Für deutsche Version klicken Sie hier

για την Ελληνική έκδοση κάντε κλικ εδώ

I am an opsimath at heart and I think everything is related. I attend a cornucopia of conferences and events (click here) in Barcelona, Spain; Brussels, Belgium; Cannes, France; Geneva, Switzerland; Lille, France; London, England; Munich, Germany; Paris, France; and Perugia, Italy. They provide me perspective, a holistic education. I call it my personal “Theory of Everything”.

This series will reflect the many things I write a write about, glimpses of a broader picture I’m looking into.

It will also become a video series.

12 August 2016 (Milos, Greece) – Like everyone else, I presume, I feel an attraction for zero points, for the axes and points of reference from which the positions and distances of any object in the universe can be determined:

- the Equator

- the Greenwich Meridian

- sea-level

There used to be a circle on the large square in front of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris (it disappeared, alas, when they were making the carpark and no one thought to put it back) from which all French distances by road were calculated. You could even calculate other points across the globe.

And we all like to measure where we are vis-a-vis human history. Christian Tomsen, a coin collector largely untrained in archaeology, started us off in the early 1800s when he divided a broad swathe of human history into stone, iron, and bronze ages. Oh, yes. The objections started soon afterward. For one thing, the archaeological record doesn’t divide itself as cleanly along material lines as Thomsen had imagined. For another, some argued the classifications were better suited for Europe than the rest of the world where they made no sense.

Yet they persist, both in academia and in the public imagination, in part because they carry an important insight: materials are transformational. Cheap iron cutting tools, for example, allowed people to deforest and inhabit fertile land, dramatically expanding populations as well as the production of iron. As they age, civilizations make materials. And materials make civilizations.

I think of it today along the lines of technology history, ages also seen as “before-and-after” something. My world consists of three ecosystems or networks, somewhat distinct but also converging. Or maybe becoming more “entangled” to borrow a theme from Neri Oxman:

▪ In my mobile/telecommunications world we measure things “Before the iPhone/After the iPhone”

▪ In my e-discovery/litigation technology world we measure things “Before Peck/After Peck”

▪ In my neuroscience world we measure things “Before the functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner/After the fMRI”.

So let’s set the stage …

With the onslaught of artificial intelligence (AI) we seem to have launched into a state where we assume that intelligence is somehow the teleological endpoint of evolution – incredibly anthropocentric, and pretty much wrong along every conceivable axis. Intelligence is an evolutionary response to a particular context and set of survival challenges. There’s no objective reason it should be more prized than flight, speed, fertility, or resilience to radiation.

But it fits so neatly into the hot topic of the day … whether we are in a “new age”, called the Anthropocene – where the human imprint on the global environment and human life has now become so large and active that it rivals all the great forces of Nature in its impact on the functioning of the Earth system and human development.

The breathtaking advance of scientific discovery and technology has the unknown on the run. Not so long ago, the Creation was 8,000 years old and Heaven hovered a few thousand miles above our heads. Now Earth is 4.5 billion years old and the observable Universe spans 92 billion light years.

And as we are hurled headlong into the frenetic pace of all this AI development we suffer from illusions of understanding, a false sense of comprehension, failing to see the looming chasm between what your brain knows and what your mind is capable of accessing.

It’s a problem, of course. Science has spawned a proliferation of technology that has dramatically infiltrated all aspects of modern life. In many ways the world is becoming so dynamic and complex that technological capabilities are overwhelming human capabilities to optimally interact with and leverage those technologies.

And we are becoming aware of the complexity. Slowly. As Melanie Mitchell puts it in her indispensable book Complexity: A Guided Tour, we are into complex systems (weather patterns, markets, text analysis, population analysis, brain scanning, you name it) that turn out to be extremely sensitive to tiny variations in initial conditions, which we call, for lack of a better term, chaos.

And if what you know of chaos science is limited to the published works of Dr. Ian Malcolm, you’ll despair to learn that the reality of it is a lot less sexy and a lot more mathy than it is in Jurassic Park:

I am not adverse to technology. But I am cautious. I keep my “detector” hat on at all times. I belong to the Church of Techticism, Al Sacco’s brilliant new mash-up that is “an odd and difficult to pronounce term derived from a combination of the words “skepticism” and “technicism,” meant to convey a general sense of distrust toward the mainstream technology world and its PR hype machine”.

