook, that can be used without counting toward a cellphone data plan. Facebook users in Myanmar skyrocketed to more than 30 million today from 2 million in 2014. Facebook has become the de facto public square in Myanmar. And now violence against the Rohingya has been fueled, in part, by misinformation and anti-Rohingya propaganda spread on Facebook, which is used as a primary news source by almost everybody in the country. “Everything shared on the phone is regarded as true” said Cynthia Wong, a rights activist in Myanmar.

- The New York Times … that bastion of “freedom of the press” … found it necessary to set up a Tor account because many readers are technically blocked from accessing their website, or worry about network monitoring and online privacy.

- Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, apologized and vowed that the company would adjust its ad-buying tools to prevent similar problems in the future. She said “we never intended or anticipated this functionality being used this way — and that is on us.” It was a candid admission that reminded me of a moment in Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” after the scientist Victor Frankenstein realizes that his cobbled-together creature has gone rogue: “I had been the author of unalterable evils,” he says, “and I lived in daily fear lest the monster whom I had created should perpetrate some new wickedness.”

- “The Wall Street Angle”. As more than one analyst has said, there is limited financial incentive for companies to remove fake accounts. Executives fixated on user growth (or lack thereof) are focused on gaining and retaining new users, without much emphasis on deterring the fake ones. As one analyst told me: “I can make an argument that for all these companies, the user metric is probably the single most important data point investors focus on. The depressed Twitter share price is solely because of lack of user growth”. Last week, in fact, Twitter revealed it had “over counted” its user base – and its stock value tanked.

Yes, I know. Everybody is focused on the Russians and their use of artificial intelligence to game social media. But the sophisticated critiques of Facebook are not about ideas and content that people don’t like, but rather the new structural forces that Facebook has created. And Twitter. And Google. News and information flow differently now than they did before Facebook; capturing the human attention that constitutes that flow is Facebook’s raison d’être (and value to advertisers). Now that it has done so, Zuckerberg would like to pretend that his software is simply a “pure” conduit through which social and political truths can flow. The algorithms of click bait, echo chambers and adtech have their basis in BF Skinner’s “rat-in-the-box” experiments. Russia has merely taken advantage. They are far, far, far more expert than us. And the social media/news distribution structures in place go far, far beyond the ogre of AI.

The next test is coming fast: as one analyst at Politico told me “listen, there are 34 Senate seats and all 435 in the House up for grabs in November 2018. If you don’t think the Russians see a golden opportunity a-comin …”

THE NEW WARFARE: WAGED SEMI-OPENLY IN THE NEW PUBLIC SPHERE

OF CYBERSPACE AND SOCIAL MEDIA

We live in a complicated / fast paced / multidimensional era where cybersecurity and cyber machinations used to be a bit more arcane, but that have expanded dramatically based on Russian hacking (which has been going on for years), populism, and accusations that the White House has “colluded with the enemy!” In my research I read several old books (circa late 1980s, early 1990s) on “infowarfare” and “cyberwarfare” that predicted this very exotic age we are in, aspects of international intrigue and interrelations. Right on our doorstep. Which would have a massive impact on politics and government.

U.S. election integrity? Dead. Past history. The country will not recover. In fact, it is no longer a country but more a land of tribes, with multiple parties (not just Russians) who will influence all future elections. A few million dollars spent on the “wrong” messages (including antiwar stances, nonintervention, etc.) whereas hundreds of millions were spent on other influence campaigns including some veiled worship of the U.S. war machine.

Yes, Edward Snowden did us all one small favor, perhaps: he pulled back the curtain (a bit) so we now know the U.S has probably spent billions (exact figures are classified) on “psyops” or “psychological operations” against the enemy, many increasingly based in cyberspace. As I will detail in a future post in this series, the U.S. budget is possibly on order of five-to-six magnitude larger than that of the Russian operation … and no where near as effective as the Russians, it would appear.

The new warfare of the “now” and the future: waged semi-openly in the new public sphere of cyberspace and social media. We all know that propaganda is as old as warfare, and the first casualty of war is the truth. But now the new battleground is online and in peoples’ Facebook feeds.

In an attempt to get a grip on all of this, I and my team have spent the last year in Athens, D.C., Kiev, Moscow, Paris and Rome meeting with social media metrics analysts, ex-Facebook engineers, Russian trolls, “black hats”, and intelligence community contacts: working through this process, seeing and working with this technology, seeing how it is all done. It has been a mind-boggling journey. I was guided by the old proverb:

So let’s start first by looking at the awesome power of GAFA.

A GENERATIONAL SCALE WE HAVE NEVER SEEN BEFORE

We all know, I think, that there are now far more smartphones than PCs, and we all know that there are far more people online now than there used to be, and we also, I think, know that big tech companies today are much bigger than the big tech companies of the past. It’s useful, though, to put some real numbers on that, and to get a sense of use how much the scale has changed, and what that means.

