America: a people with no shared narrative or history will find it very hard to keep a lid on disorder and violence.

And in its politics, nihilism reigns supreme.

27 January 2021 (Chania, Crete) – I think “America” is a land that never existed, will never exist. I think the default condition of humankind is not to thrive in broadly egalitarian and stable democratic arrangements that get unsettled only when something happens to unsettle them. The default condition of humankind, traced across thousands of years of history, is some sort of autocracy.

America itself has never had a particularly settled commitment to democratic, rational government. I’ve read so much American history these last 10 years, especially the last 4 years. I have bathed myself in the books of Kurt Anderson, Eric Foner, Lewis Lapham, George Packer, Alan Taylor and Daniel Vickers. Plus lots of “TL;DR” articles, too. Adam Gopnik had a long piece in The New Yorker last year:

“At a high point of national prosperity, long before manufacturing fell away or economic anxiety gripped the Middle West – in an era when “silos” referred only to grain or missiles and information came from three sober networks, and when fewer flew over flyover country – a similar set of paranoid beliefs filled American minds and came perilously close to taking power. Read Richard Rovere’s 1965 collection “The Goldwater Caper,” and you’ll read his history of a sizable group of people who believed things as fully fantastical as the Trumpite belief in voting machines rerouted by dead Venezuelan socialists. The intellectual forces behind Goldwater’s sudden rise thought that Eisenhower and J.F.K. were agents, wittingly or otherwise, of the Communist conspiracy, and that American democracy was in a death match with enemies within as much as without. (Goldwater was, political genealogists will note, a ferocious admirer and defender of Joe McCarthy, whose counsel in all things conspiratorial was Roy Cohn, Donald Trump’s mentor.)”

BANG! 💥 Goldwater was a less personally malevolent figure than Trump, and, yes, he lost his 1964 Presidential bid. But, in sweeping the Deep South, he set a victorious neo-Confederate pattern for the next four decades of American politics, including the so-called Reagan revolution.

Nor were his forces naïvely libertarian. At the time, Goldwater’s ghostwriter Brent Bozell spoke approvingly of Franco’s post-Fascist Spain as spiritually far superior to decadent America, much as the highbrow Trumpites talk of the Christian regimes of Putin and Orbán.

The interesting question is not what causes autocracy (not to mention the conspiratorial thinking that feeds it) but what has ever suspended it. We constantly create post-hoc explanations for the ascent of the irrational. The Weimar inflation caused the rise of Hitler, we say; the impoverishment of Tsarism caused the Bolshevik Revolution. In fact, the inflation was over in Germany long before Hitler rose, and Lenin came to power not in anything that resembled a revolution – which had happened already under the leadership of far more pluralistic politicians – but in a coup d’état by a militant minority.

Best single-volume history of the Russian revolution, highly recommended by many of my Russian friends: “A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution” by Orlando Figes. Packed with detail (1,100 pages) which is required for such a complex story.

It’s force of personality, opportunity, and sheer accident: these were much more decisive than some neat formula of suffering in, autocracy out.

In the U.S., Trump came to power not because of an overwhelming wave of popular sentiment – he lost his two elections by a cumulative ten million votes – but because of an orphaned electoral system left on our doorstep by an exhausted 18th century Constitutional Convention which left “the electoral process” sections as the last thing to do on its agenda in its last few days and they cobbled together … what exactly?!

Best single-volume history of the American Russian revolution: Alan Taylor’s book entitled American Revolutions (note the plural) about the U.S. from 1750-1804.

Back to Gopnik:

“It’s true that our diagnoses, however dubious as explanations, still point to real maladies. Certainly there are all sorts of reasons for reducing economic and social inequality. But Trump’s power was not rooted in economic interests, and his approval rating among his followers was the same when things were going well as it is now, when they’re going badly. Then, too, some of the blandest occupants of the Oval Office were lofted there during previous peaks of inequality.”

The real way to shore up American democracy? Not lovely inaugural poems. Not “let’s all feel good”. It is to REALLY shore up American democracy — that is, to strengthen liberal institutions, in ways that are unglamorously specific and discouragingly minute. The task here is not so much to “peer into our souls” as to reduce the enormous democratic deficits under which the country labors, most notably an electoral landscape in which farmland tilts to power while city blocks are flattened.

This means remedying manipulative redistricting while reforming the Electoral College and the Senate. Achievable? Nah. And even if it were, the American mindset is “we checked every box so set-it-and-forget-it” solutions. Democratic fragility would still stand. The temptation of anti-democratic cult politics is forever with us.

Because Americans just do not get it. The rule of law, the protection of rights, and the procedures of civil governance are not fixed foundations, shaken by events, but practices and habits, constantly threatened, frequently renewable. “A republic if you can keep it,” Benjamin Franklin said. Keeping a republic is a matter not of preserving it like pickles but of working it like dough — which sounds like something you’d serve alongside very weak tea.

The shifts and pivots of the American nation at large are also those of each individual American. The grand political stage and the intimate life are inseparable; identity itself is inextricable from the currents of history. Yeah. Try to “fix” that.

And what few talk about: “The War on Terror” which created a paranoid, racist and militarized atmosphere of permanent emergency. And because the war on terror has never ended, it creates a volatile atmosphere for people obsessed with American invincibility, fueling frustration that the war’s failure is due to internal subversion. When you tell people for an entire generation that their enemies are among them, some of them are going to act accordingly. America’s foreign wars have fueled waves of racist extremism at home for at least a century, including a huge resurgence of Ku Klux Klan membership in the wake of the first world war.

Historian Kathleen Belew has documented how white veterans of the Vietnam war, and non-veterans obsessed with the war’s failure, played a crucial role in violent white power movements in the 1970s through the 1990s. The deadliest domestic terror attack in recent decades, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, was carried out by a Gulf war veteran, Timothy McVeigh.

As many have written, Joe Biden is finding out what’s left of “America”. The unruliness of the nation will doom Biden’s best efforts. He has a long, uphill road ahead of him coming into the presidency. When Americans are divided on simple facts, and live in two different realities, they are not a governable people. To put it another way, when two people playing a game cannot agree on the basic rules and layout of the game, they cannot play. When groups within American society believe in two different sets of rules on how to play the game of democracy, it cannot be played and it become ungovernable.