I see it in my three personal “ages” described above … mobile, e-discovery, neuroscience … which have not, and will not, moved in a forward, lineal fashion:

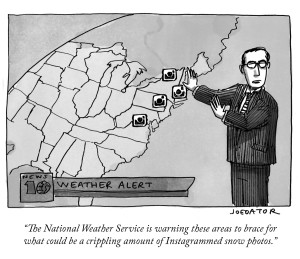

▪ In mobile, the Amazon Echo and Google Home have slapped Apple in the face. What happens when there is no “device”? What happens to that advantage and ability to command a premium, when there isn’t a product to hold, when appearance, materials, “look and feel” has suddenly vanished. The shift to systems which don’t need us to look at them directly and which feed information back to us by means other than an integrated item with a screen, doesn’t so much move the goalposts as set fire to them and terraform the field where they were standing. Granted, our obsession with photographs and cameras has forestalled that shift; Instagram and Snapchat demonstrate that, when it comes to social interaction, we love the visual. That suggests screens and devices – in other words, things we actually hold and carry around – remain important. In this series I will devote a full chapter to these issues.

▪ A short time ago a new philosophy emerged in the e-discovery industry which was to view e-discovery as a science — leading to the emergence of new intelligent technology — predictive coding. It’s advancement is due, in my believe, solely to Judge Andrew Peck and his measured countenance (hence “Before Peck/After Peck”). But what happens when it fails? Last year we had a noteable fail in predictive coding: 85% false positives, thousands of documents the predictive coding software could not code, “state-of-art” software reading photographs as Excel spreadsheets and trying to convert them, a move to brute force review, etc. To be fair, it was due to the complexity of the data and the poor execution of the technology by the neophytes involved. As one predictive coding expert briefed on the case noted “even the steam engine blew up several times before we got it right”. Fair enough. The technology and the process will get better. Predictive coding will advance because of the collision of two simple, major trends: (1) the economics of traditional, linear review have become unsustainable while (2) the early returns from those employing predictive coding are striking. But in a world that now expects instant gratification it is no wonder one of the law partners involved exclaimed “when this stuff becomes push-button and even I can do it, then call me”. I will expand on these issues in a later chapter.

▪ Modern neuroscience would be impossible without functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. In brief, fMRI is a specialized form of MRI, an imaging technique that enables you to look inside the body without having to cut it open.The technique is barely 25 years old, but thousands of studies that use it are published each year. The headlines are screaming it. Last month a new map of the brain based on fMRI scans was greeted as a “scientific breakthrough.” But now a series of studies have found deep flaws in how researchers have been using fMRI. It relates to how the fMRI finds and interprets “standard activity”. The trouble is, what is “standard” activity can vary from one object to another, or even from person to person. So these AI software packages and statistical tests have to make a lot of assumptions, and sometimes use shortcuts, in separating real activity from background noise. Because of this scientists expect a 5% rate of false positives, but this series of studies found it is much, much higher. This will be a difficult chapter but I shall draw upon my neuroscience program at Cambridge University to walk you through it.

The AI “spring” …. let’s try this again

Artificial intelligence started as a field of serious study in the mid-1950s. At the time, investigators expected to emulate human intelligence within the span of an academic career. But hopes were dashed when it became clear that the algorithms and computing power of that period were simply not up to the task. Some skeptics even wrote off the endeavor as pure hubris.

So after decades of disappointment, artificial intelligence is finally catching up to its early promise, thanks to a powerful technique called deep learning. We’ll discuss that a lot in this series.

During my AI program at ETH Zurich I learned that people call the 1980s and the present the two “Al springs”, during which expert system models and now deep learning algorithms respectively stirred up a frenzy in Al excitement, funding, startups, talent wars, media attentions and much more. I’d call these the “Al summers”, not springs. The “Al springs” are the periods that proceeded these two “summers”, which was the 1990s and early 21st century for this latest Al frenzy. During these spring times, I was told, “all flowers blossomed”.

Academia enjoyed a relatively quiet yet extremely productive era of many different ideas and models. I learned about the most fundamental theories and important prototypes in image segmentation, object recognition, scene understanding, 3D reconstruction, optimization, graphical models, SVM, neural network, inference algorithms, open-source datasets, benchmarking challenges and much more. They became the seeding technology for today’s deep learning, AR, VR, self-driving cars, etc. Understanding that development has helped me understand how we got to today.