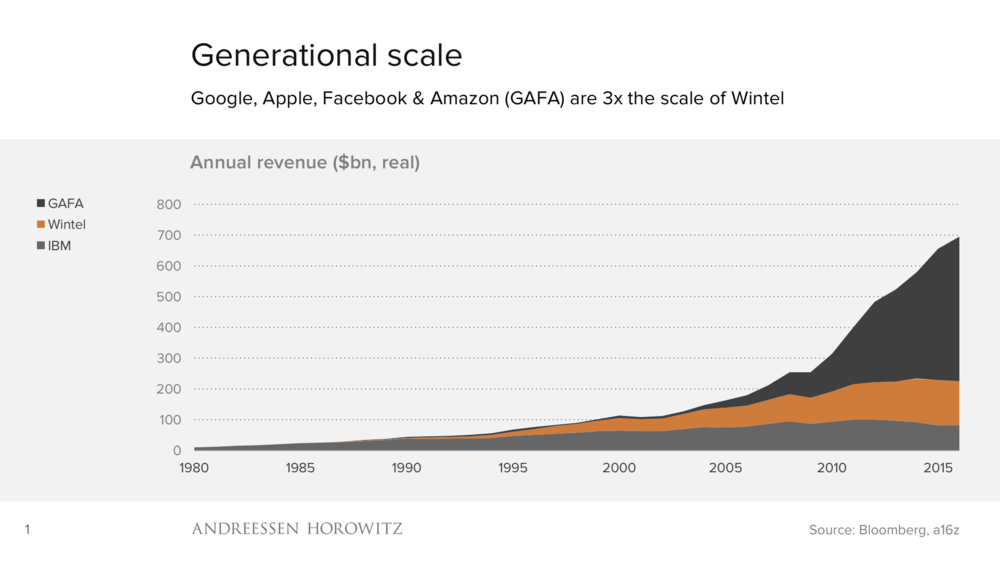

A slide from a recent Andreessen Horowitz webinar puts this in perspective:

So, the four leading tech companies of the current cycle (outside China), Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon, or “GAFA”, have together over three times the revenue of Microsoft and Intel combined (“Wintel”, the dominant partnership of the previous cycle), and close to six times that of IBM. They have far more employees, and they invest far more. (Once can of course quibble with the detail of this – the business models are different and the global scale is different. But scale is scale.)

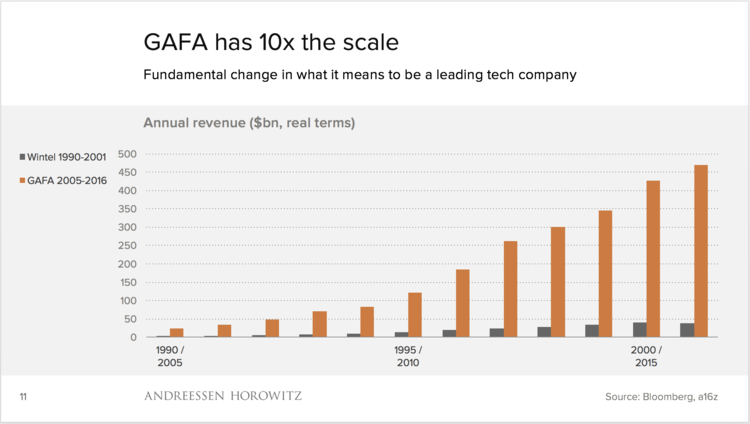

This change is even more striking if you shift the timeline. If you compare GAFA in their current dominance with Wintel in their period of dominance, you see not a 3x difference in scale but a 10x difference. Being a big tech company means something different now to in the past:

As the presenters said:

Scale means these companies can do a lot more. They can make smart speakers and watches and VR and glasses, they can commission their own microchips, and they can think about upending the $1.2tr car industry. They can pay more than many established players for content – in the past, tech companies always talked about buying premium TV shows but didn’t actually have the cash, but now it’s part of the marketing budget. Some of these things are a lot cheaper to do than in the past (smart speakers, for example, are just commodity smartphone components), but not all of them are, and the ability to do so many large experimental projects, as side-projects, without betting the company, is a consequence of this scale, and headcount.

And as for head count … internet firms employ fewer people per dollar of market value and concentrate those jobs mainly in thriving tech hubs. Techies’ tremendous wealth has made it easy to draw comparisons to last century’s robber barons. Consumers may benefit from their free products and from low prices, but small businesses have been hurt by the tech giants’ incursions into a wide array of industries, which can influence politicians. When I was at Cannes Lions this year (the advertising industry’s mega-conference as famous for its rosé-soaked yacht parties as its agenda-setting discussions and deals), I spent a good portion of the time with “mainstream advertisers” as well as GAFA representatives, and there was common agreement that Amazon has captured half of all dollars spent online, with Google and Facebook having captured virtually all the growth in digital advertising.

What had baffled me, though, was “how is this market big enough for four tech giants, not just one (Wintel) partnership?” Ben Evans, one of the presenters on the Andreessen Horowitz webinar, put it in perspective:

What we have is four companies aggressively competing and cooperating with each other, and driving each other on, and each trying somehow to commoditise the others’ businesses. None of them quite pose a threat to the others’ core – Apple won’t do better search than Google and Amazon won’t do better operating systems than Apple. But the adjacencies and the new endpoints that they create do overlap, even if these companies get to them from different directions, and as consumers we all benefit. If I want a smart speaker, I can choose from two with huge, credible platforms behind them today, and probably four in six months, each making them for different reasons with different philosophies. No-one applied that kind of pressure to Microsoft.

