Shields up!!!

16 May 2017 (Brussels, Belgium) – This past weekend I published a post The “WannaCry” ransomware attack, cyber warfare … and the lack of understanding, an attempt to help readers understand the technology behind Friday’s attack and the issues involved. Now some further thoughts on blame, protecting yourself … and the business model we need.

Note: a big hat tip to “Ivan” (my blackhat buddy who helps me navigate the Dark Web) who advised “you don’t need me: YouTube provides its own platform for promoting and selling ransomware. Oh, the competition!!” (click here)

Hallelujah! A cyber attack! Ka-ching!

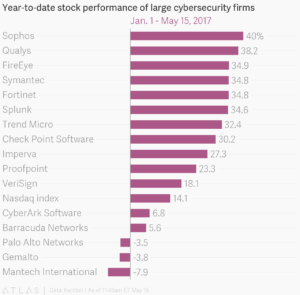

I can tell you one thing: the hackers who unleashed this ransomware attack may have made themselves over $42,000 in payments from victims so far (a calculation run last night by CISCO Information) but that is a paltry sum compared with the hundreds of millions in market value that cybersecurity companies around the world have gained since the attacks hit. Symantec jumped by around 4%, worth some $700 million in market cap. Companies like Fortinet, FireEye, and Qualys also jumped in the U.S. market. London-listed Sophos gained a chunky 8% in trading yesterday, adding $160 million in market value. Finland-based F-Secure and Tokyo-listed Trend Micro also added a few percent to their share prices, worth several million dollars for each company.

But it’s been a good year for cybersecurity stocks in general, with electoral hacks and high-profile leaks dominating the headlines. Cyber Cassandras have comfortably outperformed the Nasdaq composite index. A cybersecurity exchange-traded fund with the ticker HACK (naturally), was up by more than 3% in New York at the time of this writing. They have all had a pretty good run of late. Atlas – the charts and data unit of Quartz – published these nifty charts last night:

The “Blame Game” – Microsoft and the business model

As far as blame … well, as I noted in my piece over the weekend, everybody was all over the NSA. Microsoft President and Chief Legal Officer Brad Smith didn’t mince any words. On The Microsoft Blog he said:

Starting first in the United Kingdom and Spain, the malicious “WannaCrypt” software quickly spread globally, blocking customers from their data unless they paid a ransom using Bitcoin. The WannaCrypt exploits used in the attack were drawn from the exploits stolen from the National Security Agency, or NSA, in the United States. That theft was publicly reported earlier this year. A month prior, on March 14, Microsoft had released a security update to patch this vulnerability and protect our customers. While this protected newer Windows systems and computers that had enabled Windows Update to apply this latest update, many computers remained unpatched globally. As a result, hospitals, businesses, governments, and computers at homes were affected.

Smith mentions a number of key dates, but it’s important to get the timeline right. Lee Mathers, Ben Thompson and I did a drill down so let me summarize it as best as I understand it (the schedule outlined below, and links highlighted in red, provided by Ben Thompson who did a brilliant job searching for back-up):

- 2001: The bug in question was first introduced in Windows XP and has hung around in every version of Windows since then

- 2001–2015: At some point the NSA (likely the Equation Group, allegedly a part of the NSA) discovered the bug and built an exploit named EternalBlue, and may or may not have used it

- 2012–2015: An NSA contractor allegedly stole more than 75% of the NSA’s library of hacking tools

- August, 2016: A group called “ShadowBrokers” published hacking tools they claimed were from the NSA; the tools appeared to come from the Equation Group

- October, 2016: The aforementioned NSA contractor was charged with stealing NSA data

- January, 2017: ShadowBrokers put a number of Windows exploits up for sale, including a SMB zero day exploit — likely the “EternalBlue” exploit used in WannaCry — for 250 BTC (around $225,000 at that time)

- March, 2017: Microsoft, without fanfare, patched a number of bugs without giving credit to whomever discovered them; among them was the EternalBlue exploit, and it seems very possible the NSA warned them

- April, 2017: ShadowBrokers released a new batch of exploits, including EternalBlue, perhaps because Microsoft had already patched them (dramatically reducing the value of zero day exploits in particular)

- May, 2017: WannaCry, based on the EternalBlue exploit, was released and spread to around 200,000 computers before its kill switch was inadvertently triggered; new versions have already begun to spread

I like Microsoft. I have held the stock for years. I especially like Satya Nadella who took the reigns in 2014 and has radically changed the world’s biggest software firm in a very short time, putting at the heart of the new Microsoft Azure, a global computing cloud. It is formed of more than 100 data centres around the world, dishing up web-based applications, bringing mobile devices to life and crunching data for artificial-intelligence services. I will have more on this later this week in Part 2 of my series Predictive coding faces the dreaded S curve, e-discovery goes back home … and the cloud becomes SO important.