Let’s conclude this tl;dr first installment on a philosophical note

“Greg likes to be philosophical”

For artificial intelligence, nightmare scenarios are in vogue. We are told of the impending march of “The Terminator”, a creature from our primordial nightmares: tall, strong, aggressive, and nearly indestructible. We’re strongly primed to fear such a being – it resembles the lions, tigers, and bears that our ancestors so feared when they wandered alone on the savanna and tundra. We are told they will become our unaccountable overlords, reaping destruction.

I would posit that if you pick up the newspaper of scan your news feed the daily news reveals the suffering that tends to result from powerful, unaccountable humans so I think we have that covered pretty well, thank you.

Our problem when we “think about machines that think” is that our feeling, emotion, and intellectual comprehension are inexorably intertwined with how we think. Not only are we aware of being aware, but also our ability to think enables us at will to remember a past and to imagine a future. Machines are not organisms and no matter how complex and sophisticated they become, they will not evolve by natural selection as we did.

And that’s the point, isn’t it? By whatever means machines are designed and programmed, their possessing the ability to have feelings and emotions would be counter-productive to what will make them most valuable. They are not bound by the irrationalities that hamstring our minds.

But our judgment about whether this poses a utopian or dystopian future will be based upon thinking, which will be biased as always, since it will remain a product of analytical reasoning, colored by our feelings and emotions.

And as far as the end of humans …. some perspective, please. Yes, I know. Human life is a staggeringly strange thing. Here we are, on the surface of a ball of rock falling around a nuclear fireball called the Sun, and in the blackness of a vacuum the laws of nature have conspired to create a naked ape that can look up at the stars and wonder “Where in hell did I come from?!” Particles of dust in an infinite arena, present for an instant in eternity. Clumps of atoms in a universe with more galaxies than people.

But, alas, there are chemical and metabolic limits to the size and processing power of “wet” organic brains. Maybe we’re close to these already. But no such limits constrain silicon-based computers (still less, perhaps, quantum computers): for these, the potential for further development could be as dramatic as the evolution from monocellular organisms to humans.

So, by any definition of “thinking,” the amount and intensity that’s done by organic human-type brains will be utterly swamped by the cerebrations of AI. Moreover, the Earth’s biosphere in which organic life has symbiotically evolved, is not a constraint for advanced AI. Indeed it is far from optimal—interplanetary and interstellar space will be the preferred arena where robotic fabricators will have the grandest scope for construction, and where non-biological “brains” may develop insights as far beyond our imaginings as string theory is for a mouse.

As Martin Rees (former President, The Royal Society; Emeritus Professor of Cosmology & Astrophysics, University of Cambridge) puts it:

“Abstract thinking by biological brains has underpinned the emergence of all culture and science. But this activity—spanning tens of millennia at most—will be a brief precursor to the more powerful intellects of the inorganic post-human era. Moreover, evolution on other worlds orbiting stars older than the Sun could have had a head start. If so, then aliens are likely to have long ago transitioned beyond the organic stage.

So it won’t be the minds of humans, but those of machines, that will most fully understand the world—and it will be the actions of autonomous machines that will most drastically change the world, and perhaps what lies beyond.”

So, you might ask, what’s in store in this series? A brief synopsis of some coming chapters:

Personal machine learning

It is a flawed assumption that communal machine learning is the only value proposition for the development of AI. There is a personal side and I think Amazon Echo and Google Home are the primitive presursors. It is about “training”. Everyone doing machine learning has to train their network. There are massive data sets that form the basis of large communal deep learning initiatives and they are the basis of how a network is trained.

Personal machine learning is now just happening, in the same sense that large data sets train a network based on communal trends and data. There is a battle looming for the “personal life assistant” consumers will hire to help them at an individual level and be smart and predictive for things unique to their lives.

How filtering algorithms work and alter our world view

Public discourse is increasingly mediated by proprietary software systems owned by a handful of major corporations. Google, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube claim billions of active users for their social media platforms, which automatically run filtering algorithms to determine what information is displayed to those users on their feeds. A feed is typically organized as an ordered list of items. Filtering algorithms select which items to include and how to order them. Far from being neutral or objective, these algorithms are powerful intermediaries that prioritize certain voices over others. An algorithm that controls what information rises to the top and what gets suppressed is a kind of gatekeeper that manages the flow of data according to whatever values are written into its code.

In the vast majority of cases, platforms do not inform users about the filtering logics they employ—still less offer them control over those filters. In what follows, we will describe how filtering algorithms work on the leading social media platforms, before going on to explain why those platforms have adopted particular filtering logics, and how those logics structure a political economy of information control based primarily on advertising and selling consumer products.

