“Even if I am crushed into powder, I will embrace you with ashes” –

One of the last letters Liu Xiaobo wrote to his wife, Liu Xia

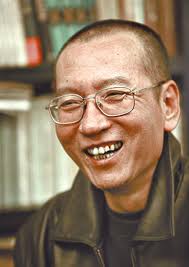

16 July 2017 – Liu Xiaobo, who died on July 13th at the age of 61, was hardly a household name in the West. Even in China he did not enjoy the status of a people’s hero at home. He was a brave and eloquent activist who had a significant following among Chinese intellectuals. But assiduous censorship of the domestic media, mixed with a feeling among many Chinese that dissidents are disloyal, combined to stifle his appeal. Repression continued even in death: news reports of his demise were blocked; even searches for his name were censured on China’s equivalent of Twitter.

Yet of those in China who have called for democracy, resisting the Communist Party’s ruthless efforts to prevent it from ever taking hold, Liu’s name stands out. His dignified, calm and persistent calls for freedom for China’s people made Liu one of the global giants of moral dissent, who belongs with Andrei Sakharov and Nelson Mandela — and like them was a prisoner of conscience and a winner of the Nobel peace prize.

And there is some irony here. In the late 1960s Mao Zedong … China’s “Great Helmsman” … encouraged children and adolescents to confront their teachers and parents, root out “cow ghosts and snake spirits,” and otherwise “make revolution.” In practice, this meant closing China’s schools. In the decades since, many have decried a generation’s loss of education.

Liu Xiaobo illustrates a different pattern. Said Perry Link (author of An Anatomy of Chinese: Rhythm, Metaphor, Politics):

Liu, born in 1955, was eleven when the schools closed, but he read books anyway, wherever he could find them. With no teachers to tell him what the government wanted him to think about what he read, he began to think for himself-and he loved it. Mao had inadvertently taught him a lesson that ran directly counter to Mao’s own goal of converting children into “little red soldiers.”

Liu rose to fame in literary circles with his literary critiques and he eventually became a visiting scholar at several overseas universities, his last in New York City.

While Liu was still in New York, the student movement in Peking continued to develop, not realizing that it was now set on a collision course with the hard-line faction of the Communist leadership – the faction to which China’s leader, Deng Xiaoping, was finally to give free rein. Liu was following the Tiananmen Square protests and sensed that a crisis would soon be reached, and he made a grave and generous decision: he gave up the safety and comfort of his New York academic appointment and rushed back to Peking.

He did not leave the square during the last dramatic days of the students’ demonstration; he desperately tried to persuade them that democratic politics must be “politics without hatred and without enemies,” and simultaneously, after martial law was imposed, he negotiated with the army in the hope of obtaining a peaceful evacuation of the square.

According to Werner Li (I will introduce him in a moment) thanks to Liu’s intervention, countless lives were saved, though in the end he could not prevent wider carnage – we still don’t know how many students, innocent bystanders, and even volunteer rescuers disappeared during the bloodbath of that final night. According to Perry Link (noted above) many believe it numbered in the hundreds. On orders of authorities, many unidentified bodies were secretly buried or burned. State-enforced amnesia suppressed immediately the entire atrocity with frightful efficiency.

Liu himself was arrested in the street three days after the massacre and imprisoned without trial for the next two years and again from 1995 to 1996 and he was imprisoned for the third time from 1996 to 1999 for his involvement in the democracy and human rights movement.

He died in a hospital bed in north-eastern China from liver cancer. The suffering endured by Liu, his family and friends was compounded by his miserable circumstances. Liu was eight years into an 11-year sentence for subversion. His crime was to write a petition calling for democracy, a cause he had been championing for decades. Though in a civilian hospital, he was still kept as a prisoner. The government refused his and his family’s requests that he be allowed to seek treatment abroad. It posted guards around his ward, deployed its army of internet censors to rub out any expression of sympathy for him, and ordered his family to be silent.