Yes, it is axiomatic to note that the malware authors bear ultimate responsibility for WannaCry. But I am going to lay some blame at the feet of Microsoft. Because the first thing to observe from this timeline is that, as with all Windows exploits, the initial blame lies with Microsoft. It is Microsoft that developed Windows without a strong security model for networking in particular, and while the company has done a lot of work to fix that, many fundamental flaws still remain.

Now, back off. I know. Not all of those flaws are Microsoft’s fault. Ben Thompson:

The default assumption for personal computers has always been to give applications mostly unfettered access to the entire computer, and all attempts to limit that have been met with howls of protest. iOS created a new model, in which applications were put in a sandbox and limited to carefully defined hooks and extensions into the operating system; that model, though, was only possible because iOS was new. Windows, in contrast, derived all of its market power from the established base of applications already in the market, which meant overly broad permissions couldn’t be removed retroactively without ruining Microsoft’s business model.

And full marks to Lee Mathers:

The reality is that software is hard: bugs are inevitable, particularly in something as complex as an operating system. That is why Microsoft, Apple, and basically any conscientious software developer regularly issues updates and bug fixes; that products can be fixed after the fact is inextricably linked to why they need to be fixed in the first place. To that end, though, it’s important to note that Microsoft did fix the bug two months ago: any computer that applied the March patch — which, by default, is installed automatically — is protected from WannaCry; Windows XP is an exception, but Microsoft stopped selling that operating system in 2008 and stopped supporting it in 2014 (despite that fact, Microsoft did release a Windows XP patch to Fix the bug on Friday night). In other words, end users and the IT organizations that manage their computers bear responsibility as well. Simply staying up-to-date on critical security patches would have kept them safe.

And ask any IT person: staying up-to-date is expensive, particularly in large organizations, because updates break stuff. That “stuff” might be critical line-of-business software, which may be from 3rd-party vendors, external contractors, or written in-house: that said software is so dependent on one particular version of an OS is itself a problem, so you can blame those developers too. The same goes for hardware and its associated drivers: there are stories from the UK’s National Health Service of MRI and X-ray machines that only run on Windows XP, critical negligence by the manufacturers of those machines.

The “Blame Game” – the government and the business model

In my post over the weekend I discussed the issue “Yikes!-The-NSA-leaks-like-a-sieve!” so no further comment on that. What is interesting is the screaming over the weekend that the NSA should hand over exploits immediately – in this case being, in effect, Microsoft’s QA team. But if that is the case, many argued, why would the NSA have any reason to invest the money and effort to find them? Well, the counter argument is not that the NSA should have warned Microsoft about the EternalBlue exploit years ago, but that somebody needs to be looking otherwise the underlying bug would have remained un-patched for even longer than it was (perhaps to be discovered by other entities like China or Russia; the NSA is not the only organization searching for bugs).

What I am more concerned about is what was argued last year in the context of the Apple and FBI imbroglio over phone encryption: government efforts to weaken security by fiat or the insertion of golden keys (as opposed to discovering pre-existing exploits). As Ben Thompson pointed out on his blog “given the indiscriminate and immediate way in which attacks can spread, the country that would lose the most from such an approach would be the one that has the most to lose (i.e. the United States).”

But even more important is the business model. Because after nearly two decades of dealing with these security disasters I posit: there is a systematic failure happening. Because the fatal flaw of software, beyond the various technical and strategic considerations, is that software – and thus security – is never finished. So this whole model of “payment is a one-time event” is simply ridiculous.

Which is why .. tada! .. “Software-as-a-service”, along with cloud computing generally (both easier to secure and with massive incentives to be secure), is the way we must go. This is exactly what is necessary for good security: vendors need to keep their applications (or in the case of Microsoft, operating systems) updated, and end users need to always be using the latest version. This is something constantly hammered home by technology Master Sensei like Andy Wilson and Sheng Yang of Logikcull.

To Microsoft’s credit the company has been moving in this direction for a long time. But more on that later this week. More importantly …

Protecting your digital life, your digital assets: what in hell can I do?

Quincy Larson, the founder of Free Code Camp (an open-source community for learning to code) has been collecting suggestions he finds useful for people to make their personal data more difficult for attackers to obtain.

David Koff and Bennet Madison focus more on corporations and have their own own “MUST DO / MUST NOT DO!” cybersecurity list.

