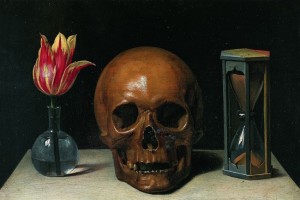

Still Life With A Skull (Philippe de Champaigne, 1660)

29 October 2016 – Death: it’s a fate that doesn’t discriminate, differentiate or favor. We are all going to die. Yet, for most of the time, we don’t really like talking about it, let alone like facing it. Could it be that we try to keep ourselves young, or we prefer youth over old age, because the latter reminds us of our mortality?

But why do animals grow old and die at characteristic ages? Even if maintained in peak condition and not eaten by your cat, your hamster is unlikely to make it much past its second birthday. And your cat might live for ten times that. Yet neither cat nor hamster will ever match the average healthy human for longevity.

In what seems to be a weekend of “all science, all the time” as I plow through a stack of Nature magazines I came across a study that uses demographic data to reveal a lifespan that human beings cannot exceed, simply by virtue of being human. It’s like running, as an accompanying News and Views article points out. Elite athletes might shave a few milliseconds off the world record for the 100-metre sprint, but they’ll never run the same distance in, say, five seconds, or two.

Human beings are simply not made that way. The same is true for longevity. The consequences of myriad factors related to our genetics, metabolism, reproduction and development, all shaped over millions of years of evolution, means that few humans will make it past their 120th birthdays. The name of Jeanne Calment, who died in 1997 at the age of 122, is likely to remain as long in the memory in the Methuselah stakes as that of Usain Bolt on the Olympic track.

Maximum lifespan is a bald measure of years accumulated. It is not the same as life expectancy, which is an actuarial measure of how long one is expected to live from birth, or indeed from any given age. Life expectancy at birth has increased in most countries over the past century, not because people have longer lifespans, but mainly because infectious disease does not kill as many infants as it once did. Factors such as poverty and warfare conspire to decrease life expectancy. Although life expectancy at birth has risen steadily for both men and women in France since 1900, for example, there are dramatic and poignant drops that coincide with the two world wars.

In article accompanying the study it is noted that in Britain in the early twentieth century, many children still died from infectious diseases, and men would die shortly after retiring from physically demanding jobs. The National Health Service was the political response. It has become, in some ways, the victim of its own success. People live longer than they did even a few decades ago, and die (eventually) of different (and more expensive) complaints. As any beginning medical student is soon taught, gerontology is far from a dying discipline. So if we owe our increases in life expectancy to better public health, nutrition, sanitation and vaccination, is it not fair to ask whether more-effective treatments for diseases such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s might also yield dividends in maximum lifespan? Will 120th birthday parties become routine, outmatched by a small yet increasing number of sesquicentenarians? The demographic data say no. People are living longer, and the population as a whole is greying, but the rate of increase in the number of centenarians is slowing, and might even have peaked.

Ah. But could it be possible, in some science-fictional future, to break free from the bonds of human life expectancy and increase lifespan indefinitely? Isn’t this what all that “artificial intelligence” blather is about? An unquenchable desire for eternal life has preoccupied humanity from the earliest times, as attested by the earliest passages of the Bible, the Gilgamesh epic and many other stories from our past. Perhaps the chilliest evocation of mortality comes in Bede’s seventh-century Ecclesiastical History of the English People, in which a chieftain remarks that the “few moments of comfort” offered by human life are as the brief flight of a sparrow through a warm and lighted mead hall, in through one door, and out through the other, back into a dark, storm-tossed and demon-haunted night of which we know nothing.

No wonder we’d all like a little more light.

Technological solutions might one day transcend the limitations of the human body, but transcend them they must — mere extension is already yielding diminishing returns. The risks of transcendence are twofold. First, it might be that to extend our lives beyond our normal span, we must somehow become other than human. After all, what would a 50-year-old hamster be like? The unintended consequences of immortality are graphically and grimly illustrated in Aldous Huxley’s 1939 novel After Many A Summer, in which people fed on a life-extending diet of carp intestines live for centuries — at the cost of turning into witless apes. Second, there is a risk that life wouldn’t really be that much longer — it would only feel like it.