Liu may be the only Tiananmen protest leader to have published a book analysing the movement’s, and his own, moral failings, suggesting that China’s intellectuals had been blinded by self-righteousness and a grand sense of history-in-the-making. In reality, he wrote that:

the people recognised that in the Deng Xiaoping era (in contrast to the Mao Zedong era of class struggle), every effort was being made to develop the economy and raise the standard of living. This resulted in widespread and deep popular support and a solid, practical legitimacy. Indeed, the real failure of the 1989 movement was not only in the bloodshed and deaths, but also that it caused the Chinese government to tighten its grip on the nation and delay further reform. It interrupted the process by which the ruling Party was gradually democratising and reforming itself. The relaxed atmosphere of early 1989 was gone, replaced by an atmosphere of antagonism, tension, and terror.

Werner Li (German father, Chinese mother, born in China) is a long-time friend since our days as attendees at a MIT Media Lab event in 2005. He had introduced me to the writings of Liu who I had only known about through tangential references about the Tiananmen Square protests. When Li returned to China in 2010 to join what would become Baidu’s internal research lab called The Institute of Deep Learning, he not only kept me up to date on the progress of the age of intelligence in China but also why most Westerners didn’t have a clue how harshly and subtly censorship worked on an artist in China, whose talent, however prodigious, ultimately becomes docile and atrophied, to say nothing of what happens to critics. Li guided me through a plethora of Chinese source material (available in English) and Leigh Jenco of the London School of Economics provided sources from the Western perspective so that my Chinese political thought collection now numbers 72 books and 47 multi-media pieces. A treasure trove indeed.

A cynical game

Ah, that inconvenient question: how much perceived commercial advantage with China are you prepared to surrender to uphold values against the proliferation of Beijing’s illiberal order? The economic rise of China now dominates the entire landscape of international affairs. This fast transformation is rightly called “the Chinese miracle.” The general consensus, in China as well as abroad, is that the twenty-first century will be “China’s century.” International statesmen fly to Peking, while businessmen from all parts of the developed world are rushing to Shanghai and other provincial metropolises in the hope of securing deals. Europe is begging China to come to the rescue of its ailing currency.

Western governments have a long history of timidity and cynicism in their responses to China’s abysmal treatment of dissidents. In the 1980s, as China began to open to the outside world, Western leaders were so eager to win its support in their struggle against the Soviet Union that they made little fuss about China’s political prisoners. Why upset the reform-minded Deng Xiaoping by harping on about people like Wei Jingsheng, then serving a 15-year term for his role in the Democracy Wall movement, which had seen protests spread across China and which Deng had crushed in 1979?

But then the attitudes of Western leaders seemed to change in 1989 when Deng suppressed the Tiananmen unrest, resulting in hundreds of deaths. Suddenly it was fashionable to complain about jailing dissidents. And … as pointed out by Chinese political scholar Gu Jiazu and Western political scholar Gerald Segal … it also helped that China seemed less important when the Soviet Union was crumbling. From time to time the Chinese government would release someone, in the hope of rehabilitating itself in the eyes of the world. Western leaders were grateful. They wanted to show their own people, still outraged by the slaughter in Beijing, that censure was working. But it remained “business-as-usual”.

By the mid-1990s China’s economy was booming and commerce consigned dissidents to the margins once again. In the eyes of Western officials, China was becoming too rich to annoy. As noted in this weekend’s political blog of the Economist:

The world’s biggest firms were falling over themselves to enter its market. America, Britain and other countries set up “human-rights dialogues”—useful for separating humanitarian niceties from high-level dealmaking. The global financial crisis in 2008 tipped the balance further. The West began to see China as its economic saviour.

Earlier this month leaders of the G20 group of countries, including China’s president, Xi Jinping, gathered in Germany for an annual meeting. There was not a peep … not one peep … from any of them about Liu, whose terminal illness had been made known.

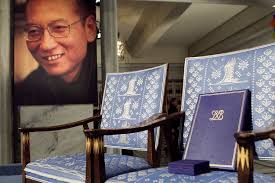

But, hey: why complain? China retaliates against countries that criticize its human-rights record. It restored relations with Norway only last year, having curtailed them after Oslo had hosted the Nobel ceremony in 2010 at which Liu got his prize (as China would not free him, he was represented by an empty chair).