So what I have attempted to do is compile all of those suggestions (many of these have been employed by myself and my staff) for your further consideration. I have not provided links to all of the apps and solutions (links are bolded) but you can find them all very easily via your mobile App Store and/or via a Google search. And they are all available via the NSA’s on-line gift shop (kidding).

First, Quincy’s suggestions:

1. Download “Signal”, or Start Using “WhatsApp” to send text messages.

Encryption is a fancy computer-person word for scrambling your data so no one can understand what it says without a key. But encrypting is more complex than just switching a couple of letters around. Larson said that by some estimates, with the default encryption scheme that Apple uses, “you’d have to have a supercomputer crunching day and night for years to be able to unlock a single computer.” He said the best way to destroy data was not to delete it, because it could potentially be resurrected from a hard drive, but to encode it in “a secure form of cryptography.”

Signal is one of the most popular apps for those who want to protect their text messages. It is free and extremely easy to use. And unlike Apple’s iMessage, which is also encrypted, the code it uses to operate is open source. You can be sure by looking at the code that they’re not doing anything weird with your data. In general, the idea behind the app is to make privacy and communication as simple as possible, said Moxie Marlinspike, the founder of Open Whisper Systems, the organization that developed Signal. That means that the app allows you to use emojis, send pictures and enter group texts.

One bit of friction: You do have to persuade your friends to join the service, too, if you want to text them. The app makes that easy to do.

WhatsApp, the popular chat tool, uses Signal’s software to encrypt its messaging. And in Facebook Messenger and Google’s texting app Allo, you can turn on an option that encrypts your messages.

Signal is available for both Android and iOS.

2. Protect your computer’s hard drive with “FileVault” or “BitLocker”.

Your phone may be the device that lives in your pocket, but Larson described the computer as the real gold mine for personal information. Even if your data were password protected, someone who gained access to your computer “would have access to all your files if they were unencrypted.” Luckily, both Apple and Windows offer means of automatic encryption that simply need to be turned on.

3. The way you handle your passwords is probably wrong and bad.

You know this by now. Changing your passwords frequently is one of the simplest things you can do to protect yourself from digital invasion. But making up new combinations all the time is irritating and inconvenient. Larson recommends password managers, which help store many passwords, with one master password. He said he uses LastPass but knows plenty of people who use 1Password and KeePass, and he doesn’t have a strong reason to recommend one over another.

So that means you may want to write them down in one secure location, perhaps a Post-it note at home. It seems more far-fetched that a hacker would bother to break into your home for a Post-it note than find a way into your computer. If you take that route, we suggest setting a weekly or biweekly calendar reminder to change your passwords.

As far as making passwords up goes: Don’t be precious about it. Use a random word (an object near you while you are hunched over your Post-it), scramble the letters and sprinkle in numbers and punctuation marks. If you’re writing passwords down, you don’t have to worry about making them memorable.

4. Protect your email and other accounts with two-factor authentication.

When you turn this step on, anyone trying to sign in to your email from new devices will have to go through a secondary layer of security: a code to enter the inbox that is sent to your phone via text message. (Though sadly, not through Signal.) You can also set two-factor authentication for social media accounts and other sites. But email is the most important account, since many sites use email for password recovery, a fact that hackers have exploited. Once they have access to your email, they can get access to banking, social media, data backups and work accounts.

5. Use a browser plug-in called “HTTPS Everywhere”.

Developed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital security organization, it ensures that you are using the secure form of websites, meaning that your connection to the site will be encrypted and that you will be protected from various forms of surveillance and hacking. And this is a good time to note that you should always find out whether the Wi-Fi network you are using is secure. Public networks — and even private networks without security keys — often are not.

6. Invest in a Virtual Private Network, or VPN.

Using a VPN will shield browsing information and hide your location. I can highlight three providers which we all use: Freedome by F-Secure, TunnelBear and a service called Private Internet Access.

7. Remember that incognito mode isn’t always private.

You may be in such a hurry to use this feature, available on Chrome, Safari and Firefox, among other browsers, that you do not heed its clear warning. On Chrome, the second paragraph of the “incognito” home screen spells it out for you. “You aren’t invisible,” it says. “Going incognito doesn’t hide your browsing from your employer, your internet service provider or the websites you visit.” We use Tor, a browser that allows for private web activity. But we’re not going to recommend that here, mostly because Tor is relatively slow and clunky at the moment. But what is interesting is other browsers are adding ways to browse more securely. Apple is very security conscious and one of my Apple contacts tells me they are looking at incorporating Tor-like features into Safari.