On one hand, Biden has put in much work with his transition team on vaccination and stimulus plans. He comes into office as a man of respect and civility, who wants to bring relief to the American people. On the other hand, the country is fundamentally divided and Congressional Republicans will continue playing hardball, like they did during Obama’s presidency. The past few elections have helped to demonstrate just how difficult it is for America to overcome the longstanding racism and ethnocentrism that increasingly defines the division between the two parties. This conflict is so intense because it is an issue where most Americans believe there is a clear right and wrong and that compromise is not an option. For that reason, it is hard to see prospects for moving beyond this issue in the immediate future.

Read Harold James. He goes a step further. He warned that not only is American politics under extreme pressure, the larger social order is too — the kind of pressure that produced both national and international crises during the past two centuries:

“There are striking parallels with countries which are breaking down or on the verge of civil war — the United States in the early 1860s or Germany after 1919 or the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Coups and putsches belong to that world — think of the August 1991 coup against Gorbachev, or the multiple putsches of the early 1920s in Germany. The Soviet Union suppressed ethnic conflicts, which then broke out and pushed the society into violence, collapse and disintegration. The language and actions of the Trump presidency fanned a longtime racial divide characterized by unequal access to physical, monetary, academic and political resources.”

Over the weekend he blogged:

“Biden is the anti-Trump, with a personality that is soothing, healing, not combative. But having said that, it is the reality of the performance, in the short run on combating the pandemic, in the longer perspective on building better access to resources rather than the benign nature of the personality that will dictate the character of the legacy.”

Republicans hold the whip hand. The governability of America going forward depends in large part on whether Republican politicians return to an unequivocal adherence to democratic norms, or whether they decide to continue further down the path of Trumpism. We know. The likelihood that Republicans, or a substantial share of them, will change course is … zero.

All times seem to those within them uniquely miserable. Even supposedly halcyon historical moments were horrible if you had to live through them: the eighteen-nineties in London, which now seem a time of wit and Café Royal luxury, were mostly seen then as decadent, if you were no fan of Oscar Wilde’s, or as dark and disgraceful, if you were. The allegedly placid American nineteen-fifties were regarded, at the time, as a decade of frightening conformity and approaching apocalypse.

But this does not mean that some moments can’t be uniquely miserable. Ours surely is. I look back at America (which I left in 2005) and shake my head. It is difficult to write about it because although I am no longer a U.S. citizen I find myself irrevocably tangled in America’s hopes, arrogance, and despair. I am still “American” at heart, I suppose. But I have always spent huge chunks of time on both shores, the U.S. and Europe. I have the comfort of living and writing in a remote part of Greece, a place made of earth, air, fire and water. It breathes. Here you can get a bit nearer to the stars and the ether. And there is a blanket of stars every night.

And I am fortunate. I was born in the U.S. to Greek parents so English and Greek became “native” languages. I did one year of university at the Sorbonne (almost 40 years ago 😱) and then 15 years ago moved to Brussels (then Paris, now Greece) so added French to my quill. I find myself poised between/among three countries, two or three languages and several cultural traditions. But that is also true for a large portion of my readers.

So you would think that allows me to effectively and responsibly act in a multi-cultural world. But, no. In an age of constant shock, endless extremes and interminable nerve-jangling information inundating in real time, my nerves are numb and I am battle-hardened to it all. I am sure many of you are of the same mind. My emotions are out of whack and generally I don’t react to things like I used to. Terrorism washes over me; economic calamity is “just another of those things”; poisonously sullied political discourse gets a channel-change (or, now app-quit); disease pandemic gets a boredly indifferent yawn of “I told you so – but all those warnings fell on deaf ears.” I don’t care about most of the things that I used to.

I suppose it is all a self-defense mechanism to stop ourselves getting overwhelmed by grief, angst, horror or despair. Or better: these misplaced “hopeful” shoots when scanning political arguments in the U.S. over the past four years, wave after wave of debate, each one depositing the fine silt of clarifying distinctions – increasingly well-developed – but always well-entrenched, unmovable positions. But philosophical critiques are a waste of time, in fact they are bullshit. America shows the workings of power politics always end … if they ever do end … through the workings of brutal power politics. It is why I marvel at the insistence in so many quarters that the election of Joe Biden will erase the legacy of Donald Trump.

Americans just do not know their history, do not understand their culture. The racism, xenophobia and violence in America is so deep-seated. “Trumpian populism” should be divorced from Trump, who has ridden a political wave that he neither initiated nor controls. Its main source is anger at the advance of cultural liberalism, economic stagnation, and inequality – all of which have been blamed, with more or less justice, on national elites and the institutions they dominate. More on that history below.

“No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public.”

-H.L. Mencken, “Notes on Journalism” (1926)

What the COVID-19 crisis revealed about America (finally) was the truth we all hated to admit. That the basic structure of U.S. polities, both from a legal perspective and a real perspective, was that America is really just a federation of states, that it has never really been “United”. Even the arrival of a deadly global pandemic could not unify the nation even for a moment. Indeed, from the outset of the crisis American society polarized along the same political grooves that it has been stuck in for years, and it got worse. In fact downright feudal most of the time (more about that further below).

But Tom Skinnet, a long-time Brit friend recently wrote me that the UK is way ahead of us on the feudal front:

The United Kingdom is, as its name suggests, a feudal arrangement—not just in the metaphorical sense, but quite literally. When citizens pay taxes they pay them to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs; when they commit crimes they face the Crown Prosecution Service. Legislative power is exercised by the Queen-in-Parliament; executive power by Her Majesty’s Government; even spiritual power, in the form of the Church of England, is vested in her person. The concrete expression of this structure comes once a week, usually on Wednesdays at 6:30 p.m., when the prime minister, who serves at the Queen’s discretion, is obliged to visit Buckingham Palace to account for himself. All of this is well known and yet from a certain point of view it remains shocking. If we ask ourselves by what right one human being could hold such power over others, assuming the equal worth of all, we will not easily find an answer. The system is a historical inheritance that reflects past power struggles; there is no principle of justice that would recommend it. And yet republican arguments are hard to take seriously in the United Kingdom—they seem jejune, adolescent, the stuff of debate clubs. That is partly because our sense of what is achievable shapes our sense of what is worth getting exercised over, and in a democratic society what is achievable depends on popular opinion. But it is also because arbitrary traditions can be a resource. As human beings we need symbolic as well as material support from our leaders, and in practice the monarchy serves mostly to separate this function from executive power, which is probably a good thing. Hard to say given the current incompetent bunch in charge.