Moreover, Xi is unlikely to listen. Before he took power in 2012 he scoffed at “a few foreigners, with full bellies, who have nothing better to do than try to point fingers at our country.” Point taken: China dismisses the west’s criticisms of its human rights record as little more than condescending lectures from countries that themselves have blood-spattered histories. In office Xi has ratcheted up pressure on dissidents and others who annoy the Communist Party, helped by new security laws. He is also embracing new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, which promise to monitor troublemakers more effectively (here).

Yet there are good reasons why Western leaders should speak out loudly for China’s dissidents all the same. For one thing, it is easy to exaggerate China’s ability to retaliate — especially if the West acts as one. The Chinese economy depends on trade. Even for little Norway, the economic impact of the spat was limited. For another, speaking out challenges Xi in his belief that jailing peaceful dissenters is normal. Silence only encourages him to lock up yet more activists. And remember that, for those who risk everything in pursuit of democracy, the knowledge that they have Western support is a huge boost even if it will not secure their release or better their lot. And I suppose a vital principle is at stake, too. As George Gao (a masters student I met at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in D.C. who is now at the Hopkins-Nanjing Center in China and whose writing has been published by Guernica Magazine, The Washington Post, The Guardian, etc.) noted in a recent piece in Foreign Policy magazine:

In recent years there has been much debate in China about whether values are universal or culturally specific. Keeping quiet about Mr Liu signalled that the West tacitly agrees with Mr Xi—that there are no overarching values and the West thus has no right to comment on China’s or how they are applied. This message not only undermines the cause of liberals in China, it also helps Mr Xi cover up a flaw in his argument. China, like Western countries, is a signatory to the UN’s Universal Declaration, which says: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” If the West is too selfish and cynical to put any store by universal values when they are flouted in China, it risks eroding them across the world and, ultimately, at home too.

The West should have spoken up for Liu. He represented the best kind of dissent in China. The blueprint for democracy, known as Charter 08, which landed him in prison, was clear in its demands: for an end to one-party rule and for genuine freedoms. Liu’s aim was not to trigger upheaval, but to encourage peaceful discussion. He briefly succeeded. The Communist Party’s censors and goons have stifled debate. Liu’s work is, sadly, done.

Today all we have are writers like Ha Jin, based in America, who has no need to toe the line, and has a freedom to hold the Chinese authorities and agencies to account … even if it’s only in the court of public opinion. Jin and others certainly get the measure of the relationship between America and modern China — the spendthrift sustained by the merchant who keeps extending him credit.

Reading Liu has been an eye opener for me, and not just for the politics. Culture and education really do leave permanent marks. Individual assertion against the group is mandated or discouraged by language, among other factors. I learned that the word identity is alien to the Chinese. It does not precisely translate into Chinese. When I was at the Frankfurt Book Fair two years ago I learned from Chinese translators that they can approximate it by stringing together several terms, each covering a part of the English word, like sameness and distinctiveness and status, but there’s no real equivalent. Liu speculated that the absence of this concept from the language indicates a deficiency in the awareness of self. Chinese also lacks a word for solitude as distinct from loneliness, as if there were no positive aspect to being separate from the group. It is a fascinating language.

And yes, the hypocrisy extends everywhere

The media obediently reports that U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson “works tirelessly” to resolve the crisis between Qatar and Saudi Arabia … the crisis that isn’t. Meanwhile, the Saudi siege on Yemen … provided by U.S. arms … is killing thousands of victims and has led to record levels of cholera, famine, and lack of aid in general. In both instances, the primary antagonists are the Saudis … creating the false Qatar narrative to keep us off the Yemen story … and Tillerson parrots their unsubstantiated concerns or remains silent over Yemen.

Now that the Trump administration has unequivocally hitched the nation’s wagon to Saudi Arabia and its Sunni Muslim allies, in its efforts to secure billion-dollar deals abroad, it has emboldened the Saudis, and the Al Qaeda and Islamic State branches that have exploited Yemen’s lawlessness to gain more ground. Said Richard Haas, president of the Council on Foreign Relations:

President Donald Trump’s sharp pivot toward Saudi Arabia has teed up a windfall for American industrial companies and investment firms, but his tacit approval of the kingdom’s military exploits may yet cost the United States. This deal has President Trump throwing gasoline on a house fire and locking the door on his way out.

