A mashup of the week’s blogs/news and my thoughts

28 May 2017 (Palestine) — As Philip Stephens of the Financial Times blogged earlier this week, there was no linear connection between the events in Riyadh and Manchester — no obvious pathway between Trump’s speech to Arab leaders in the Saudi Arabian capital and the wicked act of terrorism at a pop concert in the north of England.

But you know what? For all that, we should feel uncomfortable with the coincidence. Yes, the perpetrators alone bear responsibility for murderous bombings such as that in Manchester. There is no room for “ifs” or “buts” or for spurious moral equivalence in such matters. As Stephens notes: “But it would also be a mistake to pretend that Islamist extremism is indifferent to the policies of western governments. And choosing sides in the Sunni-Shia conflict will only ensure safe spaces for jihadis.”

Yes, there is an enormous psychological religious element involved, too, and I will get to that at the end of this post.

But it boils down to what Stephens, and Kevan Malik of the Guardian, point out as the most basic: Manchester is the latest in the long line of indiscriminate attacks in European cities, a reminder that we cannot build walls against the world beyond. The murderer in this instance carried a British passport, but the inspiration for such acts is found in the raging fires of sectarian conflict in the Middle East. You cannot build borders so high as to stop the corruption of young minds by warped ideologies or halt the digital transfer of lethal know-how.

Some background to my involvement

I got involved in Middle East politics in a sort of a bassackwards way. I was in Tripoli, Libya in 2010 doing a data extraction project for a major e-discovery vendor. It was determined that the project would best be run by a Maltese national (I have Belgian, Greek and Maltese citizenship so that “fluidity” earns me many such assignments) given the strong ties between Libya and Malta.

As we all know, in December 2010, a Tunisian peddler set himself on fire. It was the talk of the entire Arab world, and beyond. Our data extraction project was cut short. The series of events that followed engulfed the Arab world at the end of the first and the beginning of the second decade of the twenty-first century. Some people called the process “the Arab Spring”. I preferred “the Arab Awakening” because it generated a powerful shift in the cultural, economic, political and social tectonic plates of the Arab world. The Arab Awakening took many people in the West by surprise. That fact intrigued me, and to a large extent rekindled my desire to revisit all of the Middle East history books I had read years earlier. Many would claim that the the Arab Awakening was responsible for the chaos in the Middle East. In my opinion, it would be more accurate to say that the Arab Awakening was the result of the chaotic situation that has prevailed in the Arab world, which was previously held in check by a thin layer of oppression and repression. The Middle East was a smoldering volcano; the Arab Awakening was the moment in time when that thin layer ripped open, and chaos exploded onto the surface with all its might.

Then in 2012 I began attending “DLD Tel Aviv”. It is Israel’s biggest tech conference but really much bigger than just a conference and properly referred to as an “Innovation Festival.” It is where the Big Dogs like Facebook, Google, IBM, Intel, Microsoft … even Coke, Disney and LL Bean … unveil some of their “work-in-progress” funky tech. It’s technology you will eventually read about first in an aViv paper, then the MIT Technology Review, and then the mainstream tech media. And it is a place to meet folks like Yossi Matias, the managing director of Google’s R&D Center in Israel and Senior Director of Google’s Search organization, and Aya Soffer, an IBM director behind Watson and IBM’s cognitive analytics programs. For my e-discovery/litigation technology readers, it was the place I first learned about the Google technology that can summarize documents and use machine-learning to produce and connect coherent and accurate snippets of text from other documents in a database.

And it is a trip sometimes bracketed by a small tech conference in Amman, Jordan.

Then one year I decided to add an extra 2 weeks to the trip, purely as a fact-finding event of my own in keeping with a personal educational agenda. There is an Italian phrase that describes the people (Arabs, Greeks, Italians, etc.) who populate the Mediterranean … “una faccia, una razza” (one face, one race) … that is far too simple an expression but meant to capture a similar set of values, religions, customs, food, etc. across the region. I spend most of my time in and around the Med but not enough in the core of the Middle East and that was my intent.

I traveled across Israel and all through the West Bank, eating/shopping/talking with people in Ashkelon, Haifa, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, etc. but also Hebron, Jericho, Nablus and Ramallah. I had a multitude of conversations with journalists, military intelligence experts, political pundits and just the “everyday” people I encountered who seemed to be careless of hardship and risk and invited me into their homes. They wanted to air out the brutal geopolitics involved, the powerful regional and international allies (and foes) that have acted with indifference.

I had even started some very basic Arabic and Hebrew language studies because if ever there was a place where language has dictated events, this is it. Forces have transformed “Palestine” from a homeland to a slogan. Much like everybody knows where America is, but nobody has ever been there, Palestine has become that quintessential illusion. Language truly dictates.