I’ve become more philosophical about it all. What is it about death that makes us scared? Is it the “being dead” part, or the “dying part”? If it’s the being dead part then our fear is illogical says the ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus. He sets out the “no subject of harm” argument: death “is nothing to us”, because when we are alive, it has not come; and when we are dead, we cease to exist, as does our capacity to experience.

His basic argument as laid out is a valid one. The conclusion does follow if we accept the premises as true. We must accept the first premise based on Epicurus’ metaphysics of atomism and physicalism. Critics of Epicurus also seem to assume that his disregard of death implies an indifference to life. This can not be assumed, and it is in fact incorrect. Being alive must be generally considered to be a good. If as Epicurus says, that “pleasure is the first good and natural to us,” and we agree that we must be alive to experience pleasure, it follows that being alive is a good.

Yes, someone could object to this reasoning by offering the example of someone serving a life sentence of solitary confinement or someone with a painful, terminal illness. They might be inclined to say that in this case that being alive is not a good, and furthermore that death would be better. If death were indeed better then it would be a good, and thus would contradict our conclusion. I would counter by saying that although life as a whole may not be good for these people that it is still necessarily a good. There is always the possibility of release from confinement, or of a cure. Also, these people are still able to enjoy the pleasure of reading a good book or in the case of the terminally ill, to enjoy the pleasure of their loved ones. Further, to say that death is a good is but word play. Based upon our previous elucidation of “death,” one could say that dying or the moment of death might be a good for these persons because their pain would presumably be shortened. But being dead is still nothing to them; they can not experience it.

It’s most likely that what we fear is the pain or terror of dying. Yet, that is not the same as death. Another Epicurean argument is from the poet Lucretius:

“Look back at the eternity that passed before we were born, and mark how utterly it counts to us as nothing. This is a mirror that Nature holds up to us, in which we may see the time that shall be after we are dead.”

If we don’t find our inexistence before birth so bad, then why should we find our inexistence once we are dead so? Lucretius thinks they are exactly the same state.

Of course, as persuasive and logical as these arguments are, there is still the irrational part of us that finds them hard to swallow. What is the best way to deal with death? Oliver Burkeman in The Antidote suggests a middle way. He says that we shouldn’t deprive of ourselves of thinking that death is bad, because it is. Death means the cessation of being with loved ones, smelling the roses, savoring a delicious meal; essentially, of life. Death also signifies the end of hopes, dreams and what could have been. This is where we get to the crux of the argument: by remembering that we must die, we must make the most of what we have today. By living a more meaningful life, we ought to live with as little regret as possible.

In case we have trouble distinguishing between the small and big stuff, Burkeman suggests this exercise by the psychologist Russ Harris:

“Imagine you are 80 years old (or even older) and you are looking back on your life. Then, complete the sentences: “I wish I’d spent more time on…; I wish I’d spent less time on…”

In The Meaning of Things, the philosopher A.C. Grayling writes about death as being the resurgence of a new cycle. He writes that “nothing seems so dead as clematis in winter”. Yet, once spring arrives, its green fingers start to sprout. Nature has a way of sorting itself out. This is a comforting way to look at death: that it’s part and parcel of nature’s cycle. “All are from dust, and to dust all return,” notes the book of Ecclesiastes. I am irreligious but agree with the statement.

Of course, another comfort is to believe in the afterlife. The Pulitzer Prize winner The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker states that we think of ourselves as immortal ‘heroes’, that religion (and thus the afterlife), art, charity, institutions as well as wars and conflict all symbolize our desire to live on, even when the physical dies. Becker remarks that these “immortality projects” may have built great civilizations, but they’ve destroyed them too.

In the philosopher Alain de Botton’s vlog, How we will die he gives three pieces of advice to take to heart: be kind to those around us and to ourselves; understand our true talents and potential and put them to use; and appreciate every day, “…aware that the end might not be so far away.”

It is now dawn. The sun starts to rise over the harbor; its rays are making me squint. In the moment, I’m thankful for another beautiful day.