8. Do sensitive searches in “DuckDuckGo”.

It is an alternative search engine. Google is built on the hacker ethic, and they have put principle above profits … well, in some aspects. But I meet people all the time who are extremely skeptical of any large software organization, and I think that’s reasonable. There are trade-offs. Google’s search results are more useful and accurate than competitors’ precisely because of the ways it collects and analyzes information about its customers’ searches.

9. Cover your webcam with tape.

That way, if someone has found a way to compromise your computer, they cannot spy on you through its camera.

Now … on to David Koff and Bennet Madison. They make these opening points:

1. everything is hackable

2. cybersecurity is the practice of minimizing intrusions into our digital affairs

3. two basic truths:

(a) you can usually prevent most individuals from gaining access to your valuables with a bit of reasonable effort and expense

(b) but you usually can’t prevent those with the right tools and experience from bypassing even the most sophisticated alarm system

On to their suggestions (explanatory notes by David):

1. Don’t Open Emails from Strangers

Not now, not ever. I know, I know, that sounds extreme. I get it, but you won’t find any cybersecurity expert who’d advise you otherwise. Be tough! Look at the subject line, the sender’s name, and the sender’s email address, all of which should be visible before you open the email. If you don’t recognize the individual or organization, delete the email. Remember: If someone important is really trying to reach you, they probably already have your phone number. Let them call. And by the way, if you forget this rule, don’t panic: Opening an email won’t infect you with a virus. The real time bomb isn’t the email: It’s in the links and the attachments. Never click any links in the body of an email that comes from a stranger. And for all that’s holy, never view or download any attachments in an email that comes from a stranger. Those links and attachments are where the malicious code lurks, waiting for you to activate it.

2. Always Double-Check Email Addresses and Web Links

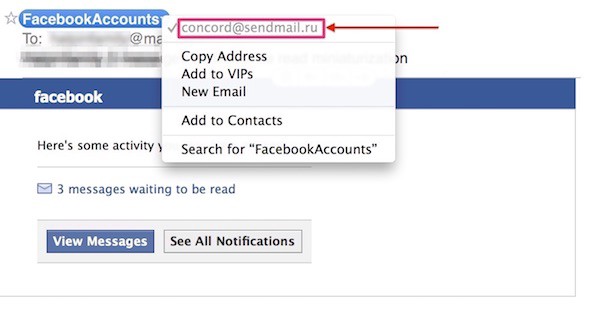

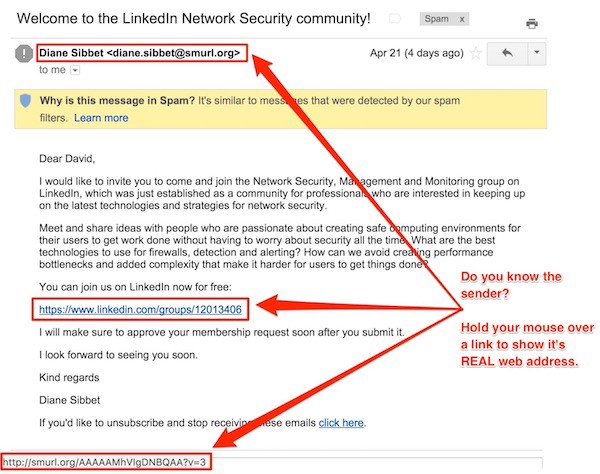

Sometimes, we think that we’re opening emails from people and organizations we already know. But are we? Hackers can effectively mimic other people and organizations. For example, even though I use Facebook and LinkedIn, the following emails sure aren’t from anyone at either of those companies.

The first email, upon closer examination, doesn’t come from facebook.com, but from sendmail.ru, an email address in Russia. Russia?! Thank you, but I’m Putin that in my spam folder. The second email not only features a name and a website that I don’t recognize, but it also reveals a poorly kept secret: When I hold my mouse over the link in the email, its actual destination (shown in the red box at bottom) doesn’t match the link address written in the email. Final analysis: spam.

Prevent being scammed by checking the email address and website links.

3. Update Your Operating System (aka OS)

Electronic devices, just like your car, require tune-ups. Tune-ups are accomplished by performing software updates to your operating system. Click on any of the following links to learn how to update software on a Mac, a PC, an iOS device, and an Android device. Schedule this. Literally put a reminder in your calendar, just like you do with your bills, to update the software on your computers, smartphones, and tablets. Then, make like Nike and just do it.

4. Update Any Third-Party Software

Third-party software is any software that isn’t your operating system. I’d focus on updating any Chrome, Firefox or Opera web browsers; Oracle’s Java software, and any free Adobe plug-in, including Flash, Reader, Shockwave, and AIR. Click on any of the underlined words to go directly to the maker’s update page for that software.