Down the rabbit hole …..

And the reason you need to speak with everybody, hear all the views and versions, is to build a “buffer” to protect yourself against personal agendas – because everybody here has one. So for a “base” I have tended to rely on sources that I find to be balanced. I think Ari Shavit’s My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, Ali Abunimah’s The Battle for Justice in Palestine, and Gaza: A History by Jean-Pierre Filiu (now in English) are the places to start. These books are brutally honest regarding both sides and are insightful, sensitive. I have had the additional opportunity to meet the authors or hear them in presentations.

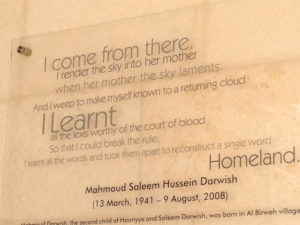

But you also need to read the works of poets and writers like Navit Barel, Mahmoud Darwish and Ghassan Kanafani, and read independent sources like Perspective Magazine.

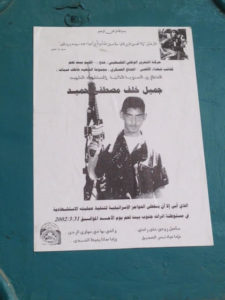

And … of course .. you need to hear about and learn about the brutality: how trained killers, with no political leanings, are paid 20,000 shekels ($5,300) to carry out attacks and murders. And how Palestinian youths are recruited to attack and kill, their faces plastered around East Jerusalem on posters hailing them as martyrs.

And the indiscriminate arrest and beating of Palestinians. Or how Palestinian novelists like Khalida Ghosheh are arrested and taken into interrogation. In her case, the subject matter was her forthcoming novel The Jackal’s Trap which focuses on Palestinian collaborators with Israeli occupation forces. The interrogators claim her novel poses a threat to collaborators working with the occupation.

It takes a lot of work. Why? Because even though I refer to the current situation as an occupation, one can observe the uniquely critical treatment Israel often receives from the media, NGOs, and European politicians. Why? Oh, simple, really. It is far easier to become outraged watching two radically different civilizations collide than it is watching or reading about Alawite Muslims kill Sunni Muslims in Syria, for example, because to a Western observer the difference between Alawite and Sunni is too subtle to fit into a compelling narrative. I mean, really: how in hell can you summarize THAT on Facebook or Twitter? And enrage your like-minded friends? One of my favorite computer visionaries, Douglas Engelbart, said it best when he opined digital tools can only “augment” human intellect … unless they go too far and kill off our deeper thinking.

Drawing that linear connection between the events in Riyadh and Manchester

This morning I watched or read Trump’s statements in his address to the assembled Arab autocrats in Riyadh. Not so long ago … I am pretty sure … Trump was declaring that “Islam hates us” and signing directives to bar travellers from several Muslim-majority countries. Maybe I missed something. Now, his message is that Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states should step up the fight against terrorism closer to home.

Cue up the familiar hypocrisies — sorry: the Trump team calls them “foreign policy realisms” — because what we have here is Trump, speaking in Saudi Arabia, the exporter of the extreme, Wahhabi brand of Sunni Islam that offers a theological underpinning for many of the jihadis around the world. Most of the murderers behind the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington in 2001 were Saudi citizens. Trump? no mention of any such connections. Nor of the repression and human rights abuses practised by his hosts. But he was there to sell US weapons systems — $110bn worth of them — and to attract Saudi investment into the US. It was all about “jobs, jobs, jobs”, he said. This administration, he promised, would never seek to meddle in the domestic affairs of its allies.

Side note: and the Saudis, great chaps they are, thanking Jarad Kushner for personally negotiating that sweet arms sales, promptly pumping $20 billion into the Blackstone Group. If you were not aware, since 2013, Blackstone has loaned more than $400 million to finance Kushner real estate deals, making it one of the business’s largest lenders. And their ties go beyond the loans. Stephen Schwarzman, Blackstone’s co-founder and chief executive officer, heads Trump’s business-advisory council and was in Riyadh with the president and Kushner. The Saudi investment drove the firm’s stock up more than 8 percent. Conflict? Nah.

My point is that what Trump has done is put the U.S. at the head of the Sunni Arab coalition against Iran. Why? Unable to unravel the international nuclear deal with Tehran, as he had promised, the president is set on uniting the Arab world — and Israel — against the Ayatollahs. The jihadis of ISIS may be Sunni, but to Trump’s mind responsibility for the sectarianism that disfigures so much of the region rests with Iran.

Sound familiar? Yep. We have been here before. Philip Stephens:

The U.S. backed Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in his 1980s war against Iran. A close relationship between Washington and the Gulf monarchies was long the default position of US policy towards the region. Barack Obama made the intelligent judgment that peace in the region — and eventual victory over the extremists — demanded some sort of accommodation between Saudi Arabia and Iran as the principal Sunni and Shia powers.

