8 July 2016 – For most of us in the information management trade, data mining is a nifty tool. It is an interdisciplinary subfield of computer science. It is the computational process of discovering patterns in large data sets involving methods at the intersection of artificial intelligence, machine learning, statistics, and database systems. The overall goal of the data mining process is to extract information from a data set and transform it into an understandable structure for further use. Aside from the raw analysis step, it involves database and data management aspects, data pre-processing, model and inference considerations, “interestingness” metrics, complexity considerations. Data mining … as succinctly put by Prof Diego Kuonen … is “the analysis step of the knowledge discovery in databases process”.

The term is also a misnomer, because the goal is the extraction of patterns and knowledge from large amounts of data, not the extraction (mining) of data itself. And it has turned into a buzzword and is frequently applied to any form of large-scale data or information processing (collection, extraction, warehousing, analysis, and statistics) as well as any application of computer decision support system, including artificial intelligence, machine learning, and business intelligence. And while the term “data mining” itself has no ethical implications, it is often associated with the mining of information in relation to peoples’ behavior (ethical and otherwise).

But I am always intrigued by its various applications. In my monthly review of the arXiv (pronounced “archive”) database … a repository of electronic scientific papers in the fields of mathematics, physics, astronomy, computer science, quantitative biology, statistics, and quantitative finance … I found this research from the University of Vermont in the U.S. which examined the “emotional arcs” in Western literature. It’s what they call a study of our culture’s evolution through its texts using a “big data” lens. The opening paragraph of the research report:

The power of stories to transfer information and define our own existence has been shown time and again. We are fundamentally driven to find and tell stories, likened to Pan Narrans or Homo Narrativus. Stories are encoded in art, language, and even in the mathematics of physics: We use equations to represent both simple and complicated functions that describe our observations of the real world. In science, we formalize the ideas that best fit our experience with principles such as Occam’s Razor: The simplest story is the one we should trust. We also tend to prefer stories that fit into the molds which are familiar, and reject narratives that do not align with our experience.

Almost the entirety of Western literature can be fit neatly into just six story arcs, according to a new data-mining study. From the panoply of novels that Western society has produced, distinct narrative patterns emerge, and many attempts have been made to pin down the shape of a story and categorize a protagonist’s journey. French writer Georges Polti claims there are 36 different type dramatic stories, while others have counted seven narrative arcs or 20.

But new research from the University utilizing data-mining techniques suggests that the majority of the Western canon falls into one of six basic categories.

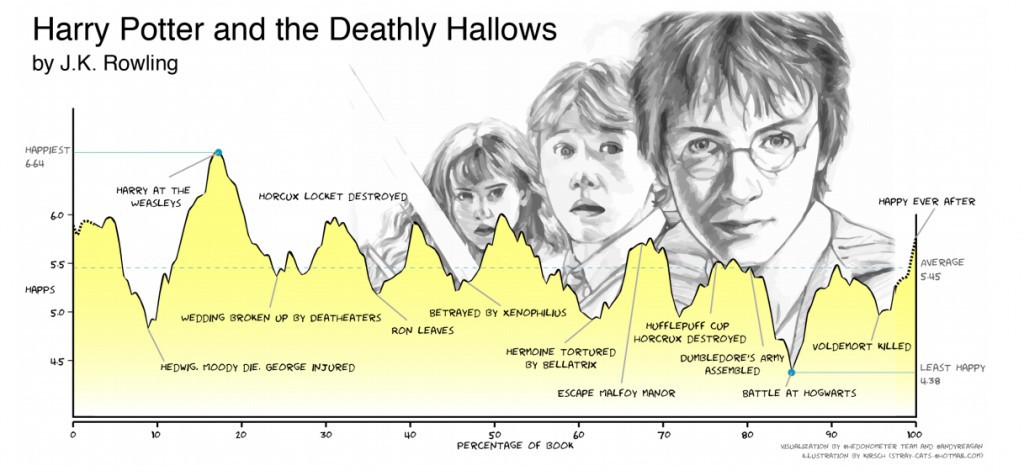

Researchers from the Computational Story Lab looked at over 1,700 books from Project Gutenberg for their study, winnowing out books such as dictionaries or those with less than 150 downloads. They analyzed the content of each book by taking samples of text, what they called “windows”, from throughout the story. They used the aptly named “hedonometer” , also developed by the Computational Story Lab, to compile a list of over 10,000 words and rate them on a spectrum of positive to negative using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service. They published their results last month on arXiv.org.

Adding up these windows over the course of a whole book produced graphs of characters’ fortunes — the highs and lows — throughout a given novel, and generated a broad visualization of the arc the story takes. According to the researchers, theses are the six story arcs that appear time and time again in Western literature:

“Rags to riches” (the story gets better over time);

“Man in a hole” (fortunes fall, but the protagonist bounces back);

“Cinderella” (there’s an initial rise in good fortunes, followed by a setback, but a happy ending)

“Tragedy” or “riches to rags” (things only get worse);

“Oedipus” (bad luck, followed by promise, ending in a final fall)

“Icarus” (opens with good fortunes, but doomed to fail)

While some stories don’t fit into these archetypes, the researchers say that the majority of Western classics fall into one of these categories. The “man in a hole” and rags-to-riches storylines seemed to be the most prevalent, depending on which statistical technique they applied to the data.

The researchers do note that their technique will only track broad changes in emotional valence over time, ignoring shifts that occur on the level of the sentence or paragraph. For example, they provide a detailed breakdown of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, which doesn’t fit neatly into any one of the categories:

However, the seven-book series, when taken as a whole, produces a more definite “rags to riches” story that fits in with established arcs.

In addition, their process cannot separate the fortunes of multiple characters, which could be a problem for books with multiple story lines — their program would definitely struggle with something as complex as Game of Thrones. Instead, their algorithm lumps the characters into one and tracks the overall emotional tone of the book from beginning to end.

How We Talk About Ourselves

The Gutenberg Collection is a compendium of classic works, however, more modern stories were not sampled. To call back to Game of Thrones again, there are many modern novels that tell more complex tales and which embrace emotional ambiguity, muddying the story’s arc and making a precise definition difficult.

In addition, the researchers looked only at works from the Western canon — analyzing stories from other cultures may produce very different trends and hint at diverse preferences. They say that they hope to include novels from other countries in future studies.

While their work hints at some of the broader patterns of thought that dominate Western culture, the researchers say that it could also help to teach computers how to communicate better. Teaching artificial intelligence to construct stories that follow popular arcs could allow them to form better arguments and relate concepts with more accuracy. The AI authors out there, even those trained on Shakespeare, fall somewhat short of engaging — or even comprehensible. Reading the stories that emerge from a particular culture gives unique insights into norms, practices and overall patterns of thought. If we want to teach computers to think like us, they’ll need to understand how we see the world.