But one other thing we share with our British cousins is our frenzy over politics. Alexis de Tocqueville in his 19th century classic, Democracy in America (1835), wrote:

The election of the president is a cause of agitation, but not ruin. Nevertheless, one may consider the time of the presidential election as a moment of national crisis. The whole nation engages, gets into a feverish state, and the election is … the subject of every thought and the sole interest for the moment.”

And over the last few years when American presidential elections came around (or are they just eternally going on?) every outcome “will be pivotal for the country, if not humanity”. Jack Newburt of Slate magazine recounted the tsunami of past headlines that included : “I fear for our country if John Kerry wins” and “God has a plan for the ages. George W Bush will hold back the evil a little bit. Or we are doomed”

And maybe, just maybe, the prospect of ruin feels both real and imminent. Americans went to the polls in November amid an unprecedented range of overlapping crises: a pandemic that at the time had infected more than eight million US citizens and killed close to 230,000; an economic depression that had left more than 25 million unemployed and forced eight million into poverty since May; a racial rebellion that had sparked a violent racist backlash in various parts of the country; and environmental calamity evident in persistent wildfires.

Plus Americans were concerned about the legitimacy of the election, some serious and well-founded, others frivolous and contrived, all widespread. Poll after poll revealed almost three quarters of Americans were concerned about voter suppression or possible election interference and half of registered voters expected difficulties casting their ballot, compared to the 85 per cent who presumed it would be easy during the 2018 midterms. In California, the nation’s most populous state, more than half of voters under 30 believed the election will not be fair and open.

So we saw headlines and commentary like this: “Our democracy is in terrible danger – more danger than it has been since the Civil War, more than after Pearl Harbor, more than during the Cuban Missile Crisis and more danger than during Watergate.”

Yeah, those dangers were real, but the historical context is fictitious. America was a slave state for more than 200 hundred years; an apartheid state for a century and has only been a non-racial democracy for less than six decades. Most of the country couldn’t vote during the Civil War. Black people were not legally protected to vote during Pearl Harbor or the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Just as it is the awareness of police shooting black people has risen, not the number of shootings themselves, so the new-found awareness of the fragility of American democracy should not be mistaken for that fragility being new. Trump’s wilful violations of democratic norms are more accurately understood as a brazen, reckless and incendiary continuation of America’s long-running racist political culture than a rupture from it.

The legal, political and rhetorical groundwork for these violations had been laid long before he came on the scene. He did not create it; he is the product of it. Let’s look at some history.

The anger and hate eating America

The H.L. Mencken quote I noted above is one of the gentler quips uttered by the acerbic American journalist/writer, editor and social critic and thinker H.L. Mencken. I would posit, by the same token, that nobody ever went broke overestimating the anger of the American people. The country is in an unusually flammable mood. This being America, there are plenty of business people around to monetize the fury — to foment it, manipulate it and spin it into profits. These are the entrepreneurs of outrage and barons of bigotry who have paved the way for Donald Trump’s rise … and given him the gale-force wind to upend everything in this election season.

And it is just a logical step in a long developing history. America has laid waste to its principles of democracy as chronicled by event after event in its history.

And as a historical correction, let me note this. The Mencken “quote” (most sources who use it fail to quote it properly) is actually the traditional paraphrase of what Mencken actually wrote — not a true quote. Just as the phrase “information wants to be free” has been paraphrased and used ad infinitum, it always seems to be missing its full context (see my short piece explaining that phrase here).

Mencken used to write a column for the Chicago Daily Tribune. In his column for the September 19, 1926 edition (he titled that day’s column “Notes on Journalism”) his focus was the recent trend in the American newspaper business that came to be called “tabloid newspapers” (he coined the phrase) that were geared toward uneducated readers, including those Mencken described as “near-illiterates.” It was a drive by newspaper companies to be less substantive and intellectual than regular newspapers like the Tribune, hoping to sell to the masses.

I will skip the detailed points Mencken made on journalism, education, mass media, etc. (I am a Mencken fan; I have almost all of his writings) and give you the appropriate paragraph from the piece:

“No one in this world, so far as I know — and I have searched the records for years, and employed agents to help me — has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of the plain people. Nor has anyone ever lost public office thereby. Because the plain people are able to speak and understand, and even, in many cases, to read and write, it is assumed that they have ideas in their heads, and an appetite for more. This assumption is a folly.”

Looking around at the media and political landscape today, Mencken’s opinion might be deemed more prescient than ever. But the question today in American politics is whether the milestone we have reached is the end point … or another marker on a long road.

And for literature buffs, how about F. Scott Fitzgerald, specifically this quote from The Great Gatsby (the Tom Buchanan character speaking):

“If we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s up to us who are the dominant race to watch out or these other races will have control of things.”

I have a collection of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s letters and it’s worth noting what he says inspired the quote. The novel was written and published in 1925, but was set in the summer of 1922. Congress had just passed a law restricting overall immigration; in 1924 it passed another, targeting Catholic and Jewish “hordes” from Southern and Eastern Europe, seedbeds of anarchy and “bolshevism.” Tom Buchanan would later morph into the conservative nationalist Pat Buchanan 🙂

I want to run through just a wee bit of American history. Because all of this racism, xenophobia and violence due to Donald Trump we have seen many, many, many, many times before in U.S. history. Oh how quickly Americans forget. Yes, the usual explanation for Trump’s success, especially within “the mainstream media,” is the simple “one-two” of racism and xenophobia. But those are epithets, not even meaningful descriptions. The truth is that in the 21st century, with the end of the Cold War and the rise of the asymmetrical dangers of terrorist attack, the American public lost much of its appetite for global engagement — military, political, economic, cultural. Even if Trump loses this week — still unknown — he will not go away, his voters won’t go away and neither will the issues he raised. They will do everything in their power to make sure Biden and the Democrats fail.