And quoting Sam Parker of the Guardian in a recent blog post:

In securing the nuclear deal with Iran, Obama adopted a balanced approach calculated to draw Tehran back into the international community. Trump prefers to pour fuel on to the sectarian flames.

Iran cannot be excused its role in propping up Bashar al-Assad in Syria or deploying its proxies to destabilise Sunni regimes elsewhere. Few would describe it as a paragon of freedom and the rule of law — unless, perhaps, they were drawing comparisons with Saudi Arabia or Egypt. It has, however, been moving, crab-like, towards something like democracy. As Trump was being feted in feudal style, Iranians voted to defy their own theocracy by backing the reformist Hassan Rouhani for a second term as president.

The … West … just … does … not … get … it. The US and its western allies should have learned long ago that they cannot “fix” the Middle East. Bush and Blair believed they could transplant western democracy at the point of a cruise missile. The present violence in Iraq and Syria attest to their error. But nor did backing the Arab autocrats work. Repressive regimes provided the incubators for violent Islamism. We should not expect things to be different in future. Sam Parker:

The West should at least direct itself to the avoidance of harm. Of two things we can be certain. However much high-tech military hardware they buy from the US, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states cannot defeat Iran; and for as long as Riyadh and Tehran fight a Sunni-Shia war, there is no prospect of a regional settlement that would deny safe spaces for jihadis.

So back to Manchester. None of us can imagine what was in the mind of Salman Abedi — the Manchester bomber — as he set off the bomb that killed and maimed young children and their parents in their innocent enjoyment of an evening out. We think we can guess because the Guardian and the Financial Times have done an excellent job on several in-depth pieces on how the Manchester attack has put a focus on a failed state whose troubles have been overshadowed by Syria – Libya.

The Times has run several excellent pieces on how Abedi returned to Libya to reunite with his father, who had left his family in Manchester three years earlier to aid the revolution against Gaddafi, and had come to fight Gaddafi. He was not alone. As the articles detail, it was 2011, and dozens of other Mancunians were already there. Mustafa Graf, the imam of the Didsbury mosque, the centre of the Libyan community in south Manchester, had also travelled back to Libya to help topple Gaddafi. Manchester became a fundraising centre for their war effort. Preachers travelled between the two countries, encouraging the fight, invariably couching it in terms of jihad.

One thing I learned from a military intelligence contact this weekend was this: security officials have repeatedly sketched out the dangerous dynamics the Syrian crisis has unleashed: a cohort of young Britons who will be brutalized by the conflict, skilled in the trade and tools of war, connected to transnational networks of fellow fighters by powerful bonds of kinship and shared suffering. He said it is a prognosis that holds true for the civil war in Libya:

Listen: the story of Salman Abedi is one of a parallel, overlooked jihad to that in Syria. These are fundamentally questions of identity. What are the local grievances that would lead someone to blow up a load of young people at a concert with nails and bolts? Manchester isn’t the city that made those grievances fester and grow, It’s the ability of groups like ISIS to wrap up your individual and local anxieties and grievances into this overall huge picture — to make you a somebody.

Yes, yes, yes. What we know is that the only way to respond to such outrages is to remain resolute at once in the fight against the perpetrators and in safeguarding the liberal democratic values they seek to destroy. But Jesus, God … you can be pretty damn sure that taking sides in a sectarian power struggle will only defer the eventual defeat of extremists. What is hell is the U.S. thinking?! Well, besides the money they can make, of course.

The ugly strain of misogyny in modern Islam

I still maintain that geopolitics will always be at the heart of all of this. But I would be remiss not to address the religious psychology of terrorism … one of the primary reasons of this week’s trip. I am here to focus on a series of studies and presentations on the psychological impact of considering an activity as sacred. In brief, these studies have found that those who denote a facet of life as a sacred place, who place it in a higher priority on that aspect of life, will invest more energy in it, and derive more meaning from it than happens with things not denoted as sacred. Denoting something as sacred appears to have significant emotional and behavioral consequences, maybe even if that something is a jihad or turning America into a Biblical theocracy, or restoring the boundaries of Biblical Israel, or purifying the Hindu homeland, or converting the Tamils to Buddhism.

Thankfully, Janice Turner, who writes for the Times and other publications, has (almost) done my homework for me vis-a-vis Manchester. Earlier this week she blogged that she thinks the blinkered belief that foreign policy motivates terrorists ignores the ugly strain of misogyny in modern Islam. She noted that Ariana Grande, the performer at the Manchester concert, was famous and followed for her songs that screamed “I don’t need permission, I made my decision, to test my own limits.” The name of her tour is “Dangerous Woman”. Turner blogged:

No wonder flicking through “What’s On in Manchester” it caught Salman Abedi’s eye: to Islamists there is nothing more dangerous than a liberated girl.