Our heightened visual culture and the proliferation of algorithmic techniques

In 2015, humanity put 2 or 3 trillion photographs on the internet (sources: Google, Facebook, Magnum Photos). Our faces, our streets, our friends – all online. Now, researchers are tapping into this vein of information, studying photos in bulk to give us fresh insights into our lives and our cities. For example, a project called AirTick uses these photos to get a handle on air pollution. The AirTick app estimates air quality by analyzing photos of city streets en masse. The app examines photos from large social sharing sites, checking when and where each was taken and how the camera was oriented. It then matches photos with official air quality data. A machine learning algorithm uses the data to work out how to estimate the level of pollutants in the air based solely on how it appears in photographs.

Or such image technology as Honeywell’s Portable Image Recognition and Analysis Transducer Equipment, or PIRATE, which is designed to be taken into potentially hazardous areas and report on the conditions. It can be placed remotely and report data back to a central location before human enter – again, a machine learning algorithm using data to work out the dangers.

Or Google’s advanced Cloud Vision API for text analysis which has an OCR (optical character recognition) feature that can see the text within an image (it supports multiple languages) so you can pull out the text for easier access and analysis.

Or better yet, 3-D mapping in phones. Last year I was allowed into the R&D space at Qualcomm to see a prototype a 3-D mapping software for mobile phones. It has the ability to literally scan a scene with your phone’s camera and have the images automatically stitch themselves together in three dimensions. In the future, witnesses at a major event (a police shooting perhaps?) will be able to document it with their mobile phones in a way that will allow others to step inside the scene—giving people an instantaneous understanding of the event that no video or photograph could provide.

Nicholas Mirzoeff in his book “How To See the World” notes that our heightened visual culture coupled with the proliferation of algorithmic techniques for image analysis will lead us to “machine-learn meaning”. I’m going to jump into a laundry-list of many of these competencies.

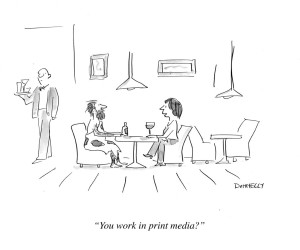

Data journalism

Every year I attend (or my team attends) the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy. It is where I have learned to get people’s attention amongst the cacophony of information out there. How to determine when content needs to be a comprehensive take, or a ” quick snap”. And how to tell a story with data, how to create a narrative.

And over the last few years a lot of sessions on AI technology used to publish storis: automated financial stories about standard corporate earnings (the Associated Press says the technology has allowed it to publish 3,700 additional stories each quarter) and more sophisticated software like “Emma”. In a recent journalist-versus-machine contest, “Emma” and her challenger were each primed to write about the official UK employment data. “Emma” was indeed quick: she filed in 12 minutes to the “human journalist” time of 35 minutes. And her copy was also better than expected. And she even included relevant context such as the possibility of Brexit – missed by the human.

A fascinating story. I’ll even tell you how I convinced one “robot” to tell me all he knew about pizza.

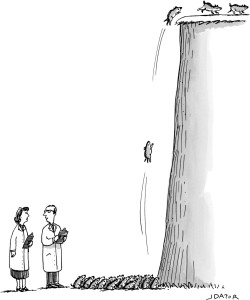

Gene-editing systems

“We crossed lemmings with salmon”

I will have a piece on “the age of the red pen” – CRISPR and other gene-editing systems, all the product of genetic algorithms developed under very powerful AI. The power of CRISPR and other such technologies promises to alter our future in unpredictable ways. We will become the masters of our own evolution, determining what kinds of changes to our form and function we will incorporate into our children.

Mathematized governance

I would be remiss not to address AI and its impact on law and regulation. Not IBM’s ROSS and the other applications common in the legal media. But the AI information processing systems already being performed by computers in the regulation and control of society: mathematized governance. They are being used in criminal justice in areas like parole and probation, bail, or sentencing decisions. And in areas like housing and treatment decisions, identifying people who can safely be sent to a minimum security prison or a halfway house, and those who would benefit from a particular type of psychological care.

It is the lurking danger in so many other areas: technocrats and managers cloak contestable value judgments in the garb of “science” and satisfy a seemingly insatiable demand these days for mathematical models to reframe everything. The worth of a worker, a prisoner, a service, an article, a product … whatever … is the inevitable dictate of salient, measurable data.

AI technology and the explosion of surveillance capabilities

“Oh, are you attacking from home today?”