This is America’s “legacy” contribution to democracy: factions and brutal power politics.

America’s fourth president, James Madison, envisaged the United States constitution as representation tempered by competition between factions. In the 10th federalist paper, written in 1787, he argued that large republics were better insulated from corruption than small, or “pure” democracies. A large electorate on a grand scale would be more likely to select people of “enlightened views and virtuous sentiments”.

But what we got was a large electorate dominated by a tiny faction. What Madison could not have foreseen was the extent to which unconstrained campaign finance, a sophisticated lobbying industry, and a media/entertainment obsessed culture would come to dominate an entire nation.

In the world as we know it, the stable “democracies” in Europe and North America have long been considered guiding examples of how government by the people can endure. That idea is now being endangered, as Donald Trump’s demagogic rise mobilizes anti-democratic threats to minorities, journalists, and the system of voting itself. His supporters are united partly by a sense of doom and persecution (some of it well founded), with the idea that their world is ending and they need to take it back.

At its very simplest, Trump has given voice to an unheard America, the have-nots. But over the last four years we have learned Trump means many different things to his supporters, but all of them feel ignored by Washington. They hear of the glory of globalization from the world’s have-a-lots, but you know what? All this bullshit “prosperity” was never properly shared.

Most amusing (if that is the appropriate word), is that the racism, xenophobia and violence of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign is widely seen as an aberration, as if reasoned debate had been the default mode of American politics. But most have forgotten their U.S. history (or simply never read it) because precursors to Trump do exist, candidates who struck electoral gold by appealing to exaggerated fears, real grievances and visceral prejudices.

Does nobody remember the anti-immigrant “Know-Nothing” party of the 1850s? Or the white supremacist politicians of the Jim Crow era? Or the more recent hucksters and demagogues including Joe McCarthy and George Wallace? How about more respectable types such as Richard Nixon, whose “Southern strategy” offered a blueprint for mobilizing white resentment over the gains of the Civil Rights movement?

I know, I know, I know: that “respectable” and “Nixon” can be included in the same sentence illustrates how far my political standards have evolved since the 1970s.

And sketchy things said about races and genders and groups and opponents and other outrageous acts in the past? It wasn’t Trump who read Dr. Seuss to filibuster congress in a routine budget function. It wasn’t Trump who lied about weapons of mass destruction. It was not Trump who used Willie Horton, or Trump who swift-boated a decorated war hero.

Trump is not the “new” anomaly that changes the paradigm, but, rather he is just the logical outgrowth of years and years of blatant lies and surreal fabrication and contradictions. Trump merely took it up a notch, an opportunistic predator who saw that there was no downside to lying, slandering or obstructing government and he took it from there. We have seen him before. And to understand how the Republicans have been on this road for a very, very, very long time read Lewis Lapham’s analysis “Tentacles of Rage” from 2004 (click here).

Violence is not unknown in American political history. Even in colonial times leaders of the resistance to British measures and leaders for the continuance of British rule did not only rely on abstract arguments about taxation and representation but also relied on extra-legal committees and violent mobs; opponents were tarred and feathered. They each terrorized their critics.

And well into the 20th century, Southern blacks who wanted to exercise the right to vote faced violent retribution from the Ku Klux Klan and kindred groups. Let’s get over it: racism, violence, scurrilous attacks on opponents, etc. were part of American political culture from the outset.

Alas, the trope of a glorious American Revolution has worked its way into historical scholarship and brainwashed us in our youthful educations: the idea that unlike the “bad” French and Russian Revolutions which degenerated into violent class conflict, we were a “united” American people who rebelled against British overlords with restraint and decorum.

Oh, brother. For those of us who attended American university and took various American history courses, we were brainwashed by the works of Bernard Bailyn, Edmund Morgan and Gordon Wood. Air brushed out/filtered out were the enormous economic and class conflicts dividing colonial America, and the diverse often violent difference in political beliefs. As John Adams famously wrote when describing the First Continental Congress convened in 1774: “Delegates were strangers, unfamiliar with each other’s ideas and experiences and diversity of opinion”. There was no unity of political beliefs.

So let’s forget Bailyn, Morgan and Wood. We should have been reading Eric Foner, Alan Taylor, Daniel Vickers and Ian Williams. As they have written, the political ideology motivating the colonists had deep and complex roots, with deep social and class conflicts. And it was “many beliefs” that served as the primary motivation for revolution … for many different reasons.

I know. We are all pressed for time. But if you really wants get into this stuff I urge you to read the compendiums of the letters and diaries of John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, plus Alan Taylor’s book entitled American Revolutions (note the plural) about the U.S. from 1750-1804.

From all that I have read, and from the many conversations I have had with family, friends and colleagues, I feel it all boils down to this: Trump voters are not defined by their experience of economic hardship, but by their willingness to embrace a particular explanation of that hardship — namely, that it was visited upon them by a black president in cahoots with the swarthy liberal people who have taken their jobs, their “lifestyle,” and their status.

When I was in Chicago during the 2016 elections, I met up with Gabe Zeptum, a sociologist who studied the rise of the Tea Party, explained it as people who saw themselves betrayed by “line-cutters” — black people, immigrants, women and gays — who jumped ahead of them in the queue for the American dream. Southerners feel patronized and humiliated by northerners who tell them whom to feel sorry for, then dismiss them as bigots when they do not. They feel they are victims of stagnant wages and affirmative action but without the language of victimhood: struggling Southerners are not “poor-me’s”. They believe that they are honorable people in a world where traditional sources of honor — faith, independence and endurance — seem to go unrecognized. Well, until Donald Trump began offering hope and emotional affirmation.

The clincher for me was at a Trump rally that summer that Zeptum managed to get me into. I met one chap … one of the few literate in the bunch … who talked about the “Trump Train”. He talked about Trump’s “track record of success over the last four years” (I was not there to argue) and he admitted “yes, he has a foul mouth and talks like a sailor and I will never agree with him on everything”.