And Jeremy Corbyn, as outlined in his speech on terrorism this week and this particular atrocity, which targeted women — 17 out of the 22 dead — believes all of this is a product only of Britain’s foreign policy, its irresponsible wars. In the barren, blinkered thinking of the unreconstructed left, Islam is blameless: fault can only lie with the West. Conveniently Corbyn forgets an ideological movement predating the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Salafism began in the 18th century but in the past 70 years has spread through Muslim populations, via mosques and madrassas funded by Saudi Arabia, crushing tolerance and diversity, proclaiming itself the one pure iteration of faith. Control of women is not a side issue, an unfortunate by-product, but the very heart of its mission.

She noted a story I had read long in a piece about the Muslim Brotherhood. Sayyid Qutb, the al-Qaeda philosopher, was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood who travelled the U.S. in the 1950s to work out how the Arab world could rebuild after suffering colonial defeats. He noted female carnality at church dances: “The American girl is well acquainted with her body’s seductive capacity. She knows it lies in the round breasts, the full buttocks, and in the shapely thighs, sleek legs. She knows all this and does not hide it.” Turner writes:

Sexuality, he concluded, was western, ergo unIslamic. Women’s freedom, both in the bedroom and to work beyond the home, was a sign of society’s degradation. Islam must rebuild itself upon the family; women must return to codes of obedience, piety and (above all) modesty, rooted in the age of the Prophet. When Isis or the Taliban roll into a town, shrouding women is their first act.

Islam has many diverse strands: joyful, liberal, tolerant, scholarly, even licentious. Salafism — a political credo — uses shame, threats and even violence to extinguish them all. You see its influence in every veiled woman in Tower Hamlets, or every Brummie girl shoved into a hijab aged five. Women from countries that never covered now feel compelled to hide.

For men, conservative Islam has huge attractions: it enshrines male dominance, at home or in the world, as God’s will. Jihad, its most extreme manifestation, is an exaltation of twisted, toxic, violent hyper-masculinity, like those too-frequent cases of divorced fathers who kill themselves with all their kids.

Before he drove a car into a crowd on Westminster Bridge Khalid Masood coerced his wife, Farzana, until she fled. Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, the Nice lorry driver who killed 86, beat up his girlfriends. Omar Mateen, who shot dead 49 in a Florida nightclub, would attack his wife if she hadn’t done the laundry.

Turner quotes a young British Muslim she met in Manchester who asked “Why doesn’t the left ever realize that these people are our far right?”

Why indeed?

Conclusion

Much, much more to say but the day grows short. Avi Arad, an Israeli military chum, told me a terrorist atrocity only works if it becomes something more than itself. He noted that Sir Lawrence Freedman, known as “the dean of British strategic studies” (or so it says on his Wikipedia page), wrote about this earlier in the week, parcelling his opinion across Facebook and Twitter so that many more people could see it (Freedman does not publish much). Freedman pointed out that an individual terrorist succeeds when his or her attack succeeds. But terrorism doesn’t succeed unless there are “regular attacks” which destabilize the whole of society. In that context “every attack prevented not only spares people misery but also undermines attempts to create a sense of a society under siege”.

Well, he’s right. That’s the ball to keep your eye on, if you can see it through the pain and tears. Avi says:

It’s a percentage game, for the most part. We have been at this stopping-attacks business for a long time now and the Brits have learned a lot since the London bombings of 2005. By and large (and the spooks and cops will tell you the same) we have the forces required, they have the powers they need and whatever they once were, they are sophisticated now. The remarkable thing is not that Salman Abedi “got through” but — given the variety of motivations and backgrounds of would-be jihadists and other kinds of terrorist — that more attacks don’t succeed.

Now, of course, we have been talking about the need for drastic online censorship or curbs on freedom of speech other than actual incitement to violence. The surveillance powers in the UK 2016 Investigatory Powers Act are … well, as far as I can see from the summaries, not having read the Act … proportionate and sufficient. But they do open the door to defeating terrorism by becoming an authoritarian state.

Counter-radicalization? Look, to put it at its simplest (and I am simply paraphrasing the excellent material on the Guardian and the FT sites I noted above) … we REALLY need the intelligence afforded by communities about their own members (“who’s up to what?”) and we need to interdict the ideological route that some take from ordinary beliefs to terrible acts. And as Ari says, the trick is to make sure that those two strands don’t act against each other. That has been an issue in the Israeli-Palestian-collaborator matrix. In short, we don’t want to risk losing vital intelligence by alienating folk, but we don’t want to allow the conditions that give rise to radicalization to go unchecked.