5. Download Software Only from the Makers of That Software

I wouldn’t buy a Subaru from a Ford dealership, and I wouldn’t download Adobe Reader from a site called TryMyFunDownload.com. Instead, I’d go to Adobe’s website and locate the specific download page for Adobe Reader. Never download software from a third-party website.

6. Delete Anything You No Longer Need from Your Computer, Smartphone, or Tablet

If you don’t keep every pair of underwear you’ve ever worn, then don’t keep every app, file, and document you’ve ever downloaded. Hackers can exploit old software to gain access to data. Perform a spring cleaning on your digital devices. On Macs, I use AppCleaner to fully remove software, including the buried bits and pieces. On Windows 10, there are two options for deleting applications demonstrated here; for older versions of Windows, here are the instructions. Follow these directions to delete iOS apps; and here’s how you delete Android apps. As for what to delete, I’d start by eliminating any apps that malicious actors — no, not James Woods — use to hack your computer. This includes Adobe’s Flash and Reader applications and Oracle’s Java.

7. Never Use Public or Kiosk Computers

These are frequent targets for hackers who install software and hardware to record your keystrokes. That means when you log into any website — email, banks, home or business servers — you risk your username and password being recorded. Use your own computer or none at all. Yes, that also means the computers you find in hotel lobbies. If the public can access the computer, then you should not.

8. Never Conduct Financial Transactions on a Wireless Network

This one is hard because I’m asking that you conduct banking and shopping only on a computer that is physically connected to the internet. Doing so makes stealing your information far more difficult for would-be hackers. “Hey, I’ll just use my cellphone,” you say. My response to that: Don’t. Cell networks are, sadly, also reliably insecure. Wait until you are at a location — either home or work — where you keep a computer physically connected to the internet via an ethernet cable. This might mean you’ll want to purchase and keep an ethernet cable at home for use with one of your home computers. Do it: For less than $2, you’ll be better protected. Famed hacker Kevin Mitnick has a different recommendation: Purchase a Chromebook for $200 and just use that device — in guest mode — for banking. If you haven’t heard of Kevin Mitnick, ask the FBI: He was on their most-wanted list for years. My advice is that spending $2 for an ethernet cable is a lot easier and gives you much (but not all) of the protection that Mitnick’s solution offers.

9. Never Connect Any Media (Writable CDs and DVDs, USB Sticks, SD Cards, External Hard Drives) Unless You Bought It New

Companies love to give away media with their logo. You’ve probably seen this at conventions, organizations, and companies. While everyone loves free gifts, I encourage you to pull a Nancy Reagan and “just say no.” Same with any media you find in a thrift store, on the street, or anywhere else. Adopt this motto: “If it ain’t brand new, it’s not for you.” Hackers can put malicious software onto these devices, and then, with a bit of “branding,” easily distribute it to unsuspecting folks who will connect the hacker directly to their computers, tablets, and smartphones. In March 2017, even IBM (IBM!) fell victim to this: The company shipped customers USB sticks that included malicious code that was meant to target computers in Russia and India.

10. Never Provide Information About Your Accounts, Computers, or Networks to Anyone Without First Verifying Their Identity

“Social engineering” is the process by which hackers gain valuable and personal information about you and/or your company’s network. It’s also the most common method of hacking. Let’s say you work for a Fortune 500 company. If hackers wanted to compromise that company’s systems, they might call or write to you, posing as technical support reps from either Apple or Microsoft. Without thinking, you might reveal that your company is using Windows and that it runs several on-premise servers. DON’T BE THAT PERSON. Instead, ask for names, phone numbers, and emails. Provide no information to anyone you don’t personally know. Then, do your homework and confirm that the person who called and the company they represent are both legit. If not, report those sons-o-bitches!

11. Invest in Secure Offsite Data Storage

“Offsite” means that a backup of your data will be kept outside your home or office at a secure location. Many reputable companies offer secure and unlimited backup over the internet for about $60 a year. I’d check out the following four: BackBlaze, Carbonite, CrashPlan, and SugarSync.

12. Set Up an Onsite Backup

“Onsite” means that a backup of your data will be kept in the same location as your computers. Keeping an onsite backup means purchasing and then connecting an external hard drive to your computer. Other World Computing has offered a great selection of external hard drives for more than two decades. Best of all, it even provides videos that explain how to use the equipment.

Once your external hard drive is connected, you’ll need software to perform your backups. On Macs, Apple’s 100 percent free and automated backup system is called Time Machine, which you can read about here.