But then the money shot:

“The thing is nobody has been able to fix my problem and this man tells me that he can. And he has. Look at the four years of success. I believe him and I am going to rehire him to do the job. We Donald Trump supporters don’t agree with everything that he has done in the past and we all wish that he would make it easier for us to stand up and fight for him but the Trump Train continues to grow and grow and grow.”

It’s why I also think this thing gets wrongly played on so many fields. Over the last weeks of the 2020 elections I watched CNN’s Latin American version (oh the benefits of satellite TV), listening to Latinos being interviewed, openly supporting Trump. Nearly all because they say they have done well economically over the last 4 years. So no surprise when it was revealed Trump did surprisingly well with that group, and gave him Florida.

The problem is so basic and people need to learn this, especially Democrats. People will ALWAYS vote in their own (perceived) best interests, not the best interests of the community. Democrat policies are always more community focused, but most American voters don’t care. It’s about me me me. Trump fed this narrative.

Yes, you’d think the human mind in 2020 … with all that technology … should be far more resilient against racist, bigamist, facist hate speech spewing from the mouth of Trump. It’s hard to defend such contempt and juvenile behavior. But the average American voter does not care. I always tell my Democrat, liberal friends “You must be exhausted by wishing and hoping your fellow citizens would just be decent and rational.”

Yep. Forget automation. Forget globalization. Forget decades of Republican fiscal policy that starved the nation of infrastructure and human capital while directing the benefits of economic growth to the already engorged rich. Forget personal choices to forgo higher education and additional training. Forget the fact that the ability of low- and semi-skilled workers to achieve a middle-class life was an artifact of a particular moment in this nation’s economic history.

Oh, in case you forgot, remember this: that damn Barack Obama, that black man, was president when our moment was definitively over, when “our train left the station”. And he WANTED it that way.

For people who loathe Trump, such steadfast loyalty is hard to fathom. And to add a kicker, a colleague with whom I work in the Middle East on war crime investigations said “we have reached a new milestone. For the first time in history, it is easier to understand the politics of the Middle East than the politics of America”.

Trump’s strength, as explained by so many pundits, was due to his strength and extraordinary popularity with these people. Trump is an opioid for the masses. What Trump offers is an easy escape from the pain. His promises are the needle in America’s collective vein.Trump is cultural heroin. He makes some feel better for a bit. But he cannot fix what ails them, and one day they’ll realize it.

Democracy is for the Gods, not humans

My mother told me to be polite to strangers as a matter of self-respect and also because they may be enduring some personal tragedy you will never be aware of, so be kind. Civility is based on empathy, and it is at the heart of democracy. But civility is dead in America, and it shall never come back. And so democracy is dead. America must turn the page on that bit of its history. But was it ever (really) a democracy?

There has been a flood of books over the past few years on the theme “Why do democracies fail?”. Well, books, and opinion pages and cable news shows, in an increasingly anxious public debate. But I always find myself answering the question with another question: “Why shouldn’t they fail?” Because in the short history of mankind on this planet, every democracy, every republic has failed. And history is the only true guide we have on this matter. We know that democracy is rare and fleeting. It flares up almost mysteriously in some fortunate place or another, and then fades out, it seems, just as mysteriously. Genuine democracy is difficult to achieve and once achieved, fragile. In the grand scheme of human events, it is the exception, not the rule. As Paul Woodruff put it in his 2006 book “First Democracy: The Challenge of an Ancient Idea” :

Democracy – all adults are free to chime in, to join the conversation on how they should arrange their life together. Despite democracy’s elusive nature, its core idea is disarmingly simple: as members of a community, we should have an equal say in how we conduct our life together. And no one is left free to enjoy the unchecked power that leads to arrogance and abuse. Have you ever heard of anything more reasonable?

Hold on. Whoever said we were a reasonable species? Fundamentally, humans are not predisposed to living democratically. One can even make the point that democracy is “unnatural” because it goes against our vital instincts and impulses. What’s most natural to us, just as to any living creature, is to seek to survive and reproduce. And for that purpose, we assert ourselves — relentlessly, unwittingly, savagely, violently — against others. We push them aside, overstep them, overthrow them, even crush them if necessary. Behind the smiling facade of human civilization, there is at work the same blind drive toward self-assertion that we find in the animal realm. Just scratch the surface of the human community and soon you will find the horde. As zoologist Konrad Lorenz writes in his book “On Aggression” :

It is the unreasoning and unreasonable human nature that pushes two political parties or religions with amazingly similar programs of salvation to fight each other bitterly, just as it compels an Alexander or a Napoleon to sacrifice millions of lives in his attempt to unite the world under his scepter. World history, for the most part, is the story of excessively self-assertive individuals in search of various scepters.

It doesn’t help matters that, once such an individual has been enthroned, others are only too eager to submit to him. It is as though, in his illustrious presence, they realize they have too much freedom on their hands, which they find suddenly oppressive. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Hitler and Mussolini were all smooth talkers, charmers of crowds and great political seducers. So are Donald Trump and Boris Johnson.

Their relationship with the crowd is particularly intimate. For in regimes of this kind, whenever power is used and displayed, the effect is profoundly erotic. Just watch a Trump rally. Better yet, watch “The Triumph of the Will” (thanks, in good measure, to Leni Riefenstahl’s perverse genius) to see people experiencing a sort of collective ecstasy. The seducer’s pronouncements may be empty, even nonsensical, but that matters little; each one brings the aroused crowd to new heights of pleasure. He can do whatever he likes with the enraptured followers now. They will submit to any of their master’s fancies.

This is, roughly, the human context against which the democratic idea emerges. No wonder that it is a losing battle. Genuine democracy doesn’t make grand promises, does not seduce or charm, but only aspires to a certain measure of human dignity. It is not erotic. Compared to what happens in populist regimes, it is a pretty frigid affair.

And in today’s Instagram world? Boooooring! Who in his right mind would choose the dull responsibilities of democracy over the instant gratification a demagogue will provide? Frigidity over boundless ecstasy? Boundless emotion? Boundless feelings, none of that “mental stuff”? And yet, despite all this, the democratic idea has come close to embodiment a few times in history — moments of grace when humanity almost managed to surprise itself.