And Evans brought up another point, looking beyond the scale and the network effects — there’s a difference in character. Google, Facebook and Amazon are still controlled by their founders, and they’re aggressive street fighters. All of these companies have the benefit of twenty years more history – they saw what happened to Microsoft, and Yahoo, and AOL, and MySpace. So, they will disrupt themselves, and they will act. The shift to mobile was a fundamental structural threat that unbundled Facebook – Zuckerberg spent over 10% of the company to buy the most successful unbundlers and, as importantly, didn’t smother them after he’d bought them, unlike most large acquirers of disruptive companies.

I was reminded of Tim Cook’s famous admonition: “Disruption doesn’t work if everyone’s read the book, and everyone has”. This, to repeat, is compounded by scale, both for strategic shifts (such as chips) and for people: the big tech companies have hired the biggest proportion of the stock of academic machine learning/AI researchers in the last few years, paying huge (cash!!) salaries and offering both freedom and the chance to deploy something real to billions of people. I will discuss this in greater detail in another post separate from this series.

Evans made a comment (also reflected in the writings of Tim Wu, especially in his latest book The Attention Merchants) that both in tech and the broader economy, large, dominant companies don’t last. You lose the market or the market becomes irrelevant. Evans noted that Nokia had close to half of the mobile handset market a decade ago and lost it all; Wu noted that IBM still has the mainframe market but no one cares. Watson (despite all the “HURRAY! HURRAY! IT’S MARVELOUS” from the legal and medical communities) is a bust. That doesn’t mean Watson can’t help but as I have noted in numerous posts, the hype machine was on, full blast.

Few people can predict where the change will come from, but it does come. GAFA are very visibly conscious of that – Google experiments with everything, Apple is working on cars and mixed reality, and Facebook bought not just Instagram and WhatsApp but Oculus.

Paraphrasing Evans, there probably won’t be a technology that has 10x greater scale than smartphones, as mobile was 10x bigger than PCs and PCs were bigger than mainframes. But as we all know, there will be … something. It’s that never ending battle between those two infamous unfalsifiable points: “something will change, but we don’t know what” versus “nothing will change”. In tech, I know which side of that argument I find more likely.

TECHNOLOGY COLONIALISM

In a separate post not related to this series I will expound a bit on technology companies today and how their veneer of sovereignty has allowed them to literally “cultivate our culture”, work across borders, use dominant culture as a weapon, and wield so much power in the global economy. I will address the vapid employment of antitrust law to block the tech oligarchs’ domination of key markets like search, social media, computer, and smartphone operating systems, an expansion of my “new new thing” post earlier this year. But first …

COMING IN PART 2:

NARRATIVES, DATA, SOFTWARE, NEWS EVENTS:

WHAT WE THOUGHT WE UNDERSTOOD WE ARE FORCED TO REINTERPRET

In the media world, as in so many other realms, there is a sharp discontinuity in the timeline: before the 2016 election, and after. Well, it certainly seems that way. Things we thought we understood – narratives, data, software, news events – have to be reinterpreted in light of Donald Trump’s surprising win as well as the continuing questions about the role that misinformation and disinformation played in his election. Yes, every component of that chaotic digital campaign has been reported on, everywhere. There are already six books out.

And mind you. I am talking about something beyond just our “reinterpretation”. We are faced with entities that can direct, control, shift, emphasise, highlight, downplay, amplify – basically own the space.

But Facebook’s enormous distribution power for political information has had a long history, with numerous episodes of how it has been “manipulated” well before the 2016 election. It just seems that 2016 really exposed the rapacious partisanship reinforced by distinct media information spheres, the increasing scourge of “viral” hoaxes and other kinds of misinformation that could propagate through those networks, especially the Russian information ops agency.

But before I get to the Russian Bear, I need to explain how Facebook’s mechanics (and Twitter, too) allowed the Russian operatives to reach far beyond just those people who followed their fake pages and account, how they infiltrated LinkedIn, online games, etc. It will underscore how those roughly 3,000 ads that Facebook disclosed in September (most analysts know there were a lot more) from the Russian pages were just one, very small piece of the puzzle.

Because it is also about how Facebook – in its essence an advertising company – became a media company, but never lost its structured indifference to the content on its site except insofar as it helps to target and sell advertisements. A version of Gresham’s law is at work, in which fake news, which gets more clicks and is free to produce, drives out real news, which often tells people things they don’t want to hear, and is expensive to produce. In addition, Facebook uses an extensive set of tricks to increase its traffic and the revenue it makes from targeting ads, at the expense of the news-making institutions whose content it hosts. Its news feed directs traffic at you based not on your interests, but on how to make the maximum amount of advertising revenue from you. As Zeynep Tufekci said in her recent TED Talk “we’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads”.