Such is the way of all international politics, I suppose. Money is literally the alpha and omega. And the advent of a U.S. president comfortable in the company of authoritarian rulers has, sadly, reinforced the retreat of liberal democracy and allowed China and Saudi Arabia to pose as models for other nations.

Some excerpts from two of his essays

I have a copy of No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems which was published in English in 2011. It was edited by Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao, and his wife, Liu Xia, and has an incredible foreword by Václav Havel.

Apart from Liu’s essays dealing with injustices and various forms of criminal abuses of power, other articles address more general questions: for instance, the meaning and implications of the rise of China as a great power, still a matter of great uncertainty. The very rapid growth of a market economy and people’s increased awareness of private property rights have generated enormous popular demand for more freedom, and this ultimately might have an effect on China’s international position. On the other hand, the Communist government’s:

jealous defense of its dictatorial system and of the special privileges of the power elite has become the biggest obstacle to movement in the direction of freedom…. As long as China remains a dictatorial one-party state, it will never “rise” to become a mature civilized country ….

The Chinese Communists…are concentrating on economics, seeking to make themselves part of globalization, and are courting friends internationally precisely by discarding their erstwhile ideology.

At home, they defend their dictatorial system any way they can, [whereas abroad] they have become a blood-transfusion machine for a host of other dictatorships…. When the “rise” of a large dictatorial state that commands rapidly increasing economic strength meets with no effective deterrence from outside, but only an attitude of appeasement from the international mainstream, and if the Communists succeed in once again leading China down a disastrously mistaken historical road, the results will not only be another catastrophe for the Chinese people, but likely also a disaster for the spread of liberal democracy in the world. If the international community hopes to avoid these costs, free countries must do what they can to help the world’s largest dictatorship transform itself as quickly as possible into a free and democratic country.

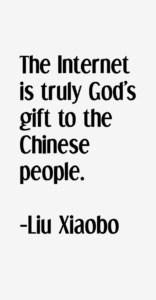

In an essay titled “To Change a Regime by Changing a Society” (which was cited as evidence against him in his criminal trial), Liu says:

The Internet in particular enables exchanges and diffusion of ideas in ways that largely escape government censorship; government control of thought and speech grows less and less effective. To become a free society, the only road for China can be that of a gradual improvement from the bottom up. This gradual transformation of society will eventually force a transformation of the regime.

However, in direct contradiction to such hopes, Liu also bleakly describes the spiritual desert of the urban culture in “post-totalitarian China.” The authorities, he writes, are enforcing a rigorous amnesia of the recent past. The Tiananmen massacre has been entirely erased from the minds of a new generation-while crude nationalism is being whipped up from time to time to distract attention from more disturbing issues. Literature, magazines, films, and videos all overflow with sex and violence reflecting “the moral squalor of our society”:

China has entered an Age of Cynicism in which people no longer believe in anything…. Even high officials and other Communist Party members no longer believe Party verbiage. Fidelity to cherished beliefs has been replaced by loyalty to anything that brings material benefit. Unrelenting inculcation of Chinese Communist Party ideology has…produced generations of people whose memories are blank ….

The post-Tiananmen urban generation, raised with prospects of moderately good living conditions [have now as their main goals] to become an official, get rich, or go abroad…. They have no patience at all for people who talk about suffering in history…. A huge Great Leap famine? A devastating Cultural Revolution? A Tiananmen massacre? All of this criticizing of the government and exposing of the society’s “dark side” is, in their view, completely unnecessary. They prefer to use their own indulgent lifestyles plus the stories that officialdom feeds them as proof that China has made tremendous progress.

An “erotic carnival” (Liu’s words) of sex, violence, and greed is indeed sweeping through the entire country, but — as Liu describes it — this wave merely reflects the moral collapse of a society that has been emptied of all values during the long years of its totalitarian brutalization.