Costica Bradatan is an American philosopher, a Professor of Humanities in the Honors College at Texas Tech University. He has a book-in-progress, some of which he has shared in series of essays in various magazine and journals. In one essay he noted:

One element that is needed for democracy to emerge is a sense of humility. A humility at once collective and internalized, penetrating, even visionary, yet true. That has been completely lost in Amercia.

The kind of humility means being comfortable in your own skin, because you know your worth, your limits, and can even laugh at itself. A humility that, having seen many a crazy thing and learned to tolerate them, has become wise and patient. To be a true democrat, in other words, is to understand that when it comes to the business of living together, you are no better than the others, and to act accordingly. That has been erased in America. The institutions of democracy, all of its norms and mechanisms, have been corrupted.

Ancient Athenian democracy devised several institutions that fleshed out this vision and it made democracy work – for awhile. One of them was the institution of ostracization. When one of the citizens was becoming a bit too popular — too much of a charmer — Athenians would vote him out of the city for ten years by inscribing his name on bits of pottery. It was not punishment for something the charmer may have done, but a pre-emptive measure against what he might do if left unchecked. Athenians knew that they were too vulnerable and too flawed to resist political seduction so they promptly denied themselves the pleasure. IF Stone in his classic book The Trial of Socrates fleshes this out in detail having done a dive into scores of ancient texts. But the gist is: “Man-made as it is, democracy is fragile and of a weak constitution — better not to put it to the test. There are so many ways it can crumble.”

Yes, democracy has resurfaced elsewhere, but in forms that the ancient Athenians would probably have trouble calling “democratic”. For instance, much of today’s American democracy would by Athenian standards be judged “oligarchic” although I think “kleptocracy” is the better word. It’s the fortunate wealthy few (hoi oligoi) who typically decide here not only the rules of the political game, but also who wins and who loses. Ironically, the system favors what we desperately wanted to avoid when we opted for democracy in the first place: the power-hungry, arrogant, oppressively self-assertive political animal. Funny, that.

Yet we should not be surprised. It was Jean-Jacques Rousseau who wrote:

So perfect a form of government as democracy is not for men. If there were a people of gods, it would govern itself democratically. But not a people of men.

Democracy is so hard to find in the human world that most of the time when we speak of it, we refer to a remote ideal rather than a fact. That’s what democracy is ultimately about: an ideal that people attempt to put into practice from time to time. Never adequately and never for long — always clumsily, timidly, as though for a trial period.

Postscript: the American future

Perhaps I am indulgent to the past, or I am always looking for patterns. But I do look to the rhythm of history, at what is conspicuous. We tend to learn history and our world in pieces. This is partly because we often have only pieces of the past (shards, ostraca, palimpsests, crumbling codices with missing pages) and even the present (news clips, Twitter/Facebook/”name-that-snip” barrages).

I think you need to take a break from the deafening cacophony of daily noise and take the pieces and set them next to one another, examine, contrast and compare, and attain an overview. And I realize most of the people reading this do not have the amount of time I do. As one of my readers noted: “Look, we are all pretty much just commerce monkeys, commerce machines. We barely have enough time to read and write and produce for our jobs. Who the hell has time for a big think?!”

