24 January 2016 – Photography has been part of my life since my mother bought me a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye camera in 1961. I was 10 years old but even then I … maybe … saw its potential power. In a note I had written to my mother I said “I can take a picture of my entire life!”

A great photograph can explode the totality of our world, such that we never see it quite the same again. After all, as Kierkegaard also wrote, “the truth is a snare: you cannot have it, without being caught.”

Today photography has become a global cacophony of freeze-frames. Millions of pictures are uploaded every minute. Correspondingly, everyone is a subject, and knows it — any day now we will be adding the unguarded moment to the endangered species list. It’s on this hyper-egalitarian, quasi-Orwellian, all-too-camera-ready “terra infirma” that many photographers continue to stand out. Why they do so is only partly explained by the innately personal choices (which lens for which lighting for which moment) that help define a photographer’s style. Instead, the very best of their images remind us that a photograph has the power to do infinitely more than document. It can transport us to unseen worlds.

I live in Paris and I am a member of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie. It is a frequent stop. Paris is always awash with photography exhibits. As is London, a short train ride away. A few weeks ago I was in London to catch the two fabulous tandem exhibits on Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the most influential and pioneering of all photographers who developed an intimacy and vibrancy and that blended an unorthodox technique, a deeply spiritual sensibility and aesthetic that influenced almost every great photographer since.

Last year Paris Magnum – the world renown photographer agency … ran an enormous exhibit of the capital through the eyes of the greatest photographers. One comment heard throughout the exhibit was “where do we find today’s photographers that exhibit this same lyrical quality?”

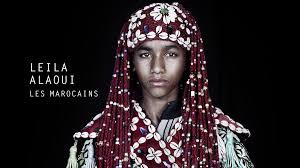

There was at least one: Leila Alaoui. She was a French-Moroccan photographer whose hauntingly beautiful photographs explored themes of migration, cultural identity and displacement. She died last week from injuries sustained during a terrorist attack in Burkina Faso. She was only 33. Leila had been on assignment in Burkina Faso for Amnesty International for less than a week, working on a series of photographs focused on women’s rights.

Her work has been displayed around the world … New York, Argentina, the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland … and her photos have also appeared in The New York Times and Vogue. She had a recent exhibit at the Maison Européenne and was described as one of the most promising photographers of her generation by Jean-Luc Monterosso, director of the Maison. He said “there was an internal light that illuminated both her and her work”.

Jack Lang, a former French minister of culture who is now president of the Institut du Monde Arabe, hailed Leila as a champion of the downtrodden and the dispossessed. In a France 24 interview he said “she was fighting to give life to those forgotten by society, to homeless people, to migrants, deploying one weapon: photography”. Samira Daoud, Amnesty International’s deputy regional director for west and central Africa, said Amnesty had chosen Leila to create portraits in Burkina Faso because of her ability to make “faces talk” without turning her subjects into victims.

The Maison Européenne provided me a brief bio:

Leila was born in Paris in 1982 and grew up in Marrakesh. She studied photography at the City University of New York before spending time in Morocco, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates. She had been living in Marrakesh and Beirut, Lebanon and a series of hers titled “The Moroccans,” part of a celebration of photographs from the Arab world, which featured characteristically intimate portraits of men and women in traditional outfits from different ethnic groups and from remote parts of the country, was met with huge reviews.

My take on her work was that she had been determined to avoid the exoticism that sometimes infected postcolonial portrayals of Morocco and the Arab world. She said she was influenced by the American photographer Robert Frank, who traveled across the United States in the 1950s recording life there with unsparing honesty.

Aida Alami, a journalist who often writes for Foreign Policy magazine and other magazines on Middle East subjects (whose work I have cited in my essay on last November’s Paris atrocities) was a childhood friend of hers and said Leila was fearless. From a piece in the New York Times:

“I saw Leila before she left for Burkina Faso, and she said, ‘Don’t worry, I have been to more dangerous places’. She was so optimistic, she thought that nothing bad could ever happen to her.. Once on assignment in Rabat a few years ago, I told Leila I wanted to interview some migrants. Leila, who was chronicling the plight of sub-Saharan immigrants there, invited me to come join her to meet some. Arriving at her home, I was surrounded by 40 migrants. She was cooking them dinner”.

I never met Leila but her fearlessness I can identity with. When I travel the Middle East, away from home and finding myself serving as unwelcome ambassador in countries hostile to the West, you must be fearless. I can only imagine that what propelled Leila was a ferocious determination to tell a story through transcendent images, to overcome what encumbered her quest in what must have been a daily litany of obstruction.

Every culture has its preferred description of the human distinction. In our culture, the preferred descriptions have included: the soul, the nous (and other appellations for the mind), the self, the ego, the person. In our time, the preferred description is: identity. In America, but not only in America, we are choking on identity. And not only on the identity of others; we are choking also on the identity of our own.

In his last essay, in 1938, the French sociologist Marcel Mauss observed: “It is plain that there has never existed a human being who has not been aware, not only of his body, but also at the same time of his individuality, both spiritual and physical.” Leila’s photos captured that individuality. She once said she never posed her models. She simply set up her studio outside, during market days. The people passed by, and those who wanted stopped to have their photo taken: “The only thing I asked of them was to face me”.

Leila’s photos are wonderful. And what is not visible but felt is her sense of responsibility toward those who dared to trust the stranger by opening the door to their quiet world. It’s a far riskier and time-consuming proposition to forgo the manipulated shot and instead view photography as a collaborative venture between two souls on either side of the lens.

Leila, we are blessed. Thank you.