Since history began to be recorded, political units—whether described as states or not-—had at their disposal war as the ultimate recourse. Yet the technology that made war possible also limited its scope. The most powerful and well-equipped states could only project force over limited distances, in certain quantities, and against so many targets. Ambitious leaders were constrained, both by convention and by the state of communications technology. Radical courses of action were inhibited by the pace at which they unfolded.

And for most of history, technological change unfolded over decades and centuries of incremental advances that refined and combined existing technologies.

What is new in the present era is the rate of change of computing power and the expansion of information technology into every sphere of existence. In his last book “World Order” Henry Kissinger noted:

“The revolution in computing is the first to bring so many individuals and processes into the same medium of communication and to translate and track their actions in a single technological language. Cyberspace-——a word coined, at that point as an essentially hypothetical concept, only in the 198Os——-has colonized physical space and, at least in major urban centers, is beginning to merge with it. Communication across it, and between its exponentially proliferating nodes, is near instantaneous. Equilibrium has vanished. “

The forces of technology are ushering in a new age of openness that would have been unthinkable just a few decades ago. Governments, journalists, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) can now harness a flood of open-source information, drawn from commercial surveillance satellites, drones, smartphones, and computers, to reveal hidden activities in contested areas—from Ukraine to Syria to the South China Sea. In the coming years, diplomacy will continue to play its part in encouraging states to be open about their activities, but true breakthroughs will come from Silicon Valley rather than Geneva.

I’m going to touch upon the rapid advances in AI technology that have fueled an explosion of surveillance capabilities: commercial surveillance satellites, unmanned aerial vehicles, social media analytics, biometric technologies, and cyber defenses.

Speech recognition: the holy grail of artificial intelligence

“You call that nudity, strong language and scenes of a sexual nature!”

This will be my most fun chapter because it will blend my AI studies at ETH Zurich, and my neuroscience studies at Cambridge. Language, to me, is a powerful piece of social technology. It conveys your thoughts as coded puffs of air or dozens of drawn symbols, to be decoded by someone else. It can move information about the past, present and future, formalize ideas, trigger action, persuade, cajole and deceive. And language is inherently symbolic – sounds stand for words that stand for real objects and actions.

Language is a specifically human mental function, although some neurobiological adaptations associated with communication can be found in other primates, in other mammalian orders, and even in other kinds of animals. Exposure to language is necessary for its acquisition (culture), there are specific alleles of some genes for human language, and the brain circuits for language are mainly lateralized towards the left hemisphere (brain lateralization which I will address in detail).

And it can drive you nuts. In this election year in the U.S. (which feels more like a decade) we are trapped by people with the IQ of an aspidistra, the mindless chatter, like the music in elevators, spews machine-made news that comes and goes on a reassuringly familiar loop, the same footage, the same spokespeople, the same commentaries; what was said last week certain to be said this week, next week, and then again six weeks from now, the sequence returning as surely as the sun, demanding little else from the would-be citizen except devout observance. Albert Camus in the 1950s already had remanded the predicament to an aphorism: “A single sentence will suffice for modern man: he fornicated and read the papers.”

I speak three languages … English, French and Greek … and it a constant wonder when I discover the differences and their impact. For instance, Greek has two words for blue — ghalazio for light blue and ble for a darker shade. A study found that Greek speakers could discriminate shades of blue faster and better than native English speakers. Alexandra Dumont runs my Paris office and is a native French-speaker who grew up believing all squirrels were male. The French word for squirrel, écureuil, is masculine. Studies of French and Spanish speakers, whose languages attribute genders to objects, suggest they associate those objects with masculine or feminine properties.

Histoire in French means both “history” and “story,” in a way that “history” in English doesn’t quite, so that the relation between history and story may be more elegantly available in French. But no one has trouble in English with the notion that histories are narratives we make up as much as chronicles we discern.

And in my e-discovery world I have been Beta-testing a new linguistic software (let’s call it “Syntax”; I changed the name in keeping with my nondisclosure agreement). Think of it as Mindseye or Brainspace on speed. I used in an internal financial fraud investigation, and also an anti-trust investigation. It can detect uncharacteristic changes in tone and language in electronic conversations and can also be tailored for particular types of employees, in the first case those being traders.

Speech recognition has long been the holy grail of artificial intelligence research. Progress in speech recognition would stand for progress in AI more generally. And so it became a benchmark and a prize.

ENJOY YOUR SUMMER!

5 Replies to “REFLECTIONS ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND ECOSYSTEMS: Part 1 – the onslaught”