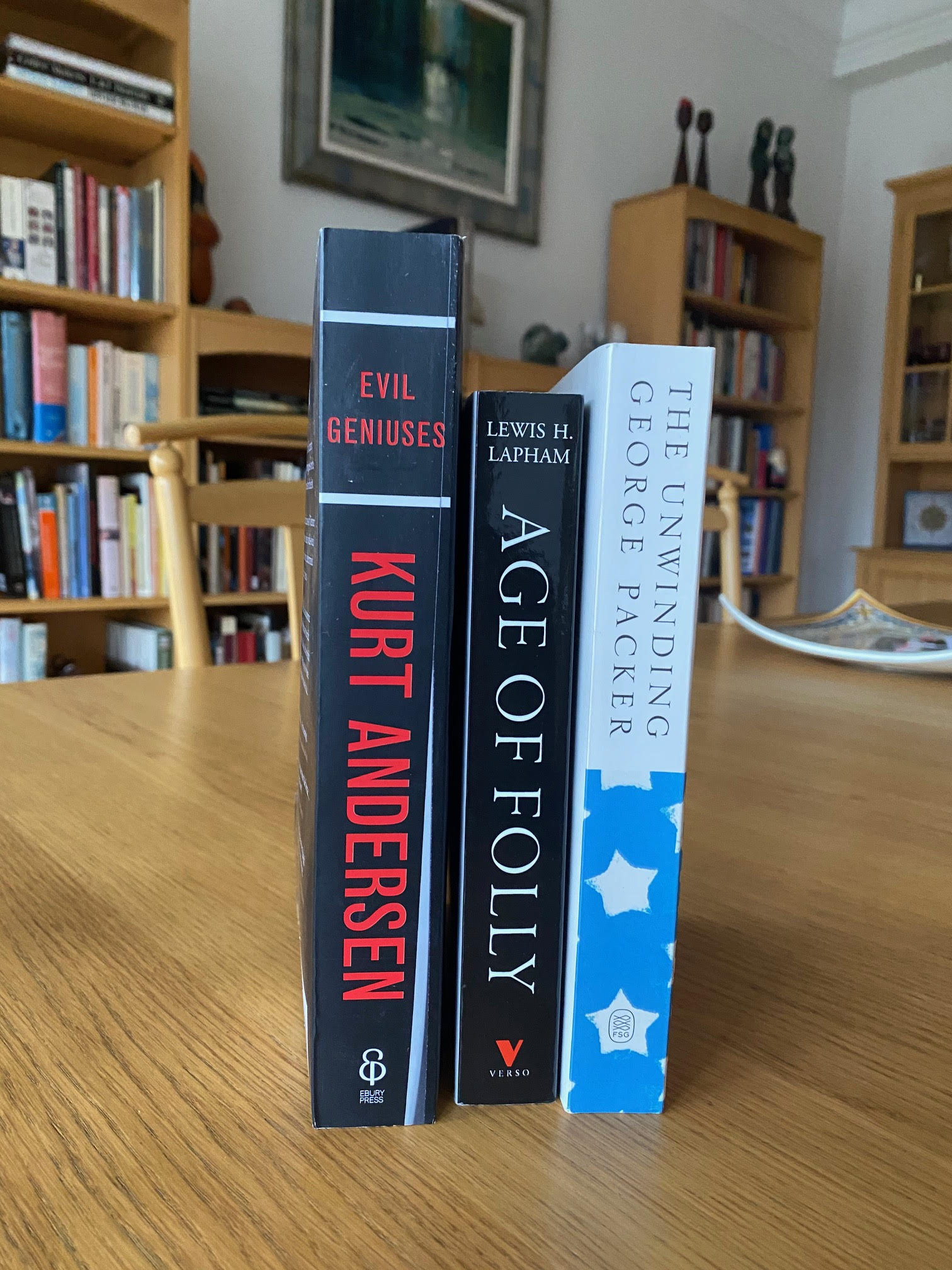

I have slung a lot of book references at you in this piece. More will come in the final piece. But if you have the time I shall recommend only three books:

George Packer’s The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America, published in 2013, traces the disintegration of American society and its eventual massive polarization – laying out how this disintegration has been going on for a long time but had not triggered any sense of crisis. But it would come.

Kurt Anderson’s Evil Geniuses is a catalog of American sociopolitical history – a brilliant deep dive into America’s paradoxical legacy of innovation and ego and “freedom” and how its alleged “egalitarian ideals” were turned into its present course of social and moral catastrophy.

Lewis Lapham in Age of Folly, published in 2016 but updated in 2020 for “the Age of Trump”, chronicles American democracy degrading into plutocracy for the past 23+ years. It was “gradual” he says.

Ah, gradual. Remember that passage in Ernest Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises in which a character named Mike is asked how he went bankrupt? “Two ways,” he answers. “Gradually, then suddenly.” Technological change happens much the same way. As does political change. Small changes accumulate, and suddenly the world is a different place. We’ve all tracked (and some of us have been involved with) “gradually, then suddenly” movements: the World Wide Web, open source software, big data, cloud computing, sensors and ubiquitous computing, and now the pervasive effects of AI and algorithmic systems on society and the economy.

But social media technology has transformed politics and society irrevocably, in a dystopian way, that we are only now slowly grasping. Our civil institutions were founded upon an assumption that people would be able to agree on what reality is, agree on facts, and that they would then make rational, good-faith decisions based on that. They might disagree as to how to interpret those facts or what their political philosophy was, but it was all founded on a shared understanding of reality. And that’s now been dissolved out from under us, and we don’t have a mechanism to address that problem.

And that is the most amusing part of all of this: people act as if the structure of politics has not changed. It is now an argument that will never be over, never be fully won. But for most of us it is hard to argue well, or at all, without cleaving to the fantasy that if we just argue well enough, we can cheat disagreement. We need to believe our arguments will work, that our opponent will – or at the very least could – succumb to the unforced force of our words. To endure arguing at all, we need the fantasy that the arguing will, one day, be over.

It will grow worse. The dissemination of the written word, from the time of Gutenberg, has enabled us to tell stories of great depth and complexity, and to share our analyses of these stories. I don’t just mean literature: history, too, is the analysis of human stories; as are psychology, anthropology, law, and philosophy. The dramatic prevalence of the image over the written word in our present moment is akin to a return to the Lascaux caves: immediacy has its advantages, but nuance isn’t one of them.

It is also why of late I advocate for the actual, irreducible, and irreplaceable animal record – outside the age of mechanical reproduction. This entire post was hand-written, edited, crossed-out, cut, pasted … then typed and graphically-amended by my team.

The movement of the hand that holds the pen; the imprint of ink upon paper; the dignity and intimacy of the individual essay – so different from a blog or social-media post), without thought of other readers. You need to write for yourself. The loss of what that represents philosophically is enormous: my grandparents, my parents, even some of my friends and I in our youth, spent hours writing letters and essays about what we were doing and thinking, where we were going and what we noticed, as a gesture of intimate communication. Depth and richness of thought.

All of this is important today especially with the current conversations over gutting Section 230 of the U.S. Communications Decency Act of 1996 which provides immunity for website publishers from third-party content. Plus the barrage of commentary on the need for social media content moderation.

But it is too late. We’ve moved beyond that. Yes, Biden won. But radicalism will spread, mutating into new forms. America is deeply enmeshed in a death spiral which has been described, in other times and places, as “cumulative extremism“. And “content moderation”? Look, for example, at what QAnon adherents are doing: they moved to Gab, then Parler (ok, got kicked off), plus Telegram and many smaller platforms after being removed from Facebook and YouTube. And they setting up “subscription only” web sites. The horse has left the barn. Galloped out, actually. Those moves show that conspiracy movements can continue to gain traction even after losing access to the largest platforms.

Because the “how” of social organizing matters more and that’s because the means of connectivity impacts the nature of a movement, the chance for its success, the tactics it can adopt – which in turn, impact its character – and the roles in can play, and the measures the state can deploy against it. All of these shape the nature, outlook and the reach of the movement.

One can only imagine the militia members, armed groups, and other Trump supporters armed at the polls on Tuesday hoping to create more chaotic moments.

I agree with Packer: we will “suddenly” find our society attacked and disrupted and we will “both remember and forget the accumulated mass of history burning that caused the present fire”. As he says, in American society, we are witnessing an “unwinding,” where the institutions that gave structure and meaning to collective life will slowly collapse “like pillars of salt across the vast visible landscape.”

I will admit I am a media guy. I do enjoy the latest/newest revolutions in information technology, offering a previously unimaginable kaleidoscope of information …. an infinite, infinitely multiplying space. But my God can it fracture attention. And the data can and will bewilder, the web churning out articles and videos and images at a rapid-fire pace, adding new details to the news every few minutes. Blogs, Facebook feeds, Tumblr accounts, Tweets, and propaganda outlets repurpose, borrow, and add topspin to the same output.

Trump learned to steeple-chase all those checks-and-balances that have unhorsed predecessors with far more experience and aplomb than he possesses. He found out that all that stuff was “voluntary” so long as you controlled the organs of power and had buckets of enablers.

The truth of the matter is the US’s electoral system was already violating “democratic” norms in ways that almost certainly determined the outcome of elections, including the one that gave us Trump. Forget the Electoral College. Just look at gerrymandering. Chris Lester of The Freedom Project sent me this:

Ok, gerrymandering. A longstanding practice whereby both political parties carve up constituencies in order to maximise their chances of winning the most seats by corralling as many of their opponents’ voters in one seat, leaving the rest for themselves. But let’s just look at Wisconsin. In 2012 Republicans received 46 per cent of the popular vote in Wisconsin state elections but they received 60 per cent of the seats in the state assembly. Nationwide that year Democrats got 1.4 million more votes in House races. Republicans won 33 more seats. That’s “democracy”?

My old editor, John Lindell, always told me “in almost every book I have read (other than the ones I edited), I feel like chopping off the last paragraph. The author makes profound, definitive, often controversial statements throughout his work and then ends in a Caspar Milquetoast-like paragraph”. John, in your memory, I shall conclude forcefully as follows:

This was the strangest election in modern American history, seeming to yield no consensus whatsoever. The U.S. came as close to suicide as it did during the Civil War.

But the events of 6 January linger. Trump continues to stir emotions which have long lurked below America’s cultural surface. The challenge with Trump has long been to distinguish what is truly aberrant from what is a crude and flamboyant continuum of that which came before. Racism, xenophobia, misogyny, lying or conspiracy theories in politics – up to and including at its highest level – long preceded him. But he exploited and articulated them in a more forthright manner than any of his predecessors and in ways that are substantial and consequential.

And that is the most amusing (if that is the appropriate word) bit: that the racism, xenophobia and violence of Donald Trump’s presidential campaigns and presidency were widely seen as an “aberration”, as if reasoned debate had been the default mode of American politics. But most have forgotten their U.S. history (or simply never read it) because precursors to Trump do exist, candidates who struck electoral gold by appealing to exaggerated fears, real grievances and visceral prejudices.

Does nobody remember the anti-immigrant “Know-Nothing” party of the 1850s? Or the white supremacist politicians of the Jim Crow era? Or the more recent hucksters and demagogues including Joe McCarthy and George Wallace? How about more respectable types such as Richard Nixon, whose “Southern strategy” offered a blueprint for mobilizing white resentment over the gains of the Civil Rights movement?

I know, I know, I know: that “respectable” and “Nixon” can be included in the same sentence illustrates how far my political standards have evolved since the 1970s.

And sketchy things said about races and genders and groups and opponents and other outrageous acts in the past? It wasn’t Trump who read Dr. Seuss to filibuster congress in a routine budget function. It wasn’t Trump who lied about weapons of mass destruction. It was not Trump who used Willie Horton, or Trump who swift-boated a decorated war hero.

Trump is not the “new” anomaly that changes the paradigm, but, rather he is just the logical outgrowth of years and years of blatant lies and surreal fabrication and contradictions. Trump merely took it up a notch, an opportunistic predator who saw that there was no downside to lying, slandering or obstructing government and he took it from there. We have seen him before.

Violence is not unknown in American political history. Even in colonial times leaders of the resistance to British measures and leaders for the continuance of British rule did not only rely on abstract arguments about taxation and representation but also relied on extra-legal committees and violent mobs; opponents were tarred and feathered. They each terrorized their critics.

And well into the 20th century, Southern blacks who wanted to exercise the right to vote faced violent retribution from the Ku Klux Klan and kindred groups. Let’s get over it: racism, violence, scurrilous attacks on opponents, etc. were part of American political culture from the outset.

Alas, the trope of a glorious American Revolution has worked its way into historical scholarship and brainwashed us in our youthful educations: the idea that unlike the “bad” French and Russian Revolutions which degenerated into violent class conflict, we were a “united” American people who rebelled against British overlords with restraint and decorum.

Oh, brother. For those of us who attended American university and took various American history courses, we were brainwashed by the works of Bernard Bailyn, Edmund Morgan and Gordon Wood. Air brushed out/filtered out were the enormous economic and class conflicts dividing colonial America, and the diverse often violent difference in political beliefs. As John Adams famously wrote when describing the First Continental Congress convened in 1774: “Delegates were strangers, unfamiliar with each other’s ideas and experiences and diversity of opinion”. There was no unity of political beliefs.

So let’s forget Bailyn, Morgan and Wood. We should have been reading Eric Foner, Alan Taylor, Daniel Vickers and Ian Williams. As they have written, the political ideology motivating the colonists had deep and complex roots, with deep social and class conflicts. And it was “many beliefs” that served as the primary motivation for revolution … for many different reasons.

The march of technology has worsened it. Those “enduring” American voices of reason, compassion, tolerance, liberty, free enterprise, courage, strength and hope are now proven what they were all the time … gloss … having been drowned out by the voices of hate. And the media willingly obliged. They really “gave us” Donald Trump. Because over the last 20+ years we moved from candidates with “vision” and “issues” to product placements, meant to be seen instead of heard, their quality to be inferred from the cost of their manufacture. And then to Trump with his bombs bursting in air? Every candidate is now, literally, a game-show contestant.

We built a commercial and technology oligarchy … paying for both the politicians and the press coverage … to treat “democracy” as if it was a talk show guest sitting alone in the green room with a bottle of water and a banana, armed with press clippings of its “once-upon-a-time-I-was-a-star” with it press clippings to prove it, waiting to come on between the shampoo commercial and the demagogue?

All of these emotions will not go away. They will get more ugly. Only the naïve still believe that significant, positive changes are afoot. What Trump and his sycophants have unleashed cannot be put back in the bottle. Only the naïve still believe it can be reversed.

For the past 200 to 300 years, ideas have been in full flow, stimulated by ever-increasing contacts between peoples, and transmitted by accelerating means of communication. Globalization is the result: a fizzing ferment of words and images. But that accelerating means of communication has caused a retreat into populism and chauvinism. Confused by chaos, infantilized by ignorance, refugees from complexity flee to fanaticism and dogma. People are being fractionated into their own information realities. The pillars of logic, truth, and reality are being replaced with fantasy, rage, and fear.

People’s cognitive architectures are being changed, and not for the better. That . will . not . change.